A Look at Meteorological Phenomena in the Mountains

PeakVisor represents a community that bows in awe of the majesty of mountains. And, if you’ve spent much time in the elevated world, you’ll understand that weather is one of the most spellbinding pieces of the mountain experience.

In the mountains, we are like Icarus. We fly close to the sun, and we mustn’t allow our wings to melt. Mountain weather tends toward extremes compared to our valley homes. Hot and sunny devolve into cold and rainy in an instant. Winds often reach hurricane force, enough to rip the roof off a house if there were any around. Snow falls by the meter. Cloud-to-ground lightning strikes can be a daily occurrence. Solar radiation is much higher at altitude.

Many meteorologists and climate scientists study mountain weather. Building weather models and conducting research requires a deep knowledge of hard sciences, such as thermodynamics, chemistry, and physics. It can be intimidating subject matter.

However, understanding the basics of mountain weather is an essential part of recreating in the mountains. We want a deeper understanding than just checking a forecast before going out. In this article, we’ll explain all the most important mountain weather phenomena in an easy-to-understand way.

Orographic Lift

Orographic lift is the granddaddy of mountain weather phenomena. When we think of “crazy mountain weather”—especially in the winter—much of that is due to orographic lift.

Orographic lift is when air rises as it encounters an obstacle that forces it upwards, namely, mountains. How does this affect weather? As air rises, it cools. As it cools, the air’s moisture condenses into clouds and, sometimes, precipitation.

Orographic lift can produce incredible amounts of precipitation. Just take Utah’s Wasatch Range, where Alta Ski Resort records over 12.5 meters (500 inches) of snow annually when the surrounding valley is a baking desert. Orographics are why you need to look at a mountain weather forecast before venturing into the backcountry. Just because there's a forecast for a couple of centimeters of snow in the valley doesn’t mean it will be the same on the high peaks.

Orographic lift also creates the wild cloud formations you see in the mountains. When air is forced to rise suddenly, it creates clouds we don’t see in the valleys. Lenticular clouds, which look like UFOs, are the most fascinating of these bizarre shapes.

The Rain Shadow Effect

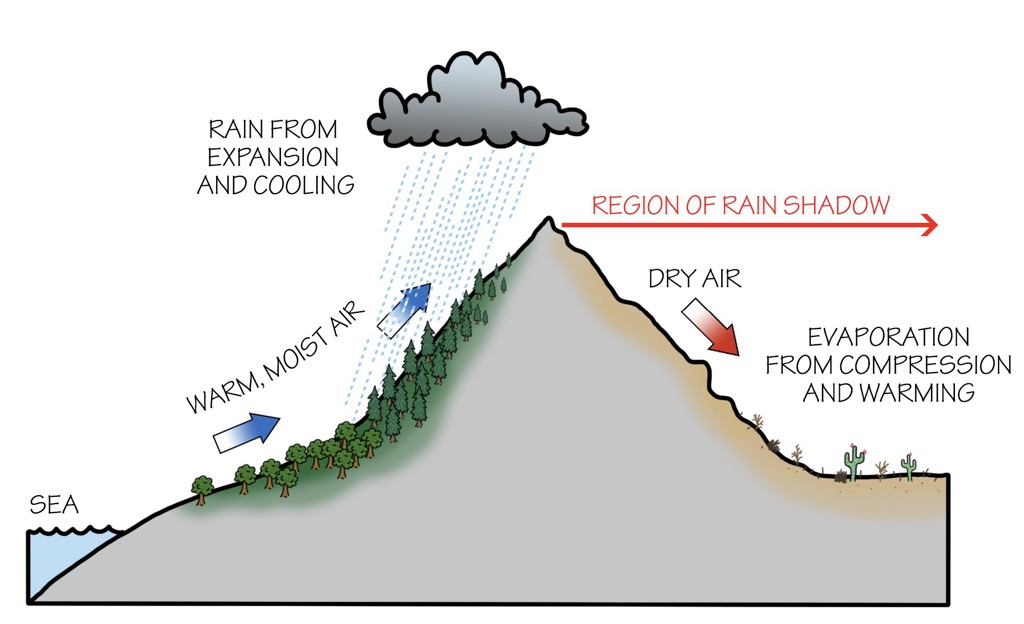

The most significant effect that mountains have on the Earth’s climate is what’s known as the Rain Shadow.

Rain shadows are dry regions that develop on the leeward side of a mountain range, away from the prevailing winds. PeakVisor's readership is mainly from the U.S. and Europe, where Western Continental North America is the most relatable example.

How is it possible that the immediate West Coast can be a temperate rainforest while the interior regions are largely desert?

Here, we take what we’ve learned about orographic lift and basically apply the opposite principle. As air rises over the windward side of a mountain range, it rises, expands, cools, and precipitates its moisture as precipitation.

The air is much drier as it descends on the leeward side of the range, having deposited its moisture. Moreover, as the air descends downslope, it compresses and warms, further drying out the landscape. In the winter, these winds are sometimes described as “snow-eaters,” and in summer or during dry seasons, they’ve contributed to devastating wildfires.

The coastal peaks from the Sierra Nevada in California to the Chugach in Alaska receive the initial orographic precipitation, while the valleys to the east are drier. The process can repeat itself along additional mountain ranges. This is how we have snowy mountains that are great for skiing amidst deserts throughout the Western U.S. and Canada.

