Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

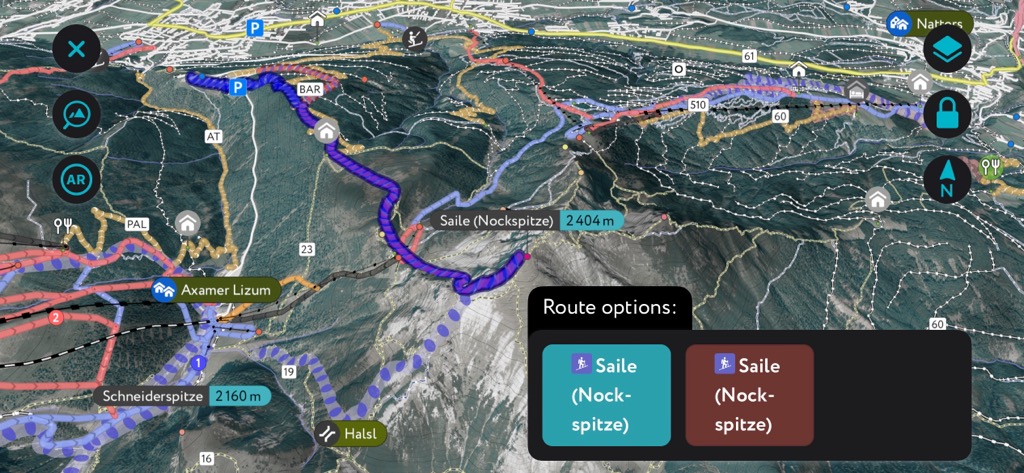

The Kalkkögel mountains lie southwest of Innsbruck in Tyrol, Austria. Known as the Dolomites of the North, the prominent limestone towers form a dramatic skyline and are widely known for hiking, via ferratas, skiing, and more. The range is a Stubai Alps sub-group with 57 named peaks. Hohe Villerspitze is the highest, measuring 3,087 m (10,128 ft), while Saile (Nockspitze) (2,404 m / 7,887 ft) has the greatest prominence (410 m / 1,345 ft).

About 30 km (18 mi) southwest of Innsbruck in Tyrol, Austria, lie the Kalkkögel Mountains. This sub-range of the Stubai Alps, part of the larger encompassing Eastern Rhaetian Alps, is called the Dolomites of the North. With limestone towers and spires jutting upwards, the range is visually striking and an outdoor recreationist’s dream.

The Inntal Valley borders the Kalkkögel Mountains to the north, the Wipptal and Stubaital Valleys to the east and south, and Senderstal to the west. Kalkkögel is separated from the Sellrain Group to the south by the Seejöchl Saddle. The Ötztal Alps neighbor the Stubai Alps to the west, and the Zillertal Alps lie to the east.

A network of hiking and climbing trails interweaves across the slopes. Due to the steep nature of these limestone peaks, most major hiking areas and summits rely on via ferratas to scale specific passages. The mountains are easy to reach from the north, east, and south, while access is more remote from the west, coming from the upper Senderstal Valley.

You’ll find some of the best skiing around Innsbruck in Kalkkögel. Resorts, cable cars, lifts, and a railroad called Olympiabahn, which has remained since the 1974 Winter Olympics, provide infrastructure to make the most of the mountains.

The main ski zones stretch along the north side of the range. The slopes of Pfriemesköpf, Birgitzköpfl, and Axamer Lizum are full of runs and lifts, comprising the Muttereralm – Mutters/Götzens Ski Resort. Mutteralm is the Kalkkögel’s most extensive resort; there is some skiing in the southwest, but it’s far more limited.

Slopes and trails can get crowded year-round. In summer, bottlenecks can form along the via ferratas, particularly on the tallest peaks like Schlicker Seespitze, Große Ochsenwand, and Marchreisenspitze.

The central part of the mountains is a nature preserve called Ruhegebiel Kalkkögel. The protected area is not open for further development of ski slopes and lifts, and hikers are asked to stay on the trail to limit their footprint.

The Kalkkögel is a sub-range of the Stubai Alps, which are part of the larger Eastern Rhaetian Alps and included in the overarching European Alps range.

The Alps formed during the Alpine orogeny, a mountain-building event that occurred as the African and Eurasian plates collided and has been ongoing since Cretaceous times. Most mountain building occurred between 65 and 2.5 million years ago, although the mountains continue to be uplifted.

However, the uplift rate no longer outpaces erosion, and the Alps are not considered a growing range. Additionally, geologists have attributed the recent uplift to a rebounding effect as the Alps spring back after the weight of the last ice sheet recedes.

