Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

The Regional District of Kootenay Boundary is located in south-central British Columbia, Canada, along the province’s border with the US state of Washington. The region is 8,095 square kilometers (3,126 square miles) in area and the major towns in the region are Trail and Grand Forks. There are 108 named peaks in Kootenay Boundary, the tallest and most prominent of which is Mount Tanner with 2414 m (7,918 ft) of elevation and 1178 m (3,864 ft) of prominence.

The Regional District of Kootenay Boundary is located in the south-central part of the Canadian province of British Columbia.

It borders the Regional District of Central Kootenay to the east and the regional districts of North Okanagan, Central Okanagan, and Okanagan – Similkameen to the west. The major towns within Kootenay Boundary are Trail, which is the regional capital, and Grand Forks, which holds secondary administrative offices for the region.

The primary access roads to the region are Highway 3 ,which runs along the southern end of the district, and Highway 33 which runs north up the middle of the region. The city of Kelowna is located to the northwest of Kootenay Boundary in Central Okanagan and the smaller city of Castlegar in Central Kootenay is located at the southeastern edge of the Kootenay Boundary region.

There are several protected areas in the region that are managed as provincial parks. Additionally, the regional district contains an ecological reserve and a number of recreation sites. The following are the protected areas in Kootenay Boundary:

The geology of the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary is complex. Indeed, the topography of the region is the result of many different factors and events that created the area that we know of today.

About one billion years ago, there was a supercontinent called Rodinia. At this time, North America looked a bit different than it does today because the west coast of Canada ended roughly where the western border of Alberta is currently located. The continent of Rodinia lasted for about 200 million years before the individual continents began to separate from each other.

During the time of Rodinia, the west coast of Canada was butted up against the continent of Antarctica. As North America pulled away from Antarctica, a sea opened between them. This sea eventually filled up with a lot of coarse sedimentary rock, such as gritstone, sandstone, and shale. This divergent plate boundary existed in the same region as the modern Columbia and Rocky Mountains.

The layer of rocks that filled in the rift between the separating continents are referred to as clastic rocks. Clastic layers are made of particles eroded from one place and transported to another by water, gravity, glacial ice, and wind. Basically, these layers are a mixture of rocks from a wide variety of sources. Undersea landslides and glacial erosion were major contributors to the 8 km (4.9 mi) thick clastic layer that makes up part of the Columbia Mountains.

As Rodinia separated, the world had entered into a glacial period, in which much of the Earth was covered in glacial ice. As the glaciers melted, the sea level rose and the clastic layers on the west coast of North America were covered by a shallow sea. With the shallow sea covering the continental shelf, marine sediment began to accumulate over the clastic layer.

About 300 million years ago, the supercontinent of Pangea formed and lasted for about 90 million years. As Pangea broke up, North America began to move westward and it started to override the denser oceanic plates. The oceanic plates had large chains of mostly volcanic islands riding on them, and instead of subducting with the rest of the plate, the islands stuck to the coastal margin of North America where we now find British Columbia.

The force of the collisions built the Canadian Cordillera, which are the mountains of western Canada. First to rise were the Columbia Mountains about 185 million years ago during an event called the Sevier orogeny. The ancient clastic layers that were deposited 800 million years ago were thrust up to form the Monashee Mountains of the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary.

After the Columbia Mountains started forming, the Coast Mountains to the west of the Columbia Mountains began to form from the newly acquired volcanic terranes. Finally, about 80 million years ago, the layers of marine sediment were deformed in an event called the Laramide orogeny which formed the Rocky Mountains.

It is interesting to note, that unlike the Rocky Mountains, the Columbia Mountains have black and white gneiss and granite outcroppings. This is due to the extensive up-thrusting of the basement layers of the continent that didn’t occur in the Rocky Mountains.

The Pleistocene epoch, which started about 2.6 million years ago, brought our most recent glacial period, during which time most of Canada was covered in an ice sheet that was up to three kilometers thick.

These glaciers helped create the topography we now see today by scouring away rock from the landscape. The glaciers created massive valleys as well as moraines, eskers, kames, drumlins, cirques, kettle lakes, and erratic boulder trains.

The ranges that make up the Kootenay Boundary region are subranges of the Columbia Mountains. The Okanagan Highlands are located furthest west in the district. Continuing east are then the Beaverdell Range and then the Monashee Mountains with its subranges: the Midway Range, Christina Range, and the Rossland Range. The southeast corner of the region is the Bonnington Range of the Selkirk Mountains.

There are five distinct ecological zones in the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary, and they are classified according to the characteristic tree species of the zone. The five zones are as follows: Interior Douglas Fir Zone, Interior Cedar-Hemlock Zone, Ponderosa Pine Zone, Montane Spruce Zone, and the Engelmann Spruce-Subalpine Fir Zone.

