Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Nestled in the heart of the Northeastern USA states of New Hampshire and Maine, the White Mountains are one of the most ruggedly beautiful mountain ranges of the US’s eastern seaboard. Home to densely packed conifer trees and tall granite cliffs, the White Mountains are an outdoor enthusiast’s paradise for hiking, skiing, climbing, and a whole host of other adventure pursuits.

There are 733 named mountains in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The highest and most prominent of these mountains is Mount Washington, which stands at a respectable 6,288 feet (1,917 meters), making it the tallest peak in the Northeastern United States. While the peaks of the White Mountains don’t manage to break the 6,500 ft (1,981m) barrier, they are home to some of the most difficult hiking terrain and worst weather in the continental United States.

The mountains themselves cover approximately one-quarter of all of New Hampshire’s total land area, and a small portion of the western edge of Maine. They are close to the northern terminus of the larger Appalachian Mountain range and are known for their challenging terrain.

Geologists believe that the White Mountains were formed by magma intrusions approximately 124 to 100 million years ago as the North American Plate traveled westward over a location then known as the New England hotspot. These magma intrusions left behind the granitic mountains and cliffs that gave New Hampshire its nickname, “The Granite State.”

Hundreds of millions of years after the mountains were first formed, they experienced widespread glaciation, which, for the most part, rounded over their peaks and carved out the huge U-shaped valleys of the White Mountains. Today, these U-shaped valleys are affectionately known as “notches,” and include the famous Pinkham Notch and Franconia Notch in the northern parts of the range. Further evidence of this glaciation is found in the glacially-carved cirques that form the backcountry skier’s paradise of Tuckerman’s Ravine on Mount Washington and the King Ravine on Mount Adams.

The vast majority of the White Mountains are part of the White Mountain National Forest, in addition to a number of smaller state parks. All of this is good news to outdoor enthusiasts, who have plentiful access to the range’s many peaks on a fantastic network of well-maintained trails. The White Mountains also feature a system of alpine huts that are owned and operated by the Appalachian Mountain Club for use by hikers who want a more comfortable mountain experience.

These days, the White Mountains are the go-to destination for outdoor enthusiasts from the greater Boston, Massachusetts region, who flock to the area to enjoy the region’s many trails, ski resorts, and tax-free shopping. Whether you stick to the trails or take the path less traveled, the White Mountains are a fantastic place to explore and get outside.

Most of the White Mountains lie within the White Mountain National Forest, which is managed and operated by the US Forest Service. Although the motto of the US Forest Service is “The Land of Many Uses” - a nod to the Service’s propensity for leasing land for mining and logging exploits - the sheer popularity of the region as a prime place outdoor recreation, means it’s one of the best National Forests in the entire country for human-powered outdoor pursuits.

There are so many different places to hike within the White Mountains that the easiest way to conceptualize the range is to break it up into smaller “hiking areas.” There are a few different hiking areas within the National Forest, itself, as well as some others that lie within some of the smaller state parks in the region.

Pinkham Notch is one of the most famous areas in the White Mountain Range as it forms a fantastic pass between two of the largest subranges in the region. The Notch was carved out by the Laurentide ice sheet during the Wisconsinian Glaciation, which formed the U-shaped valley that we see today.

The two main hiking areas within close proximity to Pinkham Notch are the Presidential Range, to the west, and the Carter-Moriah Range to the East. The Ellis River (a tributary of the Saco River) and the Peabody River (a tributary of the Androscoggin River) drain from the Notch, which tends to see some fairly harsh weather. The most popular of these areas is the Presidential Range, so we’ll take a look at that here.

The Presidential Range got its somewhat odd name because the most prominent peaks in the area are all named after US presidents and other important figures from the 18th and 19th centuries. The most prominent peak in the range is the 6288ft (1917m) Mount Washington, which was named after the US’ first president.

