Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Victoria is Australia’s pint-sized powerhouse—well, by Australian proportions, that is—though that doesn’t negate the diversity and extent of relatively pristine natural spaces. In Australia, it’s known as the "Garden State;" it certainly has the upper hand over the Garden State of the U.S. (New Jersey). Amongst the state’s shadowy Eucalypt forests lies some of the Australian continent’s finest hiking, mountain biking, rock climbing, and skiing, to name just a few. Along the indented coastline, surfing and sea kayaking reign supreme. Alpine National Park is one of Australia’s premier mountain destinations, while the Twelve Apostles are one of the nation’s most popular oceanside attractions. In total, there are 2115 named mountains in Victoria. Mount Bogong (1986 / 6,516 ft) is the highest and most prominent mountain.

Victoria crams an abundance of geography into its 237,659 square kilometers (91,760 sq. miles). Bordered by the Bass Strait to the south—separating it from Tasmania—Victoria is tucked neatly between New South Wales to the north and South Australia to the west.

Despite its modest footprint, the state’s landscape is a sample platter of Australian geography. The rugged, indented coastline is seemingly endless, a stippled mix of cliffs and beaches. Victoria stretches out over 2,000 km (1,200 miles) of shoreline, much of which is accessible via the winding Great Ocean Road and its various offshoots. The coastline also includes Port Phillip Bay, Melbourne’s watery front yard, and the neighboring Western Port Bay, with “little” penguins (their actual name and defining characteristic, as the world’s smallest penguin species) and dolphins.

Volcanic plains stretch along the state's western reaches, while the Murray River has shaped a fertile plain along the northern border with New South Wales. Victoria’s plains open up into some of the state’s most productive agricultural zones. The Goulburn Valley and the Western District Volcanic Plains are fertile hotspots where dairy cows outnumber people, and recently extinct volcanoes peek out from the patchwork of farms.

Meanwhile, the Great Dividing Range forms the backbone of eastern Victoria, topped off by the Victorian Alps, where Mount Bogong reigns as king. Here, the landscape shifts from wet temperate forests to alpine meadows and even a handful of ski resorts, like Falls Creek and Mt. Buller. Alpine regions are defined by a unique Eucalypt species—the Snow Gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora)—which thrives above 700 meters (2,300 ft).

Significant rivers include the Yarra, winding through Melbourne, and the mighty Murray along the northern border. Patches of temperate rainforest remain, though not to the same extent as nearby Tasmania.

Melbourne is Australia’s second-largest city at 5.3 million residents and is the (self-proclaimed) cultural capital, with trendy cafes and street art ubiquitous. However, contrary to Victoria’s plentiful green space, Melbourne is also the nation’s densest and most urban metropolis.

Running down the eastern side of the state, the Great Dividing Range is Victoria’s backbone, formed over 300 million years ago during a tectonic party—a party of seismic proportions—that smashed ancient continents together. These mountains are carved from ancient sandstone and shale that were once at the bottom of an ocean before being thrust skyward.

Move west, and you’ll find yourself in one of the world’s largest volcanic plains, stretching across southwestern Victoria. The Western District Volcanic Plains were created by a series of volcanic eruptions that started about 5 million years ago and continued until around 5,000 years ago—basically yesterday in geological terms. A smattering of over 400 volcanoes ranges from conical hills like Mount Elephant to eerie crater lakes such as Lake Bullen Merri.

Head south, and land meets the sea in a dramatic clash of forces. The Great Ocean Road, one of Australia’s most famous drives, winds past limestone formations like the Twelve Apostles—although, spoiler alert, there aren’t twelve anymore, thanks to relentless erosion. These cliffs are made of limestone deposited during the Miocene epoch (20 million years ago) when the area was a warm, shallow sea. Over millions of years, waves and wind have sculpted these rocks into arches, caves, and stacks.

With so much limestone, it’s only natural that Victoria would develop a subterranean network of caves, a phenomenon known as karst. Limestone is soft and porous, and acidic water dissolves the rock over millions of years. Victoria’s karst landscapes include the area around Buchan, where limestone and dolomite have been sculpted into caves filled with stalactites, stalagmites, and underground rivers.

