Utah Has a Trademark on the Name. But the Earth Is a Big Place, and There’s More to the Story

For the skiers among us, snow is more than one of Earth’s most delightful phenomena. It’s our raison d’être, the thing that gets us out of bed each morning. Knowing that there will be another powder day, someday in the future (yes, even in the age of climate change).

“One can never be bored by powder skiing because it is a special gift of the relationship between earth and sky. It only comes in sufficient amounts in particular places, at certain times on this earth; it lasts only a limited amount of time before sun and wind changes it. People devote their whole lives to it for the pleasure of being so purely played by gravity and snow.”

Dolores LaChapelle

But here’s the rub. Not all snow is created equal. Generally speaking, the best snow is the freshly fallen sort, with no tracks from previous skiers or riders. But there are a few places on Earth where conditions align to create something even more perfect. It’s that snow that feels like little more than air. You ski within this magical substance, not on top of it. It’s what Dolores LaChapelle is speaking of when she says, “being so purely played by gravity and snow.”

The Stellar Dendrite

Of all the different types of snow, none is more agreeable to skiers than the stellar dendrite. These crystals have a large, well-defined lattice structure and pile up on the ground with lots of air between them, creating super light powder. It’s the type of snow that flies up over your shoulder and into your face. It leaves a trail of crystals behind every skier like a comet, e.g., “cold smoke.” And, you can pick it up with your hand and blow it away, hence the nickname “blower pow.”

Snow-water equivalent (SWE) is an important metric to understand. It’s the ratio of liquid water in a certain amount of snowfall. When conditions are just right, just 1 cm of liquid water can add up to 25 cm of snowfall. So, if you were to melt 25 cm of snow, you’d get just 1 cm of water, meaning the snow has 4% water content. That is most certainly blower pow.

Stellar dendrites require two main conditions to form. Firstly, temperatures should be in the range of -10 and -15℃ (15 and 5℉). That’s the sweet spot where the air is cold but can still hold enough moisture to form an extensive lattice structure. If it’s too warm, the snow will have too much water and therefore be too dense to behave like blower powder. On the other hand, if it’s too cold, the air will lack enough moisture to form a good lattice structure. Instead, you get both fewer flakes and smaller crystals.

Secondly—and perhaps even more importantly—there must be little to no wind. Wind knocks the fragile crystals into each other, breaking them apart. You might have plenty of moisture and nice cold temps, which is already a blessing in and of itself. Yet, having wind in the equation will knock those snow rations down to 12 to 15:1.

If you’ve spent much time in the mountains, you’ll understand that these conditions are hard to come by. They’re special. There’s no place that just averages blower pow. Passionate skiers will already know about Utah or Japan’s legendary snow. But understanding why it’s so great will hopefully help you pick the best ski days and ski locales in the future.

Salt Lake City, The Greatest Snow on Earth®

In 1960, the state of Utah, USA, trademarked the slogan “The Greatest Snow on Earth” to boost tourism to several newly minted ski resorts. Now, the U.S. is chock-full of false marketing claims coming at you from every direction. But there’s actually quite a bit of truth to the claim of having the “best” snow, at least in two specific canyons: Little Cottonwood and Big Cottonwood.

Little and Big Cottonwood Canyons (LCC and BCC) are essentially unique amongst Earth’s mountains. There’s nowhere else that receives quite as much snow while consistently maintaining that dry snow quality.

Sure, there are places with drier snow; Colorado is even further from the Pacific Ocean and experiences drier snowfall overall, particularly in areas like Steamboat and Telluride. But the snow totals in the Cottonwoods put Colorado resorts to absolute shame. In the 2022-23 season, Alta Ski Resort received an astonishing 22.94 meters of snow (903 inches), while Telluride received 6.78 meters (267 inches)—and it was still one of Telluride’s top 10 seasons.

In fact, Alta receives an average of over 12 meters of snow annually (> 500 inches), as do the other resorts of The Cottonwoods: Snowbird, Solitude, and Brighton. These two canyons run west to east, the same direction as the predominant storm track in the Intermountain Western USA.

After the Sierra Nevada, the Cottonwoods are the first prominent range in the way of storms. These storms push air up over 2100 meters of prominence, causing moisture to condense and fall as snow. This process is known as orographic lift, and the Cottonwoods are very efficient at it. These canyons' general west → east direction means excellent orographics from southwest, west, and northwest winds.

But even that is not the whole story. Storms spin counterclockwise and therefore often arrive with an initial period of southwest winds, which tend to bring denser snow (not the “greatest snow on Earth”). Many of these storms finish with northwesterly winds from the “backside” of the storm. Meanwhile, the Great Salt Lake provides a bit of extra moisture that gets picked up by northwest winds and deposited in the Cottonwoods, specifically Little Cottonwood. It’s this last shot of snow that often reaches the hallowed levels of less than 5% water content (20:1).