Mountains in the range were originally given names of presidents in the order of their heights, with the tallest mountain being named after the first president (Washington) and the second tallest being named after the second president (Adams). Unfortunately, an early surveying error incorrectly calculated that Mount Madison (named after the fourth president) was taller than Mount Monroe (named after the fifth president), when actually, Mount Monroe is 22ft (6.7m) taller. Tradition won out in that battle and the peak names stuck, even though they’re not quite in the correct order.

Mount Jefferson (left), Mount Adams (middle), and Mount Madison

Before venturing out into the Presidential Range, however, it’s important to know that this area of the White Mountains consistently has some of the worst weather in the Eastern United States. In fact, on April 12, 1934, the Mount Washington Observatory (the weather station at the mountain’s summit) recorded a wind speed of 231 mph (372 km/h). Although that record has been superseded by other wind speeds, the mountain still holds the world record for the highest wind speed on Earth that occurred without the help of a tornado or cyclone.

The Presidential Range itself is approximately 19mi (31km long and encompasses over 8,500ft (2,600m) of elevation gain, all of which is hikeable as a single-day traverse in the summer and by very experienced winter mountaineers. The Presidential Range Traverse is one of the most challenging single-day hikes in the White Mountains, so many people choose to complete it over the course of a couple of days. The hike takes people up and over every major summit in the range, which is no easy feat. Some of the more daring among us try to do the traverse twice in a single day.

The jewel in the crown of the Presidential Range is, of course, its highest peak - Mount Washington. Although there are two ways up the mountain that require minimal human effort (the Cog Railway and the Auto Road), outdoor enthusiasts usually opt for an ascent of one of the Mountain’s many trails.

Mount Washington cog railway

In the summertime, the Tuckerman (Tux) Ravine Trail is the most popular route to the top as it sneaks its way up the easiest terrain on the mountain. The Lion Head Trail is approximately the same length as the Tux Ravine Trail, but rewards hikers who take on its steeper terrain with better views. Hikers who really want to get away from the crowds in good weather will opt for the Boott Spur Trail, which provides excellent views, though it is a bit longer than the alternatives.

Winter adventurers at Mount Washington tend to find themselves in one of three parties: hikers who want to bag a challenging winter summit, skiers who want to shred some of the best backcountry skiing in the east, and mountaineers who challenge themselves on one of the mountains many ice-filled gullies. Hiking on Mount Washington (or anywhere else in the Whites, for that matter) in the winter involves special skill and equipment to effectively manage risk.

Hikers who are prepared for the challenges of winter on Mount Washington can challenge themselves to make their way up one of the peak’s winter trails. Perhaps the best-known winter hiker’s route on the mountain is the Winter Lion Head Trail, which, while sharing a name with the Summer version of the trail, actually takes a slightly different path to avoid a section of avalanche terrain. Hikers that want even more of a challenge can attempt a Presidential Range Traverse in the winter, which takes most experienced hikers a few days to complete.

If seclusion and rugged terrain with stunning views are what you seek, look no further than the Pemigewasset Wilderness. The Pemigewasset Wilderness is located on the western part of the White Mountain Range and is the largest wilderness area in the state of New Hampshire. It includes the Franconia, Bond, Twin, Zealand, and Hancock mountain subranges and is home to some of the most difficult terrain in the area.

