Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

The Western Development Region is a large, mountainous region of Nepal surrounding the city of Pokhara. It includes three of the world’s fourteen 8,000 m peaks: Dhaulagiri I (8,167 m / 26,795 ft), Manaslu (8,163 m / 26,781 ft), and Annapurna I (8,091 m / 26,545 ft), as well as one of the deepest canyons on Earth, the Gandaki River Gorge. The region encompasses some of the most scenic vistas in the Himalayas and some of the best hiking in Nepal. The trekking includes both simple hikes for beginners and long journeys into some of the most remote areas in the world. The region is also home to the lowland city of Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha, as well as the Upper Mustang Region, a culturally Tibetan area only opened to public access in 1992. The region's highest and most prominent peak is Dhaulagiri I (8,167 m/ 26,795 ft).

In general, the Himalayas are jam-packed with some of the most beautiful vistas on earth, diverse human cultures, and unique wildlife, and the Western Development Region is no exception.

For starters, it’s important to note that the Western Development Region is no longer in use. After the 2015 earthquake, the area was reorganized into provinces. Today, it is located in Gandaki and Lumbini Provinces. However, the former regional boundary is still frequently mentioned in discussions about travel, hiking, and other outdoor recreation.

The Western Development Region contains three of the world’s fourteen 8,000-meter giants, plus a host of six- and seven-thousand-meter peaks.

The terrain rapidly rises as you travel south to north. From Pokhara to the Annapurna Conservation Area, the elevation increases thousands of meters over just 30 km. The massive relief creates some of the area’s most dramatic features, like the Gandaki River Gorge, the deepest canyon on Earth.

This canyon is walled in on one side by Dhaulagiri I, the region's western boundary. Further to the east are two main ranges: the Annapurna Massif and Mansiri Himal. These center around Annapurna I and Manaslu and include most of the major hiking routes in the area. As the region’s highest peak, Dhaulagiri is also noteworthy but is less frequented by trekkers.

North of the Annapurna and Manaslu groups, elevation tapers. The climate dries significantly, becoming a high desert. Following the Gandaki Gorge north toward China, you enter the Mustang district, an area defined by high, winding canyons that make transport challenging. The district is one of Nepal's most remote, making it a coveted destination for adventurous hikers.

The Western Development Region's most notable feature is its three 8,000-meter peaks. Each massif dominates a vast subrange of mountains, defining the skyline for hundreds of kilometers.

Dhaulagiri is the seventh-highest mountain on earth and the highest in the Western Development Region. Its name means “white mountain” in Sanskrit. It was the second-to-last 8,000-er to be summited in 1960. It is also the second deadliest 8,000-er in terms of total climbers who have died attempting to summit. Climbers typically ascend by way of the Northeast Ridge, approaching from the canyon to the west of the summit.

Dhaulagiri also has a shocking vertical rise. Its eastern face starts at the bottom of the Gandaki Gorge and rises 7,000 m to the summit, providing the relief that technically makes Gandaki Gorge the deepest canyon on earth. The Northeast Ridge also encloses a separate area - the Dolpo Region, one of Nepal's most unique and isolated places.

