Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

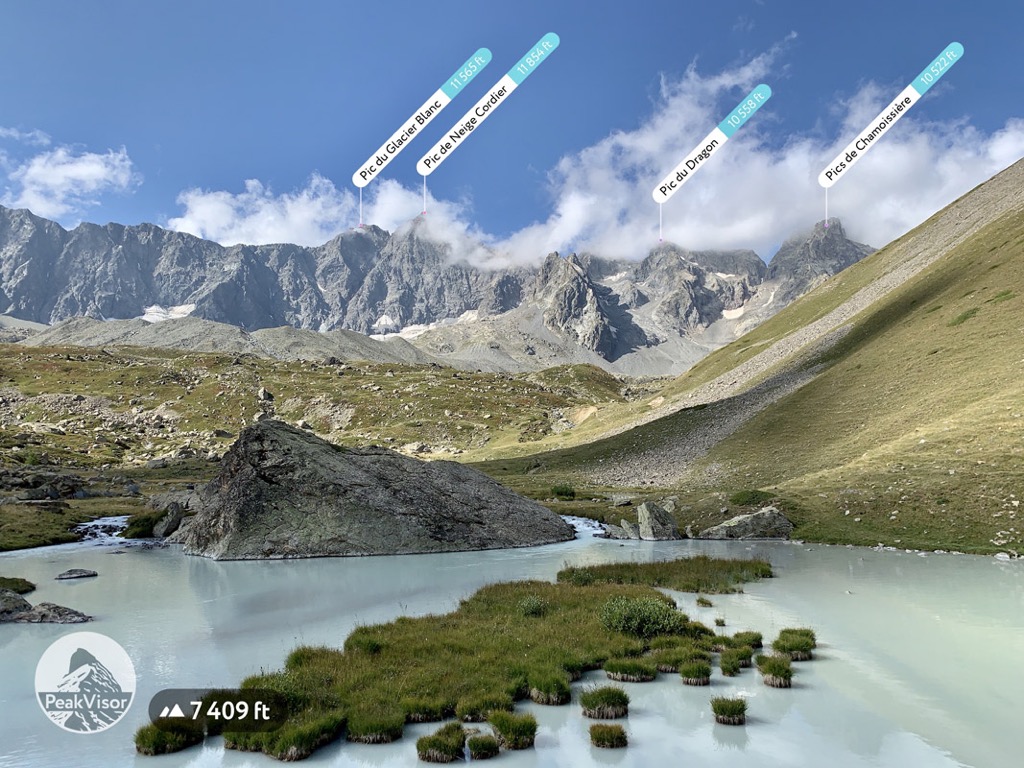

Hautes-Alpes is a governmental department in the Western Alps of Southeastern France. The department forms the northern boundary of Provence-Alpes-Côte D'Azur and shares a border with Italy. The Massif des Écrins is the home of the Barre des Écrins (4,102 m / 13,458 ft), the tallest and most prominent (2,043 m / 6,073 ft) peak. Before the annexation of the Savoy in 1860, this was the tallest peak in France and the only one above the 4,000-meter milestone, thus the name ‘Hautes-Alpes’ (High Alpes). There are 2,184 named peaks within the region, with 200 named glaciers nestled amongst their high bowls and faces. Currently, the department is the third least-populated in the country and home to two stunning parks: Parc National des Écrins and Parc Naturel Régional du Queyras.

Hautes-Alpes is one of the highest departments in France, with an average elevation of over 1000 m (3,300 ft), with one peak reaching above 4,000 m (13,123 ft): the Barre des Écrins (4,102 m / 13,458 ft). The Barre is the tallest mountain in France outside of the Mont Blanc Massif and is the most southerly 4,000-meter peak in Europe.

The two main alpine groups are the Écrins and the Queryras. The Écrins fall within the Dauphiné Alps subrange, while the Queryas are part of the Cottian Alps, both of which are in the Western Alps. The two massifs are separated by the deep valley stretching between Gap and Briançon.