These downslope winds have lots of names:

- Foehn winds occur in the European Alps. Föhn is also the word for “hairdryer” in German, as this wind is generally hot and dry—or at least much warmer than the air it displaces.

- Santa Ana Winds have been in the news recently with the 2025 fires in Los Angeles.

- Zonda Winds descend from the Andes in Argentina. They can reach speeds of 250 km/h (150 mph).

On a global scale, the Himalaya are the Earth’s best example of a rain shadow. The predominant wind direction is from the south, where the summer monsoon originates. Little of this moisture makes it past the Himalayan Crest, making Tibet and Western China a desert.

Thunderstorms

Mountains are notorious for summer thunderstorms. They may not be as awe-inspiring as the tornado-spawning supercell storms in the movie Twister, but mountains prodigiously produce thunderstorms.

Thunderstorms are a product of convection, when air moves from hotter areas to cooler areas. Mountain thunderstorms are almost always single-celled storms, sometimes called “popcorn” convection because of the shape of their cumulonimbus clouds. Thunderstorms only develop in the warmer months because warmer air carries the requisite moisture (and rises) to produce large cumulonimbus clouds. These clouds have lots of moving air and humidity, creating friction and electricity, which we experience as lightning.

There are a few reasons why thunderstorms tend to form over mountains. We’ll cover the two most important:

- The first reason mountains are so conducive to storms is Upslope Flow. Mountain sides heat up in the sun during the morning and early afternoon. The warm air begins to rise, eventually forming a cumulonimbus cloud and thunderstorms. Large temperature gradients between valleys and mountain slopes aid this process.

- We’ve already covered the second reason: Orographic Lift. Air rises as it hits the mountains. With enough instability and moisture in the atmosphere, it expands and cools. You still need convection, but orographic lift effectively aids the convective processes necessary to produce storms. Eventually, cumulonimbus clouds form.

In the grand scheme of things, these are weak systems that generally arise quickly and dissipate within an hour. There’s not enough warm air and moisture to sustain them for long. They don’t produce tornados, microbursts, or damaging winds and large hail (though they often create small hail stones).

Nevertheless, mountain thunderstorms are both incredible and dangerous. If you’re recreating in the mountains, it’s important to be aware of the possibility of afternoon thunderstorms. Getting caught in a thunderstorm in a valley is mostly inconvenient, but getting caught in the mountains is extremely dangerous.

Because there is little distance between the cumulonimbus clouds and the upper mountain slopes, cloud-to-ground lightning is frequent. Extraordinary lightning displays can be a daily occurrence in the mountains. Sudden torrential rain and hail can sometimes precipitate flash flooding. Once convection gets into gear, it can bring gusty winds and intense temperature changes as cold air rushes in to replace the warmer, rising air.

Summer storms happen in nearly every mountainous region of the globe, but there are three locations where it happens more often. These are places with a summer monsoon—that is, a climate featuring a surge of atmospheric moisture during summer:

- The Himalaya: The Himalaya is in direct line with the South Asian Monsoon, the world’s largest and most crucial monsoon event. The livelihoods of over a billion people rely on the annual monsoon. These are the biggest mountains in the world, and once convective forces get going, the range is off-limits. Climbing and trekking season is in the fall and spring to avoid winter and the summer monsoon.

- The Rockies: The North American Rockies, particularly in the Southwest U.S., are prone to monsoonal moisture surges. States like Colorado and New Mexico are notorious for afternoon thunderstorms like clockwork.

- The Andes: Monsoon season in the central Andes of Peru and Bolivia runs from November to March. Shifting wind patterns and atmospheric pressure draw warm, moist air from the Amazon Basin westward toward the mountains, causing rain to fall on the eastern slopes. During this period, more than 1,000 mm (400 inches) of rain can fall.

Snow in the Mountains

We all know that the mountains are notorious for snowfall. It’s not just because they’re colder; mountains really do catch storms and record whopping amounts of liquid precipitation during winter.

Quebec City is the snowiest city in North America, with about three meters (120 inches) of annual snowfall. The snowiest mountain is Mt. Baker, with about 16 meters (600 inches), though that’s only where we have proper equipment to accurately measure snowfall. There are surely pockets of mountains that receive far more snow, but where maintaining a weather station would be impossible.

In addition to being cold enough for more frequent snowfall, mountains receive storms in three ways:

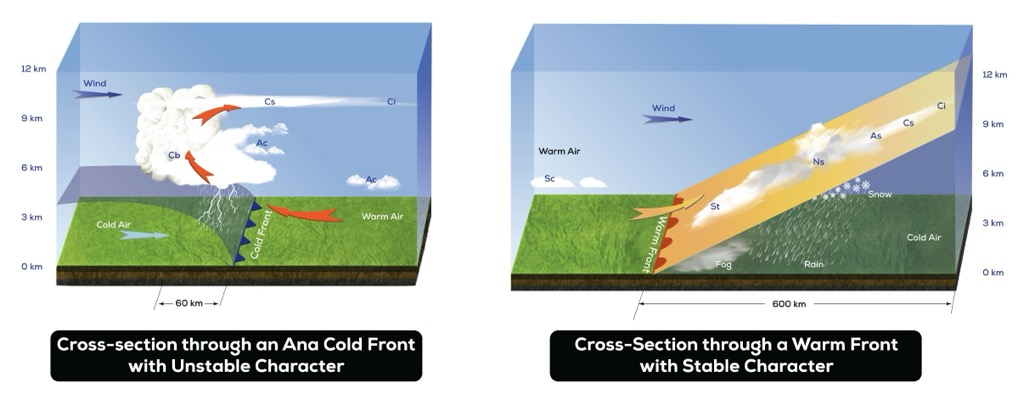

Frontal

Most people are familiar with frontal snowstorms because they comprise the vast majority of snow that falls throughout the valleys and flatlands where we build our cities and towns. When you hear about named winter storms each winter, you know these storms produce frontal precipitation. Fronts are more equal opportunity events, meaning both mountains and valleys get snow (though mountains will get more due to additional orographic lift).

