Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

The Apennine Mountains or the Apennines are the main mountain system of Italy. It stretches as a series of linked mountain ranges for more than 1,200 km (750 mi) along the Apennine Peninsula, from which it gets its name. It covers the entire country except in the north, where the Po River Plain lies, beyond which the Alps begins. The main feature of the system is its most extensive mountain range, the Gran Sasso d’Italia ("Great Stone of Italy") massif, located by natural coincidence approximately in the center of the peninsula. It also includes the highest and the most prominent mountain of the entire Apennines—Corno Grande—Vetta Occidentale (the “Great Horn”—Western Summit) of 2,912 m (9,554 ft). The massif is also the Gran Sasso and Laga Mountains National Park, which includes another neighboring mountain range. In total there are 19280 named mountains in the Apennines.

According to the generally accepted version, the name of the range comes from the Celtic word "penn," which means "mountain" or "summit", or "peak", or the like. The Celtic origin is explained by the fact that in the beginning the word described only the northern part of the mountain system, where this largest European ancient tribe lived, before the arrival of the Romans.

The name of the system in Italian is Appennini, in other languages: Apennin (German), Apennins (French).

The Apennines extend for more than 1,200 km (746 mi) along the entire peninsula of the same name on which most of Italy is located: from the island of Sicily in the south to the Ligurian Alps, the southernmost mountain range in the Western Alps, in the north, with which the Apennines collide west of the major city of Genoa.

If we look closer, the mountain system stretches along the peninsula not in a straight line, of course, but wriggles like a snake:

As a result, these mountains are also divided for convenience into three main parts: the Northern Apennines (Appennino settentrionale), the Central Apennines (Appennino centrale), and the Southern Apennines (Appennino meridionale). But, of course, it's not that simple.

In addition to the mountains, which will be discussed below, among other individual features of the landscape of the system, the following should be singled out for one reason or another:

The main thing to know about the origin of the Apennines is that geologically they are a separate mountain system from the Alps, although previously it was thought the opposite, because of their geographical proximity.

The Apennines are about two to three times younger than the Alps. They appeared between 65 and 20 million years ago during the Cenozoic Era (Miocene and Pliocene epochs). This long geological process is called the Apennine orogeny. These mountains rose out of the ancient Tethys Sea as a result of its shallowing. The Alps appeared about 65 million years ago during the Mesozoic Era or the Alpine orogeny as a result of the collision of the African and European tectonic plates.

However, the mountain systems also have similarities—because of the presence of the Tethys Sea in the past, both are composed mainly of marine sedimentary rocks: shales, clay, sandstones and limestones, dolomites, marl, and others, except the Central Alps (one of the three large parts of the Eastern Alps according to the classification of the German-Austrian Alpine Club, AVE), which are mainly composed of crystalline rocks: granite, gneiss, slate, and others.

Given the size of the Apennines, which cover the entire namesake peninsula, they consist of a large number of separate but related ranges and subranges or groups with 12,127 named mountains in total. Their classification is rather confusing, but I will help you to understand it.

The entire mountain system is divided in two main ways: by latitude or north to south, and by longitude or west to east. The first includes the Apennines proper, the second includes the Preapennines or the foothills, which are more often called by the well-established and unusual term the Antiapennines (but that is not the only name), whose existence you might not even have guessed before, right. And, in my opinion, with all due respect to the main range of the Apennines, they are no less or maybe even more interesting to explore than the former.

The Antiappenines is a generic name for mountains that geographically are the same as the main snake-like range of the Apennines, but, if you look closely, they are separated from it by deep valleys and wide mountain trenches. The second reason why they are singled out as separate mountains is geology: They have stones of other compositions, such as the Apuan Alps, where there is a lot of marble, and so this range served as the main source of it for paving streets and cladding buildings of Rome. This part of the Apennines contains other unusual mountains like the world-famous volcano Vesuvius or Monte Circeo (541 m / 1,774 ft), where Odysseus himself spent a couple of years.