Skiing powder is significantly less enjoyable if you sink to the bottom and scrape the hard snow from before. Yet, the magic of the Cottonwoods is that they provide enough snow and the right layering to give your skis that “bottomless” feeling. Skiers call storms where light snow falls on denser snow “right side up.” Not only is the skiing better, but it’s also safer from an avalanche perspective; the denser snow is able to support the lighter snow.

In 2022-23, Alta claims to have recorded 44 days with at least 30 cm (12 inches) of fresh snow. Combine a supportive base with blower pow on top and you have the perfect recipe for powder skiing.

Salt Lake isn’t my favorite place in the world to ski; it’s crowded, getting to and from the mountains is notoriously difficult, and there’s not too much charm at the resorts or in the big city, to name a few reasons (even though it gets less than half as much snow, Telluride is, in my opinion, a superior ski area). But no matter what you think of the overall ski experience, these guys have unbelievable powder days…respect.

“Japan-uary”

Japan is a mystery to just about nobody in the ski industry these days. You could even say it’s been overhyped. You may or may not have an enjoyable ski experience here, depending on what you’re looking for. But there’s no denying that the weather phenomenon that produces Japan’s snowfall is fascinating. Let’s dive into how it works.

Japan is very far south, as far as skiing countries go, with resorts generally between 35 and 43°N latitude. The famous Niseko Ski Resort sits at 42°N and about 100 meters above sea level—about the same as Rome or New York— yet it experiences some of the most legendary snowfalls on the planet.

Unlike any other locales in this article, Japan is in a snowbelt caused by a relatively uncommon phenomenon called ocean-effect snow (the same as lake-effect snow, but with saline water). It’s a rare occurrence because it requires a vast body of relatively warm water along with cold winds. The temperature gradient, or difference, between the water and air must be very high, with the air being at least 13℃ (20℉) colder. There’s plenty of ocean-effect rain on our planet but little ocean-effect snow.

The warm body of water is the Sea of Japan. And the winds originate from the plains of Siberia, one of the planet’s largest arctic landmasses. Like most Arctic landmasses, Siberia is largely a desert characterized by dry, cold air and persistent high pressure during winter. The relative low pressure of the Pacific Ocean creates a pressure gradient, with air flowing toward the lower pressure, sending consistent winds southward to Japan.

Next, the winds gather moisture from the Sea of Japan. The final piece of the puzzle is orographic lift. The air rises as these freshly moisture-laden winds bump up against Japan’s mountains. As it rises, it cools, and the moisture condenses into snowfall.

The product of this intricate dance of air and water is the planet’s best snow conditions, specifically for about six to eight weeks in January and February. Now that we understand the physics of what’s going on in the sky, here’s what’s happening on the slopes: endless snow showers that steadily drop 10, 15, 20 cm of snow each day, and the Siberian air mass is still dry enough to produce that desirable fluffy snow. Moreover, nearly all the skiing is below treeline, which means less damage from the wind.

Big dumps are not as common as you might think, but the consistency of the snowfall sets up the perfect conditions for powder skiing: plenty of light, dry snow on top with a soft base down below. Most days, there’s no such thing as a bottom. Niseko Resort claims 14 meters of snow on average, which is already among the world’s highest. But when you consider that the vast majority of this snow falls in 10 weeks, now that is seriously impressive.

But be warned. As soon as the Siberian winds run out of steam—usually at around the end of February or early March—the season is effectively over. And don’t bother trying to pick your way through bamboo forests unless there is ample snow coverage, usually not until after Christmas. The season is short here.

Looking to bask in the sun in a lawn chair? It’s not happening in Japan. Sunny days are few and far between. Want to discover the steep and deep? Also difficult to find, as the mountains here are rather benign. Japan is not everyone’s cup of tea, but for a few weeks each winter, it’s home to some of the greatest snow on Earth.

Alaska, Heroic Steeps

Utah and Japan sure get a lot of snow, but they aren’t the snowiest regions in the world. That title belongs to the Pacific Northwest, extending from the Cascades of Washington State through the Coast Range of BC and all the way up to the Chugach Range of Alaska.

Moisture-laden low-pressure systems roll in off the Pacific Ocean and, without further ado, collide with the mountains. The moist air rises, and voila, moisture condenses into snowflakes. While they are legendary for snow quantity, these coastal mountains are less reputable for their snow quality. Nicknames for this dense, maritime mixture include Sierra cement and Cascade concrete. With so much moisture and mild air coming off the great expanse of the Pacific—not to mention wind that will rip the roof off of a building—the ingredients just aren’t there for dendrites of the stellar variety.

