Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

A land of vast tundra, rugged boreal forests, and stunning Arctic islands, the Northwest Territories is the second largest of the northern territories of Canada and the most populous with about 45,000 inhabitants. There are a total of 451 mountains spread across the territory, the tallest of which is Mount Nirvana at 2,773 m (9,095 ft) in elevation.

Covering an area of 1,346,000 square kilometers (441,700 square miles), the Northwest Territories accounts for over 13 percent of Canada’s total land area. Nunavut, which is located to the east of the Northwest Territories, is the largest territory in the country as it accounts for 21 percent of Canada’s total land area.

Canada is made of 10 provinces and three territories. The main reason for the difference is the constitutional power each holds. Provinces are constitutionally independent of the federal government, while territories are delegated power from the federal government.

The difference in independence is because even though the territories are 40% of Canada’s land, they only have 3% of the population. The federal government intervenes so that territory residents can receive comparable levels of service with similar taxation levels as the provinces.

The three territories are currently Yukon in the west, Northwest Territories in the middle, and Nunavut in the east. Alberta and Saskatchewan border the Northwest Territories to the south. Northwest Territories may also share a quadripoint with Manitoba; however, since this geographic point is so remote, it has never been officially surveyed to find out.

When Canada was formed in 1867, the area originally called the North-Western Territory, consisted of most of what is now Manitoba, all of Saskatchewan and Alberta, all of the northern reaches of Canada, and large parts of both modern-day Ontario and Quebec.

Manitoba was carved out of the territory in 1871, with Alberta and Saskatchewan both being designated in 1905. Yukon was established in 1898 and Nunavut was created in 1999. Parts were also portioned off to Ontario and Quebec through several secessions giving the Northwest Territories the shape it has today.

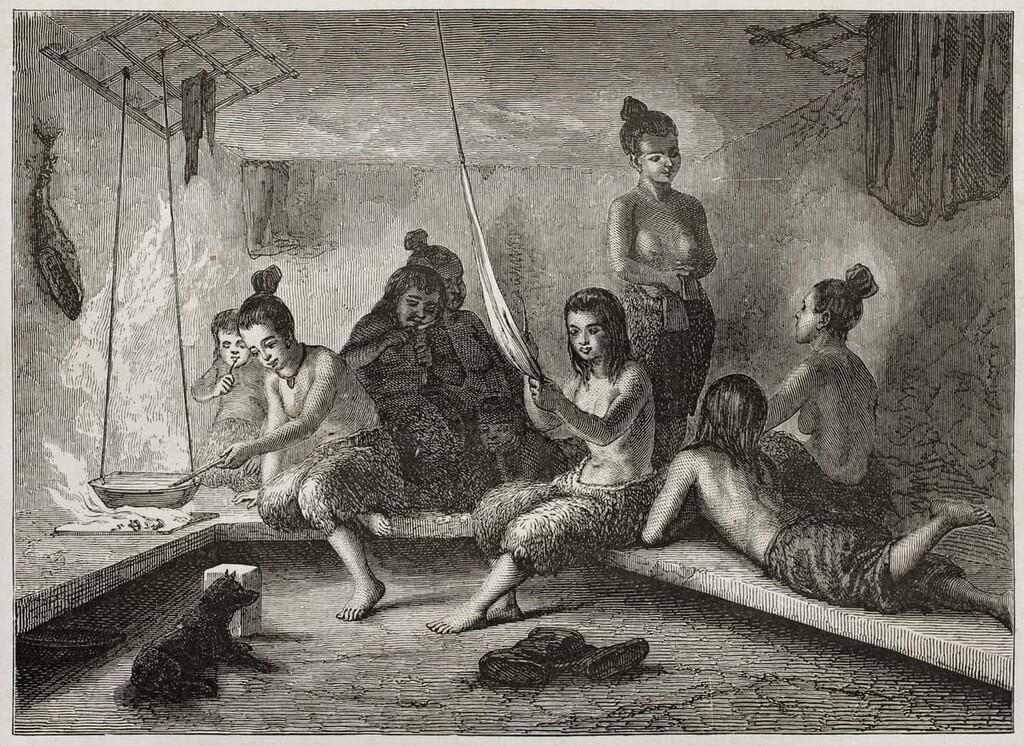

The northern half of the territory is traditionally inhabited by the Inuvialuit who call their ancestral homelands Nunatsiaq, meaning “beautiful land.” The southern half of the region is traditionally inhabited by Dene Nation who refer to their land as Denendeh, meaning “The Land of the People.”