The Kalkkögel and neighboring Krichdach and Tribulaun Groups are unique within the greater Stubai Alps. Most of the Stubai Alps comprise gneiss and granite, but these three mountain groups are almost entirely limestone. “Kalkstein” means limestone in German, so it makes sense where Kalkkögel got its name.

Depending on the rock and soil type, the Kalkkögel supports a variety of flora and fauna. Around mountain huts like the Adolf Pichler Hut, you can find yellow alpine poppy, edelweiss, and primroses. Alpine toadflax and Platenigl grow in dry limestone gullies. Stone pine grows in acidic silicate soils at higher altitudes and relies on pine jays to spread its seeds.

In the southeast, Scots pines handle both frost and heat and grow on calcareous, dry slopes. Their relatively sparse tree tops allow for abundant undergrowth, including orchids.

Larch meadows support many early-blooming species that prefer light, like gentians and orchids. Meanwhile, globeflowers bloom in damp places. The larch meadows and stands invite a variety of birdlife; kestrels hunt insects and field mice, green woodpeckers utilize the trees, and old larches support pygmy and rough-legged owls. Mountains in the region support other wildlife, such as golden eagles, ibex, chamois, and marmots in alpine zones.

The Kalkkögel is a short distance from Innsbruck and shares a regional history with the urban center.

The valley where Innsbruck lies has long supported human settlements. In 1180, the Counts of Andech built a settlement on what is today the historic center. Natural resources have long been used for grazing livestock, agriculture, and logging; alpine pasture farming in the region dates as far back as the 12th century.

Beginning around 1500 and lasting around two hundred years, the city served as a center for the Habsburg dynasty. Emperor Maximilian I (1459 - 1519) moved many official offices there, and his impact remains in some of the city’s best-known architecture—the Imperial Palace, the Court Church, the Golden Roof, and the Abras Castle. By 1567, the city had a population of around 5,000 people. The University of Innsbruck was founded in 1669 and is still functioning today.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the region was ceded to Bavaria. Innsbruck remained under Bavarian control until 1814 and was restored to Austria following the Vienna Congress.

The construction of railways and a shift towards industrialization brought big changes to the region. Railways arrived in the 1850s, 60s, and 80s, bringing an influx of immigrant workers, particularly from today’s Trentino-South Tyrol region.

During World War II, Nazi Germany annexed Austria. Between 1943 and 1945, the Innsbruck region suffered nearly two dozen air raids by Germany, resulting in immense damage to the city and its people.

If you’re hiking on Trail 18 above Axamer Lizum, you’ll pass by the site of an old plane wreck and a commemorative plaque. The German Luftwaffe shot a fighter aircraft carrying US Air Force bombers. The pilot attempted to steer the damaged plane to Switzerland, but after sustaining further damage, the crew jumped and deployed their parachutes. The crew landed all across the area – above the Halsl, in Kreith, Sistrans, and Rinn, on the RInnerbuhel, and the Mutterer Alm. The airmen were captured and interrogated but released after the war ended.

Since the 1920s and 30s, cable cars have propelled tourism and made mountain access easier. Innsbruck hosted the Winter Olympics in 1964 and 1988, and Olympic sites and the Olympiabahn are still open to visitors.

Kalkkögel is close to Innsbruck and home to cable cars, lifts, restaurants, and extensive trails and ski slopes. Its reputation as the Dolomites of the North precedes it, and you likely won’t be alone when visiting.

That being said, outdoor opportunities abound. Hiking trails and via ferratas lead to stunning vantage points, and all-level ski slopes are paired with backcountry powder touring. Those looking for an easy or family-oriented hike can check out Muttereralm near the base of the range.