A “front” refers to a mass of cold air that opposes a mass of warm air. Generally, the cold air rests near the surface while the warm air is pushed by cyclonic winds (the rotation of storms, like a hurricane), causing the warm air to rise. As we’ve learned, rising air expands, cools, and moisture condenses into clouds and snowfall. Fronts usually cover a large region with steady precipitation, i.e., the entire northeastern section of the U.S.

Orographic

As we’ve discussed, orographic lift is the granddaddy of mountain weather. It’s why there’s so much snow on top of the mountain and so little at the bottom. It’s why mountains get so much more snow—and precipitation generally—than the valleys.

One thing to note is that orographic precipitation can be highly localized. Not only is the snowfall limited to the higher elevations, but it's also limited to specific mountain ranges based on their geographic location and specific slopes based on their aspect.

Wind direction determines which ranges and slopes receive the most snow. Typically, orographics favor windward slopes, as well as the very top of leeward slopes, as snow is blown over the ridge.

Convective

We’ve already discussed convection in relation to mountain thunderstorms during the summer months. However, convection is also a driver of snowfall, particularly in the latter part of winter, as the sun gets stronger and temperature gradients between the peaks and valleys become more pronounced. Valleys and mountain slopes heat up during the day, causing air to rise. Pockets of cold air rush in to fill the void, intensifying the cycle. By the afternoon, enough air has risen to produce clouds and precipitation. If it’s cold enough, the precipitation falls as snow.

Convective snowfall is even more localized than orographic snowfall.

- On a temporal scale, convective snow showers are limited to the afternoon and early evening, particularly on days with bright and sunny mornings. They tend to be relatively brief compared to fronts and orographic events.

- On a spatial scale, convective snow showers are highly localized and random. It’s difficult to predict where a storm will pop up and how long it will last. These snow showers can be intense, delivering several centimeters (or inches) of snow in just a couple of hours.

Why Are Mountains So Windy?!

Wind in the mountains is nearly constant. Even when it’s not roaring at hurricane force, which it often is, there is almost always some sort of movement of air up here. It’s a defining feature of the mountain experience.

It depends on the range, but many mountains regularly experience winds well over the threshold for a hurricane, especially during winter.

No one factor causes the air to constantly be in flux over the mountains. It’s a combination of many different things.

- No Obstacles: Like the ocean and the plains, few obstacles exist in the mountains to stop the wind once you get above the treeline.

- Orographics: You guessed it. Orographics are at play again. Air can produce winds as it moves over the mountain and also as it descends. We’ve discussed these downsloping winds, i.e., foehn. Air compresses, warms, and accelerates downslope, producing some phenomenal gusts.

- Storm Forcing: These are the winds you encounter with a storm’s rotating energy. Hurricane gusts are an example of storm forcing, as the storm's rotation pulls air around with it.

- The Jet Stream: The jet stream is like a river of air moving at high speed in the Earth’s upper atmosphere, at about 9,000 meters (30,000 ft). Skiers and snowboarders love the jet stream, which dictates where the biggest low-pressure troughs will form. You need a favorable jet pattern to nail a good winter. Even though these currents exist at a high altitude, they can enhance wind speeds, especially near summits.

- Wind Tunnels: What do New York City and mountains have in common? They’re both wind tunnels. As winds are funneled through narrowings, whether buildings or mountains, the air accelerates to conserve momentum. Terrain features like canyons, mountain passes, and saddles often act as wind tunnels.

Inversions

Inversions occur when a layer of warmer air sits above cooler air near the surface. They often occur during calm, clear nights when the ground loses heat through radiation and warm air rises to the upper altitudes. In mountainous regions, cold air tends to sink and accumulate in valleys and basins due to its higher density, intensifying the inversion effect.

Inversions cause low clouds and fog. In the sea-of-clouds effect, valleys fill with fog while the peaks rise above in the sun. Inversions also often lead to poor air quality in valleys, as the stable, cooler layer traps pollutants and causes smog. Two places famous for their inversions (and smog) are Salt Lake City, U.S.A., and Chamonix, France.

Predicting Mountain Weather

Weather is notoriously difficult to predict. While we’ve made enormous strides in forecasting over the past few decades, anything accurate beyond five days remains elusive.

Why is Weather So Hard to Predict?

It’s the million-dollar question: why, when we live in a world with breathtaking technologies like artificial intelligence and net-positive nuclear fusion, do we still have so much trouble forecasting the weather?

The biggest challenge to our ability to predict weather is chaos theory. Its catchy name is sure to impress at cocktail parties…if you can explain it properly. It’s not relevant to just weather but to all future outcomes. Chaos theory is why nobody has ever been able to consistently and accurately predict the future.

Chaos theory is the science of future events determined by initial conditions yet unpredictable. Mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz summarized chaos as “when the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.”

Because of the cascading effect of errors in initial conditions, forecasts become progressively worse the farther you go into the future. It’s been said that forecasts get 10% less accurate the farther out you go, which makes them unreliable beyond a few days.

