Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

The Carpathian Mountains are a lengthy, diverse range spanning 1,500 km across Central Europe. This swath of densely forested slopes and rocky, alpine peaks covers parts of Poland, Slovakia, Czechia, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Austria, and Serbia. The Carpathian Mountains are the 2nd longest range in Europe, after the Scandinavian Mountains. In total, they include 25923 named peaks, showcasing varied ecosystems, geological formations, human cultures, castles, ski resorts, climbing routes, and hiking trails. The highest peak is Gerlachovský štít (2,654 m / 8,707 ft), in the High Tatra Mountains of Slovakia.

Although the Carpathian Mountains resemble a single chain of mountains, they comprise several discrete parts. Most broadly, the range has three regions: the Western, Eastern, and Southern Carpathians.

The Western and Southern Carpathians contain the only authentic alpine landscapes in the range. They feature the highest peaks, the most snowfall, and the most attractive destinations for alpinists, hikers, and climbers. When people think of the Carpathians, these are the places they commonly picture.

In particular, the High Tatras in Slovakia/Poland and the Transylvanian Alps in Romania are the most mountainous regions.

These subranges share a similar alpine character. They comprise jagged, snowy, prominent peaks topped with alpine grassland ecosystems. Peaks in these areas commonly exceed 2,500 m (8,200 ft).

By contrast, the Eastern Carpathians, which sit between the two extreme ends of the range, are lower, less prominent, and feature more dense forests and rolling hills. The highest peak in the Eastern Carpathians is Pietrosul Rodnei (2,303 m / 7,556 ft) in the Rodna Mountains of Romania. Despite their lower prominence, the Eastern Carpathians are characterized by a rugged wilderness devoid of crowds, a hard thing to come by in Europe.

The Western extreme of the Carpathian Mountains comprises several subranges spanning parts of Austria, Poland, Slovakia, and Czechia. The vast majority of the Western Carpathians sit in Slovakia and cover much of the country’s area.

The major subranges in the Western Carpathians are the Low and High Tatras (which make up much of Tatra National Park), the Low Fatras (Malá Fatra), and the Belianske Tatras. These areas concentrate the vast majority of the visitors and contain most of the notable peaks in the Western Carpathians, but the range stretches far beyond to the east and west.

The outlying foothills stretch as far as Hundsheimer Berg, just over the Austrian border outside Bratislava, Slovakia. To the east, they continue through Eastern Slovakia and Poland as the hilly, sparse Beskids. To the south, they stretch into northern Hungary.