The Interior Douglas Fir Zone is found within the lowest valleys of the Okanagan Highlands in the Kootenay Boundary region. This ecozone is found in the dry southern interior of British Columbia and it occurs in the rain shadow of the Coast Mountains.

Douglas Fir is the dominant tree species in this zone; however, frequent forest fires have resulted in lodgepole pine stands at higher elevations while ponderosa pine are the seral tree at the lower elevations. Along the dry, western border of the zone, the landscape often becomes savannah-like as it supports meadows of rough fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass.

This zone is prime winter habitat for ungulates, thanks to its low snowpack, abundant shrubs, and old growth Douglas fir forests. Mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, and bighorn sheep all have a preferred habitat within the Interior Douglas Fir Zone.

The Interior Cedar-Hemlock Zone occurs at the mid and lower elevations of the mountain ranges in the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary, within the wet belt of the province. This zone has the widest variety of coniferous tree species of any zone in the province.

Western redcedar and western hemlock are the characteristic trees of the zone; however, white-Engelmann hybrid spruce, subalpine fir, Douglas fir, and lodgepole pine are not uncommon.

This zone is home to some of the most productive forests in British Columbia. There are many animal species that will inhabit the area throughout the summer, such as elk, deer, and bear. However, most animals will leave the area for the lower elevations, which tend to have less snow during the winter months.

The animals that remain over winter in this ecological zone include bears, who hibernate, and animals, such as moose, that have adapted to living in and moving through deep snow.

The Ponderosa Zone is the driest of the forest zones and there are only two small areas in the Kootenay Boundary region that have this ecology. Near the towns of Grand Forks and Midway, the climate is warm and dry enough to support this ecological zone.

Frequent fires create this zone where ponderosa pine is the dominant tree and it maintains widely spaced stands. Bunchgrass is the common understory foliage, and this zone often borders the arid Bunchgrass Ecological Zone. Douglas fir trees are commonly found in the Ponderosa Pine Zone in the cooler and wetter sites.

The short, snow-free winters of this zone make it an important habitat for many wildlife species. The primary ungulates of the region, white-tail deer, mule deer, elk, and bighorn sheep migrate long distances to spend winter in the Ponderosa Pine Zone.

The resident bird species will form larger flocks in this zone than those of the cooler surrounding zones. Clark’s Nutcracker and white-breasted nuthatch feed on large conifer seeds, while the northern flicker and white-headed woodpecker eat insects that live in the bark of pine trees, and others, such as the common poorwill, feed on flying insects.

The Montane Spruce Zone is found at the mid elevations upon the Okanagan Highlands. This zone has cold winters with short, warm summers. Engelmann and hybrid spruce are the most common trees in the zone with some subalpine fir. Where wildfire has destroyed the older forests, there is commonly successional growth of lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, and trembling aspen.

Winter weather and fire are the two major things to which animals must adapt in order to thrive, and the animals of the Montane Spruce Zone are no different.

While the zone is popular with most of the large mammal species of British Columbia, it is only the caribou and the occasional moose that will spend the winter in this zone. These species have adapted to wade easily through the deep snow with their long legs, and the caribou feed off the lichen that grows on the trees.

There are many birds that take advantage of the young forests of this ecological zone and the food that they provide. These include the three-toed woodpecker, black-backed woodpecker, and the pine grosbeak, all of which inhabit pine forests and feed off insects that burrow under the bark of pine trees.

The mature forests in this zone are also an important habitat for many other birds and small mammals, including the fisher, marten, porcupine, great gray owl, red squirrel, southern red-backed vole, and red crossbill.

The Engelmann Spruce-Subalpine Fir Zone occurs at the highest elevations of the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary. This zone is widespread above the valleys in the east of the region, and it is present upon the peaks of the Okanagan Highlands.

The climate in this zone is harsh and often inhospitable. It features cold winters and cool summers, so vegetation and trees in the region must be able to withstand long periods of frozen ground.

Forests of Engelmann spruce, subalpine fir, and lodgepole pine cover the lower elevations of this region. As the elevation of the land increases, the density of the forest in this zone decreases and becomes parkland with open stands of trees interspersed with meadow, heath, and grassland.

This zone is well-suited to support a wide variety of animals. Moose, black bear, and grizzly bear will feed on the abundant spring berries. Elk, bighorn sheep, white-tailed deer, stone sheep, mountain goats, caribou, and mule deer have abundant habitat within this zone. Most mammals will leave this zone during the winter and travel to areas with less snow cover.