Is money the root of all evil, or is evil the root of all money? During the mid-19th century, gold-bearing quartz reefs in Victoria precipitated a gold rush, particularly in places like Ballarat and Bendigo. The boom brought many early settlers and ushered in the state’s resource-extraction-based economy.

Like the rest of Australia, Victoria's ecology is quirky and diverse. Ecosystems range from alpine tundra to misty rainforest to sun-soaked beaches. Average rainfall reaches two meters (80 inches) in some of the mountainous regions in the northeast, where remains of temperate subtropical forests can be found in the lowlands. Meanwhile, the inland northwest has bonafide desert, with annual rainfall as low as 20-30 cm (8-12 inches).

Victoria’s High Country features gnarled snow gums that twist and turn into surreal, ghostly shapes. These hardy eucalypts are among the few trees that can survive the snowy winters. In the warmer months, these alpine meadows explode into a riot of wildflowers and rare species like the critically endangered mountain pygmy-possum (less than 2,000 remaining in the wild), which hibernates under the snow.

Head towards the Dandenong Ranges or the Otways, and you’ll find yourself in misty, fern-filled forests where giant tree ferns and towering Mountain Ash trees—some of the tallest flowering plants in the world—create a preternatural and prehistoric canopy. These moss-covered temperate rainforests are brimming with birdlife, like the noble lyrebirds that mimic everything from chainsaws to camera shutters.

Despite covering just .14% (32,000 hectares) of Victoria’s land area, temperate rainforests harbor 30% of the state’s rare and endangered species. The remaining forests occupy mainly sheltered, south-facing gullies that retain moisture and ward off bushfires.

Victoria’s 2,000 kilometers of coastline are teeming with life. Rocky reefs, seagrass beds, and kelp forests beneath the waves host everything from the flamboyant seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) to playful seals and migrating whales.

Victoria’s native grasslands and woodlands might not be as glamorous as the dazzling forests or alpine vistas, but they’re ecological powerhouses in their own right. Grassy plains are home to many species, including kangaroos, echidnas, and the critically endangered Plains-wanderer. These ecosystems are under constant threat from agriculture and urban development.

Victoria’s landscapes have evolved with fire as a natural part of the ecosystem. From the savannas of the west to the dense mountain forests, many of the state’s plants have adapted to rely on fire to regenerate. Eucalypts, for example, release seeds after a fire, and many native plants only flower after a good scorch.

There’s a difference between beneficial burns and devastating wildfires. In recent years, warmer temperatures and drier soil conditions have produced vicious blazes known as crown fires. Rather than clear out the understory, these fires reach above the forest's canopy, killing Eucalypt trees and wildlife and making it difficult for the forest to regenerate. Koala bears, for example, instinctively head for the top of the Eucalypt during a fire and cannot escape if the flames burn higher. It’s one of the reasons their population has decreased to 100 - 500 thousand from an estimated 10 million pre-colonization (95-99% decimated).

Victoria’s human history is a tale stretching through 65,000 years of Aboriginal heritage, followed by the resource extraction and colonial ambition of Western newcomers. Australia is still reconciling its role as the perpetrator of one of the most devastating colonization episodes in history, similar to North America. In the modern-day, PeakVisor readers can be thankful that Victoria has matured into a playscape for mountain and nature enthusiasts, as well as a cultural capital.

Long before Europeans showed up with their thirst for riches, Victoria was home to a rich tapestry of Aboriginal cultures, including the Wurundjeri, Bunurong, and Taungurung peoples, among many others.

The Aboriginal people arrived in Australia approximately 65,000 years ago; their closest lineage is ancient Asian peoples. Subsequently, their gene pool diverges.

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal communities lived in relative harmony with the land, managing its resources through sophisticated practices like controlled burning—the original bushfire management. Like the existence of other indigenous societies, theirs was subsistence-oriented. Resources were relatively abundant, and people worked only a few hours a day, leaving plenty of time for the development of languages (over 500 distinct forms), spirituality, and complex community and familial hierarchies, structures, and laws.