There are five administrative regions used to classify areas of the Northwest Territories: South Slave, North Slave, Dehcho, Sahtu, Western Arctic, and Yellowknife.

The South Slave Region is considered to be the gateway to the territory. It extends from the Alberta border in the south all the way to Great Slave Lake (Tıdeè/Tinde’e/Tu Nedhé/Tucho). This area is the ancestral homelands of the Cree, Chipewyan (Dënesųłı̨ne), and Métis, among others.

The region shares many topographical similarities to northern Alberta, such as the seemingly endless boreal forest, raging rivers, and limestone chasms. It also contains part of Wood Buffalo National Park.

Located to the north of Great Slave Lake, the North Slave Region is rich in natural resources like diamonds and gold, and is where some of the oldest rock in the world is found. At an estimated 4 billion years old, the Acasta Gneiss found in this region is one of the oldest known parts of Earth’s crust.

This region is a rugged mix of stone and water where shield-rock, lakes, and rivers create a mosaic. From south the north the forests dwindle to nothing, where the tundra barrenlands begin. This is the ancestral homelands of the Tłı̨chǫ, the largest First Nation in the Northwest Territories.

Furthermore, the North Slave Region contains the territorial capital of Yellowknife. Referred to as the "little big city", Yellowknife, was established in the wake of a gold discovery in the region in 1934. However, the region around the city has been inhabited since time immemorial.

Interestingly, the name Yellowknife, has nothing to do with gold, but refers to the Yellowknives Dene First Nation people who were called such for their copper blades. These days, with 20,000 inhabitants, Yellowknife is a bustling place and the main commercial hub of the territory.

Big rivers and big mountains define Dehcho, which encompasses much of the southwestern part of the territory. The big mountains of Delcho are located in the southwestern part of the territory, which is home to Nahanni National Park Reserve, an incredible adventure destination.

Meanwhile, the big rivers of Dehcho are the Liard River and the famous Mackenzie River. The region is the ancestral homelands of the Dehcho First Nations whose ancestors have lived in the region since time immemorial.

The Sahtu Region is located at the core of the Northwest Territories. It features trackless expanses and is considered to be quite remote, even by northern standards. Despite the oil and gas that has flowed from Norman Wells for over a century, the region is still rugged and gorgeous.

The region is home to Great Bear Lake (Sahtú), Canada’s largest lake; the mile-wide Mackenzie River; and the Mackenzie Mountains. Much of the region is collectively owned by the Sahtu First Nations and the Métis of Norman Wells

The Inuvik Region is where your imagination takes you when you think of the north. Here, polar bears, reindeer, and muskox roam the tundra, ice, and mountains.

The region surrounds the Mackenzie delta where the river meets the Arctic Ocean, creating a rich environment for birds and plants. The Northwest Passage winds through the northern islands of the region that extend into the Beaufort Sea, as they reach for the pole.

This is the ancestral homelands of the Gwich'in and Inuvialuit, some of the northernmost peoples of what is now called North America.

The geology of the Northwest Territories is varied and complex. The variety of geologic events in the region’s past has created vast mineral and oil deposits that extend throughout the territory. Diamonds, gold, lead, zinc, copper, iron ore, oil, and natural gas are all found in relative abundance in the territory when compared to the rest of Canada.

The oldest rocks in the Northwest Territories are found in the Taiga Shield region, which is located east of the Mackenzie Mountains along the territory’s border with Yukon. The bedrock in this region is Precambrian sedimentary, granitic, and volcanic rock, much of which is exposed or only covered with a thin veneer of glacial till.

The bedrock here is up to 4 billion years old and the outcroppings of Acasta Gneiss, near the Acasta River, are among the oldest exposed rocks in the world. The Acasta Gneiss allows scientists to go back in history to study the formation of Earth’s crust.

As one heads northeast from the Taiga Shield, the bedrock layers are generally younger in age. The Southern Arctic generally has Cambrian period sediment bedrock, while the northern islands are Devonian to Cretaceous sandstone, siltstone, and shale. One anomaly, which accounts for some of the peaks, is a wide band of limestone and dolomite which runs through Melville Island.