Where Do Errors Originate?

- Data Collection: We have developed incredible technology to monitor atmospheric conditions across the globe at all times. However, data collection is still imperfect, and these imperfections are amplified when predicting future events.

- Dozens of Variables: The more variables you have in an equation, the more complex the equation will be. The atmosphere is host to numerous variables, such as temperature, humidity, pressure, and solar radiation.

- Computer Models: We’ve developed many complex weather models that run simulations based on data about the current state of the atmosphere. Nevertheless—like data collection—these models are imperfect, and imperfections are amplified when predicting the future.

- Unpredictable Events: Some events are simply unpredictable with today’s technologies yet have an outsized impact on our weather systems. These include volcanic eruptions and solar activity.

The Micro-scale of Mountains

Not only is weather difficult to forecast generally, it’s even harder to forecast in the mountains! That’s because most mountain weather is the product of highly localized variables. The subtlest differences in aspect and wind direction can make an outsized impact on the weather. It’s impossible to gather all the necessary data, nor do we have weather models with enough resolution to highlight such specific terrain.

Best Mountain Weather Forecasting Sites

*PeakVisor did not accept money from any of these outlets. They’re just the tools I use for my own recreation in the mountains.

- OpenSnow: OpenSnow (site/app) was originally founded to provide skiers and snowboarders with forecasts about where to find the best snow conditions. The service uses a blend of weather models, not just one, which makes its forecasts more accurate. It offers enlightening “daily snow” written forecasts for most ski regions worldwide. It’s evolved into a summer weather app as well.

- WePowder: WePowder is for skiers and snowboarders during the winter months. The best thing about this site is the excellent written forecasts tailored for skiers. Like OpenSnow, they try to direct you to the powder, but only for the Alps. There’s also a decent community on the site’s forum. They’ve got their own weather model, but it’s not as good as the ECMWF or GFS models, which are backed by lots of resources.

- Tropical Tidbits: Tropical Tidbits is where to go if you want to really nerd out on weather forecasting and interpret the data for yourself. You can run the major weather models and play around with the various parameters. Unless you’re a pro, it’s going to be hard to garner an accurate forecast because most forecasts average several different models. But still, it’s seriously fun to play around with, and you can gain insight into the variation between different models.

Long-Term Forecasts

Clickbait weather services like Accuweather offer daily forecasts stretching to 40 days, but this is nonsense; you’re better off with a crystal ball.

However, there are some ways to approximate weather in the medium-to-long term. Meteorologists have developed models to account for variables like ocean temperatures and cyclical variations. These models then forecast the likelihood of general trends, such as whether temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric pressure will be above or below average.

The ECMWF offers medium-to-long-term forecasts that are free to the public. They’re an excellent tool for anyone looking to speculate on future weather, such as whether ski conditions might be good. I wouldn’t put too much stock into these forecasts, but they’re fun to play around with.

Making Your Own Weather Predictions

Building your own forecasts from scratch is hard. However, you can consider certain factors to gain additional insight into the local weather. With time and observation, you can use your local insight to re-fit low-resolution forecasts from the major weather models.

- Wind direction: Wind direction is one of the best ways to adjust a mountain forecast. It takes some familiarity with the terrain. If the wind is out of the northwest, you may not want to hike in a narrow, northwest-facing terrain feature, as that could act as a wind tunnel, even if the wind is not strong elsewhere. Often, leeward slopes can offer protection from wind.

If you’re passionate about winter sports, wind is also integral in forecasting snow. Every mountain is favored by certain wind directions and not favored by others. The differences can be even more localized, to slopes of different aspects on the same mountain.

Here’s an example. My home mountain, La Grave, is in the Western Alps in France. Many snowstorms in the Alps come from the northwest. Every time, like clockwork, the weather forecasts show lots of snow for La Grave. That’s because the mountain faces north, and it’s located on the western side of the Alps. But every time, like clockwork, we get less snow than forecast because the Grandes Rousses Massif is directly in front of us to the northwest. They get the brunt of the orographic advantage; we get much less snow and lots of wind.

Mountain forecasts across the globe are full of discrepancies like this. The big weather models aren’t meant for such abrupt terrain features and don’t read the fine print.

Biggest Mountain Weather Risks

There is a virtually limitless list of things that will kill you in the mountains, and bad weather ranks right up there with the most likely. A sizable percentage of all mountain deaths are ultimately weather-related. Here’s what you need to watch out for.

Exposure (Hypothermia / Hyperthermia / Frostbite)

To "die of exposure" refers to death by the elements, namely extreme cold, heat, or dehydration. It occurs when the human body is unable to maintain its core temperature or essential functions due to the harsh environment.

Mountains are known for their cold temperatures, so hypothermia and frostbite are more common. Many high-altitude mountaineers die of hypothermia. In fact, to make it through a few expeditions with all your fingers and toes surviving frostbite would be a miracle.

For the mere mortals among us—hikers, skiers, and other ordinary backcountry enthusiasts—hypothermia usually occurs when the weather suddenly changes for the worse or when an accident prevents movement. Wind can exacerbate frostbite, particularly on the face.

Hyperthermia is less likely in the mountains because of cooler temps than in the valleys, but strenuous activities can add to the risk. Be sure to consume plenty of water and electrolytes.

