Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

If Australia is the “land down under,” then South Australia (SA) is like the “land down under the land down under.” Even Australians don’t venture here, let alone the rest of the world. But that’s their loss; SA is a land beyond time. It’s like California and New Mexico conceived a child in a parallel universe, with vineyards and lush forests giving way to the desolate, parched mountains and badlands of the interior outback. SA is bigger than most countries. It’s not mountainous per se, but it’s not flat either. In total, there are 2915 named mountains in South Australia; Mount Woodroffe (Ngarutjaranya) (1,437 m / 4,715 ft) is the highest, while Saint Mary Peak (1,171 m / 3,842 ft) is the most prominent. Let’s take a deep dive into this vast frontier and its forgotten ranges.

Here at PeakVisor, we specialize in mountains. South Australia may not be home to legendary mountain objectives, but it is certainly no stranger to wilderness and solitude, with just 1.7 million people calling this vast territory home. Moreover, over 75% of those people live in the metropolitan area of Adelaide, the state’s capital and largest city, with a population of 1.4 million.

South Australia’s mountains range from the dramatic escarpments of the Flinders Ranges to the more modest—despite the name—Mount Lofty Ranges, just outside Adelaide.

Flinders Ranges: The most extensive range in SA stretches 430 kilometers (270 miles) from Port Pirie into the arid Outback, featuring summits like Saint Mary Peak and the Wilpena Pound amphitheater.

Mount Lofty Ranges: A prominent range near Adelaide featuring Mount Lofty Summit and the scenic Adelaide Hills. These peaks are the wettest part of South Australia, with some weather stations averaging over 1000 mm (40 inches) of rain annually. Meanwhile, South Australia is the driest state in Australia, which is already a notoriously dry country.

Gawler Ranges: Located on the Eyre Peninsula along the central coast of SA, the Gawler Ranges are known for their volcanic rock formations and landscapes shaped by ancient lava flows.

Musgrave Ranges: These rugged and remote hills occupy the far northwest of South Australia, close to the Northern Territory border. Ngarutjaranya (Woodroffe), the state’s highest peak, is in the Musgrave Ranges.

Gammon Ranges: Part of the northern Flinders, these ranges are more rugged and isolated, with unique desert flora and fauna.

Hanson Ranges: A smaller range in SA’s northeast that extends into the Northern Territory.

Australia has an excellent infrastructure of federally funded parks and conservation areas. According to the South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Service, there are no less than 146 national-level parks in the state. These are dispersed throughout SA, though they’re mostly along the coastline and in the mountains.

The Flinders Ranges and Kangaroo Island are the two most unique and popular destinations for out-of-state or international visitors, but SA is overflowing with incredible parks. Let’s take a look at a few of the most significant.

The Flinders Ranges are like the start of SA’s Outback frontier. Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park protects the heart of the range and features breathtaking mountains like Wilpena Pound. The area is home to thousands of kangaroos, wallabies, emus, and other creatures. There are trails for all levels, from short walks to challenging hikes like Saint Mary Peak, SA’s most prominent mountain.

The park’s terrain features ochre-colored sandstone cliffs and gorges, with accessible hikes to rock art sites and sweeping mountain views. Ikara is an area of cultural significance to the Adnyamathanha people.

Mount Remarkable National Park protects the Southern Flinders Ranges and the popular Alligator Gorge. In case you were wondering, many things can kill you in Australia’s bush, but alligators aren’t one of them. You won’t find any on the continent (the closest wild specimen would be in China). Nor will you see crocodiles here; they’re only in northern Australia.

Kangaroo Island is one of Australia’s most iconic locales, though it’s less known outside the country. It’s one of the best places to see koalas, the world’s cutest animal (subjective, sure, but difficult to argue against).

Kangaroo Island’s Flinders Chase National Park is known for its unique rock formations, such as the Remarkable Rocks and Admirals Arch. The park is a diverse wildlife sanctuary for koalas, echidnas, seals, and more. The bushfires of 2019-20 severely torched the forests here, killing most of the koalas, though recovery is underway, and the coastal scenery is still surreal.

Witjira National Park protects one of Australia’s most extreme landscapes. The park features unique desert flora and fauna and is popular for 4WD adventures and camping, as well as the Dalhousie Hot Springs.

Belair National Park is located just 25 minutes from downtown Adelaide and is South Australia’s oldest national park and a favorite for family outings. This nature escape features walking trails, historic sites, picnic areas, and native wildlife (including koalas). Overall, it has more of a curated city park vibe—there are 29 tennis courts—but it is still a great way to escape the urban expanse.