A special note about the mountains of Sicily. Some sources refer them to as the Apennines calling them the Sicilian Apennines (Appennino siculo) with the highest peak Pizzo Carbonara (1,979 m / 6,492 ft), others do not, allocating them to a separate range, Sicily Mountains, or rather a group of three relatively small ranges: Monti Peloritani, Monti Nebrodi, and Madonie. The most famous mountain of Sicily, volcano Etna, in turn, is considered a separate peak.

So what follows is a classification of the Apennines. Be patient—the list will be long, but you will find more gems in it. Closer to the center, I also leave the original Italian names of the mountain groups for maximum accuracy.

In general, the Apennines are separated into four big and several smaller parts with the following regions, the main subranges and the highest mountains in each of them:

1.1. The Ligurian Apennines (Appennino ligure): Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Toscana—Monte Maggiorasca (1,804 m / 5,918 ft)

1.2. The Tuscan-Emilian Apennines (Appennino tosco-emiliano): Tuscany, and Emilia-Romagna—Monte Cimone (2,165 m / 7,103 ft)

1.2.1. The Tuscan Apennines Subranges

1.2.2. The Emilian Apennines Subranges

1.3 The Tuscan-Romanian Apennines (Appennino tosco-romagnolo): Tuscany, Romagna (a historical region in the southeast of the present-day Emilia-Romagna region), the Republic of San Marino, and partly Marche and Umbria—Monte Falco (1,658 m / 5,439 ft)

1.3.1 The Tuscan Apennines Subranges

1.3.2. The Romanian Apennines Subranges

2.1. The Umbrian-Marchigian Apennines (Appennino umbro-marchigiano): Umbria, Marche, Lazio—Monte Vettore (2,476 m / 8,123 ft)

2.1.1. Eastern Subranges

2.1.2. Central Subranges

2.1.3. Western Subranges

2.1.4. Ellissoide di Cingoli (Ellipsoid of the commune of Cingoli)

2.1.5. Monte Conero (Monte d’Ancona)

2.2 The Abruzzo Apennines (Appennino abruzzese): Abruzzo, Lazio, and Molise—Corno Grande—Vetta Occidentale (2,912 m / 9,554 ft)

2.2.1. Eastern Subranges

2.2.2. Central Subranges

2.2.3. Western Subranges

3.1. The Samnium Apennines (Appennino sannita): Sannio (a historical region inhabited by the Samnites tribe in the southwest of the present-day regions of Molise, and Campania)—Monte Miletto (2,050 m / 6,725 ft)

3.2. The Campanian Apennines (Appennino campano): Campania, Basilicata—Cervialto (1,809 m / 5,935 ft)

3.3. The Lucanian Apennines (Appennino lucano): Campania, Basilicata, Calabria—Serra Dolcedorme (2,267 m / 7,437 ft)

3.4. The Calabrian Apennines (Appennino calabro): Calabria—Serra Dolcedorme (2,267 m / 7,437 ft)

In general, the Antiapennines or the Preapennines are divided into four big and several smaller parts with the following regions, the main subranges and the highest mountains in each of them:

The Antiapennines Main Range is a range of mountains corresponding to the watershed between the Tyrrhenian and Ligurian seas to the west and the Adriatic and Ionian seas to the east.

2.1. The Tuscan Subappennines (Subappennino toscano): Tuscany—Monte Pisanino (1,946 m / 6,384 ft)

2.2. The Lazio Subappennines (Subappennino laziale): Lazio—Monte Tancia (1,292 m / 4,238 ft)

2.3. The Abruzzo and Molise Subappennines (Subappennino abruzzese-molisano): Abruzzo, and Molise—Monte Castelfraiano (1,412 m / 4,632 ft)

2.4. The Dauno Subappennines (Subappennino dauno): Daunia (a historical region in the present-day Apulia (Puglia) region), Campania—Monte Cornacchia (1,151 m / 3,776 ft)