Heavy Snow / Avalanches

Avalanches are masses of snow, ice, and rock moving down a mountainside, powered by gravitational force. While these are the common denominators of avalanches, nearly all their other characteristics vary. They can be tiny or massive, slow or fast, high or low elevation, predictable or seemingly random.

Each year, avalanches claim the lives of approximately 150 backcountry enthusiasts worldwide, making them the most frequent cause of death amongst ski tourers and freeriders (63% of fatalities).

Avalanches typically occur during or directly after fresh snow. However, depending on weather conditions, they can also occur long after a storm.

Many different factors can cause avalanches. Cold, dry weather patterns can create a temperature gradient within the snowpack, forming faceted snow crystals. Large avalanches can then run off these crystals, which offer less friction than a well-bonded snowpack. Wind can transport snow and create avalanche danger without any fresh snow actually falling from the sky. Warming can trigger wet slides.

Check out our PeakVisor article to learn more about avalanches and avalanche safety.

Lightning Strikes

Lightning strikes are incredibly rare. Colloquially, we say, “That’s like getting struck by lightning," referring to someone who has been very unlucky.

However, getting struck by lightning is a very real possibility in the mountains. About 24,000 people are killed by lightning each year, and about 25% of those are outdoor recreationists (outdoor workers account for the highest percentage, at 30%). Though lightning merits its deadly reputation, about 90% of the 240,000 people struck each year ultimately survive.

Storms can seemingly spring out of nowhere in the mountains. Getting caught above the treeline is likely the most dangerous; here, you’re the tallest object, and you will likely have some amount of metal gear. If you’re caught, don’t seek shelter under a tree. Instead, crouch low, don’t touch the ground, and spread out so other group members can assist if one person is struck. Unlike heart attacks, cardiac arrest by lightning is often reversible with CPR.

Sunburn

Not only does the Earth’s atmosphere produce weather, but it also contains Ozone and other molecules that help block the sun’s UV rays.

Up in the mountains, there’s less atmosphere between you and Mr. Sun, and therefore more UV radiation. Often, snow and ice reflect the sun and intensify the rays.

Recreationists should always wear sunscreen and try to cover with a physical barrier when possible. It’s not just about skin cancer; your face will look like it’s made of leather if you’ve spent too many decades out in the high alpine sun. Believe me, I’ve seen it many times.

The PeakVisor App

Here at PeakVisor, we love mountains. We also love information. That’s why we write articles like this one. We don’t receive any ad revenue or sponsorships. Our source of revenue is our 3D mapping and peak identification app for iPhone!