Coorong National Park stretches along SA’s southeast coast, showcasing a coastal wetland with lagoons, sand dunes, and salt pans; it’s known for its birdlife.

The Flinders and Mount Lofty Ranges stretch north to south from the middle of SA to Adelaide and are geologically related. It’s a familiar tale; these ranges began as ancient seas where sediments accumulated on the seafloor about 500 million years ago. Sediments were then uplifted during tectonic mountain-building episodes. Since the uplift, erosion has steadily worn away at the sandstone, forming the mid-sized peaks we see today. The Flinders Ranges are also well-known for their Ediacaran fossils, some of the earliest records of multicellular life.

The Gawler Craton covers much of the state’s central and southern regions and is one of Australia’s oldest geological foundations. The craton is rich in copper, gold, and uranium. The biggest mining sites exist around Olympic Dam and Roxby Downs. Some of Earth’s oldest rocks exist here, dating back over 3 billion years. These are mainly granitic and gneissic rocks, formed over intense heat and pressure, that have gradually been uplifted toward the surface.

SA’s southern coast is dominated by the limestone-rich Nullarbor Plain, a vast, flat expanse stretching hundreds of kilometers. The Nullarbor comprises the remains of ancient marine organisms from around 25 million years ago when the area was submerged under a shallow sea.

The youngest mountains in SA are the volcanic formations in the state's southeast, particularly around Mount Gambier and Mount Schank. Mount Gambier features four craters, including the well-known Blue Lake (Warwar). The most recent eruptions occurred approximately 5,000 to 6,000 years ago.

South Australia's ecology is as diverse as its landscapes, with arid deserts, temperate woodlands, coastal ecosystems, and unique island habitats. It’s not the most biodiverse state in Australia (Queensland), but SA—especially Kangaroo Island—is a great place to view wildlife.

Extreme temperatures and limited rainfall define the Simpson Desert, the Musgrave Ranges, and the rest of the arid north. The record high temperature is 50.7℃ (123.3℉) at Oodnadatta, which is also the highest temperature recorded in Australia. This area is known as the Outback, a term that includes almost everywhere in the Australian interior.

The far north Outback of SA is one of the planet’s most extreme environments. Vegetation is sparse but highly adapted, with species like spinifex grasses, saltbush, and acacia scrub. Fauna includes reptiles like the thorny devil, red kangaroos, wedge-tailed eagles, and emus.

Many species are nocturnal or crepuscular, conserving energy during the hot days and becoming active in the cooler nights, mornings, or evenings. Despite the proximity to the equator, the dry air and cloudless skies allow nights to cool off quite significantly.

Like the Musgrave Ranges, the Flinders Ranges are defined mainly by desert ecology. The craggy sandstone mountains are host to specialized plant species, such as native cypress pines and salt-tolerant shrubs. However, unlike the desert, you will find stands of Eucalypt where conditions allow, mostly at high altitudes and protected gullies. The Flinders Ranges are home to reptiles, including several skink species and the bearded dragon, while bird species include the endangered short-tailed grasswren.

Kangaroos and wallabies are ubiquitous throughout Australia, but the Flinders Ranges is notable for the yellow-footed rock wallaby, an agile marsupial adapted to steep, rocky outcrops. It’s one of nineteen species of rock wallabies, though it’s now classified as “near threatened” by the IUCN, mainly because it’s been extirpated from most of its former range.

The flora and fauna of the Flinders Ranges are highly adapted to seasonal water scarcity, relying on the few ephemeral water sources and sheltered gullies that retain moisture longer.

Moving southward, the Mount Lofty Ranges and the temperate woodlands of the Adelaide Hills present a cooler, more temperate climate, supporting dense eucalypt forests and a variety of understory plants. These forests are home to koalas and bird species like rainbow lorikeets and sulphur-crested cockatoos.

South Australia’s coastlines and marine environments add another layer of ecological diversity in the form of wetlands and Mediterranean forests.

The Coorong and Murray Mouth region, where the Murray River meets the Southern Ocean, is a significant wetland home to pelicans and migratory shorebirds from as far as Siberia. Salt-tolerant plants such as mangroves dominate these coastal wetlands.