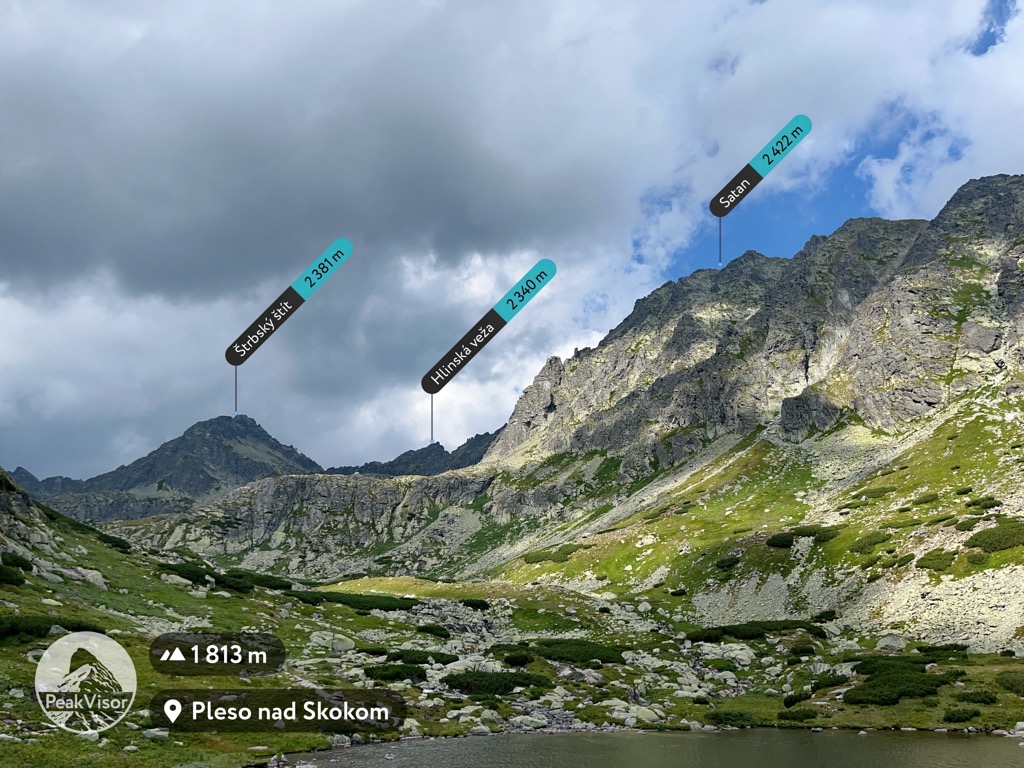

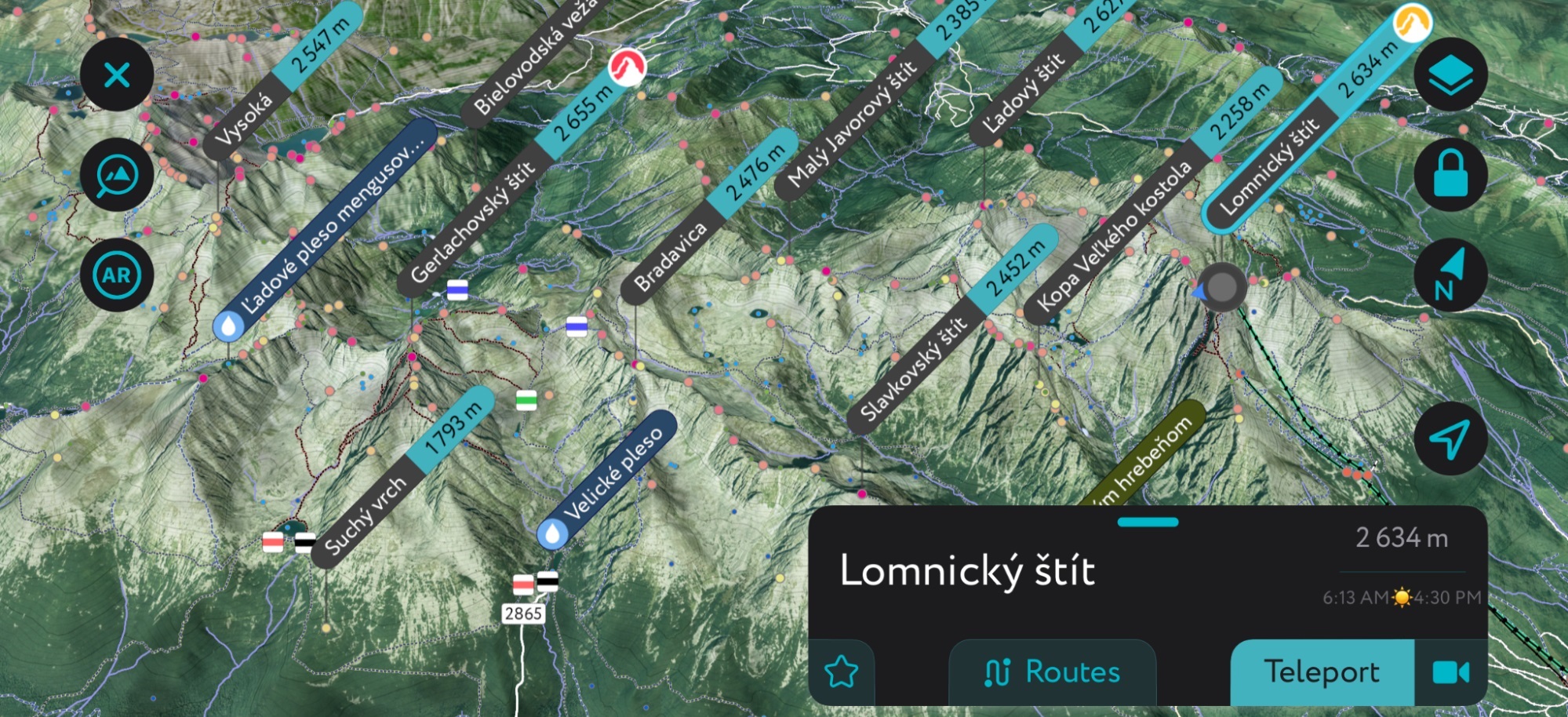

Notable peaks in the Western Carpathians (all of which are in the High Tatras) include Gerlachovský Štít, Rysy (2,503 m / 8,212 ft), Kriváň (2,494 m / 8,182 ft), Lomnicky Štit (2,634 m / 8,642 ft), and Kasprowy Wierch (1,987 m / 6,519 ft).

The most apparent divide between different regions of the Carpathians is the gap between the Western and Eastern Carpathians. Just before the Ukraine border, there is a distinct dip in elevation that forms a pass between the two regions. The Carpathian’s eastern chain is the largest, including parts of Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Romania.

Many maps and sources subdivide the Eastern Carpathians into “outer” and “inner,” but they often disagree on where the divide is. The main subranges in the Eastern Carpathians are the Beskids, the Maramureș Mountains, the Rodna Mountains, and the Harghita Mountains.

The Beskids are the first mountains after the saddle between the Western and Eastern Carpathians. They form a long chain of rounded, hilly mountains and maze-like riverine canyons that stretches from Eastern Slovakia and Poland through Ukraine.