Unlike the Queryas, the Écrins are heavily glaciated above 3000 meters (10,000 ft). Over 200 named glaciers lurk in the shadowy abscesses of these jagged peaks. Many glaciers once flowed below 2400 meters, although only a few dirty remnants remain. The year 2022 saw a 6-7% reduction in the total mass of the ice sheet, the result of decades of drought and a viscously hot summer. Vast moraines remind visitors of recent (19th century) glacial termini throughout the Écrins.

Only two towns within the department have more than 10,000 residents: Gap and Briançon, the prefecture and subprefecture, respectively. With approximately 140,000 people, the department is the third least populated in France. Due to several major ski areas, the number of skiers on any given day is a sizable percentage of the total population.

A central feature of the southern Hautes-Alpes is the Lac du Serre-Ponçon, one of the largest artificial lakes in Western Europe. The lake is a result of the damming of the Durance River. First proposed in the 19th century after disastrous floods destroyed villages downstream, the dam was constructed between 1955 and 1961. The valley slowly filled with water to become the Serre-Ponçon. Today, it irrigates 1,500 square kilometers (580 sq mi) of farmland, generates 2000 MW of hydroelectric power, and provides many recreational opportunities.

The Hautes-Alpes department shares fundamentally similar geology across the Écrins and the Queryras. However, there are some local differences as well.

The entire European Alps was created by the Alpine Orogeny, which occurred between 64 and 2.5 million years ago. The orogeny results from the African and Indian plates colliding with the Eurasian plate, forcing the crust upwards. In many places, the orogeny is ongoing - namely, the Himalayas, because the Indian plate has only recently collided with Eurasia and continues to exert force on the crust. Even at a few tens of millions of years old, the Alps are still young, hence the towering, jagged peaks and low valleys.

Every valley within the department has been shaped by glaciation to some extent. Glaciers have ebbed and flowed over the past 2.5 million years. In addition to the sculpted valleys, you can see large boulders - known as glacial erratics - throughout the Durance Valley near Gap.

Yet, the geology of the taller Écrins massif differs from the smaller Queryas. In the Écrins, we see the presence of the basement crystalline layer. This isn’t nearly as complex as it sounds. The basement layer is an old, thick belt of rock lying beneath newer deposits of sandstone, limestone, etc. It consists of igneous and metamorphic rocks rather than the sedimentary deposits closer to the crust’s surface. Often, the basement layer is granite, like that found in the Alps.

The highest peaks of the Alps are granite because there was enough force to expose the basement layer. The Massif des Écrins, Massif du Mont Blanc, and the Matterhorn are examples of high granite peaks of the Alps. Meanwhile, the Queryas consist mainly of limestone, dolomite, basalt, and glossy schist.

Rock climbing is one of the primary ways this impacts the mountain folk of the Hautes-Alpes. The Écrins have excellent granite alpine routes, while the Briançonnais valley hosts legendary limestone sport climbing.

Music Project Mountain by Kristian Skybound (c) copyright 2018.

Flora and fauna are consistent throughout the mountainous regions of the department, but the Écrins have the region’s most intact alpine ecosystem. It is a national park under complete protection - no hunting, pets, or fires. The area was also spared from a significant mining boom. Larch forests generally thrive below 2400 meters, with rock and ice fields above 3000 meters.

The old-growth larch forests and mid-alpine meadows of the Hautes-Alpes are enchanted. Here, you will find chamois, ibex, wolves, lynx, golden eagles, bearded vultures, tawny vultures, owls, rock ptarmigan, tetras, ermines, hares, foxes, squirrels, marmots, and many other animals. As of 2023, wildlife biologists are tracking three wolves that have made their home in the forest above La Grave and 40 breeding pairs of Golden Eagles. Black crows, a.k.a. Alpine Chough, soar amongst the rocky spires and peaks.

The region is home to more than 2,500 plant species. Well-known species include edelweiss, blue thistle, and génépi (used to make a hard liquor called a ‘digestif’). Wildflowers are rampant throughout the meadows, especially where livestock graze and fertilize the ground.