The rugged Eyre Peninsula, known for its clear waters, is home to the Great Australian Bight’s marine life, including southern right whales, Australian sea lions, and great white sharks. The coastal heathlands and cliffside habitats support species adapted to sandy soils and saline conditions.

The isolated nature of Kangaroo Island has led to the evolution of endemic flora and fauna. Most famously, the island’s eucalypt forests support Australia’s densest koala populations. Ironically, the koalas were introduced and have since flourished; their population doubled every five years from the late nineties to the 19-20 bushfires, which then decimated about 80%. They’re difficult to spot as they generally rest and feed high up in the towering Eucalypt canopy. They spend most of their day (~20 hours) sleeping and only feed for a few hours, most often in the evening. The island has a few sanctuaries where you can see them more easily.

South Australia’s human history is a tale stretching through 65,000 years of Aboriginal heritage, followed by the resource extraction and colonial ambition of Western newcomers. Australia is still reconciling its role as the perpetrator of one of the most devastating colonization episodes in history, similar to North America.

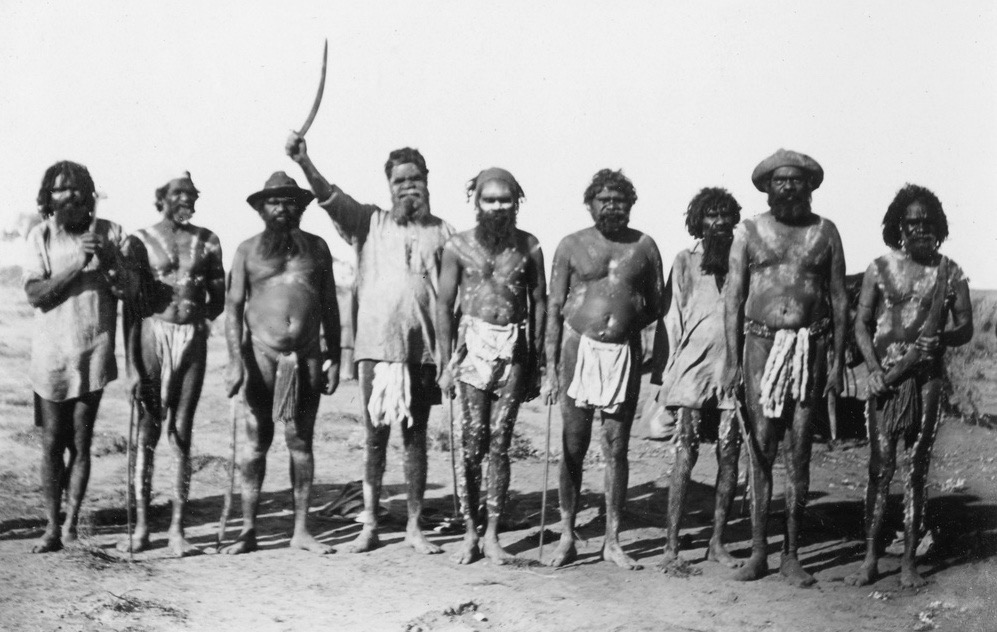

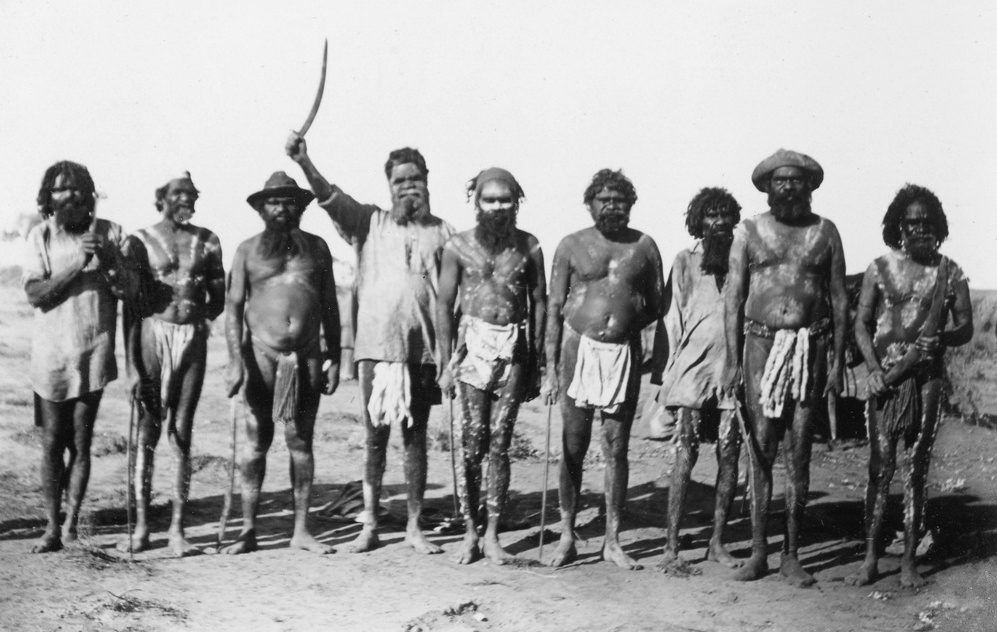

Long before Europeans showed up with their thirst for riches, SA was home to a rich tapestry of Aboriginal cultures, including the Kaurna, Ngarrindjeri, Adnyamathanha, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara, and Narungga.

Aboriginal people arrived in Australia approximately 65,000 years ago; their closest lineage is ancient Asian peoples. Subsequently, their gene pool diverges. It’s unclear exactly when they arrived in SA, though archaeologists conservatively estimate it at 45,000 years ago.

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal communities lived in relative harmony with the land, managing its resources through sophisticated practices like controlled burning—the original bushfire management.