The bedrock is generally very close to the surface throughout the territory, and where it is not exposed, there is usually only a thin veneer of glacial till covering it. Glaciation was widespread during the Paleozoic and glaciers only retreated from the region 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

The terrain and topography of the Northwest Territories is heavily influenced by glaciation. The glaciers moved massive amounts of rock over the course of some thousands of kilometers, depositing glacial till across the landscape. Some glacial erratics in the territory are suspected to have been displaced from the Canadian Shield by the Laurentide ice sheet during the Pleistocene. There are extensive fields of till drumlins, and the incredibly long eskers are evidence of glaciation in the region.

Other glacial and periglacial features in the Northwest Territories include thermokarst, which are sinkholes created by differential melting of the permafrost. Thermokarst are usually circular depressions that will fill with water. The other features are the ice-cored till, such as moraines and drumlins.

The mountains of the cordillera are dominated by the Mackenzie Mountains, Selwyn Mountains, and Franklin Mountains. The rocks in this area are Precambrian to Mesozoic in age. They formed as bands of sediment over the course of hundreds of millions of years, though they also feature numerous volcanic intrusions.

Layers of limestone, dolomite, sandstone, quartzite, siltstone, shale, and slate formed in the region at this time. The thickness and composition of the layers varied over the millennia based on the flow and erosional rates of the region’s glaciers and rivers.

The cordillera formed during the end of the Laramide orogeny, around 50 million years ago. The Laramide orogeny, which was also responsible for the formation of the Rocky Mountains, was a period of mountain building that occurred as the North America collided with Pacific tectonic plates. This collision caused the ancient coast of North America to uplift and form the Rocky Mountains, as well as the Northwest Territories cordillera.

The cordillera appears to be part of the Rocky Mountains; however, the Rockies official northern terminus is at the Liard River. The mountain ranges to the north are often just referred to as the Mackenzie Mountains, despite the fact that they are actually a collection of distinct ranges.

During the Mesozoic, magma slowly intruded upward through layers of sedimentary rock, creating large domes of igneous rock. The erosion-resistant igneous intrusions are surrounded by halos of metamorphosed sedimentary rock which can be many kilometers wide. Pleistocene glaciation eroded the layers of sedimentary rock, leaving behind spectacular granite spires.

While the Rocky Mountains in the United States are famous for their big granite walls, such as Half Dome and El Capitan, granite is fairly rare in Canada. There are only three locations where igneous intrusions created granite spires and walls: Bugaboo Provincial Park in British Columbia, Nahanni National Park Reserve in the Northwest Territories, and the Arctic Cordillera on the islands of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

The Innuitian Mountains are the northern ranges of the Arctic Cordillera. The mountains consist of the British Empire Range, the Princess Margaret Range, the United States Range, and the Challenger Mountains, the latter of which is often considered to be the world's northernmost mountain range.

During the Cambrian, sediments accumulated in a shallow sea north of what is now the continent of North America. Deformation of the sedimentary layers may have begun as early as the Devonian; however, the major mountain formation event of the Innuitian Mountains is considered to be the Innuitian orogeny of the middle Mesozoic.

During the Mesozoic, North America began to drift north to collide with the tectonic plates in the Arctic. The sedimentary layers were squeezed as the plates came together and began to rise and form the Innuitian Mountains. Igneous intrusions occurred throughout the range to create incredible granite walls across the remote arctic mountains.

Due to the fact that it covers some 13 percent of Canada that stretches from the sub-Arctic to the Arctic, the Northwest Territories are home to an abundance of different ecoregions. In fact, the territory is divided into five general ecoregions. The major ecoregions of the Northwest Territories are the Taiga Plains, the Taiga Shield, the Cordillera, the Southern Arctic, and the Northern Arctic.

The Taiga Plains cover 480,493 square kilometers (185,519 square miles) of the Northwest Territories. This area includes much of the trackless expanse through the core of the territory. The land is characterized by permafrost, peat plateaus, thermokarst lakes, and subdued relief with few significant hill systems.

The Taiga Plains extend from the closed canopy boreal forest in the south to the tree line in the north with its open forest and stunted trees and it includes extensive peatlands. Black and white spruce are the dominant coniferous tree in the region while paper birch is the primary deciduous tree. Toward the south one can find aspen and jack pine in the region’s forests, too, though they are uncommon.