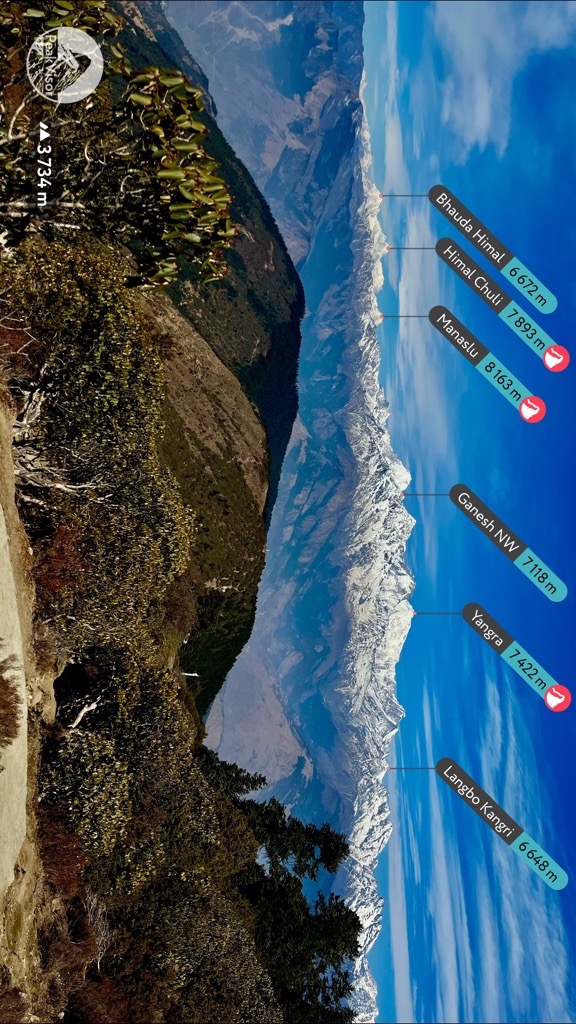

Manaslu (also called Kutang) casts a striking silhouette. It is the eighth-highest mountain on earth and the high point of Mansiri Himal, a subrange north of Kathmandu. The mountain’s profile is split between two summits, creating a menacing, jagged shape. The twin summits roll down along well-defined ridges. The most prominent of these is the south ridge, which connects Manaslu to Ngadi Chuli (7,613 m / 24,977 ft) and Himal Chuli (7,893 m / 25,896 ft), the 5th highest 7,000 m peak.

The most common approach is to climb the Northeast Face, which is the most straightforward. However, many other approaches vary significantly in difficulty; the South Ridge was considered one of the most challenging mountaineering problems in the world when it was first climbed in 1984. Recent data shows that Manaslu’s summit is at a different point than previously thought, and many climbers have returned to reclaim the true summit.

Annapurna was the first 8,000 m peak to see an ascent when Maurice Herzog’s team of Chamoniards famously claimed the summit in 1950. The ascent is documented in an eponymously titled book, Annapurna, which remains one of the mountaineering world’s most influential publications. It is Earth’s 10th-highest and the most dangerous 8,000-er by summit-to-death ratio; for every 100 successful ascents of Annapurna, more than 31 climbers have died.

Even adjusting only for climbs since 1990, the ratio remains high at 27. Almost one in 20 climbers attempting Annapurna have died trying, due partly to the route, which is very technical and includes extended glacier travel and serac exposure. But it is also due to the area’s weather, which is notoriously unpredictable. Additional hazards include high avalanche risk and nearly constant rockfall.