Like the existence of other indigenous societies, theirs was subsistence-oriented. In much of their homelands, resources were relatively abundant, and people often worked only a few hours a day. This left plenty of time for the development of languages (over 500 distinct forms), spirituality, and complex community and familial hierarchies, structures, and laws.

One of the developments of Aboriginal societies was the oral tradition of Dreamtime stories, which are foundational narratives for the origins of people, animals, the land, and the Earth, among other things. The stories served as more than just religious myths; they had relevance in law and governance, as well as spirituality. Dreamtime stories vary across cultures and language groups; some of this diversity has been lost in tandem with the diminishing connection of language.

Apart from the coast, SA is a much harsher environment than many Aboriginal homelands in other parts of the continent. Aboriginals were well adapted to survive in the desert, though they subsisted in lower numbers than the coastal regions.

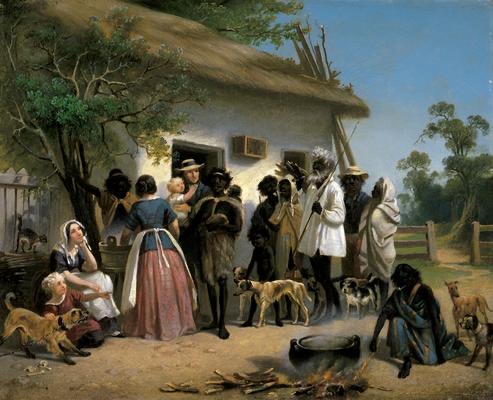

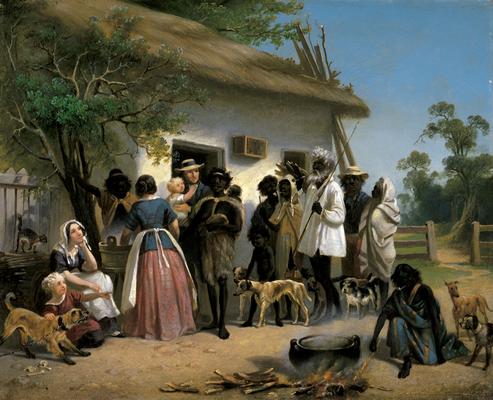

The year 1788 marked the first passage of James Cook (he landed around the Sydney Harbor) and the beginning of the colonization of the Australian continent. Compared to the Americas, colonization was relatively rapid; by the early 19th century, it was reported that an Australian dialect had already evolved from standard British English.

Colonization in SA happened a few decades later. Unlike other Australian colonies, SA was established as a free colony in 1836, meaning it was never a penal colony for British convicts, like other Australian states. Instead, it was founded on principles of systematic colonization, envisioning a structured society that balanced labor, capital, and land ownership. The system proposed the sale of land to finance immigration, attracting skilled laborers who would work for early landowners and eventually settle on their own land.

Adelaide was selected as the capital, and the city's layout was planned by surveyor Colonel William Light, who designed it with wide streets, open squares, and green spaces—in contrast to British cities' crowded, narrow, and generally disgusting streets.

