Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

The Vanoise Massif, one of the preeminent alpine destinations in the world, sprawls across the Western Alps region of the department of Savoie, France. The massif is one of the centers of mountain life in the Alps; the Vanoise National Park protects the high alpine peaks and glaciers of the central region, while many famous ski resorts, such as Tignes, Val d’Isère, Courchevel, and Méribel, access the perimeter. With plenty of high alpine terrain, the Vanoise is one of France's most heavily glaciated regions, along with the Mont Blanc Massif and the Écrins Massif. La Grande Casse (3,895 m / 12,648 ft) is the highest and most prominent peak.

The Vanoise Massif is magnificent. The Vanoise National Park is France’s first, created in 1963 to protect the Ibex, which had been hunted to near extinction. Naturally, the park protected everything else as well: flora, fauna, and landscapes. Combined with the Italian Gran Paradiso National Park, the 1250 ㎢ (483 sq. miles) protected region is the largest in the Alps.

No mountain biking is allowed in the park, but hikers and climbers will find pristine natural spaces, vast glaciers, classic mountaineering routes, and (relative) solitude. Populations of Ibex have recovered significantly since the 1960s.

However, the region is also exceptional in that it straddles the extremes of French mountain culture, including the unbridled development of the 1970s and ‘80s. Each week in the winter, hundreds of thousands (not an exaggeration) of skiers descend upon the dozens of ski domains to enjoy a white holiday. Les Trois Vallées alone offers an estimated 260,000-per-hour skier capacity across 183 lifts.

The perimeter of the Vanoise is almost entirely developed by ski resorts, including the largest in France: Les Trois Vallées. The Espace Killy (Tignes, Val d’Isère) and Paradiski (Les Arcs, La Plagne) are nearly as big. All told, thousands of kilometers of pistes snake along the slopes of the Vanoise. While exact measurements are difficult, the Vanoise is likely the most developed ski region in the world.

The ski towns throughout the valleys range from medieval alpine villages (Bonneval-sur-Arc) to chic, modern resorts (Courchevel) to concrete monstrosities (Val Thorens).

The Vanoise is bordered by the Tarentaise Valley to the north and the Maurienne Valley to the south. Most of the region is drained by the Isère River, which runs along the Tarentaise Valley. Most of the Vanoise’s ski areas are also located within this vast valley and its offshoots.

The Alpine Orogeny, which occurred between 64 and 2.5 million years ago, created the entire European Alps. The orogeny results from the African and Indian plates colliding with the Eurasian plate, forcing the crust upwards.

In many places, the orogeny is ongoing - namely, the Himalayas, because the Indian plate has only recently collided with Eurasia and continues to exert force on the crust. Even at a few tens of millions of years old, the Alps are still young, hence the towering, jagged peaks and low valleys. The mountains have not had time to erode, and the valleys have not filled with sediment.

The orogeny was completed around the Vanoise about 15 million years ago. Some peaks still show an annual rise of up to 2.5 mm, though geologists speculate this is due to the rock rebounding from the weight of melted glaciers.

Since then, successive ice ages have been the primary geological driver of change. At times, the lowest valleys surrounding the Vanoise filled with ice. Other times, the highest summits have seen little to no glaciation. These ice movements have shaped the region’s lower valleys while the ice continues to scour the higher alpine valleys.

Interestingly, the Vanoise’s rock composition differs drastically from France's other two largest massifs. While the Écrins and Mont Blanc comprise a granite batholith, the Vanoise features gypsum, sandstone, quartzite, shale, mica schist, gneiss, and other rocks.

The geology is complex. Essentially, numerous geological phenomena over the past billion years created different rock layers. Having long been covered up, the recent Alpine Orogeny thrust these layers to the surface, forming the patina of rock we see today.

Vast fir, spruce, and larch forests thrive below 2000 meters, with rock and ice fields above 2800 meters. The massif’s lowest-elevation forests consist of deciduous tree species such as beech, alders, maples, birches, service trees, willows, and laburnums.

Of the thousands of plant species, the most famous include edelweiss, blue thistle, and génépi (used to make a type of hard liquor called a ‘digestif’). Wildflowers are rampant throughout the meadows, especially where livestock graze and fertilize the soil.

The forests and alpine meadows of the Vanoise Massif are enchanted. Here, you will find chamois, ibex, wolves, lynx, golden eagles, bearded vultures, tawny vultures, owls, rock ptarmigan, tetras, ermines, hares, foxes, squirrels, marmots, and many other animals. Black crows, a.k.a. Alpine Chough, soar amongst the rocky spires and peaks. Of particular importance is the Ibex, which the park was originally designated to protect.

The alpine slopes are the wildest spaces on the Vanoise Massif. The surrounding valleys are highly developed. Ski slopes (winter) and livestock (summer) dominate the median altitude. Fortunately, the National Park protects the majority of the massif’s most sensitive, high-alpine zones.