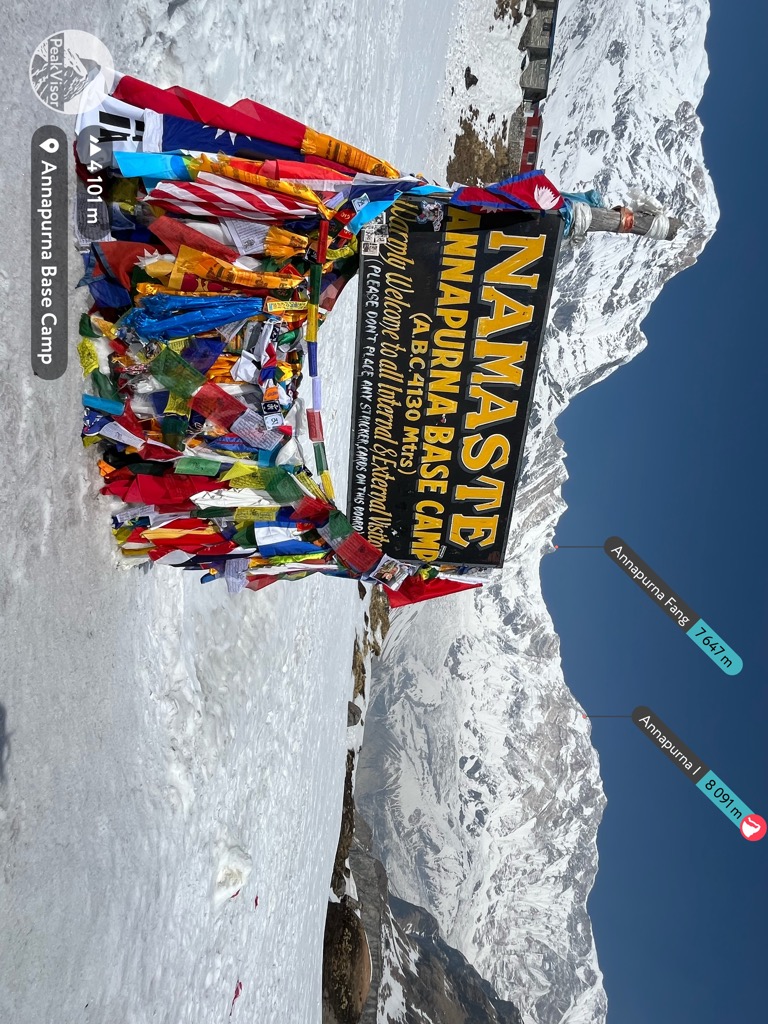

Annapurna sits in an immense basin walled in by gigantic peaks called the Annapurna Sanctuary. Almost every mountain along this circular ridge sits above 7,000 m, including Annapurna III (7,555 m / 24,787 ft), Annapurna South (7,219 m / 23,684 ft), Gangapurna (7,455 m / 24,459 ft), Khangsar Kang (7,485 m / 24,557 ft), and the Annapurna Fang (7,647 m / 25,089 ft).

Machapuchre (6,993 m / 22,943 ft), also called The Fishtail, sits above the sanctuary's entrance as if guarding its secrets. It is Nepal's highest 6,000-meter peak and one of the country’s most recognizable mountains for its unbelievable vertical relief and sinister silhouette.

Transport is the single biggest challenge when visiting Nepal. The 2015 earthquake destroyed and damaged infrastructure throughout the country. Nevertheless, even before the quake, roadways were subpar. The Nepalese are in a constant battle against landslides and extreme erosion, primarily due to the intense monsoon season from mid-May to late July.

Even the major highways in the country have long stretches of rough, unpaved surfaces. Backroads are almost always dirt and usually require high clearance.

As a result, getting anywhere in Nepal is either time-consuming or expensive. In most cases, the fastest (and most expensive) option is to fly. For example, you can get to Pokhara from Kathmandu either by a ten-hour bus or by a one-hour flight. The difference in cost is about $125 (16,600 Nepalese rupees).

In some cases, there’s just no winning. Even a luxury bus or a taxi can’t fix the road. But there are a few things that can help.

Depending on where you’re going in the Western Development Region, you will start from Pokhara or Kathmandu. The Annapurna Conservation Area, which includes the Annapurna Circuit and Basecamp, is just north of Pokhara. Mansiri Himal is easier to get to from Kathmandu.

There are plenty of buses, taxis, and Jeeps to get you where you need to go in Nepal. But haggling is imperative if you don’t want to be gouged. Additionally, apps like InDrive and Pathao help cover short distances within major cities.

If you’re not flying between cities, the best option is to take a tourist bus. These are much more comfortable than local buses and only cost a little extra. Taxis and jeeps are much more expensive and are neither faster nor more comfortable. Tourist buses to Pokhara depart from the Tourist Bus Stop on the north end of Thamel in Kathmandu. Buses from Pokhara leave from the east end of Lakeside near the ACAP permit office.

The tricky part is getting to and from the trailheads. Bus routes are limited to more urban towns with better roads. Taxis and jeeps will take you much further faster, but they’re usually expensive; this is where traveling in a group is handy. Jeeps typically have a fixed rate you can split between your group or other travelers. Beyond that, your best bet is to haggle (within reason). When negotiating, drivers usually start the price 25-75% higher than they are willing to accept.

The Himalayas are one of the greatest showcases of Earth’s geology. They span a vast area across South and Central Asia, primarily China, India, Bhutan, and Nepal. They are a landscape of extremes. Extensive glaciation and the world’s strongest monsoon constantly shape high summits and deep valleys.