By the late 19th century, South Australia’s economy was proliferating rapidly, fueled by agriculture and mining. SA became the first Australian colony to grant women the right to vote and to stand for parliament in 1894. However, despite some progressive influence in the state’s founding and early governance, the expansion of agriculture and settlement ultimately led to the displacement of Indigenous communities. Over time, Aboriginal people faced severe restrictions on their movement and were pushed to the fringes of society, where they remained.

As a whole, South Australia is one of the most rural states of any developed country. The vast majority of the modest population lives in Adelaide; the next biggest town is Mt. Gambier, at just under 30,000 people. As such, it’s got a reputation as a pretty sleepy place. Nature is the number one attraction here, whether it’s the mountains, the coast, the desert, or the wildlife.

At PeakVisor, we love remote places where we can spread our wings and fly off into the mountains. SA offers plenty in that regard, having successfully preserved some of its natural capital through national parks and the like. In the next section, let’s check out some of the state’s finest hiking destinations.

SA is a vast state with hundreds of parks and very few people. There are thousands of hiking trails, including Australia’s longest marked trail, the Heysen Route (1200 km). Here are a few of the most famous hikes to keep on your radar.

At PeakVisor, we love information. That’s why we write articles like this one.

For even more information on thousands of additional hikes across SA, check out the PeakVisor App. In fact, we’ve compiled information on all publicly maintained walking tracks across the country, formatted onto our 3D maps.

You can track your hikes directly on the app, upload pictures for other users, and keep a diary of all your outdoor adventures.

Most recently, the PeakVisor App has included up-to-date weather reports at any destination. Plus, we've been hard at work adding the details of hundreds of mountain huts and camping options.

You can also use our Hiking Map on your desktop to create .GPX files for routes to later follow on the app.

Here is the most famous hike in Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park, where you can loop together the park’s highest peak—Saint Mary—with its most iconic feature, the Wilpena Pound natural amphitheater. The area is significant to the local Adnyamathanha Aboriginal people; Ikara means “meeting place.” The name Wilpena comes from an Aboriginal word meaning “cupped hand” or “a place where fingers bend.”

The hike begins at the Wilpena Pound resort area. Because Saint Mary Peak is important to the Adnyamathanha creation (Dreamtime) story, hikers are requested only to go as far as the saddle. It’s also recommended to complete the 18 km (11 mile) loop counterclockwise to ascend steeply and descend slowly. Here’s a blog post on the hike with everything you need to know.

If you can’t do this strenuous hike, there are other options. The crater itself is so interesting that aerial flight tours are quite popular; there’s a small airstrip in the town of Wilpena Pound, where this hike starts. Needless to say, we always prefer self-powered adventures in the mountains at PeakVisor.

Alligator Gorge is one of the most famous hikes in SA. It’s in Mount Remarkable National Park, on the southern end of the Flinders range. The hike, known as the “Ring Route,” is a loop that circumnavigates the gorge’s most striking features, including the Narrows and the Terraces. The Narrows is a long section where the gorge constricts to just a couple of meters across.

Expect to see plenty of wildlife, especially if you head out in the morning or evening, which are the best times to experience this hike. It’s often the only time you’ll be able to go, as the sun will boil you alive once it reaches over the canyon walls.

It’s not the longest hike, at about 8.4 km, and you should be able to finish within a few hours.

Deep Creek National Park, occupying the Mediterranean heathlands of the Fleurieu Peninsula, is one of SA’s coastal treasures. The best way to experience the park is the 12-kilometer (7.5-mile) Deep Creek Loop, which winds along the rugged coastal cliffs with excellent views of the surrounding shrubland and Kangaroo Island, about 10 km (6 miles) offshore.

Iconic native Australian species like banksias attract colorful birds like the New Holland honeyeater and superb fairy-wren (look for males in breeding plumage, with their striking blue head; breeding lasts through spring and summer).

After Deep Creek NP, Kangaroo Island is just a 45-minute ferry ride away. The ferry leaves Cape Jervis several times a day.

Witjira National Park is perched at the far northern border of South Australia and is home to the famous Dalhousie Hot Springs. The springs form a desert oasis with dozens of pools ranging from 38-43℃ (100–109°F). There’s not too much hiking involved here; the Dalhousie Hot Springs Loop is a 3 km ramble that accesses the various springs starting from the campground.

Like the Wilpena Pound, the springs are featured in Aboriginal Dreamtime stories within the Wangkangurru and Southern Arrernte cultures. The springs are best experienced in the winter months; it’s simply too hot for this desert locale in the summer.

