Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

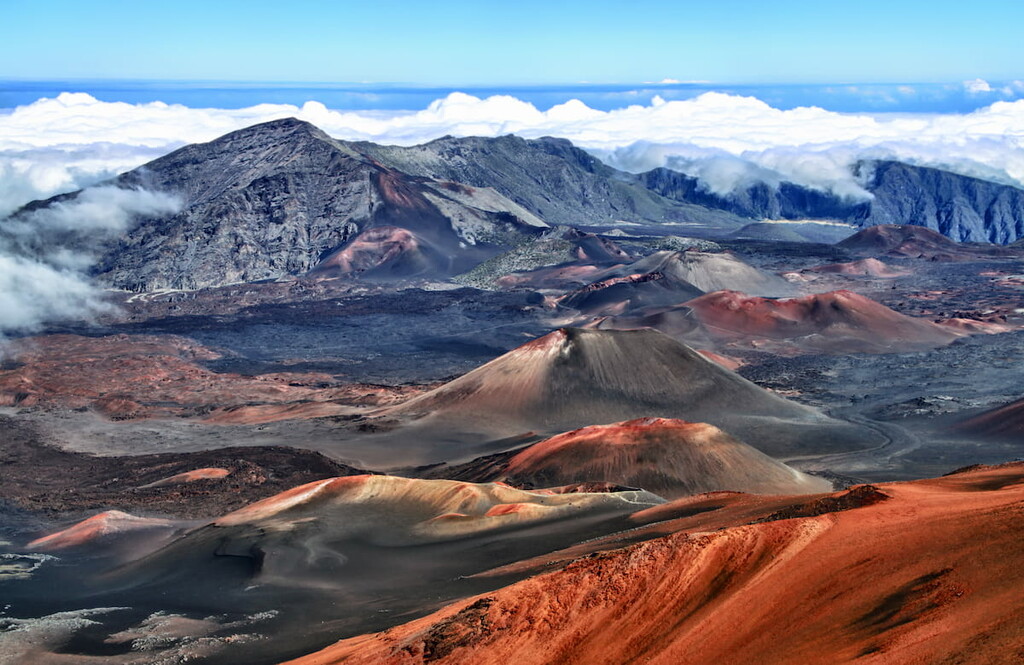

A sacred landscape of volcanoes, rugged coastline, alpine deserts, and ancient lava flows, Haleakalā National Park is a federally-protected area located in the eastern part of the island of Maui in the US state of Hawaii (Hawaiʻi). The park contains 37 named mountains, the highest and most prominent of which is Puʻu ʻUlaʻula on Haleakalā at 10,023 feet (3,055 m) in elevation.

Located on the eastern part of the island of Maui, Haleakalā National Park is one of two national parks in the state of Hawaii (Hawaiʻi). The park is located within Maui County and it contains some 33,265 acres (13,461 ha) of land, making it the 10th smallest national park in the US, making it just slightly larger than Cuyahoga Valley in Ohio and Black Canyon of the Gunnison in Colorado.

Haleakalā National Park was actually initially part of the former Hawaiʻi National Park, which also included Kīlauea and Mauna Loa in what is now Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park on the island of Hawaiʻi. However, the two parks were separated in 1961, and Haleakalā was expanded to its current size in 2005.

The park is situated around Haleakalā, which is a dormant volcano that dominates much of eastern Maui. While much of the park focuses on the mountain itself and its many volcanic features, it also includes parts of the island’s rugged eastern coastline (the Kīpahulu District), which is accessible only via the Hāna Highway.

Haleakalā National Park is home to a stunning array of geological features. The park itself is situated around a dormant volcano, Haleakalā.

Haleakalā is a shield volcano that’s believed to have erupted at least 10 times in the last millennia. It is believed that the volcano’s last major eruption took place about 400 to 600 million years ago, though evidence of its eruptive past is evident throughout the park. Since the volcano is simply dormant and not extinct, it could also erupt again in the future.

In fact, there are a number of lava flows within the park (including both pāhoehoe and ʻaʻā). However, it’s worth noting that the “crater” in the heart of the park is not a crater, but a valley that was created by thousands of years of erosion and landslides.

But, why exactly are there volcanoes in Hawaii, you might ask?

The general consensus among geologists is that the volcanoes of Hawaii (and the islands themselves) are the result of a hotspot that’s located under the Pacific plate. As the Pacific plate drifts northwest, it slowly moves over the hotspot.