However, the most remarkable plant is the larch (meleze, in French) tree, which dominates the forested terrain throughout the region. The larch is a pine tree that loses its needles in the winter, creating a radius of highly acidic soil and preventing other plants from growing. This gives the forests a cathedral-like ambiance - and makes for excellent tree skiing.

Anatomically modern humans probably arrived in the region around 40,000 years ago. However, limited evidence of these early pioneers exists.

More recently, the area was inhabited by various Celtic groups until the arrival of the Romans around 2100 years ago. Romans quickly constructed roads throughout the region, and Gap became a small population center fortified by thick walls.

The middle ages proved difficult for the region as religious wars took their toll. Gap and Briançon remained relatively autonomous throughout the period and were not incorporated into the French state until the 16th century. Hautes-Alpes is one of the original departments designated during the French Revolution. At the time, Chamonix had not yet been annexed, and the Écrins were the tallest mountains in France - hence the name ‘High Alps.’

The Écrins jagged peaks have intimidated mountaineers for decades. La Meije (3,984 m / 13,071 ft) was the last major summit of the Alps to see an ascent. It wasn’t until August 16, 1877, when Boileau de Castelnau and Pierre Gaspard made the first ascent, nearly 100 years after the first ascent of Mont Blanc (4,809 m / 15,780 ft).

Department-wide, the population declined from the 1700s until about the 1960s as farmers left for urban areas. However, the region has since witnessed consistent population growth as recreational and economic opportunities have blossomed.

Like most places in rural France, the primary economic driver was agriculture - mainly sheep and goat herding on the vast alpine pastures. The smaller villages have steadfastly clung to these roots. The terraced hillsides are still visible in many parts of the department, and you’ll likely see goats, sheep, and gardens scattered throughout the mountains.

Today, the department’s primary industry is outdoor tourism. Several ski stations shuttle skiers as high as 3600m. Mountain biking has become popular, with most ski resorts running their lifts in the summer for bikers. Thousands of rock climbing routes exist, with the highest concentration around Briançon. Road cycling is also famous - the Tour de France generally bisects the Hautes-Alpes. Other recreational pursuits include hiking, snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, snow-kiting, paragliding, and mountaineering.

The department remains one of the least populated in France, and most ski resorts are pleasantly non-commercial. Gap is the largest town at 40,000 people; Briançon is the only municipality larger than 10,000. Embrun has 6,000 residents. Most other settlements are villages, some of which have remained magnificently rustic.

Hautes-Alpes is a hiker’s paradise, with trails branching off throughout the department. Because of the region’s massive vertical relief, most hikes are relatively strenuous. In addition to thousands of day hikes, there are several famous multi-day hikes, such as the GR-54.

Belvédère des Curattes: An easy hike outside the village Chorges, this 4.2 km (2.6 mi) loop offers exceptional views of the Lac du Serre-Ponçon with only 177 m (580 ft) of climbing.

Lac Sainte-Anne: Experience the Queryas with this exquisite, moderately challenging out-and-back. The trail starts in the village of Fond de Chaurionde and climbs 481 m (1,578 ft) to the lake at 2,400 m (7,874 ft). The out-and-back is 6 km (3.7 mi) long and is busy during summer.

Lac de l'Eychauda: Experience one of the best day hikes in the Écrins with this challenging 11.4 km (7 mi) out-and-back. Be ready to climb 825 m (2,706 ft) to an elevation of 2,500 m (8,202 ft), with a spectacular view of the surrounding peaks and the Glacier de Seguret Foran, which feeds the lake. The trail ascends from the hamlet of Chambran near Pelvoux.

Two notable backpacking routes take visitors around Hautes-Alpes: the GR-54 and GR-50. GR stands for Grand Randonee in French, which means ‘long hike.’ In addition to these established routes, it’s easy to link various trails and make overnight trips. You have limitless options between wild camping and staying at refuges.

Traversing through Hautes-Alpes and neighboring Isere, this 188.6 km (117 mi) route is not for the faint of heart. Most hikers take about a week to finish, give or take a day. Plenty of accommodation exists on the route in the form of huts, but there are plenty of opportunities for wild camping if you don’t mind carrying the extra weight. With 12,000 m (40,000 ft) of elevation gain, every ounce makes a difference.