The force of erosion has created immense landforms across the Himalayas. The range has the highest concentration of glaciers and icefalls outside the Arctic polar regions and is often called the “third pole.” The largest icefall on earth, the Khumbu Icefall, sits just above Everest Base Camp. Glaciation creates deep, winding canyons, which make up the majority of the livable area in Nepal. These are deepened by frequent and intense rainfall and landslides.

The most notable canyon in the area is the Kali Gandaki Gorge, which cuts through the western side of the Western Development Region. The Gandaki Gorge runs roughly 106 km (66 mi) and is roughly 20-30 km (12-19 mi) wide on average. The south end begins just north of Baglung in Nepal and continues north through the Mustang District into Tibet.

Canyons are famously hard to measure. Ideas like “depth” and “volume” of a canyon become more nebulous under a microscope. But if the canyon's depth is determined from the high points of Annapurna and Dhaulagiri on either rim to the river bottom between, the Gandaki is by far the deepest canyon on earth.

Geologically, the Himalayas are still very young and growing rapidly. As the Indian landmass converges with the Eurasian tectonic plate, the mountains grow around one centimeter annually, making the Himalayas the fastest-growing mountains on earth. In just 55 million years since the Indian landmass collided with Asia, the mountains have risen nine kilometers. As a result, the majority of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks and about half of the world’s 7,000-meter peaks are in this one chain (with the remaining 8,000-ers located in the neighboring Karakoram).

The ecosystems of the Himalayas are surprisingly diverse. The range covers enormous elevation, and precipitation differs starkly from the south to north slopes. Just within the Western Development Region, you can find eight distinct ecoregions.

The lowlands on the south side of the mountains are generally green and forested. Because the summer monsoon approaches from the south, the precipitation falls along the Himalayas’ southern slopes rather than the northern ones. These areas feature grassland, subtropical forests, and even some subtropical pine forests. The grasslands are most famous for their Indian rhinoceroses. Most people don’t associate Nepal with “jungle,” but the foothills of the Himalayas are full of dense bamboo forests and tall deciduous trees. These lush mixed forests are prime habitats for much wildlife, including monkeys, monals, red pandas, and fruit bats.

Continuing higher, forests become more temperate, with a mix of deciduous and coniferous trees. Higher still, conifers take over entirely. Temperate forests are good places to watch for birds. There are 915 recorded species of birds in Nepal, with everything from flamingos to kingfishers to eagles. Mammals like moon bears also spend most of their time in these higher forests.

Higher still, we arrive above the treeline. Trees typically start to thin and disappear around 4,000 m (13,123 ft) in the Himalayas. However, some of the region’s most important animals live in the grasslands above the treeline. These include yaks and large predators like the Himalayan wolf. There are also many elusive cats in the upper forests and grasslands above the timberline, including snow leopards, clouded leopards, and Pallas’s cats.

Above this, plants give way to a world of rock and ice. At a certain point, the conditions become so inhospitable that nothing can survive. The high alpine is like an ecological wasteland, with few full-time residents.

Dropping off the summits and continuing north, the mountains are much drier. The Mustang Region is ecologically similar to Tibet, with large areas of dry, shrubby steppe. These harsh landscapes are dry, cold, and vast. Unsurprisingly, they cater to animals that can cover large distances. Birds of prey and grazers like the kiang, a wild donkey, do well here.

The Western Development Region includes some of the most important places in both religious and mountaineering history. First and foremost is Lumbini, the birthplace of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. The Buddha was born around 2,600 years ago as a prince. He famously renounced his family, home, and wealth to pursue enlightenment as a monk. His teachings gave birth to Buddhism.

Buddhism is now a minority religion in Nepal, with 80% of Nepalese identifying as Hindu and the remaining 20% as Tibetan Buddhists. Tibetan Buddhism arose around 1,300 years after the Buddha’s death when the religion had already traveled to every other corner of Asia. It is the youngest form of Buddhism, made famous in large part by the life and teachings of the Dalai Lama. In a sense, Buddhism began in Nepal. In another, Buddhism took the longest path possible to return to Nepal.