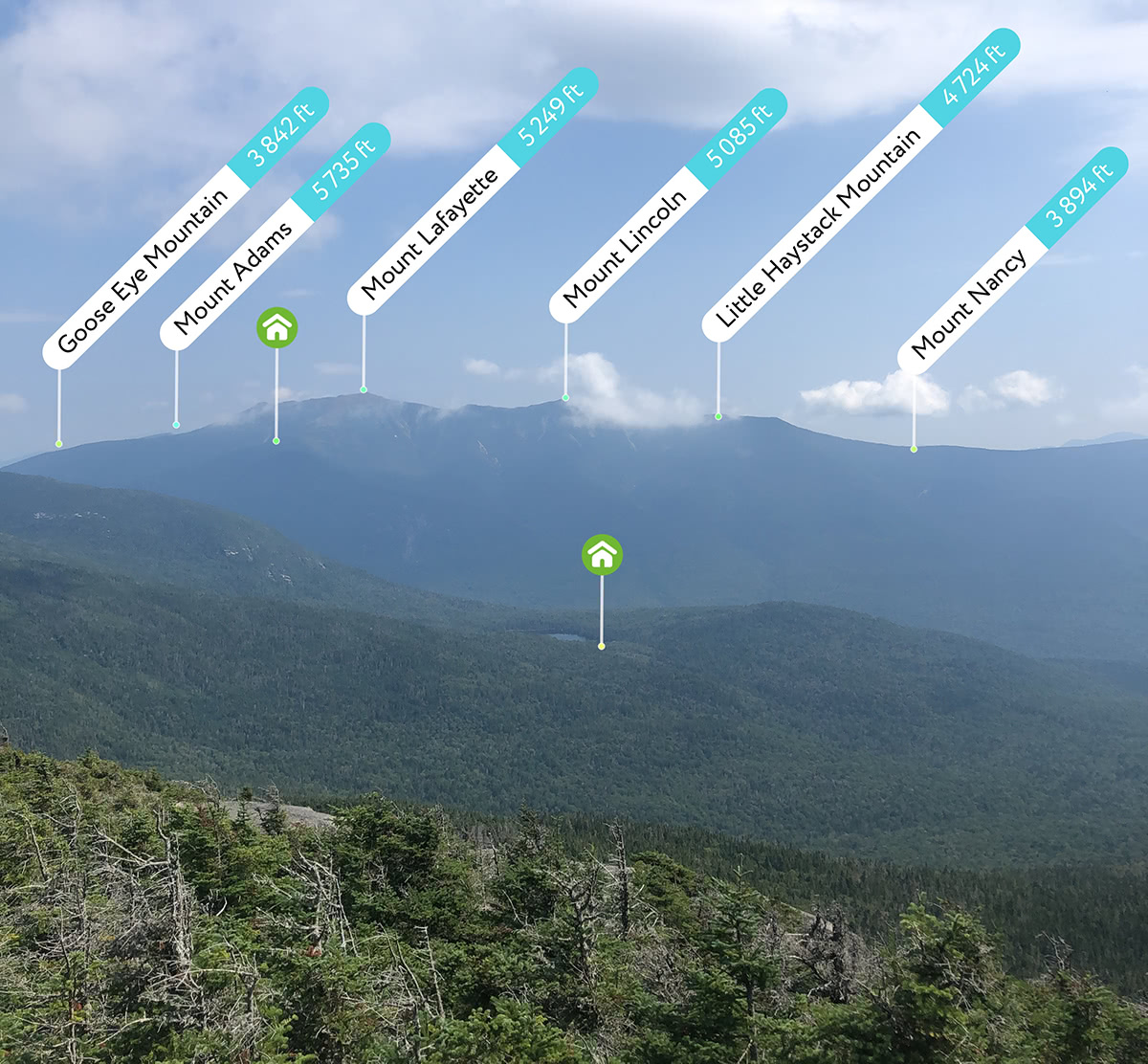

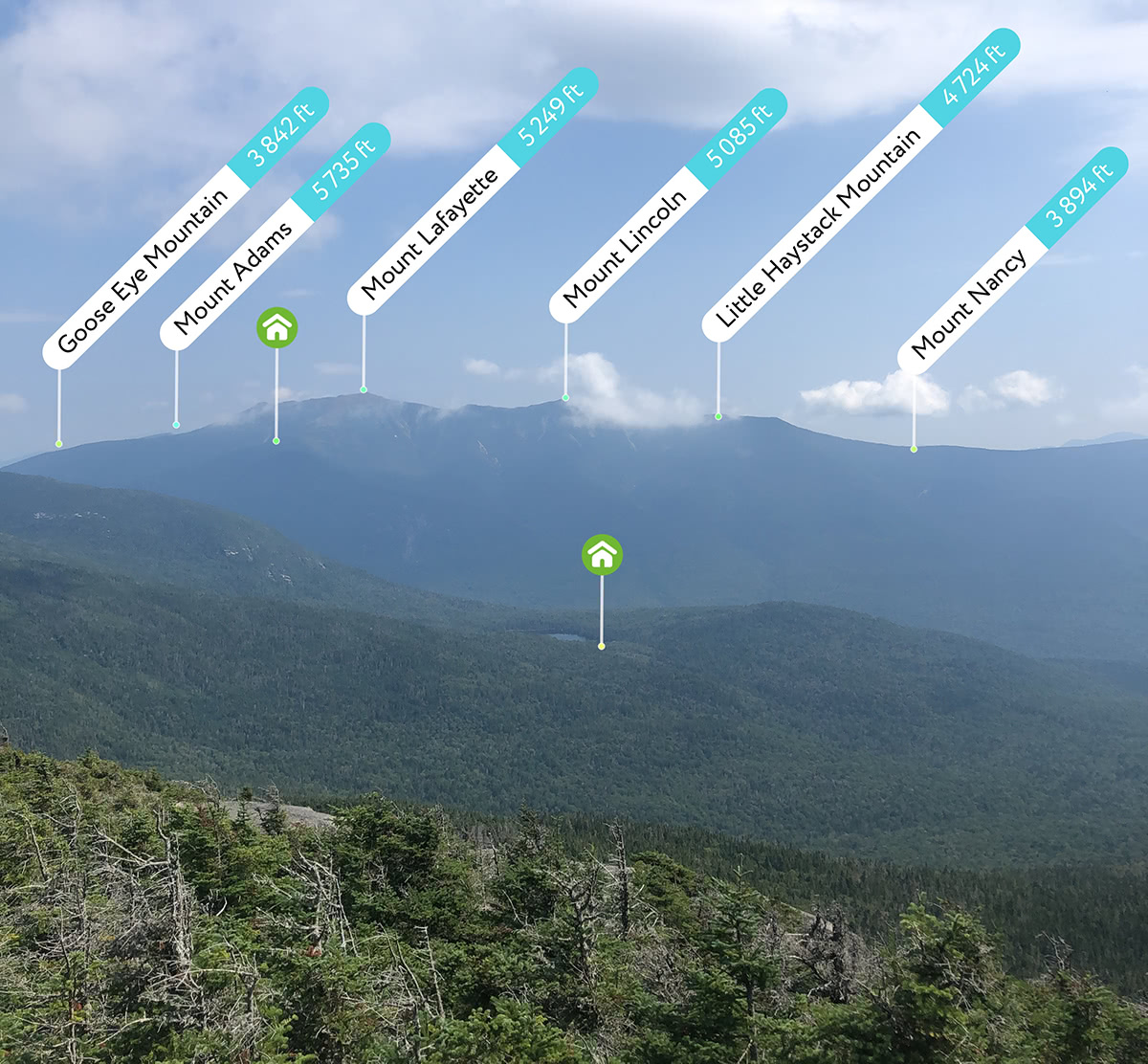

The range itself has a fairly unique geography, as it is characterized by the presence of two horseshoe-shaped ridges that are surrounded by low, wet river valleys. The western ridge is the more popular of the two and contains the Franconia, Twin, and Bond subranges. The most prominent peak on the range is Mount Lafayette 5,249 feet (1,600m), which can be approached by a variety of different trails.

Perhaps the most adventure-filled way to hike Mount Lafayette is to start at the Lincoln Woods Trailhead and set off on a trail affectionately known as the “Pemi Loop,” part of which is actually along the famous Appalachian Trail. After leaving the trailhead, hikers make their way up to a variety of smaller peaks, including Potash Knob 2,684 feet (818m) and Whaleback Mountain 2,586 feet (1,093m) as they ascend to the Franconia Ridge and the rocky summit of Mount Flume 4,328 feet (1,319m). From here, the ridge swells up and down, as it rises and drops below treeline.