Crossing the border into Romania, the mountains trend higher. Just on the other side of the Ukraine border are two of the most remote and rugged areas in Romania: the Maramureș Mountains and Rodna Mountains. These are some of the most inaccessible parts of the Carpathians, with few roads. Further south, you’ll find Călimani National Park, a dormant volcano that is considerably easier to explore than the Maramureș or Rodna Mountains.

Approaching the Southern Carpathians, the range widens. This area of Romania is sparsely populated but very beautiful, dotted with mountain lakes and rivers. As they continue further south, the Eastern Carpathians become the Southern Carpathians. There isn’t a clear boundary, but a sudden climb as you get closer to the Transylvanian Alps.

The most notable peaks in the Eastern Carpathians are Hoverla (2,061 m / 6,762 ft), Pietrosul Rodnei (2,303 m / 7,556 ft), Pietrosul Călimani (2,100 m / 6,890 ft), and Ineu (2,279 m / 7,477 ft).

For many people, the Carpathians are synonymous with Romania, and it’s easy to see why. While the High Tatras are the highest and most prominent mountains in the chain, the Transylvanian Alps span more area, with more high peaks and larger expanses of alpine wilderness. They also feature some of the best hiking and nature watching you can do in the Carpathians.

While the boundary from Eastern to Southern Carpathians isn’t exact, it’s easy to tell when you have entered the Transylvanian Alps. The mountains shoot up around the foothills to the east into alpine grasslands, boulder fields, and rocky precipices.

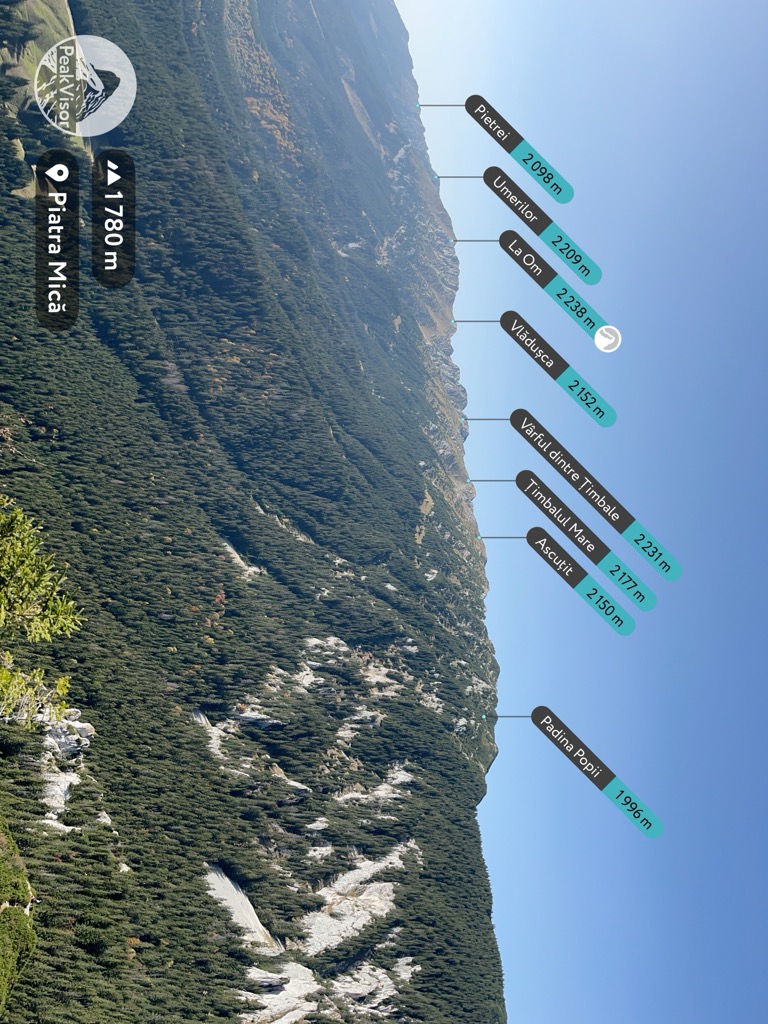

Moving east to west, the first clear subrange in the Transylvanian Alps is the Bucegi Mountains in Bucegi Natural Park. Bucegi sits across a wide valley from Piatra Craiului National Park. Together, these two areas are the most popular hiking destinations in Romania. They are easily accessible from Brașov, even without a car. Many visitors make day trips to the nearby Bran, Sinaia, and Peles Castles as well.