3.1. The Tuscan Antiappennines (Antiappennino toscano): Tuscany—Monte Amiata (1,738 m / 5,702 ft)

3.2. The Lazio Antiappennines (Antiappennino laziale): Lazio—La Semprevisa (1,536 m / 5,039 ft)

3.3. The Campania Antiappennines (Antiappennino campano): Campania—Monte Sant’Angelo a Tre Pizzi (1,444 m / 4,737 ft)

3.4. The Apulo-Garganic Antiapennines (Antiappennino apulo-garganico): Apulia (Puglia), including Gargano (a historical region in the present-day province of Foggia), and Basilicata—Monte Calvo (1,056 m / 3,464 ft)

The peaks in the Apennine Mountains are modest in elevation, all of them sit below 3,000 m (ft). The highest summit of the range, Corno Grande—Vetta Occidentale, which is translated from Italian as “Wester Summit of the Big or Great Horn”, towers over the surrounding landscape at 2,912 m (9,554 ft). It is also the most prominent Ultra-mountain (2,473 m / 8,113 ft).

In addition, there are several other Ultra-peaks in the Apennines: Monte Amaro (2,793 m / 9,163 ft, prom: 1,813 m / 5,948 ft), Serra Dolcedorme (2,267 m / 7,437 ft, prom: 1,711 m / 5,613 ft), Montalto (1,956 m / 6,417 ft, prom: 1,700 m / 5,577 ft), and Monte Cimone (2,165 m / 7,103 ft, prom: 1,575 m / 5,167 ft).

A little more entertaining geography—the extreme mountains of the Apennines according to the four parts of the world:

Among the other important peaks of the Apennines, of course, I must mention Rome’s famous seven hills: the very low Aventino (51 m / 167 ft), Capitolino (59 m / 193 ft), and Palatino (57 m / 187 ft) in the city center near the Colosseum (I hardly even noticed them while walking in Rome), and the more distant and higher ones to the northeast of the center: Celio (59 m / 193 ft), Esquilino (88 m / 288 ft), Quirinale (38 m / 124 ft), and Viminale (43 m / 141 ft).

The only mountain in the city-state of the Vatican, which you are also sure to visit, is called the same — Monte Vaticanus (83 m / 272 ft). Yes, it has a mountain!

More: Vatican is not the only inner state of the Apennines, there is also the Republic of San Marino in the northeast of the range with its highest peak, Monte Titano (739 m / 2,445 ft).

Except for its pure and wild nature, ancient myths, cultural diversity, and religious relics are abundant in the Apennines, making it an ideal place for hiking and exploring.

Most of the Apennine mountainous area belongs to natural parks, nature reserves, and other green areas. This is another clear difference from the Alps, where, of course, there are also many parks. But in the Apennines, they literally follow one another, so the opposite happens—it is harder to choose an area to hike than to find one.

As in the world as a whole, these are the largest and most important natural areas in Italy. Of its 25 national parks, 15 are located in the Apennines, that is, about 2/3. From my personal choice, here’re the five main ones in the Apennines from north to south with an overview of each of them:

Cinque Terre National Park (Parco nazionale Cinque Terre). It is the main park in the northern Apennines, located on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea north of the town of La Spezia.

The park is named after five villages or lands (terre in Italian) — Monterosso al Mare, Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola, and Riomaggiore—built literally on rocky cliffs and in picturesque bays as fishing settlements, which due to their picturesque location over time have become one of the main tourist attractions of Italy together with Venice and others — alas, rather in a bad way.

Next I asked a colleague who also hikes a lot in the Apennines to tell about the main trails in the park, as well as the other four:

“The main hiking trail in the park is the Blue Path (Sentiero Azzurro). It is divided into four sections and connects all the villages. The total length is about 12 km (7.5 mi) but some of the sections can be closed as an attempt by locals to limit the influx of tourists. This trail along the Ligurian coast is of great scenic and cultural value. The layout and disposition of the small towns and the shaping of the surrounding landscape, overcoming the disadvantages of steep, uneven terrain, encapsulate the continuous history of human settlement in this region over the past millennium.