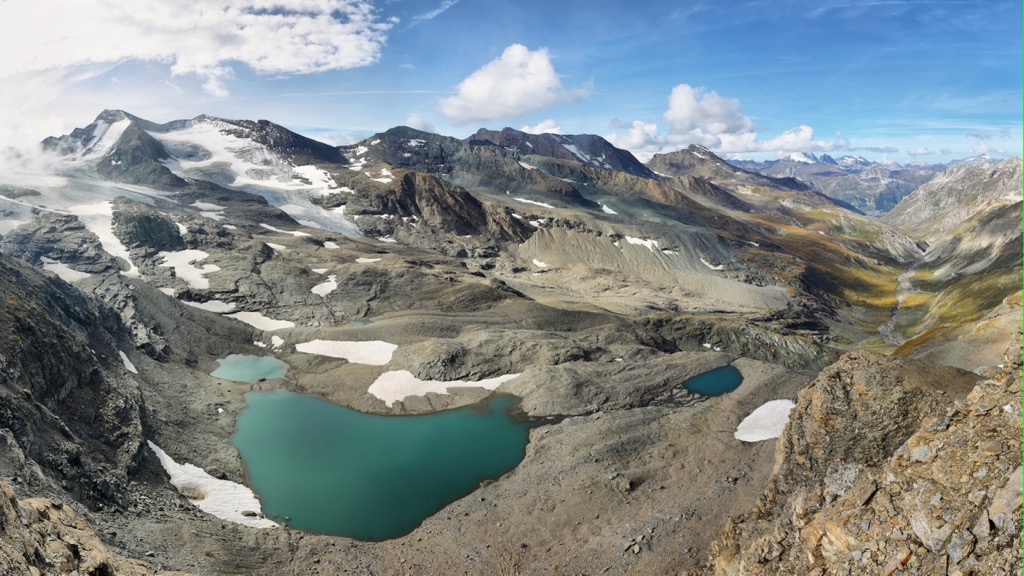

However, no park boundary can protect the region from climate change, which has been aggressively melting glaciers for the last 150 years (80-90% mass reduction, 50% surface area reduction). Because the park has no peaks above 4000 m (13,000 ft), few glaciers will remain here by 2050. That’s quite astonishing when you see how big they are, even in 2023.

Anatomically modern humans probably arrived in the region around 40,000 years ago. However, limited evidence of these early pioneers exists.

Celtic tribes, specifically the Gauls, occupied most of pre-Roman France. In the valleys of the Alps, the Romans subdued the Gauls by 125 B.C. After the fall of the Roman empire and throughout the Dark Ages, these valleys passed through the hands of many rulers.

In the 14th century, the House of Savoy began a 500-year rule of the region stretching from the northern Italian plain to Geneva and south to Nice. It became known as the Duchy of Savoy for most of this time and was a formidable state.

In 1563, the House of Savoy moved the capital from Chambery, their ancestral homeland, across the Alps to Turin. More importantly, the Alps proved too potent a geographical barrier for Italy - the region of Savoy west of the Alps increasingly identified with French culture. France invaded during the Revolution and formally annexed the state in 1860.

The Annexation ultimately resulted from political maneuvering on both sides of the Alps. Italy needed French support for unification in the face of the waning Holy Roman Empire. Recognizing their tenuous grip on the region of Savoy from across the towering alpine ridge, they offered it to France in exchange for support. Italy maintained control of the land south and east of the alpine rim, while the northern/western side became French.

The region’s inhabitants were generally pleased by this arrangement. The French Savoie has its own culture - known as ‘Savoyard,’ in French - but this culture is drastically more French than Italian.

In 1924, Chamonix, France, hosted the Winter Olympics. The following decade saw the promotion of skiing and winter vacations as the ultimate vacation. The industry, known as ‘white gold,’ exploded throughout France and the Western world. It was a way for economically depressed mountain towns to overcome the growing trend of urbanization. Opened in 1930, Val d’Isère was the first large-scale ski area around the Vanoise.

WWII set the industry back by decades. Still, by the ‘60s and ‘70s, the construction of entire ski towns was in full swing. Les Arcs, Val Thorens, and La Plagne are just a few of the resorts built during this time.

The Vanoise stepped onto the world stage when Albertville hosted the 1992 Winter Olympics. The resorts stand to weather climate change better than most in the Alps. The Vanoise is one of the most snow-sure regions of the Alps (Bonneval-sur-Arc is, on average, the snowiest resort in France), and many resorts reach above 3,000 m (10,000 ft).

Nevertheless, the megaresorts here have come under fire for being too commercial to provide a satisfying holiday for many European tourists. Some folks have sacrificed the hundreds of kilometers of perfectly groomed piste, heated chairs, luxury hotels, and reliable snow for smaller resorts that offer a more authentic experience.