The year 1788 marked the first passage of James Cook and the beginning of the colonization of the Australian continent. Compared to the Americas, colonization was relatively rapid; by the early 19th century, it was reported that an Australian dialect had already evolved from standard British English.

The single most important event in the modern history of Victoria is the Gold Rush of 1851. For a number of years, Victoria was a top producer of gold on a global scale. Between 1851 and 1896, the state yielded a total of 1,898 metric tons of this coveted yellow element. Therefore, Victorian gold from this period comprises around 1% of the total above-ground supply.

As you can imagine, the discovery of such monumental amounts of gold launched Victoria into the global economic arena. The city of Melbourne exploded in size and wealth, eventually earning the nickname “Marvellous Melbourne.” It even became Australia’s capital city for a time, until the city of Canberra was built and the ACT (Australian Capital Territory) was created.

Australia was spared the destruction of Europe and Asia in the aftermath of WWII. The nation had already set an early precedent for national parks; the Royal National Park in New South Wales (1879) was only the world’s second. Mount Buffalo National Park was Victoria’s first in 1898.

After 1956, the rate of conservation increased exponentially, going from ~250,000 to nearly 3 million hectares of national parklands in the present day. Mountain sports began growing more popular as well. Even though Mont Blanc had seen an ascent two years before the first Europeans even stepped foot on the continent, mountain climbing hadn’t yet caught on in Australia. Sure, there were some alpine-style ascents here and there, especially in the Grampians, but not much in the way of technical climbing.

Arapiles, widely considered Australia’s finest rock climbing venue, saw its first ascent in the early ‘60s and now features a couple of thousand routes on quartzite. The nearby Grampians feature over 6,000 routes on sandstone in a beautiful national park setting.

Surfing and mountain biking have also developed in Victoria. Australia has produced international champions in both sports. Much of the best MTB riding in Australia is in Victoria, particularly around the Bright area.

Victoria is Australia’s second most populated after NSW, the second fastest-growing population after Western Australia, and the second highest GDP after NSW.

It comprises just 3% of Australia’s land area but 25% of the nation’s population and GDP.

Victoria is one of the world’s premier hiking destinations, particularly around the coast, the Victorian Alps, and the Grampians.

Australia is relatively close to the equator (mid-30s latitude), and sun exposure is very real. Sunscreen is a must. Most stores don’t even sell anything below 50 SPF.