Start in the town of Bourg d’Oisans and traverse through the heart of the Écrins in a loop back to Bourg. The route is exceptionally strenuous and passes as high as 2,800 m (9,186 ft), so the season is usually July, August, and September. June can also work if you’re prepared to cross snow.

Most hiking is in a national park, so no pets are allowed, and wild camping is restricted to one night in the same place. The Écrins is wild, beautiful, and free to enter, but many rules are in place to protect the environment. Be aware of and follow these rules during your trip.

The GR-50 is longer than the 54, but the hiking is mellower (although still highly challenging). At 371 km (230 mi), expect to spend at least two weeks on the trail. The total elevation gain is 19,000 m (62,000 ft). The route only ascends to 2,400 m (7,874 ft), so the season is longer - you could probably do this route anytime between May and October without hitting too much snow.

Like the GR-54 - and many other European backpacking routes - you can carry camping equipment and sleep outside or utilize a massive network of huts.

The route doesn’t pass through the heart of the Écrins, instead taking a wider loop around the park's outskirts and above the Durance Valley. The trail begins in Bourg d’Oisans, meandering above Gap and the Lac du Serre-Ponçon. The loop travels up the Durance Valley, above Briançon, then back west toward La Grave and eventually Bourg.

Hautes-Alpes is home to some of the best resorts in the world. Most of these resorts are smaller and less commercialized than their peers in other regions of France. Here are some of the most special domains:

Serre Chevalier Ski Area is incredible. Many wide pistes, freeriding itineraries, hike-to terrain, and a lift system stretching over several peaks set this resort apart. The resort comprises several base villages, including Briançon, Chantemerle, Villeneuve-la-Salle, and Le Monêtier-les-Bains. It is the largest ski resort in Provence-Alpes-Côte D'Azur, with more than 250 km (155 mi) of slopes and more than 60 ski lifts, which reach 2,800 m (9,186 ft). The tree skiing amongst ancient larch forests is incredible. It’s some of the best in Europe when there is snow.

Speaking of snow, there’s usually plenty of it. Serre Chevalier gets storms from multiple directions. They also have extensive snowmaking on the pistes. Another aspect of Serre Che is the access from Briançon, which is unique among European ski towns. The historical Old Town dates back 400 years. The restaurants and accommodation are affordable. There’s none of the glitz and glam of other ski resorts — all of that exists in the other base villages. Briançon is a bit rough around the edges in a way that I appreciate.

Montgenèvre Ski Resort is on the border with Italy at the tip of the Hautes-Alpes. The main feature is the namesake Col du Montgenèvre pass of 1,860 m (6,102 ft) and its surrounding mountains with many slopes and freeride descents in an uncrowded setting. Enjoy epic views of one of the most prominent peaks in the Hautes-Alpes, Mont Chaberton (3,131 meters / 10,272 ft).

Montgenèvre is also the only French resort connected to one of the most extensive ski areas in Europe and the world. The Via Lattea (“The Milky Way”) includes the Italian resorts of Claviere, Sestriere, Sauze d’Oulx, San Sicario, and Pragelato, with more than 400 km of slopes and 70 ski lifts. Montgenèvre itself has 110 km (68 mi) of slopes and 30 ski lifts. The Montgenèvre (Via Lattea) season is generally from early December to mid-April. The resort’s advantageous geographic location makes it one of the snowier resorts in the Alps.

Those looking to poke the sleeping dragon of fate need not look further than the hamlet of La Grave. This sleepy cluster of villages is perched in a deep valley demarcating the north end of the Parc National des Écrins. There is one lift, ‘the Téléphérique,’ to 3200 m (10,500 ft), and another drag lift to 3600 m (11,811 ft). No trails exist on the mountain; every descent is off-piste and requires a high level of skiing and route-finding.