Eventually, the trail makes its way to Mount Liberty 4,459 feet (1,359m) and Little Haystack Mountain 4,780 feet (1,457m) before it becomes more of a “knife-edge” trail, where expansive panoramic mountain views give way to significant drop-offs on either side. After ascending Mount Lincoln 5,089 feet (1,551m), the trail finally reaches Mount Lafayette 5,249 feet (1,600m).

At Mount Lafayette, hikers can choose to head back the Lincoln Woods Trailhead or continue down a shorter trail to the west. For a longer hike or backpack, hikers can continue on down the Garfield Ridge, where they’ll cross Mount Garfield 4,500 feet (1,372m) and Galehead Mountain 4,024 feet (1,227m). Weary hikers can exit the ridge from the flanks of Mount Galehead and head due south back to the Lincoln Woods Trailhead, while those who wish to carry on can make their way to the Twin Range.

Those of us still hiking will make our way down the Twin Range and climb up to the summit of South Twin Mountain 4,902 feet (1,491m) and then to the summit of Mount Guyot 4,580 feet (1,396m). Mount Bond 4,698 feet (1,432m) and Bondcliff 4,265 feet (1,300m) guard the southern part of the Twin Range and mark the start of the descent back down the the Lincoln Woods Trailhead where some well-deserved rest is warranted after a grand adventure.

On the top of a tall peak in the White Mountains, you might feel like you’re in the middle of a vast expanse of wilderness, but, it turns out that the hustle and bustle of city life aren’t too far away. Here are some of the main cities in the region and some of the best places to stay during your next White Mountain adventure:

Just a two and a half hour drive in good weather, the bustling metropolis of Boston is the perfect launching point for your White Mountain experience. Whether you’re from Boston or looking for a place to start your adventure, this major US city is filled with all of the culture, history, and fun that you’d expect in an urban jungle.

If you’re traveling from an international destination to get to the White Mountains, or just from another part of the United States, Boston’s airport is a great place to fly into to access the wilderness. There are some shuttle buses that bring people up from the airport to the mountains, but the easiest way to get around would be to rent a car and zoom north. Boston is a bit too far of a drive for a daily commute to the Whites, but it’s a great place to start or end your stay.

Although not nearly as big as Boston, Portland has many of the same cultural and historical benefits of a big city, without the crowds. Plus, Portland’s airport is frequented by many major airlines, so it’s another great place to fly into. At just an hour and a half away, Portland is a great place to escape to if the weather in the mountains chooses not to cooperate with your hiking plans.

North Conway, New Hampshire, and the surrounding towns are the perfect gateway to the eastern White Mountains. Just a 30-minute drive to the trails of Mount Washington and Pinkham Notch, North Conway is an outdoor enthusiasts’ holiday retreat. After a day in the hills, you can enjoy a hot shower at one of the area’s many hotels, a cold beer at a local ski-town bar, or some tax-free shopping at the outlet mall.

If you’re looking for more of that New England small-town feel, you can drive around the North Conway area and check out some of the famous (and adorable) covered bridges that connect the different towns. The bridge that forms the main entrance into the town of Jackson is particularly cute and worth a visit.

Lincoln, New Hampshire is the Western White Mountains’ answer to North Conway. If your travels and plans take you to the western edge of the range, Lincoln is a great place for a basecamp, whether that be at one of the town’s many lodges or campgrounds. Lincoln provides superb access to the Pemigewasset Wilderness, which is just 10 minutes by car from the town center. Franconia Notch State Park and all of its beautiful waterfalls are just a 15-minute drive, too, so there’s a lot to see around here if you’re not out hiking or skiing in the hills.

If you’re staying in Lincoln and want to get over to North Conway, you can even take a scenic drive along the Kancamagus Highway, which traverses the Whites from East to West. This highway takes you up and over some mountain passes and offers excellent viewing points for the whole range. Just be careful as you drive, though - moose and bear love to frequent the road!

Explore White Mountains (New Hampshire) with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.

ultra

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

fred-beckey-great-peaks

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

ultra

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

fred-beckey-great-peaks

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh

new-england-4000ers

nh-4000ers

northeast-115-4000ers

ymca-alpine-club-nh