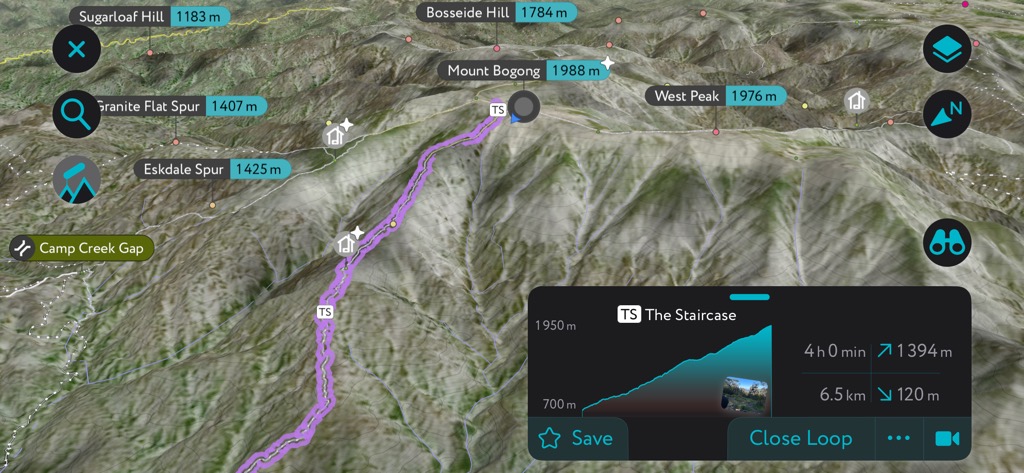

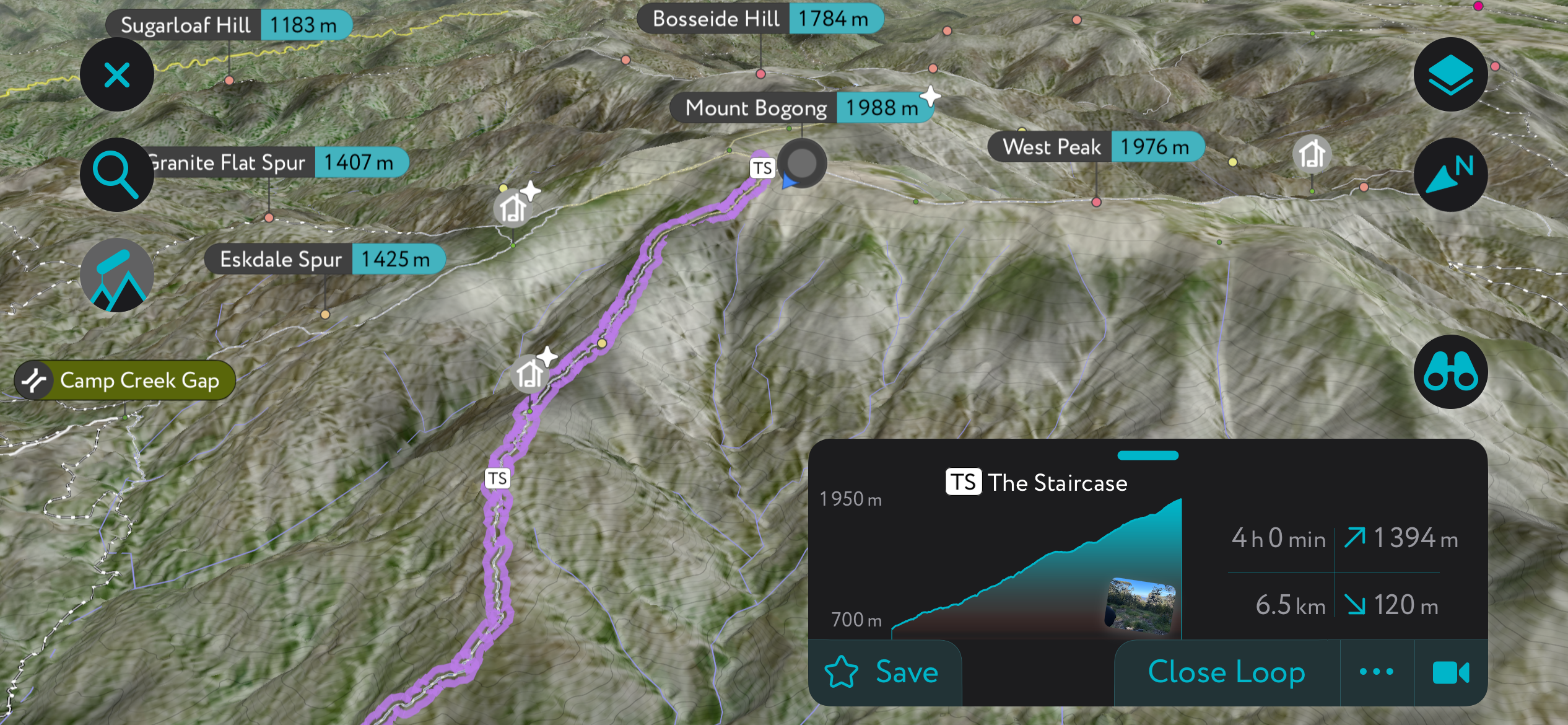

Victoria’s tallest peak reaches 1,986 m (6,516 ft). The Staircase hiking route starts near Mount Beauty, at the Mountain Creek camping and picnic area. Park here.

Next, you’ve got a devilish ascent of over 1,400 meters (4,600 ft), one of the biggest vertical gains you can find in Australia. It’s going to take the better part of the day, and you’ll be exposed to the notorious Victoria weather for hours on the upper plateau.