Much later, Westerners took an interest in Nepal and the Himalayas. During the Enlightenment, Europeans saw the aesthetic value of nature and started exploring mountains for sport. By the mid-1800s, all of the most significant peaks in the Alps had been summited, and climbers began looking elsewhere for higher, more challenging summits. Europeans visited the Americas and Africa, pushing ever higher in the Rockies and Andes ranges.

The Himalayas were regarded as the “last frontier” in mountaineering. Several attempts to climb an 8,000-meter peak in the late 1800s, including the first attempt on Nanga Parbat in 1895, failed. It was not until 50 years later that Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal completed the first ascent of Annapurna.

The team had initially set out to climb Dhaulagiri but decided immediately that the peak was “unclimbable.” They instead turned east, crossed the Kali Gandaki Gorge, and approached Annapurna via the north face. Their route passed through areas of extreme avalanche danger, but they were lucky and reached the summit on June 3rd, 1950.

Three years later, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay would complete the first ascent of Mt. Everest (8,848 m / 29,029 ft). At this point, the inherent goal of mountaineering, to “go higher,” was over. Nevertheless, the sport continued to push the limits with more technical and faster ascents than ever, propelled by advancements in gear, technology, fitness, technique, and knowledge.

Other 8,000-meter peaks in the Western Development Region weren’t climbed for several more years. Manaslu was completed in 1956 by a Japanese and Nepalese team. Dhaulagiri resisted attempts until 1960, when a team of Europeans and Nepalese finally reached the summit; it was the last 8,000-meter peak to be climbed.

Despite the climbing world’s attempts to conquer every high point, there are still unclimbed peaks in the region. One example is Machapuchare, the “Fishtail,” which is sacred to the Gurung people. The Nepalese government does not allow permits to climb the peak, meaning that, at least officially, it will probably remain unclimbed forever.

There are three main trekking zones in the Western Development Region: The Annapurna Range, the Upper Mustang, and the Mansiri Himal. Depending on your objectives, you may need several permits for each area. The rules change regularly, but this information is accurate to 2024.

The Annapurna Range probably has the most options of these three. It includes several short trails and one long circuit. All of them are popular and usually busy during the high season. The Upper Mustang is more involved and remote, although the trail is a much lower elevation on average.

Both areas are inside the Annapurna Conservation Area, which requires a single-entry permit (3,000 rupees or about USD 22). Beyond that, the Upper Mustang sits in a restricted area with an additional permit, which costs a whopping $500 (66,600 rupees) for the first ten days.

The other permit you may need is the TIMS (Trekkers’ Information Management Systems) card. You only need a TIMS card if you are hiking with a guide. Guides are mandatory on some trails (most circuits and treks longer than seven days). More details on this are below.

If you are going unguided, you only need the Annapurna Conservation Area Permit (ACAP). You can get one at the permit office in Pokhara, on the east end of Lakeside. Bring two passport photos and your passport. If you’re going with a guide, they should be able to work out all of the permits for you.

In Mansiri Himal, things get a little more complicated. The most popular route here is the Manaslu Circuit, which is seeing more traffic due to its well-preserved trail. By contrast, most of the Annapurna Circuit has been replaced with a noisy, dusty road.

To do the Manaslu Circuit, you’ll need a permit for the Manaslu Conservation Area (MCA), a permit for a restricted area inside the MCA, which preserves several towns along the way, and an ACAP as the route passes through the ACA on the way back.

The bad news is that this all adds up. You’ll spend about $125-150 (16,600-20,000 rupees) just for permits. The good news is that you won’t have to do this yourself; your guide will handle permit acquisition for you.

The last major logistical point is lodging. Fortunately, accommodations are one of the best parts of trekking in Nepal - all major trails are full of guest houses. These cozy lodges make planning much easier. They normally have comfortable beds with warm blankets for very cheap ($3-7 or 500-1000 rupees per night, depending on where you are). Prices in the Annapurna Conservation Area are fixed and non-negotiable.

Bear in mind that if you stay in a guesthouse, you’re expected to order food, as this is how they actually turn a profit. Meals are reasonable, usually $3-7. If you have a hearty appetite, order dal bhat, Nepal’s national dish. It’s a cheap meal, and it’s customarily served all-you-can-eat.