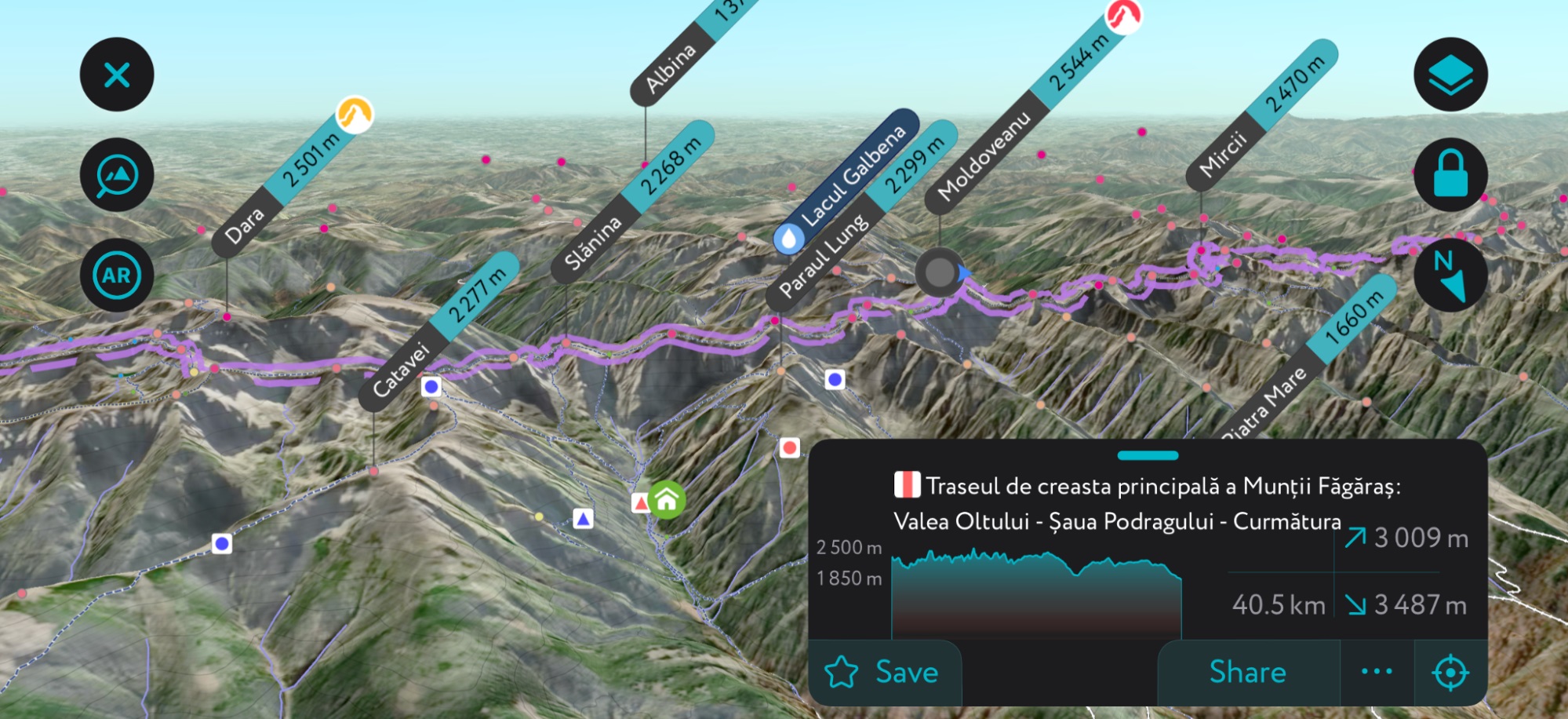

Just beyond Piatra Craiului are the Făgăraș Mountains. Like the High Tatras, mountains in the Făgăraș sit along tall, narrow ridges. There are two ridgelines in the Făgăraș – the larger of the two runs directly east-west, while a smaller one to the southeast sits on a diagonal. The highest point in the Făgăraș Range is Moldoveanu (2,544 m / 8,346 ft), the tallest mountain in Romania. Surprisingly, visitors can drive over the Făgăraș along the Transfagasaran Highway. This winding mountain road provides excellent access to the high country and is easily the best drive in the Carpathian Range.

West of the Făgăraș are two more large ranges: the Parâng and Retezat Mountains. These areas are similarly high and wild, though less accessible to tourists than the Făgăraș or Bucegi. Both the Parâng and Retezat Mountains feature striking alpine valleys and challenging objectives. The remoteness of these areas adds a level of difficulty to exploring them. Sketchy weather, wildlife encounters, and long approaches are all regular fare on this side of the Transylvanian Alps.

Just north of this area are the easily overlooked Apuseni Mountains (Apuseni Natural Park). Apuseni is more similar to the Eastern Carpathians than the Transylvanian Alps, with many forests and riverlands to explore on foot.

Proceeding south into Serbia, the Carpathians drop dramatically. The Serbian Carpathians are significantly more spread out and feature broad, smooth profiles. For comparison, the highest peak in the Serbian Carpathians is Šiljak (1,560 m / 5,118 ft). This point sits less than 200 km from Retezat National Park, where elevations average over 2,000 m (6,561 ft).