The summit features views of the upper portion of Alpine National Park, around a wilderness called the Bogong Remote and Natural Area.

Mt. Feathertop (1,922 m / 6,305 ft) is Victoria’s second-highest peak and is located centrally in Alpine National Park. It’s got a famous ridge called the Razorback that features one of Australia’s best alpine hikes.

The 22.7 km (14.1 miles) out-and-back starts at the Diamantina Hut near Harrietville. You can park here. Prepare for about 900 m (3000 ft) of vertical gain to the summit. The ridge is exposed, so it's important to have good weather and wear plenty of sunscreen!

This 160-kilometer (100-mile) trail traverses much of the Grampians National Park, including the summit of Mount Difficult. It’s one of Victoria’s great through-hikes, taking hikers from the north to the south end of the park.

Expect to take 1-2 weeks to finish this route, though the nature of the hiking is such that you won’t be doing 40 km days. An abundance of wild camping sites are spread along the route. Be mindful of fire bans during the summer.

We’ve covered some of the best alpine hikes, and now for something completely different: the Surf Coast Walk.

The 44-km (30-mile) route generally starts at the northern end at Torquay and heads south into Great Otway National Park. There are plenty of wild beaches and coastal bluffs to explore throughout 12 distinct sections, each of which can be broken into a day hike. In fact, much of the trail is shared with cyclists.

For the sections along the beach, be mindful of the tides.