Sibillini Mountains National Park (Parco nazionale dei Monti Sibillini). Sibillini Mountains are named after Monte Sibilla (2,173 m / 7,129 ft) where the Sibyl, a sort of witch with extraordinary powers, was believed to dwell.

Most of the peaks of this range are over 2,000 m (6,561 ft). The highest is Monte Vettore (2,476 m / 8,123 ft). Since 1993 the area has been part of the namesake national park. Thanks to a long tradition of sheep-farming culture, today we can easily access these mountains through well-established sheep tracks. Important: due to a severe earthquake in 2016 some trails may be still closed.

The main (and the longest) hiking route in the park with the name speaking for itself is the “Sibillini Mountains Great Ring” (Grande Anello dei Sibillini) of 120 km (75 mi). However, like all long hiking routes, it consists of shorter sections you can hike. In the “Ring,” there are 9 of them.

Gran Sasso and Laga Mountains National Park (Parco nazionale Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga) is one of the largest and most precious, protected areas in Europe.

Here, the great natural treasures live alongside amazing cultural heritage. Snow can continue to fall on the park’s highest mountain, Corno Grande, until late May and remain thick in summer as well. If you’re going to do any of the Gran Sasso trails, I recommend you to have the CAI Gran Sasso d’Italia map in addition to the PeakVisor app.

The main hiking route in the park starts from Pomilio Hut and is meant to satisfy the most fastidious hikers.