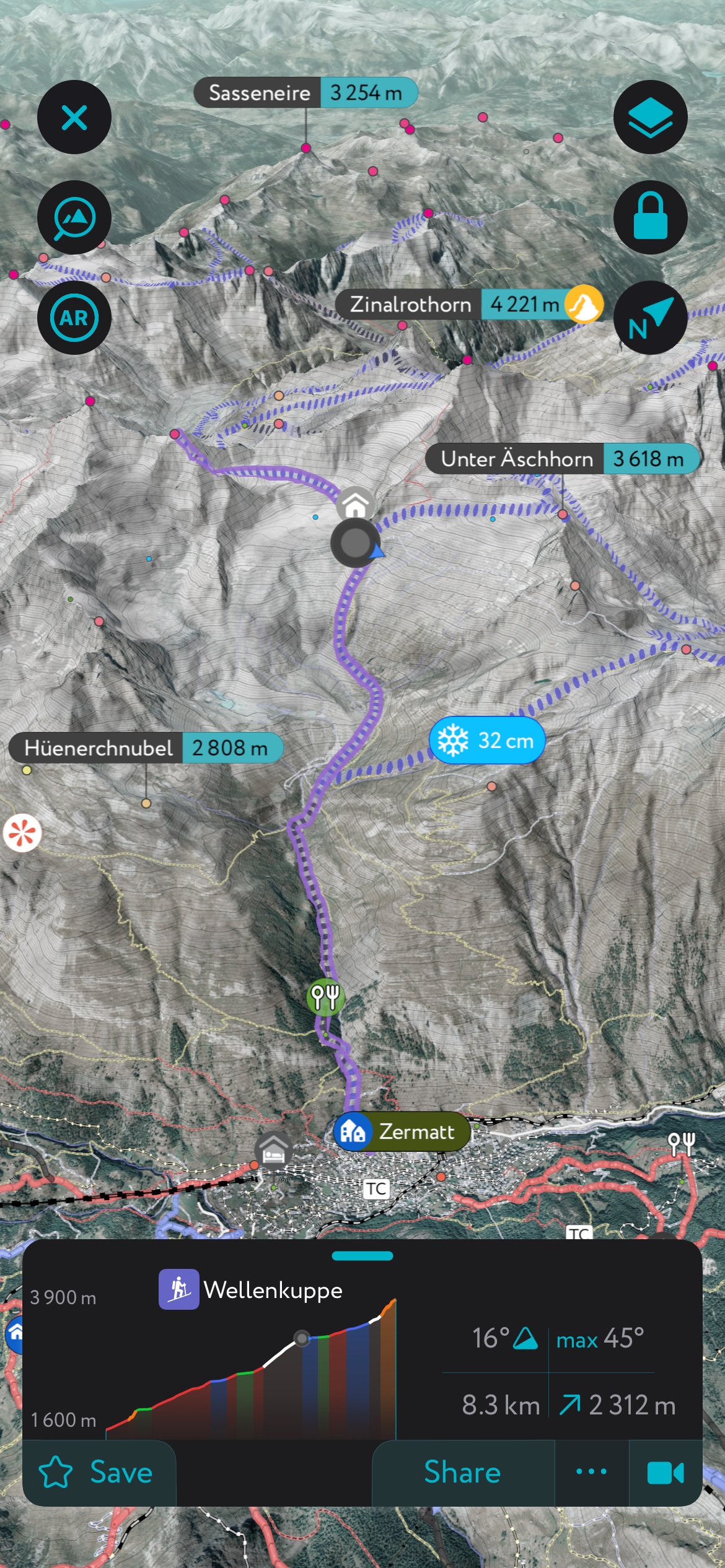

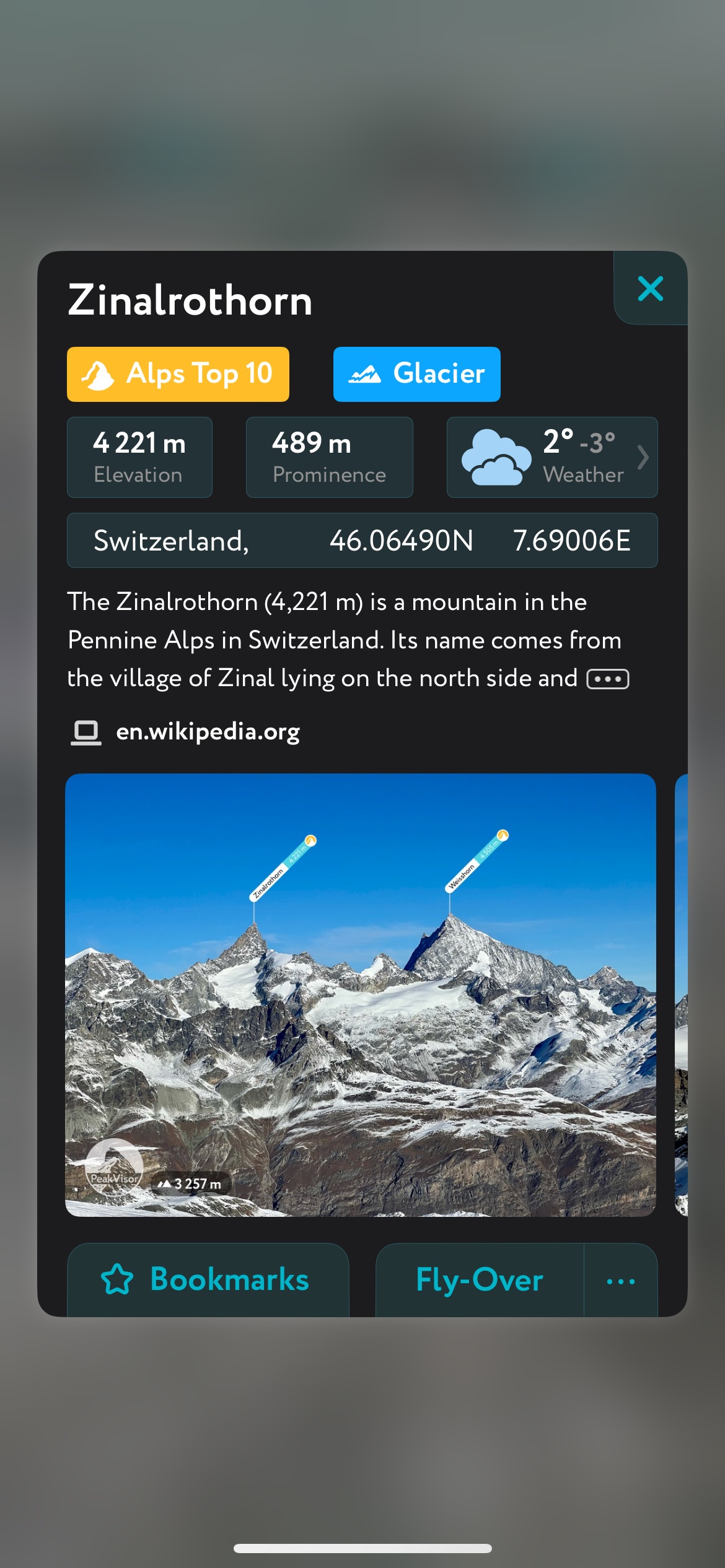

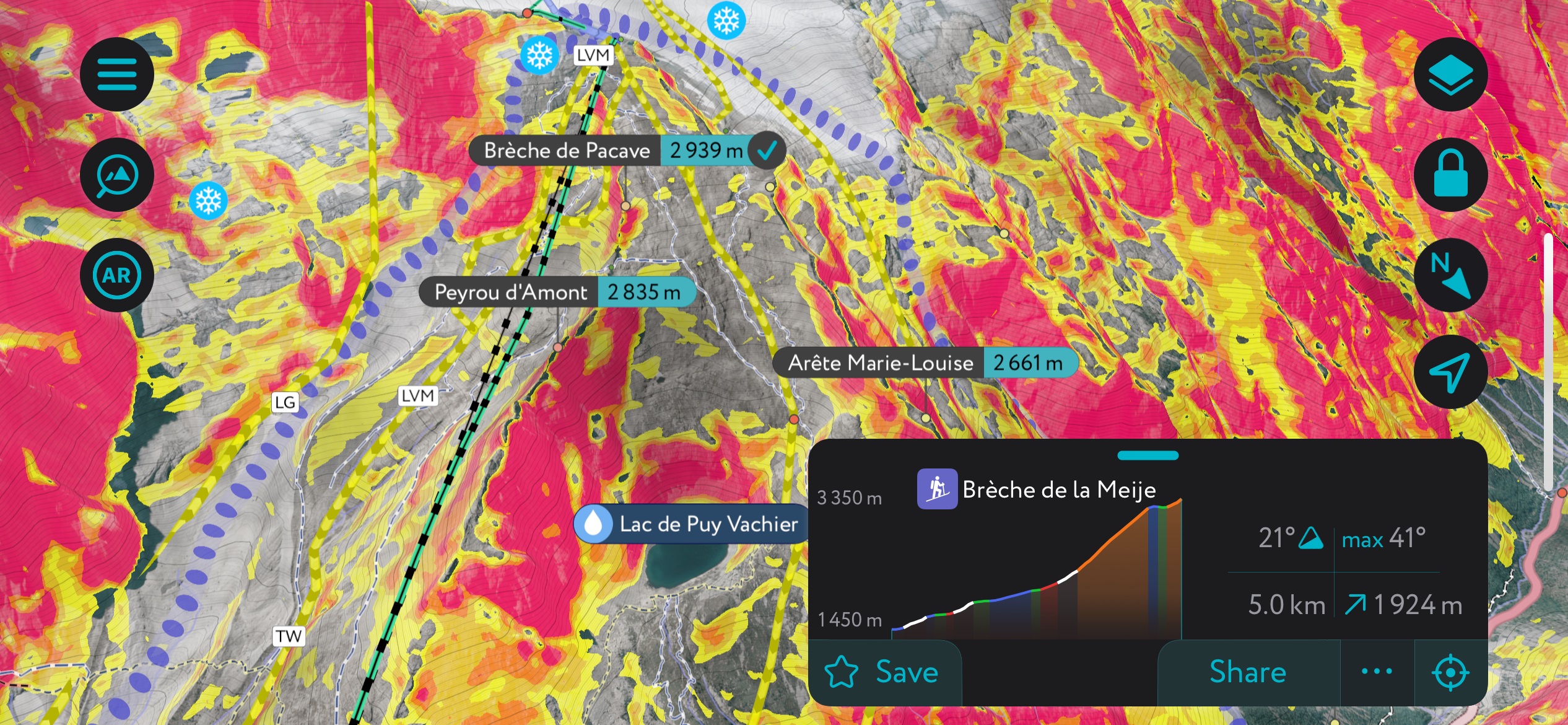

PeakVisor has been a leader in the augmented reality 3D mapping space for the better part of a decade. We’re the product of nearly a decade of effort from a small software studio smack dab in the middle of the Alps. Our detailed 3D maps are the perfect tool for hiking, ski touring, biking, alpinism, and more.

PeakVisor Features

In addition to the visually stunning maps, PeakVisor's advantage is its variety of tools for the backcountry:

- Thousands of hiking trails and ski touring routes throughout the Alps and beyond.

- Slope angles to help evaluate avalanche terrain.