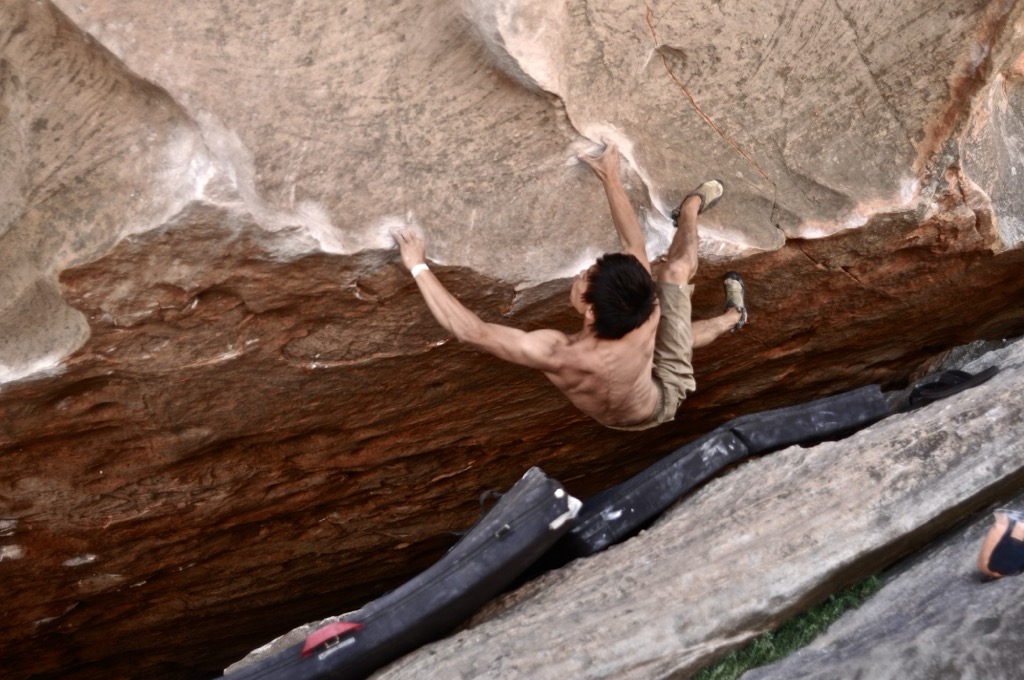

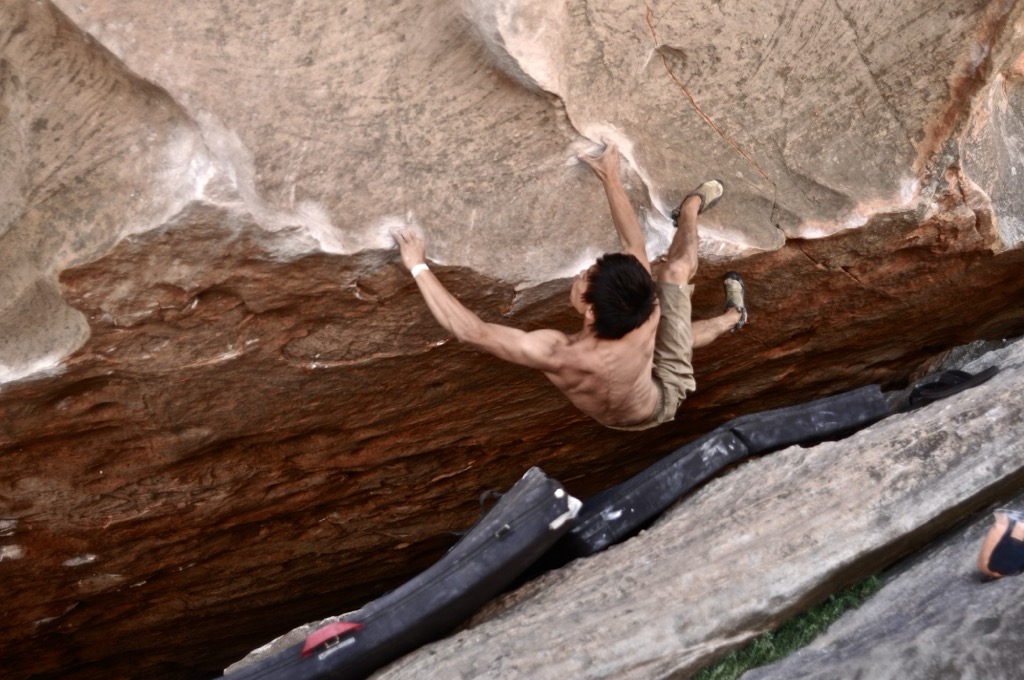

Araps, as it’s known to Australia’s seasoned rocksmiths, is the nation’s most highly regarded climbing destination both domestically and internationally.

What’s so good about Araps? Well, let’s start with the camping. There’s only one place to camp, but it’s right near the base of the cliff—read short approaches—and it’s super cheap, around 3 AUD per person per night.

Next, you’ve got the climbing. Most of the climbing here is traditional—placing your own protection—with routes across every grade. Out of the casual couple thousand routes, the majority are single-pitch, although you also have hundreds of multi-pitch outings up to 150 m (500 ft). The rock is superb quartzite, a durable, hard sandstone with embedded crystals offering good friction. The sandstone is hard enough that protection is typically excellent. Bring tape or crack gloves!

With an abundance of routes, camping, and short approaches, it’s easy to pack in a lot of pitches in a day.

Best of all, Arapiles is just a few hours from Melbourne, where about 80% of Victoria’s population resides. That makes getting out here very easy.

The Grampians are relatively close to Arapiles and the commute from Melbourne is similar. However, the climbing is quite different. The place is vast, with over 6,000 routes ranging from short, difficult sport routes to long, adventure-style trad climbing. As if that weren’t enough, it’s also Australia’s premier bouldering destination.

Unlike Arapiles, the Grampians' climbing is spread out. Some crags are roadside while others are quite remote. You might want to purchase one of the several published guidebooks before heading out here.

Mount Buffalo is some of the highest rock climbing on the continent. Therefore, it’s likely the best place to go in the dead of summer when the rest of Australia is blazing hot (unless the weather is good down in Tasmania).

Mount Buffalo is where you’ll want to head if you love granite climbing. It’s not Yosemite, but you’ll enjoy some great trad placements and alpine-style climbing in the Gorge. As you would expect from granite, there are also friction-y, bolted slabs at the top of the plateau.

There’s some paid camping around the park, and it’s not far from the town of Bright, where you’ll find plenty of other stuff to do if you’re taking a rest day. Mount Buffalo is 3.5 hours northeast of Melbourne.