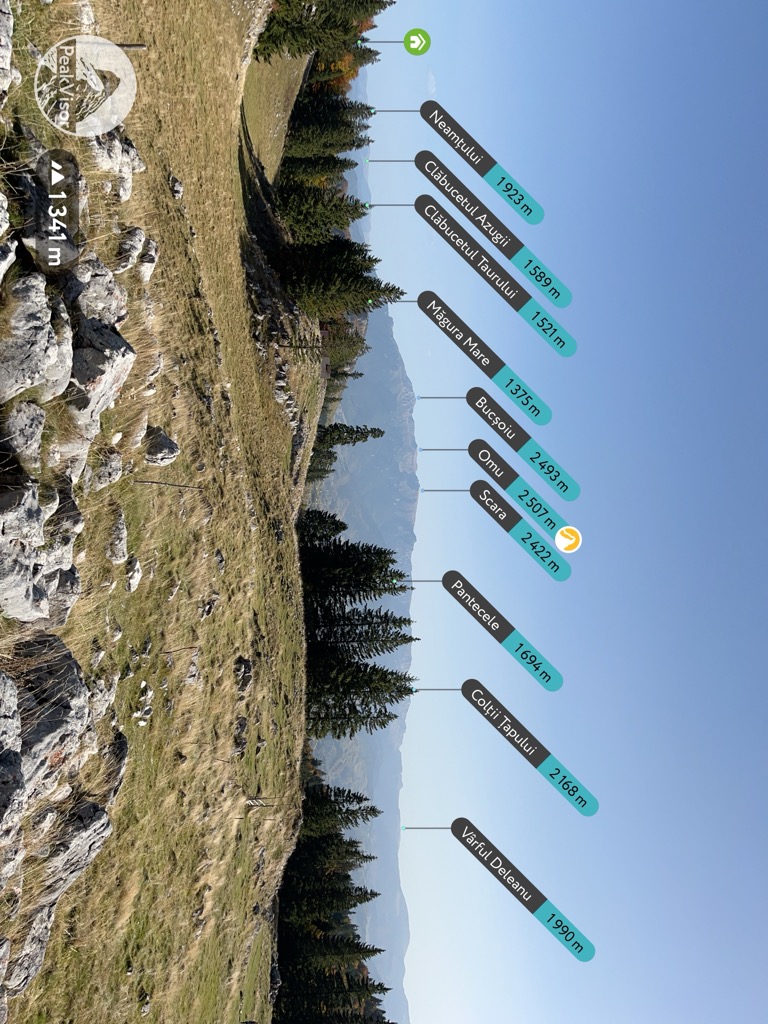

The most notable peaks in the Southern Carpathians are Moldoveanu, Parângul Mare (2,519 m / 8,264 ft), Omu (2,507 m / 8,225 ft), Peleaga (2,509 m / 8,232 ft), and La Om (2,238 m / 7,343 ft).

Depending on which part you want to visit, getting from the airport into the Carpathians can be a piece of cake or a logistical headache.

For example, the High Tatras are straightforward to get to, even without a car. On the Polish side, you can take a two-hour bus from Krakow to Zakopane for about 50 PLN (11€). On the Slovak side, there is a central train station (Poprad Tatry) and a smaller rail network (the TEŽ), which services all the small towns around the base of the mountains.

The Southern Carpathians are more mixed in terms of accessibility. It is relatively easy to get to Bucegi and Piatra Craiului by public transport.

For Bucegi, the easiest access route is to take a train to Bușteni or Sinaia and then take the cable car onto the Bucegi Plateau. The cable car runs every day, year-round. The train costs around 20 RON (4€) and takes an hour. Rides on the cable car are more expensive, around 200 RON (40€) for a return trip.

There are also private cars for hire in Bușteni, but prices range depending on who you talk to. Taking a car to the Bucegi Plateau will often cost as much as the cable car. Because getting onto the plateau can be time-consuming, it’s wise to stay in Bușteni or Sinaia.

The best jumping-off point for Piatra Craiului is Zărnești. You can easily get to Zărnești from Brașov by train for around 5.50 RON (about €1). Taxis can also be helpful to get to and from trailheads. Uber and Bolt are easier to use if you don’t speak Romanian, but aren’t as reliable as in the big cities.

The rest of the Southern and Eastern Carpathians are challenging to explore without a car. Renting a car in Romania is easy and cheap (just remember to get an International Driving Permit if coming from outside the country). If you rent a car in a smaller city like Timișoara or Cluj Napoca, cars can be as cheap as 20 RON (5€) per day. Therefore, it’s an excellent option for exploring places like the Retezat, Parâng, and Maramureș Mountains.

Geologically speaking, the Carpathians are a young range. They formed during the Alpine Orogeny (uplift) that also created the Alps around 65 million years ago. The rock pushed up to form the mountains varies wildly depending on what part of the range. The High Tatras feature slick granite buttresses, while many places in the Southern Carpathians are full of limestone and sandstone.

Since the Orogeny, the rock has eroded over several ice ages. In many places, it’s easy to see where massive glaciers carved out U-shaped canyons, particularly in the High Tatras. Wind, water, and sun are important secondary erosive factors.