The Heysen Trail is one of Australia’s premier long-distance through hikes, stretching 1,200 km (750 miles) across the state from south to north (or vice versa). You’ll experience all SA has to offer on this trail, from the coastal heathlands of Deep Creek NP to the temperate forests of Mount Lofty, all the way to the craggy dry forests of the Flinders Ranges. It’s not all wilderness, though. For a bit of culture, the route also passes through astonishing pastureland and wine country, as well as historic country towns.

Fortunately, the trail is divided into many sections—about 61 in total—so it’s easy to do a day hike as well. You’ll find Heysen trailheads regularly throughout the route. The Heysen Trail is only open during the fall, winter, and spring (April to October) to avoid fire danger season.

The best way to experience Kangaroo Island is on foot, along the Kangaroo Island Wilderness Trail. This five-day trek traverses 66 km (41 miles) through Kangaroo Island and showcases the famous koala-dense Eucaplypt forests, beaches, coastal cliffs, and even freshwater lagoons. It’s best to go in the fall, winter, and spring to avoid fire danger season.

The 19-20 bushfires severely impacted the trail, closing it for several years. The latest news is that, as of December 2023, the trail is once again open to trekkers without a guide.

People don’t really visit SA to explore its sleepy towns. The towns serve as a gateway to nature. Nevertheless, there are a few locales worth a visit, and in the case of Adelaide, necessitate a visit if you want to explore the state.

Another thing to note is that by and large, the towns worth visiting are along the coastal regions, often near Adelaide. The Outback towns are, well, perhaps a bit underwhelming from a tourism perspective.

All things considered, Adelaide is a charming capital city with a pleasing blend of Victorian buildings and green space. The city’s layout is notable, with parklands surrounding the central banking district (downtown). It’s also built on a grid system, which is remarkable if you’ve spent enough time sitting in Sydney traffic.

Adelaide also has a thriving food and wine scene thanks to its proximity to wine regions like the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale, as well as plenty of other fresh produce.

The city is fantastic for outdoor enthusiasts, and not just because of the central parklands; it’s bordered by the Mount Lofty Ranges to the east and the coastline to the west. The Waterfall Gully to Mount Lofty Summit trail is a favorite, where you can see across the city and out to the coast. The beaches along the coast range from bustling boardwalks to the quiet sands of Henley Beach and Semaphore. It’s worth noting that because of the southern influence, the water temperatures are somewhat colder than Australia's east and west coasts.

Just south of Adelaide on the Fleurieu Peninsula, McLaren Vale is one of SA’s leading wine regions. The area’s Mediterranean climate makes it among the best in Australia to produce wine. It’s best known for Shiraz, but McLaren Vale also produces high-quality Grenache and Cabernet Sauvignon, among others. Many vineyards here are small, independent producers focused on sustainable practices. There are over 80 producers in the immediate area.

Like many wine towns, there is a plethora of artisanal cottage industries here, from local olive oils to cheese. McLaren Vale also has trails, road cycling, and ocean access that will be agreeable to outdoor enthusiasts.

Mount Gambier, located in southeast SA near the Victoria border, is the second largest town in SA, though it’s mostly known for its unique volcanic landscape. The city sits atop an extinct volcano, with one of the craters famously forming the Blue Lake (Warwar), which changes color dramatically from grey to a vivid cobalt blue each summer.

The Umpherston Sinkhole and the Engelbrecht Cave are also popular attractions, the result of water slowly eroding limestone over millions of years. The Umpherston is replete with a garden oasis at the bottom. For the experienced—or daring—these limestone caves are particularly popular with divers, who explore the clear, deep waters and surreal rock formations.

The summit of Mt. Gambier is nearby and requires a short but steep scramble to the top, where the Centenary Tower offers views stretching more than 100km (60 miles) across the limestone coast.

The city itself offers a few historic buildings and galleries, though the surrounding nature is more exceptional.

Clare is another historic wine region about 120 km (75 miles) north of Adelaide. Contrary to McLaren Vale to the south, Clare is best known for its crisp Rieslings and cool-climate wines. The winemaking heritage goes back to the 1850s and features a mix of family-run wineries and small producers; the wines here are even more artisanal than McLaren Vale.

The region’s popular Riesling Trail offers a scenic route for cyclists and walkers to explore the vineyards and olive groves. The town of Clare is very historic by Australian standards, with stately stone buildings and wide streets.

Explore South Australia with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.