The animals of the Taiga Shield are representative of most of the animals found in the Northwest Territories. There are 50 mammal species and 250 species of permanent bird species with an additional 50 species of birds that visit the territory.

Major bird species in the region include bald eagles, osprey, falcons, hawks, owls, and ducks. The Taiga Shield has important northern breeding grounds for many duck species.

The large mammals include many ungulates (hooved animals) species, such as several caribou species, muskoxen, moose, white-tail and mule deer, elk, and wood bison. There are also many carnivores, including grizzly bears, black bears, lynx, wolves, red foxes.

Smaller animals in the plain’s ecology include marten, mink, wolverines, weasels, beavers, muskrats, porcupines, and many smaller animals. The largest of these animals were hunted and trapped extensively, especially the muskox, during the heyday of the fur trapping Hudson’s Bay Company and North West Company.

The Taiga Shield contains 330,082 square kilometers (127,445 square miles) of remote landscape in northern Canada. The world’s oldest rocks are found in this region near the Acasta River. The bedrock is never far from the surface of the Northwest Territories and, as such, it is very apparent in this region.

The Taiga Shield is very rocky and it is home to a mix of exposed bedrock and glacial till. Periglacial and glacial features are abundant in the region, too. Indeed, the region has over 200,000 lakes, most of which are thermokarst lakes.

Here, the forests are primarily located in the south end of the shield and are similar in composition to the Taiga Plains forests. Black and white spruce are the primary trees in the region while jack pine can be found on occasion in the southern part of the area. Moving north through the region, one can see a change from forest to open shrub and lichen tundra. Here, there are mostly smaller stands of trees rather than large forests.

The shield is a major part of the range for barren-ground caribou species. Muskoxen are present in the region, too; however, their populations are depleted from over-hunting, Meanwhile, moose are fairly new to the region.

Additionally, the shield is a popular region for the denning of tundra wolves. The rest of the animal inhabitants of the region are much the same as the Taiga Plains; however, the unforested areas limit the range of the smaller mammals.

The Cordillera covers 164,351 square kilometers of the Northwest Territories along the border with Yukon. It is a landscape of rugged peaks, rocky ridges, rolling hills, eroded plateaus, and deep “V” and “U” shaped valleys. There are fast moving braided rivers, slow moving meandering rivers, glaciers, and ice fields all found in the region.

Most of the species of birds and mammals are the same as the Taiga Shield and the Taiga Plains; however, there are several species that are unique to the mountain ecology. Trumpeter swans, dusky grouse, and white-tailed ptarmigan live in the cordillera. Many of the bird species that are found in the Northwest Territories cordillera are the same species that nest in the alpine zone of the Rocky Mountains to the south.

Dall sheep and mountain goats inhabit the cordillera, but not the surrounding plains and shield ecologies. Here, one can also find moose, wood bison, lynx, wolves, and grizzly bears.

The Southern Arctic ecology area covers some 168,187 square kilometers (64,937 square miles) of land in the Arctic tundra. This region extends north from the tree line to the Arctic Ocean as shrublands, which are filled with dwarf birch, Labrador tea, alpine bilberry, willows, sedges, cotton-grass, lichens, and mosses.

The vegetation diminishes in volume and size toward the north as one gets closer to the barren coast of the Arctic Ocean. There are fewer animals in this region than the other regions to the south, with only about 30 mammals that inhabit the southern Arctic during the year. The only animal found in the region that is exclusive to the Arctic ecologies of the Southern Arctic and Northern Arctic is the polar bear.

The rivers and streams of the Southern Arctic are unorganized tangles of waterways that shift regularly depending on the season. Birds and waterfowl inhabit the areas surrounding shallow ponds and river deltas because the rest of the water is too deep and too cold to grow the plant communities that feed these birds.

There are approximately 115 species of birds that nest in this region and they have developed some unique survival adaptations. Many species in this region will maintain one area for brooding and one area for molting. It’s suspected that the birds spread out in this way to make it more difficult for predators to attack them.

The islands in the Arctic Ocean make up the Northern Arctic ecological region, which cover 216,771 square kilometers (83,695 square miles) of land. The tundra of the Northern Arctic is barren rock or carpeted with dwarf herb, dwarf shrub, sedge, moss, and lichen.

Peary caribou are the smallest species of caribou in North America and they are only found in the Northern Arctic region. Other animals that are associated with the arctic regions are Arctic hares, Arctic foxes, polar bears and the northern collared lemming.