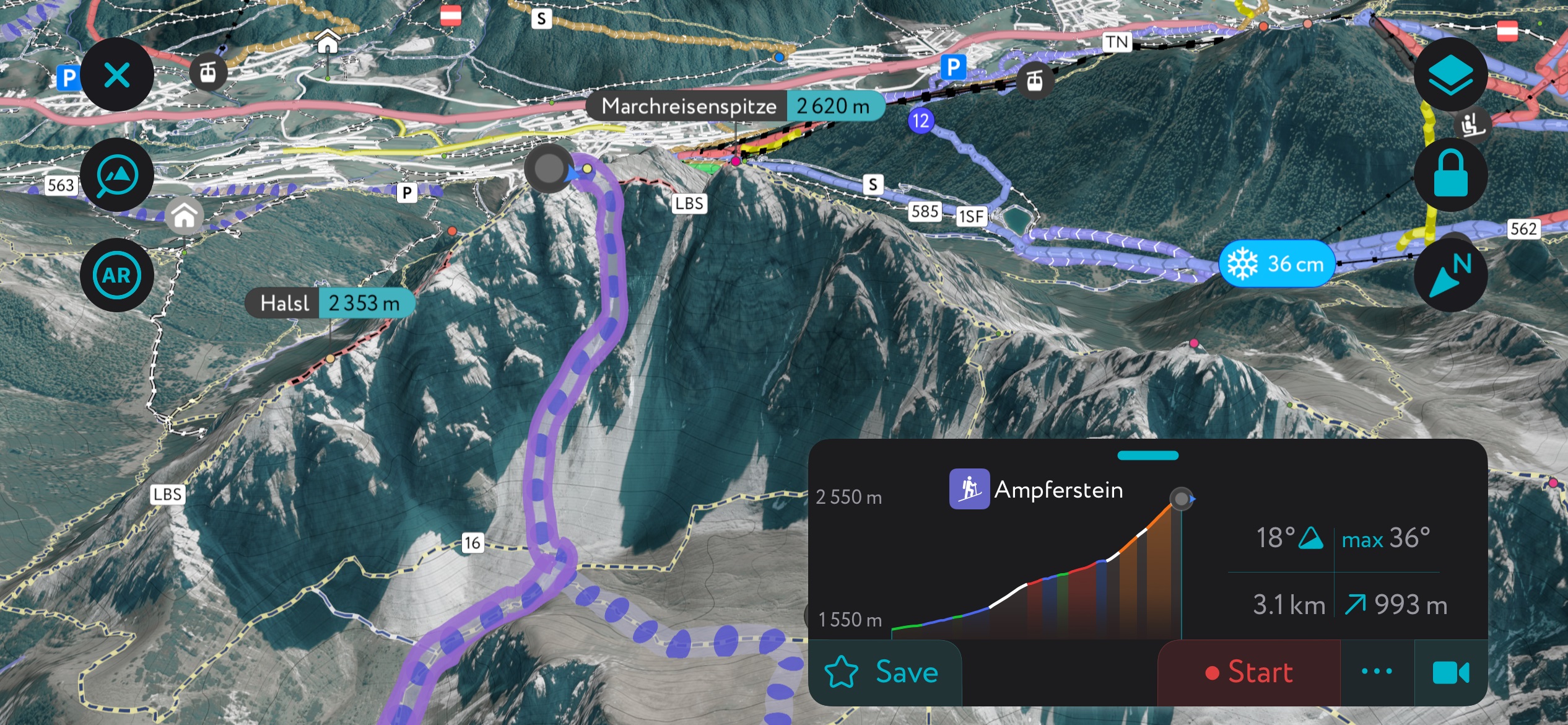

Marchreisenspitze is one of three peaks towering over Axamer Lizum. Along with the other two prominent peaks, Ampferstein and Malgrubenspitze, they are known as the Dreigsterne (“three stars”).

There are a few options for summiting Marchreisenspitze. The first and easier option is to approach from the west. The route begins by climbing Trail 18, the service road behind Axamer Lizum. It eventually turns and climbs across scree slopes to reach the Malgrubenscharte pass. From here, the route turns east along the Lustiger-Bergler Steig and climbs up the southwest side of Marchreisenspitze. This approach doesn’t feel much like a via ferrata, with only some scree scrambling and high trails along the nearly 1,000 m (3,280 ft) climb.

The second approach, from the east, is more adventurous. From the Halsl pass, the route requires more scrambling while following the via ferrata. It crosses the summit of Ampferstein before heading to the summit of Marchreisenspitze. There are some loose rock sections towards the top, so a helmet is recommended.

A third option is to make a circuit from the Birgitzkopflift chairlift at Axamer Lizum to the Birgitzkopflhaus restaurant. This lift removes around 400 m (1,310 ft) of ascent. From Birgitzkopflhaus, follow Trail 12, about one kilometer (0.6 mi) to the Halsl, and then continue on the via ferrata to summit Ampferstein and Marchreisenspitze. Descend on the far side of Marchresienspitze to the pass above Lizumer Kar.

A classic trail to do while visiting Kalkkögel is a 15.5 km (9.6 mi) out-and-back trail from the village of Grinzens to the Adolf-Pichler-Hütte. It’s moderately challenging and climbs around 980 m (3,225 ft) in elevation. This is also a good trail for mountain biking.