When budgeting, plan anywhere from $18-30 (2,500-4,000 rupees) per day for meals and accommodation, depending on how much you eat. Bringing trail snacks, coffee, and tea from the city will save you money.

The Annapurna Range is one of the most popular destinations in Nepal. It includes several short but sweet treks that appeal to beginners, as well as a few longer routes.

If this is your first time doing a multi-day trek, it’s wise to start small. Poon Hill (3,210 m / 10,531 ft) is a quick route that only takes three to four days. It also doesn’t require a guide, which appeals to budget-minded backpackers. The route begins with a bus or taxi ride from Pokhara to Birethani. Hike to Ghorepani, then Poon Hill summit. While this is far from the most impressive summit in Nepal, the views are spectacular; you can see two 8,000-meter peaks - Annapurna and Dhaulagiri - on either side of the Gandaki Gorge.

The return cuts east through Tadepani. At this point, you can either head back to the trailhead through Ghandruk or continue up the canyon to ABC (Annapurna Base Camp). People regularly chain these objectives together. Combining the routes takes eight to ten days.

Annapurna Base Camp is a journey into the heart of the Himalayas through a scenic canyon to the Annapurna Sanctuary, with no guide required. You’ll have views of Machapuchare and Annapurna South for days as you approach the upper basin. The route takes five to eight days, depending on your fitness.

Similar to Poon Hill, start by taking the bus from Pokhara to Birethani. You can catch a local bus at Baglung Bus Park in Pokhara. From Birethani, take a taxi to Kimche. The road is often out in this area, so how far you make it by car depends on road conditions. From there, hike to Ghandruk.

The route continues directly up the canyon. Be wary of seasonal avalanche closures on the west side of the canyon, particularly in the spring months. Passing through Machapuchare Base Camp, you’ll be treated to one of the best views in Nepal.

For the return trip, you can either return how you came or make your way down to Jhinu Danda, turning east in Chomrong and heading downhill. Jeeps for hire in Jhinu can take you directly back to Pokhara. They typically seat eight people and cost 5-6,000 rupees.

Mardi Himal is less busy than the other two short treks in the Annapurna Range. It takes five to eight days to complete and affords excellent views of the Annapurna Sanctuary. Like Poon Hill and Annapurna Base Camp, you can do it without a guide.

From Pokhara, take a bus or taxi to Kande. Then head north (uphill) through Australian Camp to Deurali. The route continues north through Forest Camp, Low Camp, and High Camp. You’ll hike along a high ridge, which is both exhausting and exhilarating. Be prepared for a lot of elevation gain. Finally, you’ll top out at Mardi Himal Base Camp (4,224 m / 13,858 ft).

The return route follows the high ridge to Low Camp, then turns east downhill to Sidhing Village and Lumre, where you can catch a bus back to town.

The Annapurna Circuit is a significant objective. It takes a lot of muscle, time, and money. The route circumnavigates the entire Annapurna Range. Depending on how much of it you drive, it involves 160-230 km (99-143 mi) of hiking.

Much of the trail's first half was recently converted to a roadway. The development has generally been seen as a bad thing, as the new road is dusty, loud, and full of traffic. But the upside is you don't have to commit to hiking as much; you can take a Jeep past the old trailhead and start the hike much higher.

Hikers typically start the Annapurna Circuit from Kathmandu. You will take a bus/Jeep to Beisahar and begin the slow march uphill, heading north and then west through one of the largest canyons in Nepal. This is the section now covered in road, which has started to drive more and more hikers to take on the Manaslu Circuit instead of the Annapurna Circuit. If pressed for time, you can technically hire a jeep to take you as far as Manang, which is all the way on the north side of the Annapurna Sanctuary.

From here, the route proceeds north over Thorong La Pass (5,420 m / 17,769 ft), the trail's high point. This part of the trek includes some glacier travel and extended snow/ice hiking. You’ll be glad you hired a guide once you arrive.

Then, proceed back downhill, heading west through Jomsom and turning south through Tadepani to Nayapul. This route takes anywhere from 14 to 21 days in total, depending on fitness and how much of the road you bypass by driving.