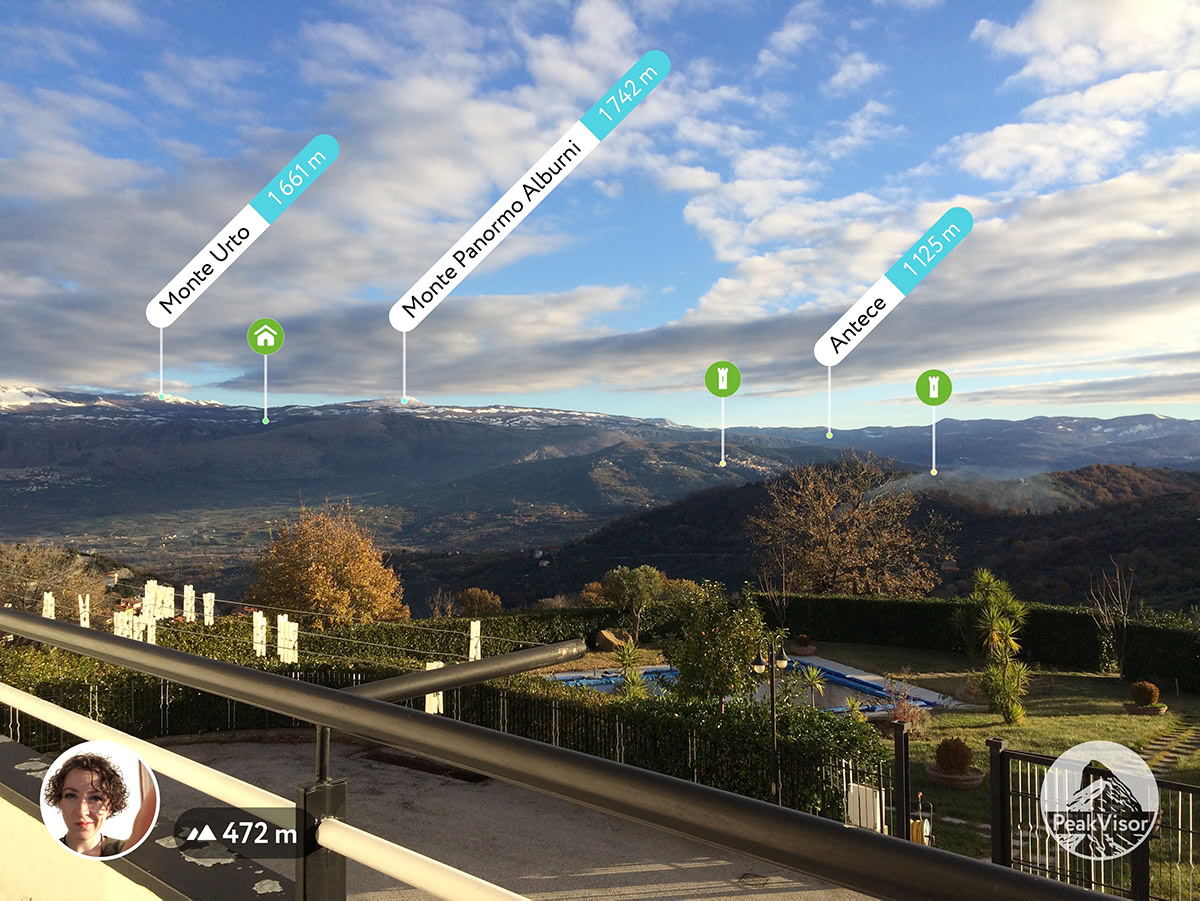

Cilento, Diano Valley, and Alburni Mountains National Park (Parco nazionale Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni). Cilento in Campania is a mountainous area, as well as a famous UNESCO World Heritage Site, due to its long history and the permanency of ancient agricultural traditions.

The park is a lesser-known paradise of jagged coastline and inland hills that combine beautiful seas with green natural splendor but it is a world away from the crowds and tourist shops. Here you will find street markets where the locals shop and small stores for everyday life. The most important range of this region is the Alburni Mountains, also called the “Southern Dolomites” or the “Dolomites of Campania”, due to their resemblance to their northern cousins.

The main hiking route in the park is a walk on Monte Panormo (1,742 m / 5,715 ft), also known as Alburno, which will lead you to Panormo Hut starting from Ottati village, right on the mountain top, going through beech woods and sheep tracks. In addition, there are a few trails that go to the locally important Santuario della Madonna Delle Nevi (Virgin Mary of the Snow Sanctuary).

Sila National Park (Parco nazionale della Sila). The namesake Sila Mountains are located in Calabria, between Catanzaro and Crotone, on the Calabrian Apennines. The highest peak is Monte Pollino (2,248 m / 7,375 ft).

Occasionally, the Sila woods remind us of the Scandinavian Mountains panorama. The area is particularly rich in flora and fauna. In particular, it is one of the last and most populated bulwarks for wolves in Italy—with about 31 trails waiting to be explored.

The main trail in the park is a challenging 6-hour trail to the second-highest peak of Sila Mountains, Montenero (1,881 m / 6,171 ft), on the slopes of which you can find pseudo-dolmenic monoliths. The trail goes from the village of Cagno via Arvo Lake from May to October.”

All other national parks in the Apennines are the following:

In addition to national parks, the Apennines have even more regional nature parks, the second-largest type of natural areas by size. These parks are more popular with locals than tourists, which means you will find fewer of the latter in them.

For example, I would recommend visiting Aurunci Mountains Nature Park (Parco naturale dei Monti Aurunci), a relatively large mountain range between Rome and Naples. Thanks to its coastal location, you can see almost all of the Tyrrhenian Sea coast in this part, including Vesuvius, from the park's highest mountain Monte Petrella (1,533 m / 5,029 ft).

Natural areas of this next type also make up a large part of the Apennines. They are even smaller and more strictly protected. But this does not mean that you cannot visit them and hike through them.

For example, one of the nature reserves, Monte Catillo (Riserva Naturale Monte Catillo), is just an hour from Rome, just north of the town of Tivoli with its famous villas and other Roman buildings. Paths lead to the reserve directly from the town and its low hills also offer excellent panoramic views of Tivoli itself and the surroundings.

Finally, another popular type of natural area in the Apennines is various individual natural monuments also scattered throughout their territory from Sicily to Genoa. As a rule, these are natural structures of unusual shape or important from a scientific point of view, or rather both.