Although this is a popular trail, it traverses the protected area of the Kalkkögel and allows visitors to appreciate the relatively undisturbed mountain landscape. The top has incredible views, and the Adolf-Pichler-Hütte is a great spot to stop and refuel. Early alpine pioneers such as Hermann Buhl used this historic hut as a basecamp.

Axamer Lizum is the largest ski resort near Innsbruck. A new cable car opened in 2022, bringing visitors to 2,340 m (7,677 ft). There are many kilometers of slopes suited for all levels, from beginner to expert. Backcountry skiing around Birgitzköpfe is popular with freeriders (see below, Nockspitze Ski Tour). One long descent passes the Mutterer Alm ski resort and arrives at the bottom in Götzens. There is a snow park, Golden Roof Park, located near Karleitenlift.

As the mountains are at elevation and north-facing, the resort receives abundant snow. Some trails were used during the 1964 and 1976 Winter Olympics. Restaurants and hotels are located at the base and along the mountains, and a free shuttle bus runs between Innsbruck and the resort.

The Ampferstein is a classic that is readily accessible from Axamer Lizum. You start at the base and head south, gunning for the basin between the Widdersberg and the Ampferstein. After a while, it may become necessary to transition to a bootpack to gain the rest of the couloir.

As you can see from the images, there are a few different options; you don’t have to just follow the purple line on the app. The whole zone is north-facing, protected from the sun and, to some extent, the wind. As a result, you can often find pristine powder snow at the perfect 35° angle.

The Widdersberg is just next to the Ampferstein and is perfect for those seeking a more mellow adventure. If avalanche conditions are suspect, just head up the Widdersberg instead of its shadowy neighbor. It’s the same traverse into the basin as with Ampferstein. You can also access it with less climbing by riding the cable car to the top and traversing to the base of the South Ridge (see app).

The descent offers relaxed bowl skiing with plenty of southern exposure, so you can expect to find corn here on sunny spring days.

The Saile, or Nockspitze, is a classic in the area. For the rando chicks and dudes among you, head up from the valley for a full-value ascent of about 1500 meters (5,000 ft). For the rest of us mere mortals, take the Birgitzköpfl to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) and skin the remaining 400 m (1,300 ft) to the summit. Once there, you’ve got an array of north-facing couloirs or mellow and sunny south-facing meadows. The north-facing lines are steeper and make returning to the ski area much easier. That said, intermediates might prefer the alpine adventure of mellow south faces.

Innsbruck is around 30 minutes by car from Kalkkögel. With an international airport, public transport, and historical sites, it’s a great city to be based in to reach the mountains. If you’re looking to be in the heart of it all during winter, Axamer Lizum is the place to be. As the largest ski resort near Innsbruck, the resort offers more than 40 km (25 mi) of slopes, nine lifts, and numerous restaurants and lodges. For a quieter experience, check out one of the smaller villages, such as Grinzens.

Grinzens is a holiday village with a population of 1,400. Scenic and poised at the foot of the Kalkkögel mountains, the village is a stone’s throw from great hiking, rock climbing, and mountain biking opportunities. The Natterer See is a pristine natural lake for swimming in the summer. In winter, the village offers ice skating and curling, tobogganing at Kemater Alm, and plenty of winter hiking and cross-country skiing trails.

With a population of over 310,000, Innsbruck is an excellent destination for culture, nature, and proximity to mountain sports. It is the second-largest city in the Alps, after Grenoble, France, but arguably offers better mountain access. The city lies in a valley with steep mountains rising steeply around it; cable cars like the Nordkette and Patscherkofel provide quick access to the slopes for hiking, skiing, mountain biking, and paragliding.

Visitors can stroll through Old Town or pay a few Euros to climb the Town Tower. The Hofkirche church has 28 bronze statues, while the Cathedral of St. James shows off Baroque architecture. The Schloss fortress, a medieval fortress turned Renaissance castle for Archduke Ferdinand II’s wife, displays armor and artwork. Innsbruck hosted the Winter Olympics in 1964 and 1976 and the 1984 and ‘88 Winter Paralympics; the stadiums still host sports events.

Purchasing an Innsbruck Card is a worthwhile investment if you want to go to multiple museums, ride some cable cars, and have free transport on buses, trams, and bikes. The passes can be purchased for 24, 48, or 72 hours.

Innsbruck is a 30-minute drive from both Italy and Germany. Trains can arrive from Venice, Munich, Salzburg, and Zurich. The city also has a small but busy international airport and is a launching point for the famous Tyrolean ski resorts.

Explore Kalkkögel with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.