While there are relatively few mammals that inhabit the islands of the Northern Arctic, there are large populations of birds. Willow ptarmigan, rock ptarmigan, gyrfalcon, snowy owl, and the common raven inhabit the arctic year-round, while other species of birds will migrate south for winter. In fact, it’s believed that ancient bird populations may have sought refuge on the islands during the Pleistocene because the islands were not completely glaciated like the mainland.

While only 45,000 people currently live in the Northwest Territories, the history of the people in the area is both extensive and fascinating. From the Sivullirmiut, the first known inhabitants of the territory to the modern day, here is a summary of the human history of what is now called the Northwest Territories.

Groups of humans started migrating through the ice-free corridor from Beringia, through Alaska, Yukon, and Alberta about 14,000 years ago to inhabit the southern half of North America. However, the Northwest Territories were only free of ice about 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

Furthermore, it took several thousand more years, until about 5,000 years ago, before people attempted to inhabit the north after the most recent glacial maximum. The Sivullirmiut began to inhabit the north, adapting to the arctic conditions as they migrated east. It is possible that the Sivullirmiut became the Dorset culture around 500 BCE; however, this is still unclear.

By 1000 CE, the Thule people had migrated into the territory; however, there is no evidence that the Thule had ever interacted with the Dorset. The Dorset culture had settled further to the south in what is now Quebec and by 1500 CE, had all perished. The Thule are the ancestors of the modern Inuit of the north.

Between 900 and 1600 CE, the first Europeans entered the region that is now called the Northwest Territories. Viking landed in North America and made contact with the inhabitants of the land, sometime during the 1000s CE. While Norsemen certainly landed in eastern Canada and possibly Nunavut, it is unclear if they made it as far west as the current day Northwest Territories.

However, during this time a number of First Nations cultures thrived in what is now the Northwest Territories. There are dozens of First Nations that consider the regions to be their ancestral homelands.

Currently, there are a number of regional and community First Nations governments that have been established in the Northwest territories. These include:

At the end of the Viking age in northern Canada, Europeans began searching for the Northwest Passage, the theoretical route through the Arctic Ocean to reach the lucrative Asian trading markets. The first Europeans to attempt the passage were Martin Frobisher in 1576 and John Davis, the latter of which led three expeditions in 1585, 1586, and 1587. Both sailors were unsuccessful in finding the lucrative trade route.

In 1610, Henry Hudson arrived in the north in search of the Northwest Passage. His journey ended in the massive bay that would later bear his name, in which he was set adrift by a mutinous crew. By 1670 the Hudson’s Bay Company was created and granted a monopoly over the fur trade in Rupert’s Land, what would later become Canada. While Rupert’s Land did not contain the Northwest Territories, the company certainly took advantage of the area for gathering furs.

When European traders arrived in what is now the Northwest Territories, the northern half of the territory was inhabited by a number of First Peoples, including the Caribou, Central, and Copper Inuit. Also, the southern half of the territory is home to a number of Dene First Nations including the Dane-zaa, Chipewyan, Tłı̨chǫ, Tahltan, Sekani, Deh Cho, and Yellowknives.

After European fur traders arrived, the Métis culture was established. Derived from a French word meaning “mixed-blood,” Métis are people of both European and Indigenoush ancestry. The Métis are recognized as one of Canada’s three Indigenous peoples, which include Métis, First Nations, and Inuit.

During the nineteenth century, the fur trade in what is now the Northwest Territories proliferated. Indeed, the fur trade is the reason that the region’s muskoxen have such small populations today. Muskox hide was very desirable during this time, and the animal was nearly hunted to extinction. Thankfully, some survived and have been given the opportunity to continue inhabiting their traditional northern range.

In 1819, Sir John Franklin of Great Britain set out on the Coppermine Expedition to discover the Northwest Passage by overland travel. This doomed expedition led to minimal discovery and charting of the Arctic Coast. The expedition is actually better known for the fact that 11 of the 22 expedition members perished and that Franklin attempted to eat his own boots to stave off starvation.

Before Franklin’s overland expedition to the Arctic Ocean in 1819, the only Europeans recorded to have seen Canada’s northern coast were Samuel Hearne and Alexander Mackenzie. In 1771, Hearne followed the Coppermine River to the ocean, while in 1789 Alexander Mackenzie followed what would later be called the Mackenzie River to the coast. Alexander Mackenzie is best known as the first European to cross North America, north of Mexico. The Mackenzie River was given its English-language name in his honor.