The Southern Carpathians have been sculpted by rivers, creating characteristic V-shaped canyons. Because the Carpathians lack the extreme elevation of the Alps, the glaciers receded after the last ice age and never returned. Even summer snowfields in the Carpathians are rare and depend on year-to-year snowfall.

The erosive processes on the underlying bedrock have created diverse rock formations across the range. The High Tatras are full of granite buttresses and glacial polish. Though much of Tatra National Park is unestablished, it has enormous potential as a rock climbing destination. In the Transylvanian Alps, erosion has formed over 12,000 limestone caverns, many of which are open to the public. Other places like Bucegi Natural Park feature sandstone pillars and monoliths like The Sphinx.

The Carpathian Mountains may not have the impressive altitude or year-round glaciers of the Alps, but they have wilderness. The huge spans of old-growth forest and alpine grasslands across the Carpathians are some of the only true wilderness habitats remaining in Europe. They are a hub of biodiversity, and as much as 30% of European plant species can thrive here. These mountains also provide a habitat for charismatic and elusive animals not found elsewhere in Europe.

The most significant factor for ecosystems in the Carpathians is elevation. The lower foothills and peaks are often covered in rolling forests, while the few alpine areas feature carpets of wildflowers and grasses.

The lower elevations of the Carpathians are immediately recognizable. They feature rolling mountains covered in thick deciduous forests. Many of the low-elevation forests here are old-growth, highly-developed ecosystems that have been unchanged by human hands for hundreds of years. Some are so pristine that human beings have never directly altered them over the course of history.

Most of these are the primeval beech forests found throughout the Carpathians. These are some of the only ecosystems in Europe unaffected by logging, where the processes of growth and decay have been playing out for millions of years. Ancient forests are bastions of biodiversity and are highly valuable to conservation. The most significant areas of unfragmented forest in Europe are in the Southern Carpathians of Romania.

As you might expect, these areas are threatened by illegal logging and climate change. Fortunately, there are ongoing conservation efforts to protect crucial pieces of forest and repair damaged areas.

Gaining elevation, mixed forests of oak, beech, maple, and sycamore trees give way to conifers like fir, spruce, and larch. Larches are commonly associated with the polar regions but do well in the cold climates of the mountains.

These forests are home to many animals. Predators like bears (particularly in Romania), wolves, lynx, and wildcats stalk grazers like roe deer, red deer (Eurasian elk), and smaller animals like beavers and trout. Brown bears are not usually interested in hunting and mostly eat mushrooms, berries, nuts, and roots. Overhead, visitors commonly spot birds like the golden eagle, black stork, eider duck, osprey, and great spotted woodpecker. On the forest floor, you might see amphibians like the fire salamander.

Carpathian forests are also home to a large, vicious predator: the greater noctule bat. These nocturnal carnivores are straight out of a vampire myth. They have wingspans up to 46 cm (18 in) across and primarily eat songbirds. In classic bat fashion, they are also very mysterious. Despite being the largest bat in Europe, they are not well-understood and rarely seen. Although they are known to exist throughout the deciduous forests of Europe and western Asia, the IUCN classifies these elusive bats as ‘vulnerable.’

Alpine trees are stunted and close to the ground, taking on Krummholz form. Above this is the treeline, where the mountains become too exposed to support trees.

The alpine regions of the Carpathians are full of rugged, grassy boulder fields and polished swaths of stone once worn smooth by glaciers. In the summer months, the alpine grasslands are full of wildflowers and herbs, which draw grazers like the Tatras Chamois, a goat-antelope unique to the High Tatras. With keen eyes, visitors may also spot marmots, foxes, and mustelids like the pine marten.

Bear safety is a big issue in The Carpathians, particularly in Romania. Romania is home to 92% of the bears in Europe outside of Russia, with a population of around 8,000. Though these bears are often distinguished from the grizzly bears in North America, they are the same species (Ursus arctos). Don’t let a difference in subspecies lull you into a false sense of security. Grizzly or not, brown bears are territorial and dangerous to people.

Luckily, that doesn’t mean they seek out conflict. Brown bears tend to avoid human contact when possible. Most brown bear attacks happen when a bear is surprised by a human. So, the best thing you can do to avoid confrontation with a bear is to warn them that you’re entering their habitat. Use bear bells to make noise while hiking (clapping, talking, or the occasional “Hey bear!” also works), alerting bears to your presence before you get too close. When bears hear a human approaching them, their most common response is to move away.

In general, the best advice for avoiding dangerous encounters with wildlife is to leave them alone. Even predatory animals are rarely dangerous unless provoked by a curious (or just plain foolish) hiker.

The name Carpathian comes from the Carpi, a Dacian tribe that lived in Eastern Romania in the second and third centuries. The word carpi, meaning “cliff” or “peak,” comes from the Proto-Indo-European language and has been integrated into several modern languages. Variants (like “karpë” in Albanian and “karpyti” in Lithuanian) always refer to jagged mountain terrain.

Modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) arrived in the Carpathians around 30,000 years ago. But long before that, another species of humans, Homo heidelbergensis, lived in the Carpathian Basin (now Hungary). H. heidelbergensis is the most recent common ancestor of our species and Neanderthals. They existed in the area around 470,000 years before modern humans.

In recent history, the Carpathians have been home to several highly cultivated civilizations. The Dacians, Celts, Goths, Romans, and Ottoman Turks occupied parts of the Carpathians for long periods.

Today, the group most commonly associated with the Carpathians is the Gorals. Also called Highlanders, the Gorals originate from the Western Carpathians in Slovakia, Poland, and parts of Czechia. They are the only surviving culture of people specific to the Carpathians and a proud part of the modern culture of the area. Visitors to the High Tatras will commonly see performers playing local folk music in traditional Highlander attire.

The Carpathians have a well-earned reputation for being a haunted, dark, or “spooky” place. Maybe it’s the centuries of feudalism, war, and conquest in the range’s history. Perhaps it’s because the myth of the vampire was born in Romania. Or maybe it’s that Bram Stoker’s Dracula is set in Transylvania. But in truth, some of human history’s most frightening figures have called these mountains home.

The most famous figure in Carpathian history is Vlad Dracula (Vlad the Dragon). Vlad ruled Wallachia during the 15th century, a volatile time in the area’s history. He was a notoriously cruel ruler who waged bloody wars against the Ottomans and the Saxons for several decades. He had a widespread reputation as a talented warrior and a ruthless commander who demanded fear from his enemies and subjects.

Historians estimate that Vlad Dracula killed a staggering 80,000 people during his reign. These included men, women, and children, a significant portion of which were impaled on his orders. His ruthless and gruesome style of warfare earned him the moniker Vlad the Impaler and inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Another figure that adds to the legendary spookiness of the Carpathians is Elizabeth Bathory. Bathory was a prominent ruler in what is now Slovakia. She was an accused serial killer, said to have murdered around 300 women to steal their youth. After accusations started to fly, she was imprisoned (some accounts say walled up) inside Csejte Castle. Stories of her crimes have become mythical, but modern historians dispute them. More likely, the tales of Bathory’s elaborate violence were fabricated by the Habsburgs to remove her from power.

Compared to the nearby Alps, the Carpathians are much easier to see during the warm season. The lower elevation profile of the range creates a long summer season prime for exploring the peaks and valleys on foot. There are hundreds of fantastic trails in the Carpathians, many of which are still well-kept secrets.

Most visitors to the Western Carpathians head to the High Tatras. The lure of the High Tatras is their prominence and alpine character. The upper elevations of Tatra National Park feature impressive knife ridges, alpine meadows, and glassy mountain lakes. In addition to the scenery, this is one of the most accessible places in the Carpathian Mountains. Whether or not you have a car, there is ample infrastructure to help you get into the high country.

However, the park does limit where you can go and which peaks you can climb. Major high points like Gerlachovsky Štit and Lomnicky Štit are off-limits without a certified guide. Some of the most popular routes here include the Rysy through hike, which crosses the national border from Poland to Slovakia, Kriváň Peak, and Tery’s Hut via Studená Dolina.

The area between Eastern Slovakia and Northern Romania is one of the most inaccessible parts of the Carpathian Mountains. What the Eastern Carpathians lack in altitude and jaggedness, they make up for in their untamed splendor.

Because there aren’t as many touristy spots in this region, most of the trails in the Eastern Carpathians are long, multi-day backcountry treks. Avid backpackers will fall in love with places like Rodna Mountains National Park, Maramureș Mountains Natural Park, and Călimani National Park.

Aside from the High Tatras, the Southern Carpathians are the most popular destination for hikers in the range. But they include some of the most dramatic sights in the entire Carpathians. Dense old-growth beech forests full of gothic castles give way to spiny knife ridges, spires of limestone tower over shaded canyons, and wildlife roam freely.

The national parks in this area vary in their ease of access, but all are worthy destinations for hikers. The furthest east and most accessible is Bucegi Natural Park. Bucegi is an elevated plateau that towers over the surrounding canyons. The central high point here is Omu Peak, accessed with the help of a cable car from Bușteni.

Next is Piatra Craiului National Park, a set of two prominent ridges intersecting at a right angle. Popular routes involve steep ascents through striking limestone gorges. The highest point in the park is La Om (2,238 m / 7,343 ft).

Beyond Piatra Craiului are the Făgăraș Mountains. The Făgăraș form an imposing wall visible from all over the Transylvanian Plateau. With the help of the Transfagașaran Highway, visitors can easily access the upper elevations, including Moldoveanu, the highest mountain in Romania.