The Engelmann Spruce-Subalpine Fir Zone and its old growth forests are also prime habitat for many small mammals and birds. Martens, fishers, and wolverines inhabit the dense forest floor in this ecological zone with gray jays, red crossbill, pine siskin, and Clark’s nutcracker living in the trees. Meanwhile, Columbian ground squirrels and hoary marmots are hunted by golden eagles in the parkland areas of this zone.

It’s estimated that people began to inhabit what is now the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary about 11,000 years ago. The region contains the traditional territory of the Sylix, Sinixt, and Ktunaxa. The Sylix inhabited the Okanagan area in the west of the region, while the Ktunaxa traditionally inhabited the east of the region. The Sinixt had territories that were in the central part of Kootenay Boundary and their territories overlapped with those of the Sylix and Ktunaxa.

The modern Ktunaxa Nation of the Kootenay region are possibly descended from the original group of people that migrated to the region at the end of the Pleistocene glaciation about 11,000 years ago. The Ktunaxa had a territory along the Kootenay River and east over the Rocky Mountains.

During the nineteenth century, the Blackfoot Confederacy pushed the Ktunaxa territory to the west of the mountains as the Blackfoot gained influence and control of the foothills and prairies of southern Alberta. Displaced from some of their traditional territory, the Ktunaxa expanded east and skirmished with the Sinixt over territory.

Both the Sinixt and Sylix are related communities that share similar Salish languages and are considered Interior Salish nations. The Salish culture and language is suspected to have formed from the proto-Salish culture between 3,000 and 6,000 years ago at which time the Salish culture expanded inland from the Pacific coast.

The use of red cedar was common in the Salish culture as it was used to make canoes, longhouses, baskets, mats, clothing, totem poles, and other items. The tradition of carving totem poles was less common to the Salish people than the people of the Pacific Northwest Coast, such as the Haida; however, the Salish did adopt the practice by the twentieth century.

The first European contact with these First Nations was primarily with traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company. However, by the time traders and David Thompson had encountered the First Nations, the horrible effects of smallpox were evident in the region. This was likely due to the epidemic of 1781, which was a major smallpox outbreak that saw mortality rates up to 80%.

With the arrival of the traders, fur trading became a major part of many First Nations’ economies. During the mid-nineteenth century, miners started coming to the region and settlements began to form. As settlers arrived, many First Nations took up farming and ranching in their traditional territory. Currently the region’s economy is dominated by mining, logging, and tourism.

The Regional District of Kootenay Boundary is located among prime wilderness, with incredible scenery, exciting terrain, and plenty of wildlife. As a result, there are many opportunities for outdoor adventure. The following are some of the major hiking locations and attractions in the district.

Granby Provincial Park is a long, narrow, forested drainage into the Granby River, which is the division between the Christina Range and the Midway Range of the Monashee Mountains. Covering 408 square kilometers (157 square miles) of rolling ridges and mountain tops, there are plenty of ways to enjoy the wilderness of the park during your visit.

Some of the ways to enjoy the park are by hiking, mountain biking, and horseback riding. Hunting and fishing are permitted in the park and there are many opportunities for wildlife viewing, and it is an important area within the region’s grizzly bear habitat.

Winter recreation opportunities include ski touring, snowshoeing, and snowmobiling. There are many areas within the park that are popular with snowmobilers and there are outfitters that offer snowmobile tours, too.

The north end of the park contains remnants of mines from the 1800s, while the whole park contains spaces that were used by First Nations. One of the primary indicators of First Nations use of the region are the “culturally modified trees.” These are trees that were used for traditional purposes of the First Nations and are often found as trees with strips of bark peeled away, or tool marks from harvesting the tree.

Major trails in the park include the Granby River Trail, Height of Land Route, Mt. Young Cabin Trail, Arthurs Lake Trail, Bluejoint Lookout Trail, and Rawhide Trail. These trails lead to mountain summits and many follow trails that were used by miners in the 1800s. All the trails will bring you close to nature and give you fantastic views.

Gladstone Provincial Park encompasses 394 square kilometers (152 square miles) on the north end of Christina Lake, which has a reputation as one of the warmest and clearest lakes in Canada. With the Texas Creek campground, pocket sandy beaches, wilderness trails, and cultural sites, Gladstone Provincial Park is an incredible destination.

The park contains cedar and hemlock forests inhabited by a variety of wildlife, including deer, elk, California bighorn sheep, and grizzly bear. The lake provides critical spawning habitat for kokanee and rainbow trout.

Gladstone Provincial Park’s cultural sites include shoreline pictograph sites and evidence of First Nations communities. There are historic trails, a semi-permanent village, historic home sites, and an area where fish may have been caught and processed. Alongside Benninger Creek, there are remnants of more modern history with a historic cabin and an old gold mine to encounter.