While Franklin was criticized by local fur traders for poor planning and haphazard execution, he was heralded as a hero and praised for his courage in the face of such adversity when he arrived back in Britain. As a hero, he set off again in 1845 with two ships, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, to try to find the Northwest Passage.

Franklin’s second expedition for the Northwest Passage ended in tragedy as both ships became icebound soon after arriving in the Canadian Arctic. The ships were discovered in 2014 and 2016 and are now a Canadian National Historic Site. The expedition had ultimately ended up along the Northwest Passage; however, in 1848, after the ships had been icebound for over a year, the remaining crew attempted to escape overland, but none survived, and the ships eventually sank.

During the search effort for the Franklin Expedition, Robert McClure navigated the Arctic Ocean from west to east and found an ice-bound route that would connect the east to the west as the Northwest Passage. However, it wasn’t until 1906 that the Northwest Passage was finally navigated by boat when Roald Amundsen of Norway traversed the passage in a three-year journey on the ship Gjøa.

Between 1913 and 1918, some of the world’s last major land masses were formally surveyed. Vilhjalmur Stefansson, born in Canada to Icelandic parents, traveled through the Arctic and may have truly been the first person to visit Borden Island, Mackenzie Island, and Brock Island of the Northwest Territories.

On the mainland, oil exploration led to the discovery of the Norman Wells field in 1920, which kicked off over a century of oil production in the Northwest Territories. The bituminous oil was originally recorded by Alexander Mackenzie as he explored the Arctic. His local guide brought Mackenzie to a place where oil was accessible at the surface and the locals would mix the oil with pine resin to waterproof their canoes.

In the 1930, gold was discovered in the region. This discovery started the mining industry that has been ongoing in the territory for nearly 100 years. Since the discovery of oil and gold, mining has become the primary industry of the territory. Copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, and diamonds have been discovered and mined. The current economy of the territory is especially dependent upon the diamond mines.

The Northwest Territories is filled with adventures of the most rugged sort. There are vast tracts of land that few people have ever seen in this wild and remote territory. The following are the most popular areas for adventure in the territory:

Meaning “place where people travel” in Inuvialuktun, Aulavik is one of the most isolated parks in North America. Covering pristine, big-sky barrens of Banks Island, muskoxen are more numerous here than anywhere else in the world. It is also home to the smallest of the caribou, the Peary caribou, as well as snowy owls and gyrfalcons.

There are several amazing things to do in the park. First, you can paddle the Thomsen River, the world’s northernmost navigable river, through the heart of Aulavik. Second, feel free to camp anywhere you would like, so long as it’s not on archaeological sites. Third, hike through the untouched Arctic tundra of the park and experience its beauty first-hand.

Tuktut Nogait National Park is located some 170 km (102 mi) to the north of the Arctic Circle and borders the legendary Northwest Passage. As one of Canada’s least visited parks, fewer people visit Tuktut Nogait National Park each year than orbit the earth. While seldom visited, the park does have some attractions that make the trek here worthwhile.

The landscape is filled with rolling hills and is home to some 68,000 Bluenose caribou that make their calving grounds in the park. There are steep canyons and waterfalls among the three major rivers in the park, too.

Paddling the canyons of the Hornaday River is generally a must-do if you’ve made it to the park. There are also birds in the park, such as peregrine falcons, tundra swans, and jaegers to watch out for when in the area.

Canada’s largest national park was established to protect the last remaining herds of wood bison, the biggest land animal in the Western hemisphere. Indeed, with a total area of some 44,807 sq. km (17,300 sq. mi) Wood Buffalo National Park is the largest of Canada’s national parks and is one of the largest in the world, the size of many European nations, such as Estonia, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

The landscape in the park is made of pine-studded plains, glistening salt flats, karstland caves, and the Peace-Athabasca wetlands. The park is a refuge to some of the world’s last whooping cranes and has a beaver dam so big you can see it from space. Also, as the name implies, there are many buffalo to see.

Wood Buffalo National Park is accessible year-round, which is a rarity for these northern parks. It features some special activities throughout the year, in addition to the regular hiking and exploring that visitors might do. The park hosts an ice festival in which Pine Lake is cleared for skating.