The Téléphérique was constructed in the ‘70s, allowing hikers to go up and look around at the Glaciers de la Meije and boost the economy. In the ‘80s, pioneers began exploring the steep slopes on skis. The ‘90s and ‘00s saw a popularization of extreme skiing and increased traffic in La Grave. Yet, at present, the village remains authentic, and the slopes are still relatively empty.

No luxury accommodations exist in La Grave. There are no nightclubs or cinemas. The village consists of a few restaurants, gear shops, hotels, and a small market. Even the slightest injury on the mountain necessitates a helicopter rescue if you cannot ski down. It’s not everybody’s cup of tea, but this place rules for those serious about their skiing.

Several small ski stations are perched throughout the valleys of the Queryas. Abriès, also known as Abriès-Ristolas, boasts the region's second-highest lifted skiable vertical of 900 m (2,953 ft) and the best opportunity for exciting freeride descents. Be warned; the lift infrastructure is dated, and you’ll be subjected to multiple slow chairs and draglifts to reach the top. On the other hand, the non-commercial vibe of Abriès and the other resorts of the Queryas is priceless.

While most of the slopes are rated intermediate, the broad north-facing forested terrain down to the hamlet of Valpreveyre from the 2,463 m (8,087 ft) summit of Gilly is enticing for freeride powder seekers. A bus brings skiers back to the resort every half hour or so.

These descents off the backside are not patrolled or controlled for avalanches, and although it’s mostly tree skiing, several features could pose an issue on the wrong day. Steep chutes and faces lurk amongst the trees. Route finding will also be challenging. I recommend bringing a full avalanche kit and some friends who know the descents - you’ll have more fun that way. If you prefer sunnier freeride descents, you can opt for mixed open and forested terrain that leads down to Ristolas.

Gap is the highest prefecture in France, at an altitude of 735 m (2411 ft). Located at the foot of the mountains, this is the largest town in Hautes-Alpes and is a gateway to the Écrins; there is a visitors center right in town. Gap is also close to the gorgeous Lac du Serre-Ponçon. You can spend mornings in the mountains and afternoons by the beach. Due to the Mediterranean influence, Gap is often sunny; there are nearly twice as many mean sunshine hours per year as in Paris, for example.

Like many towns in France, history buffs will enjoy Gap. The old town boasts several attractions, including the 18th-century facade of the town hall with its wrought-iron balconies and the 19th-century Neo-Gothic Notre-Dame-et-Saint-Arnoux cathedral, featuring a 70-meter high bell tower porch and a magnificent organ. The Gap Departmental Museum, dedicated to archaeology and art history, is also a place of interest. Visitors can marvel at exhibits such as the white and black marble mausoleum of the Duke of Lesdiguières.

Every July, Gap hosts the International Folk Dance Festival, a significant cultural event that attracts visitors from all over the world. However, the town has retained its identity in the age of second homes and Airbnb; over 80% of homes are primary residences.

Briançon, the highest city in France, sits at an altitude of 1,326 meters at the convergence of five valleys. This city is a mecca for mountain enthusiasts and tourists coming to see the astonishing Old Town. With incredible access to climbing and skiing, many high mountain guides are based here.

The original settlement was fortified by French military architect Vauban in the 18th century. This central Old Town is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its remarkable fortifications built between the 18th and 20th centuries. A tour will take you through the Vauban citadel, the fortified castle, and the surrounding forts, including Salettes, Trois Têtes, and Randouillet.

Architecture enthusiasts can explore the 18th-century collegiate church of Notre Dame, the 14th-century Cordeliers church, old houses lining the steep, narrow streets, and the charming Place d'Armes square surrounded by pretty, colorful Provence-style facades, fountains, and sundials.

Briançon has since sprawled over a wide swath of the surrounding valleys. The base villages of the Serre Chevalier ski area extend to the northwest, while Montgenèvre branches off to the northeast. The newer constructions are not particularly sightly compared to the Old Town, but Briançon still has charm. Even though it has access to an excellent ski resort and climbing and is rich in history, Briançon has remained affordable.

Explore Hautes-Alpes with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.

top50

ultra

glacier

alps-4000ers

france-ultras

top50

ultra

glacier

alps-4000ers

france-ultras