There are many trails in the park that lead to summits, beaches, and historic sites. The following are some of the popular trails: Deer Point Trail to Troy Creek, Xenia Lake Trail, Sadner Creek Trail, Mount Faith Trail, Mount Gladstone Trail, and Peter Lake Trail.

The Regional District of Kootenay Boundary covers an extensive wilderness area that is used for mining, logging, and recreation. There are many places around the region with a rich local culture and history. The following are several places to stay as you explore the region.

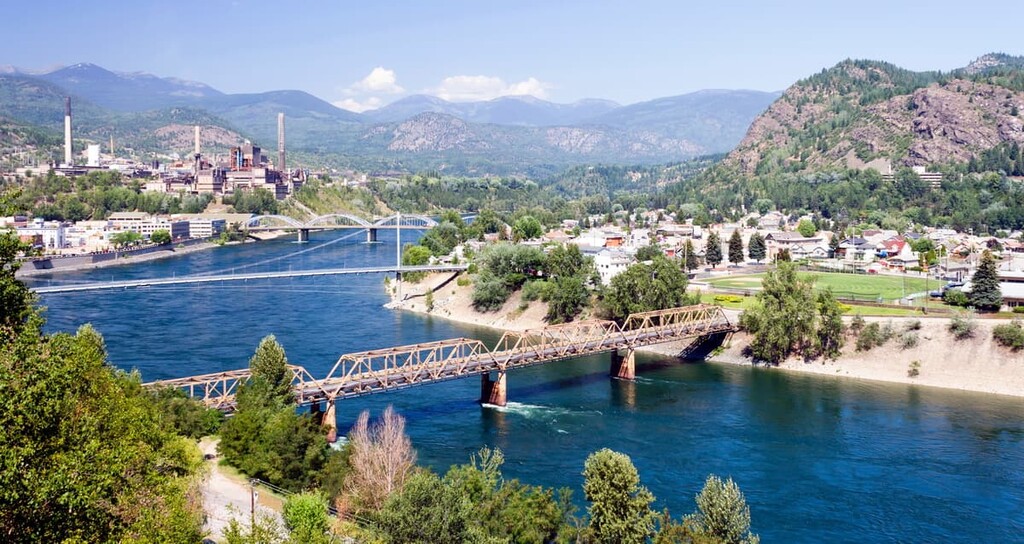

Incorporated as a city in 1901, Trail was named after the Dewdney Trail that once passed through the area. The Dewdney Trail was a trail that roughly paralleled the Canada – US border tying together the early mining settlements of the British Colony of British Columbia to prevent US intrusion into the region.

Located along both banks of the Columbia River is southeast British Columbia, Trail has many attractions and hikes for visitors to enjoy. This includes Beaver Creek Provincial Park, the Columbia River Skywalk, and many museums and art galleries.

Castlegar is a community in Central Kootenay that’s located at the edge of Kootenay Boundary. The city is situated in the Selkirk Mountains at the confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers. In September of 1811, David Thompson camped at the area that would later become Castlegar.

Like many of the settlements in the Kootenay region, Castlegar started as a settlement for miners as they searched for gold. The city has a rich history based in the mining and forestry activities of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as well as a historical place for the First Nations of the region—the Sinixt and Ktunaxa.

Some of the major attractions in Castlegar, aside from its access to incredible wilderness areas, are the Doukhobor Discovery Centre, Kootenay Gallery, and Zuckerberg Island Park.

Established in 1963, Big White Ski Resort is located on the eastern slopes of Big White Mountain, some 56 km (35 mi) to the southeast of Kelowna, British Columbia. Big White is the third largest resort in British Columbia and it is one of the best ski resorts in Canada.

There are several terrain areas on the mountain offering winter activities from skiing, terrain parks, a tubing park, and incredible mountain biking in the summer. There is a range of accommodation options offered at the resort, including hotels, condos, vacation homes, and a hostel. Many of the accommodations are hillside, allowing you to ski or bike to and from your doorstep.

The city of Kelowna, British Columbia spans across Okanagan Lake and is located west of the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary. There are many lakeside accommodations, campgrounds, and hotels to stay at while visiting the region.

Kelowna is a popular destination with its proximity to Okanagan Lake, sandy beaches, countless orchards, warm weather, and a relaxed atmosphere. There are fantastic restaurants in the city that are run by local First Nations, as well as scenic golf courses, fishing, waterskiing, farmers markets, and an unusually large number of restored antique and vintage cars driving around the city.

With hot summer weather and mild winters, there are year-round outdoor adventures to be had in Kelowna. Along with the fun water-based activities on the lake, there are countless trails that take you along the lake, through the hills, along ridges, and up to the tops of the many peaks in the area.

Explore Regional District of Kootenay Boundary with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.