The world’s largest northern picnic takes place in the summer in the park. There is also a paddlefest to take you into the Slave River Rapids with a guided hiking or paddling tour, as well as an annual dark sky festival. Plus, the park is a particularly great place to see the aurora, though you can also see the northern lights throughout the Northwest Territories.

Tucked against the Yukon border, this park is named for the sacred Nááts'įhch'oh mountain that guards the headwaters of both the Nahanni and Natla-Keele river systems. Nááts'įhch'oh National Park Reserve is the traditional home of the Shúhtaot'ine (Mountain Dene). It is also the perfect habitat for grizzly bears, Dall sheep, mountain goats, and woodland caribou.

Popular activities in the park include hiking and paddling. Paddlers can attempt South Nahanni’s “rock garden,” which features 50 kilometers (31 mi) of continuous rapids, or the less technical Broken Skull River. There are no established trails in the park, however, so visitors should come prepared for independent travel in the region.

The Dehcho First Nations welcomes visitors to Nahʔą Dehé, a land of plateaus, wild rivers, and rugged peaks in what is now protected as Nahanni National Park Reserve. The park reserve is a UNESCO world heritage site and is in a different league of outdoor adventure than any of the other Canadian parks.

Towering canyons frame the South Nahanni River as it gushes through the pristine alpine of bears, Dall sheep, and woodland caribou. The earthshaking and soul-inspiring cascade of Virginia Falls, riverside hot springs, burbling tufa mounds, white water rapids, beautiful rivers, and countless peaks to hike are some of the main attractions in the park.

The park is a mountaineering mecca as it is home to some of the few areas of big granite climbing in Canada. Climbers can attempt the daunting Cirque of the Unclimbables and the menacing Vampire Peaks within the park. Additionally, with the Ragged Range of the Mackenzie Mountains, Nahanni has become a playground for mountaineers. There are also many peaks in the park that don’t require mountaineering in order to summit, which makes them perfect for hikers and trekkers.

Established in 2019, Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve is one of the newest parks in all of Canada. It is home to a diverse area of land that stretches from the cliffs of Great Slave Lake’s East Arm northeast to the Barrenlands.

Named “Land of our Ancestors” in Chipewyan, the park is co-managed by members of the Łutsël K'é Dene First Nation, and includes traditional and present-day hunting, fishing, and spiritual areas.

The land of Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve is wild and rugged. There are no official trails to hike, nor designated backcountry camping. The land and water are free to roam and explore. Popular activities include hiking and backpacking, paddling, fishing, sight-seeing flights, and wildlife viewing. These traditional lands are being preserved to share the culture that they have fostered and the beauty of the landscape itself.

Although the Northwest Territories aren’t home to any metropolitan areas on the scale of Toronto, Montreal, or Vancouver, there are quite a few sizable communities in the region. Here are some of the best places to check out when visiting the Northwest Territories:

Located on the shores of Great Slave Lake, Yellowknife is the largest community and only city in the Northwest Territories. It was established in 1934 when gold was discovered in the region and it quickly grew, becoming the capital city of the territory in 1967.

While it only has a population around 20,000, Yellowknife is a modern city with a commercial downtown area that features a number of high-rises. The city has many festivals throughout the year to celebrate music, art, and northern culture.

Yellowknife is the modern center of this vast and traditional land. Adventure starts from the edge of the city, and without leaving the city, you can experience the midnight sun or some of the 200 nights where the northern lights are visible in the territory.

Created in 1953 as an administrative center for the surrounding region, Inuvik was the most northerly town in Canada you could drive to until 2017 when the road to nearby Tuktoyaktuk opened. It is located in the northwest of the Northwest Territories and it is connected to the rest of Canada by the famous Dempster Highway. Inuvik also has a regional airport that receives flights from surrounding major cities.

Tuktoyaktuk is located on the shores Kugmallit Bay, near the Mackenzie River Delta, at the Arctic tree line. It is the most northerly town in Canada that you can drive to on a four-season road. The distinction of four-season road needs to be made, as there are seasonal ice-roads which can lead further north. It became connected to Canada’s highway system in 2017 with the completion of the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway.

Usually referred to as Tuk, the area has been occupied for centuries by the Inuit. The village is small and many people are subsistence hunters and anglers, though most residents of the town work in tourism or transportation.

Explore Northwest Territories with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.