For example, also here between Rome and Naples, north of the coastal town of Terracina, is the Campo Soriano Natural Monument (Monumento naturale di Campo Soriano)—a huge crown-like rock that was formed in the process of weathering. It is accessible both on foot by trails and by bike. If you use a road bike, like I did, you can see it off the road from about 0.2 km (0.1 mi) but the approach is gravel.

In addition to the natural areas described above, thousands and tens, if not hundreds of thousands, of kilometers (mi) of various long hiking trails wind through the Apennines, many of which are known far beyond the mountain system. To help you get your bearings, I would divide them into three main groups: classical, historical and religious, and culinary—yes, what can you do in Italy without it, a country where food can (and often is) the main goal of a hike, including the longest ones, on which you can have a delicious meal more than once!

Classical hiking trails are routes with a focus on nature and small settlements, which can be of varying degrees of difficulty, but usually involve a higher level of physical activity than the usual walk in the mountains. Some of them are incredibly popular, while others are almost not. Here's what my colleague says again:

A colleague continues: “The mountains of the Apennines have witnessed numerous historical changes. People from all walks of life, from venal mercenaries to valiant conquerors, humble pilgrims, cunning merchants, and just wanderers have been trying to conquer these mountains since the Roman Empire built the roads. Some of those ancient trails still exist and are known for their cultural heritage. The majority of these trails can be walked by hikers of any experience level because they traverse the mountains without significant elevation gain.

Real or not, Italy is well known abroad for the Mediterranean diet. But pizza and pasta is only the tip of the iceberg. Regional varieties and local products are so abundant, that planning your hiking experience and leaving out food escapades would be a huge mistake. Since the Apennine Mountains extend from north to south through many regions, you are likely to find an immense variety of authentic, local mountain products like berries, chestnuts, herbs, dairy products, and rare vegetables.

I would add the Lazio Antiappennines. After hiking in the Aurunci Regional Nature Park or right during it, for example on the Monte delle Fate (1,090 m / 3,576 ft) from the Monte San Biagio train station near the town of Fondi, try the local products of Lazio: pickled olives and olive oil, spinach pie, local “Circeo” sparkling wine, and others. The most famous dessert of the region is Millefoglie, a tort.

For skiing and snowboarding enthusiasts, there are more than 70 ski resorts in the Apennines, which are located throughout the range, but mainly in its northern, central and even southern parts, where you will find most of the resorts, including also the largest of them. It is also the second main area for skiing in Italy after the Alps.

The largest ski resort in the Apennines is Alto Sangro (Roccaraso, and Rivisondoli) with more than 90 km (mi) of slopes and more than 20 ski lifts. It is located in the province of L’Aquila in the Abruzzo region in central Italy in the namesake Abruzzo Apennines at an altitude between 1,309 and 2,141 m (4,294 and 7,024 ft) with a difference of 832 m (2,729 ft). It is the nearest ski resort to the towns of Roccaraso and Rivisondoli in its name, but also to Aremogna. There are no large cities nearby. The resort is best suitable for easy and intermediate skiing—most of its slopes are blue and red. However, for advanced skiers, it has more than 20 km (12 mi) of black slopes each. The most common types of ski lifts are a chairlift and a T-bar. The Alto Sangro season is from early December to early April in general.

Other major areas for skiing in the Apennines with more than 10 km (6 mi) of slopes and more than 5 ski lifts each include the following in descending order of size:

The main ski resort near Rome is Monte Livata—Subiaco-Monna dell'Orso with more than 8 km (5 mi) of slopes and more than 4 ski lifts.

Check the Italy ski resorts map in the World Mountain Lifts section of the site. It includes information about open ski lifts / slopes in Italy in real-time with opening dates and hours. There are also year-round cable cars, funiculars, cog railways, aerial tramways, and all other types of mountain lifts.