Here, we have a relatively easy hike connecting two picture-perfect French villages. The hike is about 5 km (3.1 mi) and only covers 237 m (778 ft), which is not strenuous for the French Alps.

Starting in the village of Bonneval-sur-Arc, head up along the river until you reach the petite and lovely hamlet of Écot. If you think Bonneval-sur-Arc is small, wait until you get to the hamlet. Along the way, you’ll pass happy cows, wildflowers, and the Arc River, filled with turquoise glacial runoff. You’ll also pass other people; this is a reasonably popular hike. However, there are fewer people overall than in the numerous resort towns of the Tarentaise Valley.

From the ski village of Pralognan-La-Vanoise, hikers can explore a series of beautiful alpine lakes using a portion of the GR-55, a 160 km (100 mi) trail cutting across the Vanoise.

It’s possible to take a lift to gain some elevation or hike from town. The hike is relatively strenuous, with around 900 m (3000 ft) of elevation gain. The distance will vary depending on how far you choose to venture. Some hikers stop at the Lac Long and Refuge du Col de la Vanoise, while others head further. Nevertheless, it will be at least 12 km (7 mi) round-trip.

In addition to the stunning lakes, the highlight is the views of La Grande Casse and its glaciated west bowl.

You can find these hiking trails in PeakVisor:

Sitting at the end of the Tarentaise Valley, Tignes and Val d'Isère are among the finest ski resorts in the world. Each features 150 km (90 mi) of piste trails and seemingly endless off-piste. A combined lift pass is available, but patrons can save by buying a pass to just one or the other. Snowfall and elevation are abundant, and modern lifts dominate the infrastructure. Glacier skiing still exists at Tignes on the Grande Motte, but the relatively small glacier atop Val d'Isère’s Montets lift is mainly melted (as of 2023).

Though Tignes’ main village stands at 2,100 meters, its aesthetics don’t match the picturesque and charming resort village of Val d'Isère. If you can ignore the presence of broad, towering apartment structures, the raw alpine terrain, the cost of dining, and lackluster nightlife, you will begin to appreciate pure skiing. An impressive selection of intermediate trails and an expanse of off-piste freeride terrain compete with the infamous Grands Montets. Expert skiers will relish the expansive alpine bowls at both resorts and the steep couloirs at Tignes.

Tignes is noticeably less crowded than Val d'Isère. However, both resorts are on the radar of powder skiers from all over the region and get hammered on powder days. Val d'Isère’s pistes are unbearable during the six weeks of vacation from mid-February to late March - expect on-piste moguls by noon - and the off-piste is tracked out in a morning. Both resorts are extremely expensive, especially by French standards.

Les Trois Vallées hardly needs an introduction. The resort loudly boasts its status as the world’s largest interconnected ski area, laying claim to approximately 600 kilometers (370 miles) of ski trails. The infrastructure comprises 183 ski lifts, which can ferry 260,000 skiers per hour. A team of 160 snow groomers, over 400 ski patrollers, and 3,000 ski instructors work to keep this machine running.

The area is so vast that it would take multiple articles to break everything down. The PeakVisor pages of Méribel, Val Thorens, Les Menuires, and Courchevel provide additional information.

Bonneval-sur-Arc features a relatively modest 32 kilometers of piste trails (compared to over 600 at Trois Vallées) but still provides ample terrain, especially if you're inclined to get into some off-piste powder skiing.

Surprisingly, the lower section of the ski hill caters well to beginners - not to mention lift tickets are in the range of 30 euros. You’ll understand the value when you see the price tag on everything else in the Vanoise.

However, during the heart of winter, it might be worth questioning whether this is the ideal setting for learning to ski. Bonneval is cold and dark, hence why the town never developed into a megaresort and maintained its traditional charm.

Best of all, Bonneval is France’s snowiest (or one of its snowiest) resorts. It gets storms from all directions, an advantage in the Alps, where the peaks are so large that they block weather from passing through.

Although it’s not that near to the Vanoise, Albertville stands as the closest ‘real’ town to the park. It’s about 40 minutes to Courchevel, an hour and a half to Val d’Isère, and 2 hours Bonneval-sur-Arc. On the plus side, Moutiers, the gateway to the Trois Vallées, is a mere 25 minutes away by car. Pralognan-la-Vanoise, at the doorstep of the National Park, is just an hour away.

Albertville is a pleasantly small city with an urban population of just under 40,000. Some tourists come to check out the medieval town of Conflans, with buildings dating back to the 14th century, but most are here for the mountains.

Some locals live here and commute to the mountains to be able to afford an apartment, while others come in to buy groceries at the Lidl supermarket. For tourists willing to drive, accommodation and dining are much cheaper here than in any of the ski towns embedded within the mountains.

Explore Vanoise massif with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.