The vast majority of hikers come to Mansiri Himal for one reason: the Manaslu Circuit. As I mentioned, this trail has grown in popularity since the new road was built along the Annapurna Circuit. It’s a long, moderate-to-strenuous trek that requires a guide, requires a similar time commitment, and tops out at a similar elevation. The main benefit is that it’s much more remote and well-preserved than the Annapurna Circuit.

This trek begins in a well-preserved area between two of Nepal’s most imposing peaks. After driving from Kathmandu to Soti Khola, the trail heads up a massive canyon separating Manaslu from Yangra (7,422 m / 24,350 ft), also called Ganesh I. The following ten days are a long ascent around the backside of Mansiri Himal, within a stone’s throw of Tibet.

The high point of the trek is Larkya La Pass (5,106m / 16,752 ft), one of the longest in the Himalayas. It’s a treacherous stretch covered in permanent snowfields and glaciers. After the pass, the trail descends quickly to Dharapani at just 1,860 m (6,102 ft). From here, it’s mostly flat hiking to Besi Sahar and a long Jeep ride back to Kathmandu.

The Upper Mustang is neither the highest nor the most technical trek in Nepal. Instead, it offers an opportunity to see one of the most remote places in the Himalayas, full of ancient culture and inspirational scenery. Until 1992, this area was the Kingdom of Lo and was completely closed off to the rest of the world. The entire region is a high desert and looks more like Tibet than the rest of Nepal. The local peoples all speak Tibetan languages and only had contact with the outside world as of 30 or so years ago.

To begin, most parties will fly from Pokhara to Jomsom. This is the main hub at the south end of the Mustang Valley. From here, the route proceeds north through Kagbeni and Syanbochen. In general, the trail sits between 3,500-4,000 meters (11,483-13,123 ft). Continuing up, you will pass through Tsarang before arriving at Lo Manthang, the former capital of the Kingdom of Lo. The route doubles back and returns the same way, although some parties will head east and make a loop back to Jomsom.

There are few major cities in Nepal. Because the country mainly comprises narrow river valleys, there just aren’t many places large enough to support urban sprawl. In terms of getting around, there are just a few hubs with airports and bus stations you should know about.

Pokhara is the largest city in the Western Development Region, with 600,000 people. It’s also the locals’ favorite. The Lakeside district features excellent restaurants and even some upscale lodging. If you’re headed to the Annapurna Range, you will probably pass through Pokhara at some point. The city has an airport that can get you quickly to Kathmandu, Lumbini, and Jomsom. There are two main bus stations: Baglung, where buses depart for nearby towns, and the Tourist Bus Park, which services Kathmandu.

Lumbini is the famous birthplace of Siddhartha Gotama, the Buddha. Every year, thousands of visitors pilgrimage to Buddhism's birthplace. It’s one of the most important places in the Western Development Region, but it’s a relatively small village with a few temples and holy sites. The nearest airport is in Siddhartha Nagar, about 22 km away. You can also take a bus to Lumbini from Pokhara or Kathmandu.

Kathmandu is Nepal's capital and largest city (population of 856,000). It isn’t in the Western Development Region, but chances are you will have to pass through it to get where you’re going. The city is loud, busy, and remarkably polluted due to the fact that it sits in a large valley surrounded by some of the world’s tallest peaks. Pollution becomes trapped as cold air from the mountain sinks into the valley. The city can be exciting, but overall, it’s not what most Western visitors are looking for, and it mainly serves as a transportation hub.

The central tourist district, Thamel, features many outdoor gear stores where you can find all kinds of affordable hiking and climbing gear. Be aware that most garments you see in Thamel are Chinese counterfeits. But the quality is still high, especially considering the low cost of things like rain jackets and pants.

You can hire a taxi to the city center from the airport or take the green bus from in front of the airport to Ratna Park, about ten minutes from Thamel. The Tourist Bus Stand, where buses to Pokhara stop, is on the north end of Thamel. Other buses depart from Gongabu Bus Park.

Explore Western Development Region with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.