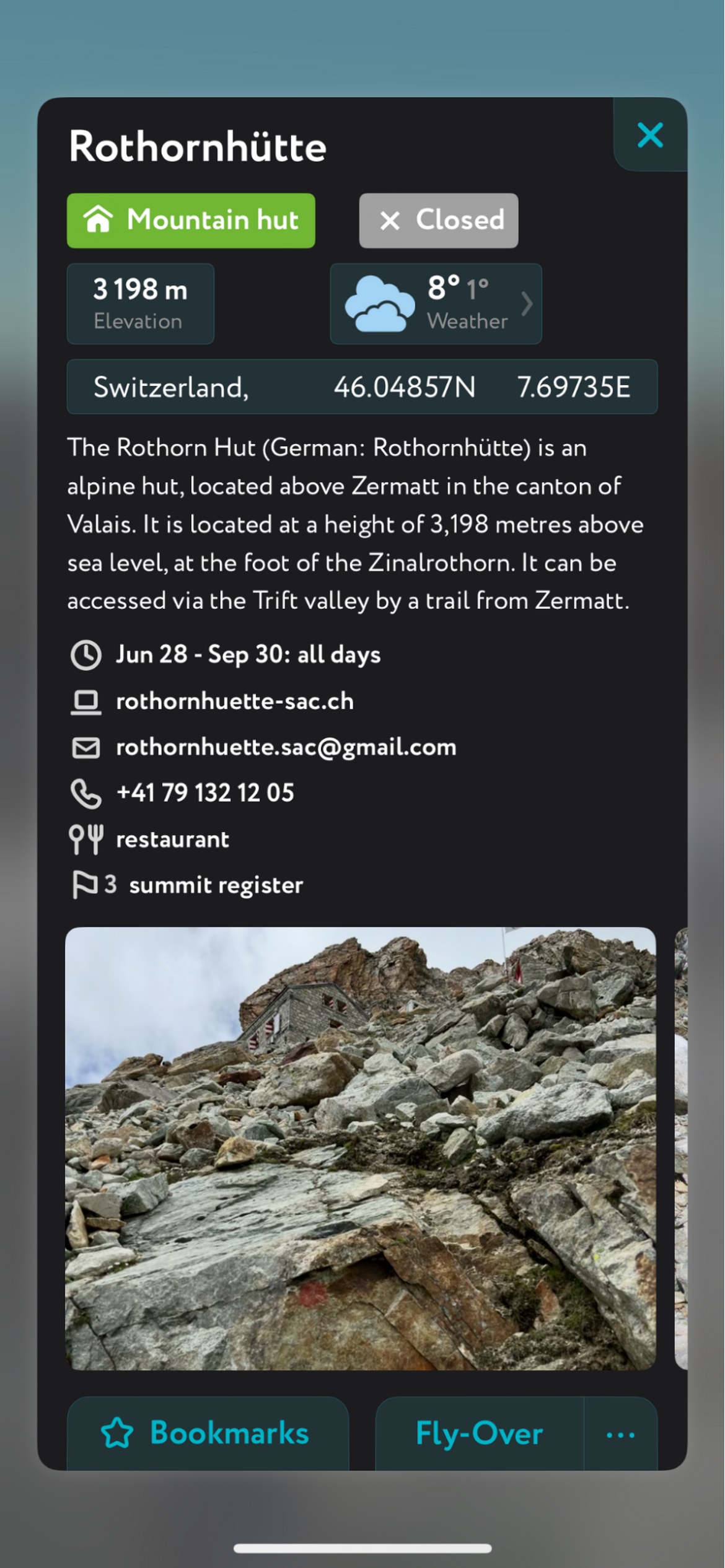

- Mountain hut schedules and contact info save the time and hassle of digging them up separately.

- The route finder feature generates a route for any location on the map. You can tap on the route to view it in more detail, including max and average slope angle, length, and elevation gain.

- Up-to-date snow depth readings from weather stations around the world.

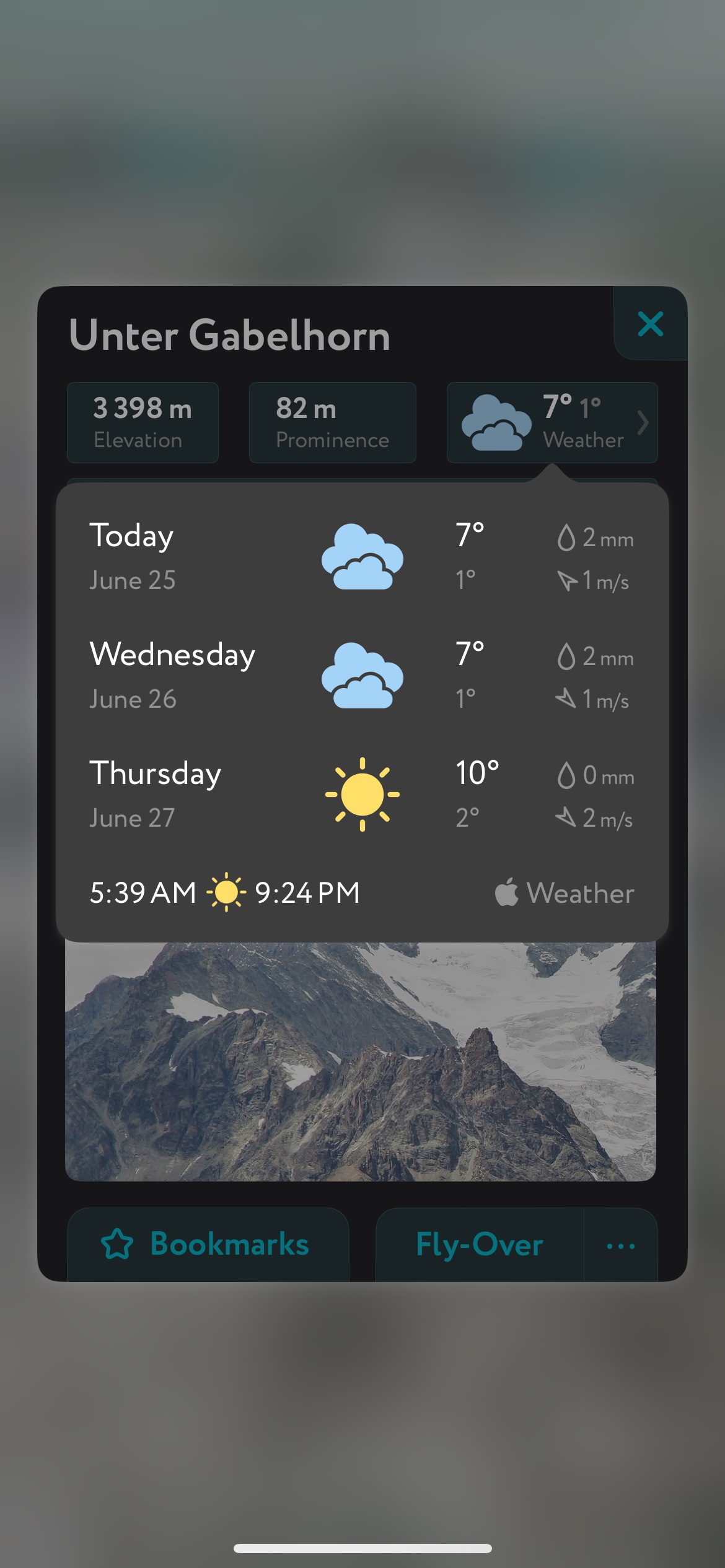

- A point weather forecast for any tap-able location on the map, tailored to the exact GPS location to account for local variations in elevation, aspect, etc., that are standard in the mountains.

- You can use our Hiking Map and Ski Touring Map on your desktop to create GPX files for routes to follow later in the app.