The town of Bright is one of the meccas of Australian MTB. There are two main areas: Mystic Mountain right in town, and Mt. Beauty further down the road. Six of the “Dirty Dozen” trails, a selection of Victoria’s best alpine riding, are around Bright (Mystic Mountain, Big Hill, and Falls Creek areas).

Mystic Mountain is run by the same folks (Dirt Art) as the more-famous Maydena, in Tasmania. It’s a paid-shuttle gravity operation with an emphasis on stellar hand-built trails. Shuttles are around 100 AUD per day, while the pedal-only option is 15.

Meanwhile, Big Hill Mountain Bike Park in Mount Beauty is a half-hour drive up the road. You can self-shuttle these trails or pedal up the fire road. Another 30 minutes farther, Falls Creek Bike Park offers lift-serviced flow trails but is only open in the summer (Nov-April).

Domestic and international visitors alike will likely pass through Melbourne to access the rest of Victoria. Melbourne is what we would describe as a culture capital: world-class street art, a cultish coffee scene, plenty of eclectic fashion, etc.

For those into spectator sports, Melbourne is obsessive about the AFL, or the Australian Football League. It’s not the football you’re thinking of; this is sort of like a mix between European football (soccer) and rugby. The city hosts the Australian Open tennis tournament, as well as an annual F1 event at Albert Park.

The iconic and charming trams rattle along the city streets, connecting the dots of Melbourne’s many neighborhoods. The city is also a foodie’s paradise, with a dizzying array of cuisines. You definitely won’t find restaurants this good anywhere else in Victoria, or Australia for that matter.

The city has been in a good-natured feud with Sydney over who is the top dog since pretty much the inception of Australia. The proud residents of both cities will defend their turf to no end, but, alas, they are very different.

Perhaps none of this appeals to you; in that case, Melbourne is only a few hours from most places in Victoria, so you can just launch off on your adventure.

Bright, Victoria, is a postcard-perfect town of about 2,500 people nestled in the Ovens Valley and surrounded by the Victorian Alps.

Bright is where each season brings its own kind of magic. In autumn, the town transforms into a kaleidoscope of red, orange, and gold. Winter rolls in with snow-capped peaks, turning Bright into a basecamp for skiers at Mount Hotham and Falls Creek. In spring and summer, the whole town throws on a pair of hiking boots or hops on a mountain bike to explore the 50 km of singletrack at Mystic Mountain. Rocksmiths will relish in rock climbing galore at the aforementioned Mount Buffalo National Park. If those activities aren’t good enough for you, there’s also paragliding. Australia is a massive country (with lots of driving), and it’s a rare treat to have so much in such close proximity.

On the other hand, you don’t need to do any sports to spend a day or three here. The whole region is quite bucolic, a patchwork of farms and vineyards—yes, for a splash of sophistication, Bright is home to several wineries. Just cruising around sampling the local fare is enough for many people.

The climate is a rarity in Australia. In summer, it can get hot but not too hot, and it really cools off at night. Conversely, the winters are actually relatively mild, with snowfall confined to the surrounding peaks. You’ve also got plenty of rain, especially in winter, an increasingly rare commodity in Australia.

Most of Australia was built after 1950, so the whole country has a bit of a new vibe. But Ballarat is a true blast from the past. The central district retains its mining-era charm through and through; it could be straight out of a Clint Eastwood movie, even though it’s on the complete other side of the world.

The grand Victorian—the time period, that is—architecture is the direct result of the metric tons of gold extracted from the ground here. Overnight, Ballarat became one of the planet’s wealthiest cities. You can learn more about the boom at the Sovereign Hill Museum. There’s also the Botanical Gardens, complete with serene ponds and wandering peacocks.

With a population of 119,000, Ballarat happens to be the third-largest inland city in all of Australia, a testament to the concentration of people along the coasts. It’s just an hour outside Melbourne on the way to the Grampians National Park and Arapiles.

Explore Victoria Mountains with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.