This hotspot causes plumes of superheated rock to bubble up to the surface of the earth, creating massive shield volcanoes like Haleakalā in the process.

As the plate drifts northwest, however, it will eventually cause Haleakalā to lose its connection to the hotspot that feeds it. Over time, this will lead to Haleakalā’s extinction and the birth of newer volcanoes, such as those on the island of Hawaiʻi.

Major peaks in the park include Puʻu ʻUlaʻula, Hanakauhi, Kaumakani, Kuiki, and Pu‘uomāui.

Due to the sheer diversity of elevations and landscapes found within its borders, Haleakalā National Park is home to a superb array of flora and fauna. In fact, the park is home to no fewer than five different ecosystems, each of which supports its own collection of plants and animals.

At the highest elevations, the park is home to the alpine aeolian zone. This area boasts a harsh climate where only the heartiest of shrubs and grasses can survive. Some of the park’s highest slopes, especially near the summit of Haleakalā, are even home to tardigrades.

Tardigrades, which are often called water bears, are a phylum of micro-animals that thrives in some of the world’s most inhospitable environments. These animals can be found in the moss-covered lava plains of the park. In fact, the park is considered to be the home of the richest collection of tardigrade species on the planet.

Located right below the alpine zone, the park’s subalpine shrublands contain a mix of grasses and shrubs. Here, you can find a variety of species, such as pilo, ohelo, mamane, and pukiawe, all of which are fairly resilient and can withstand the variety climate at this high elevation.

Furthermore, visitors can find the nēnē, or the Hawaiian goose, in this region. The nēnē is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands and is found nowhere else in the world. It is currently listed as a vulnerable species and it is generally only found in shrublands, lava plains, and grasslands, such as those found in Haleakalā National Park.

On windward slopes in the park at the mid-elevations, rainforests dominate the landscape. These forests can receive anywhere from 120 to 400 inches (304 to 1,000 cm) of rainfall each year, so they’re capable of supporting a wide array of different flora and fauna.

Many of the species in these rainforests are native to the islands, including ʻōhiʻa and koa. If you’re lucky, you may also see the Hawaiian honeycreeper in these forests. The Hawaiian honeycreeper is a small bird that’s endemic to Hawaii and is known to live off the nectar of the region’s extremely productive flowers.

Meanwhile, on leeward slopes below the shrub zone, dry forests prevail. These forests receive less than 60 inches (150 cm) per year of rain and are becoming increasingly rare within the park. As a result of wildfire activity and introduced species, the dry forests in Haleakalā are highly fragmented, though you can still find small areas of the forest in the region.

Finally, Haleakalā is also home to a unique ecosystem around the ‘Oheʻo stream. The ‘Oheʻo stream runs throughout the park and is a great example of one of the very few natural riparian habitats in the state. In this unique ecosystem, visitors can find some rare native fish species as well as shrimp that live in the river itself.

Humans have lived in the area that is now Haleakalā National Park for more than one thousand years ever since the original settlement of the islands by people from Polynesia. In fact, the summit crater of Haleakalā is considered to be sacred to Native Hawaiians and it is known within the Native Hawaiian community as the “House of the Sun.”

European colonization of the region dates back to 1778 when Captain Cook first made contact with Native Hawaiians. By the 1820s, missionaries from the United States had arrived on the island of Maui.

The boom in the sugarcane trade later led to a massive increase in US interest in the region, which subsequently led to the importation of diseases onto the island.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Haleakalā Ranch was established by Henry Perrine Baldwin. This ranch also included part of the summit crater when it was first established. Haleakalā Ranch brought cattle grazing to the island, which became an important part of its economy after the end of sugar production in the region in the 1920s.

Nevertheless, the grazing of livestock and the introduction of other animals, such as cats, to the region, had massive impacts on the island’s ecosystems. In fact, the nēnē was extirpated from the island in the 1890s due to the introduction of predatory species (it has since been re-introduced).

In 1916, Hawaiʻi National Park (which included parts of Haleakalā) was established and in the 1930s, a road was built to the summit of Haleakalā. The construction of this road then led to the construction of the Haleakalā Visitor Center at the summit in the 1930s and the development of a number of observatories on the mountain.

It must be noted, however, that the construction of these facilities on Haleakalā has and continues to be a contentious issue for many Native Hawaiians. Indeed, many Native Hawaiians took part in peaceful protests in the 1960s to object to the construction of observatories on their sacred land, though these protests went unheard.