Continuing south and west, you run into the Parâng and Retezat Mountains. These areas are less not frequented by international tourists but are popular with locals. Parângul Mare and Peleaga are two common objectives here. Peleaga can be done in a day (provided you have a car to get to the trailhead). Parângul Mare is the most prominent peak in Romania and requires a more challenging approach from the highway.

Romania recently finished creating its own version of the Camino de Santiago in Spain, the Via Transilvanica (or VT). This cross-country hike begins on the Ukraine border and ends on the banks of the Danube south of the Transylvanian Alps. It crisscrosses through the Transylvanian Plateau over 1,400 km (870 mi), taking hikers months to complete.

People have only started hiking the entire route recently, but there are detailed resources to help plan where you will sleep and checkpoints to see along the way. The VT is now the longest through-hike in Romania and one of the most epic journeys through the Carpathian Mountains.

Because of their lower elevation and geographic location, the Carpathians tend to get much less snow than the Alps. The ski season is shorter, and the average snowpack is much lower. But there are still plenty of places to ski here, particularly in the Western and Southern Carpathians.

There are a handful of ski fields in the High Tatras. Most consist of a few chairlifts or rope tows covering a few hundred meters of slope meant for beginners. The two that stand out are Tatranska Lomnica Resort in Slovakia and Kasprowy Wierch Resort in Poland.

Tatranska Lomnica offers plenty of vertical drop; top to bottom, you can ski a full 1,300 m (4,265 ft) vertical in a single run. But the downside is that there is really only one run on the mountain, and it goes straight down from the summit. Don’t expect much off-piste tree skiing or deep powder here. But there is some appeal to skiing such a massive face in one run, and the views from the summit are outstanding.

Kasprowy Wierch is more wide-open, encompassing a large area on the north face of the High Tatras. It has many more groomed runs and often nets more snow than Tatranska Lomnica, which is south-facing.

The most popular destination for local skiers in Romania is Poiana Brașov, north of Bucegi Natural Park. The resort includes two chairlifts, two trams, and a gondola and covers about 700 m (2,296 ft) of elevation. It’s not especially steep, averaging between 20 and 30 degrees, but it has a lot of runs to spread out on and more open space than the other Carpathian resorts.

Further to the south, Valea Soarelui (Sunny Valley) Sinaia sits much higher but covers less elevation than Poiana Brasov. The ski fields spread across two faces of the Bucegi Mountains above the town of Sinaia. The resort includes four lifts and one gondola, which runs to and from town.

If you’re coming to the Carpathian Mountains by plane, you will most likely fly into one of the following cities.

The nearest airport to the High Tatras is Krakow, which also happens to be one of the best cities in Poland. It’s a city of around 750,000 people with an international airport and accommodation options to suit all budgets, from budget hostels to luxury hotels. The medieval old town and Jewish district are both full of culture and great food, and there are plenty of other attractions near the city.

Getting to Zakopane (the Polish side of the High Tatras) from here is easy; just take a bus from Dworzec Bus Station. Buses run between six and 12€ and take about two and a half hours to reach the mountains.

Cluj Napoca sits between the Apuseni Mountains and Rodna Mountains National Park on the Transylvanian Plateau. It’s a decent-sized city of around 250,000 with an airport. If you’re arriving by train from Hungary, this is an excellent first stop in Romania. But to get to either Apuseni or the Eastern Carpathians, you’ll almost definitely need a car. As I’ve already mentioned, the good news is that car rentals in Cluj are very cheap, sometimes just a few euros per day. The city itself is not a major destination but does have some authentic Transylvanian flavor and lovely architecture.

Most of the Romanian Carpathians are very sparsely inhabited. The main exception is Brașov, a medium-sized city of around 250,000, with a large train station and an airport. The city itself backs up to the foothills of Bucegi Natural Park, and there are a few scenic hikes you can take into the hills outside of town. The city itself is very picturesque and full of interesting architecture, like the Black Church.

Technically, Brașov is close enough to make day trips to both parks, but if you want to spend multiple days hiking, it’s better to be in one of the small towns just outside each park.

If you want to see Bucegi, take a train from Brașov North Train Station to Bușteni or Sinaia, about an hour to the south, for around 2€. If headed to Piatra Craiului, you can take a bus to Bran (home of the famous “Dracula Castle,” as described in the book) or a train to Zârnești. The bus to Bran is about 3€, and the train to Zârnești is about 2€. Buses run from Autogare 2, west of the north train station.

Bucharest is the largest city near the Carpathians, with a population of 1.75 million. It’s not as much of a tourist destination as nearby cities like Budapest. However, there are still good museums and beautiful buildings that give the city character, like the Palace of Parliament and the Romanian Athenaeum.

The quickest way into the mountains from Bucharest is to take a train toward Brașov. Trains run this route from Bucharest Nord station every half hour, and you should stop in both Sinaia and Bușteni along the way. If you’re renting a car, you could also easily head to the Făgăraș or Parâng Mountains.

Explore Carpathian Mountains with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.