Before or after hiking or skiing in the Apennines, visit one of the official tourist offices of this part of Italy. For example, in Pescara, the closest major city to Gran Sasso d'Italia Massif with the highest mountains, which is easily accessible from Rome in just three hours by train, bus or, of course, a car. Also check the official tourism site of Abruzzo region by the link below.

Ufficio IAT Pescara

Piazza della Rinascita

+393316706473

The mountain hut is the main type of accommodation when hiking and skiing in the Apennines, i.e. the same as in the Alps and other mountains. In my experience, unlike the Alps, there are considerably fewer of them in the Apennines, and they are therefore located farther apart from each other. In addition, the level of housing is also generally more simple. In other words, the system of huts in the Apennines is much weaker than in the Alps.

However, even in the more southern Italy, compared to the Alps, you can always find a place to sleep and rest. For example, in the same Gran Sasso and Laga Mountains National Park, these are the following huts: Rifugio Le Fontari, Rifugio Nicola D’arcangelo, Rifugio del Gran Sasso, Rifugio di Lago Racollo, Rifugio Fonte Vetica, Rifugio Orazio Delfico, and many others.

There are also many bivouacs in the Apennines. Hence another important detail: They are often called by the same word, "rifugio", as in the case of the last one in the list above, Orazio Delfico—just a small stone building with a bed inside. So study the map carefully before you go hiking. Or it could be a B&B as in the case of Rifugio del Pellegrino. In short, southern Italians, unlike northern ones, treat the term more loosely.

Another detail: As in northern Italy, the term also does not always mean housing at all, but only a restaurant, as in the case of Rifugio Bar Montecristo. Moreover, they may be open only in tourist season, on weekends, in good weather or holidays, and at other times simply closed. So check their schedules.

In case you have not found a hut or a shelter right in the mountains, you can always stay in dozens of other types of accommodation in towns and villages at the foot of the Apennines. Here I recommend the agriturismos, which are developed all over Italy and combine lodging and a farm restaurant in nature.

The largest cities in the Apennines are the Italian regional capitals: Genova in Liguria, Florence in Tuscany, Rome in Lazio, Naples in Campania, and Palermo in Sicily. I assume you knew them before you read this guide.

The largest city in the heart of the Apennines, the Gran Sasso Massif, is much less known, but I have also already named it—Pescara. But I didn’t tell you that the mountains are visible right from its promenade, or better yet, from the 466 m (1,528 ft) Ponte del Mare (The Sea Bridge), pedestrian and bicycle bridge across the Aterno-Pescara River, which flows here into the Adriatic Sea. It is the main modern architectural landmark of the city, the old part of which hides many historical buildings.

The second main city of this mountainous region, L’Aquila, is located on the opposite side of the massif, but in the valley of the same river. Like in Pescara, Gran Sasso rises over it. In particular, the city is surrounded by a series of peaks with an average height of 2,000 m (6,561 ft): Monte San Franco, Monte Orsello, Monte Ocre, and Cima di Monte Bolza, among others. The city’s main architectural landmarks are the L’Aquila Cathedral and Spanish Fort (yes, built by the Spanish), which today houses the National Museum of Abruzzo (National Museum of Abruzzo—MUNDA), so you have two reasons to visit it.

Do you see where I'm going with this? Similar pairs of cities and resorts on the sea coast and on the hills or mountains can be made literally throughout the peninsula—in other words, in the Apennines and the Antiapennines: Rome—Tivoli, Naples—Caserta, Florence—Lucca, Genova—Cairo Montenotte.

The latter, along with other towns, is interesting because it is located between the Apennines and the Alps, where you can find their exact boundaries. Well, to try.

Explore Apennines with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.

top10

ultra

apennine-2000

italy-ultras

top10

ultra

apennine-2000

italy-ultras

top10

ultra

apennine-2000

italy-ultras

top10

ultra

apennine-2000

italy-ultras

top50

ultra

apennine-2000

italy-ultras

top50

ultra

apennine-2000

italy-ultras