In 1961, Haleakalā was officially established as its own national park, independent from Hawaiʻi Volcanoes. Some two decades later, the park was also officially designated as an International Biosphere Reserve. Since that time, the park has seen a number of expansions to its territory, with the most recent expansion taking place in the early 2000s.

The park continues to be a contentious area, mostly due to the increasing number of observatories and developments taking place within its borders. These days, the park is also a popular tourist destination and outdoor recreation area, with over a million visitors traveling to Haleakalā each year.

Haleakalā National Park offers over 30 miles (48 km) of hiking trails for visitors to enjoy in the summit area and many more in other parts of the park.

It is worth noting, however, that the highest elevations in the park are over 10,000 feet (3048m), so caution is needed if you are not acclimatized to high elevations. Furthermore, the weather at the highest elevations of the park is fickle at best. The conditions can change rapidly, so be prepared for any eventuality while on the trail.

Finally, there are a number of regulations to be aware of when hiking in Haleakalā. The park has a strict 12 person group size limit, so only small group hiking is allowed. Camping in the wilderness areas of the park is also available by permit only, so be sure to check local backpacking regulations before your trip.

With that in mind, here are some of the most popular hikes in the park:

One of the most well-traveled paths in Haleakalā, Keonehe‘ehe‘e (Sliding Sands) is an 11-mile (17.8 km) long hike that starts at Keonehe‘ehe‘e Trailhead. It crosses the valley floor and passes by some of the most iconic places in the park.

Some of the many highlights of the trail include the crater floor, Pele’s Paint Pot, and Kawilinau, the latter of which is a large volcanic pit.

Since this is a point-to-point hike, some pre-planning is necessary before your trip. If you don’t have two vehicles in your group, the park actually recommends parking your car at Halemau'u and hitchhiking to the main trailhead at Keonehe‘ehe‘e. That way, you’ll hike toward your car, which helps simplify the logistics at the end of your hike.

Located in the coastal district, the Pīpīwai Trail is a 4 mile (6.4 km) round-trip hike through a freshwater stream and forest ecosystem.

This path offers a chance to see a bamboo forest and a number of excellent waterfalls. Some of the many falls on this trail include Makahiku Falls and Waimoku Falls, both of which are well worth visiting.

The steep and narrow Halemau'u Trail offers excellent access to the floor of Haleakalā crater. Over the course of 9.5 miles (15.3 km), the trail descends steeply into the crater, where you’ll get to see the ʻāhinahina (Haleakalā silversword), an endangered plant that only grows on the mountain.

This trail is also home to one of the park’s cabins, which can be reserved for camping if you’re lucky enough to get a permit. All in all, the Halemau'u is a stunning trek into one of the most beautiful and unique landscapes in the park.

Looking for a place to stay during your visit to Haleakalā National Park? Here are some of the best places to check out:

One of the largest communities on Maui, the city of Kahului is located in the western part of the island. It is home to about 26,000 residents and is the commercial center for the island.

Although Kahului is often considered to be more of an industrial and commercial area than a tourist destination, it does have one of the largest airports in Hawaii outside of Honolulu—Kahului Airport (Kahua Mokulele o Kahului). It also has great road connections to other parts of the island, as well as beautiful botanical gardens and some excellent museums.

Located in the south-central part of Maui, Kihei is a city of some 20,000 people that’s known for its sandy beaches. The city has about 6 miles (9.7 km) of beaches and a popular destination for tourists to the island.

Furthermore, the city is home to a number of important research stations and sanctuaries, including the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. Plus, Kihei is just 20 minutes by road from Kahului and 1 hour from the park, so it’s a great basecamp for your adventures.

Home to about 7,000 residents, the town of Makawao is located in the north-central part of Maui, just outside the Makawao Forest Reserve. Often called the hub of Maui’s “Upcountry,” Makawao is a center for commerce in the more rural and agricultural eastern part of the island. It is just 20 minutes by road from Kahului and 40 minutes from the park.

The small community of Hāna is one of the most isolated places on Maui. Situated in the eastern part of the island near the coastal part of Haleakalā National Park, Hāna is home to about 1,200 people as well as some stunning coastline.

Hāna is accessible only by the long and winding Hāna Highway, by air, or by boat. However, it is one of the most stunning places in the region and one of its best surfing destinations (Note: remember to respect local customs if surfing in the area).

Hāna is also home to some beautiful botanical gardens and the Waiʻanapanapa State Park, in addition to offering excellent access to the coastal regions of Haleakalā.

Explore Haleakalā National Park with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.