The Chugach Range marks one of the northernmost groups of mountains along the American Cordillera, which stretches from southern Patagonia to the Aleutians of Alaska. It’s likely one of the snowiest places on Earth. The SNOTEL weather station at 530 meters (1,700 ft) on Thompson’s Pass measures some 14 meters of snow a year. Seeing as the range’s highest elevation is over 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) with an average of over 1,300 meters (4,000 ft), we can surmise that even more massive amounts of snow plaster the highest peaks.

The Chugach is still the epitome of a maritime range; its glaciers flow into the tidewaters of the Pacific Ocean in spectacular fashion. But at approximately 61°N, the range is also subject to bitterly cold, dry air from the Arctic expanse to its north. Snowfall comes in wet from the Pacific, gels to even the steepest faces, and then experiences a “powder-ification” of sorts, as dry arctic air sucks the moisture out of the top layers of the snowpack.

The resulting ski surface is reputed to be among the best—and easiest—in the world to shred. Like the Cottonwood Canyons, the cold, fluffy snow on top and slightly denser snow below is the perfect medium for skiers to paint their tracks down the mountain. As a result, the Chugach is legendary for its steep skiing. The powder might not be as pristine as in Utah, but it’s darn close, and the maritime snowpack reduces avalanche danger, making it possible to light up the steepest slopes just days after a storm. Pros come here to test the limits of what’s possible on skis, while mere mortals come here to, for a brief moment, feel as if they are pros.

Of course, all this snowfall means relatively few days of clear weather. And because there are no ski resorts, or any infrastructure for that matter, skiing is accessed mainly via helicopter or snowmobile. Cost becomes a significant issue.

For me, this is all secondhand reporting. PeakVisor hasn’t yet offered to sponsor my $15K heli-ski trip to Alaska, but even if they did, it requires a bit of luck to get clear days and stable avalanche conditions. One thing is sure, though. Even if the Chugach isn’t home to the driest snow, it’s undoubtedly the best on Earth for steep skiing when it’s on.

Glacier Skiing in Europe

Skiing in Europe, particularly the Alps, is not known for powder snow conditions like Utah or Japan. But hear me out.

The Alps are high in both latitude and altitude and are subject to maritime and polar influences, not to mention the Gulf Stream, which feeds warm air from the tropics up the Atlantic. During mid-winter, much of the precipitation is “frontal” in nature, which means that large low-pressure systems spin off the Atlantic and bring precipitation (with additional orographic enhancement by forcing air over the mountains). These fronts have a lot of wind and most of the skiing in Europe is above treeline. Therefore, people usually associate Europe with dense, windblown snow.

However, come late February, March, and even April, the weather tends to change, and the nature of precipitation often becomes more convective. Convective snow showers are like the snow version of thunderstorms. We know that warm air rises and cool air sinks. In this case, the air heats up in the lower valleys and begins to rise, a process accelerated by cooler air from the high mountains sinking down to replace it. If the rising air has enough moisture, you’ll see condensation in the form of snow. Europe is great for convective snow showers because the elevation difference between the high peaks and valleys is extreme, almost Himalayan in scale in some places.

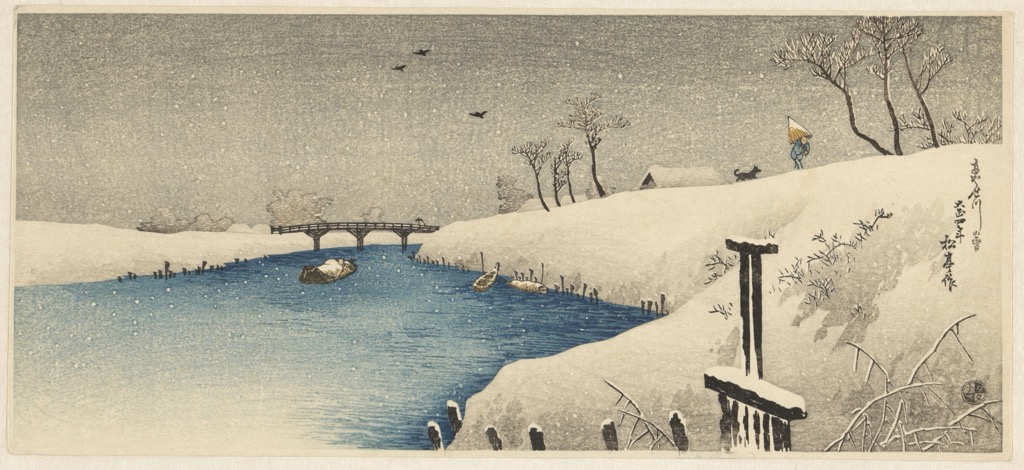

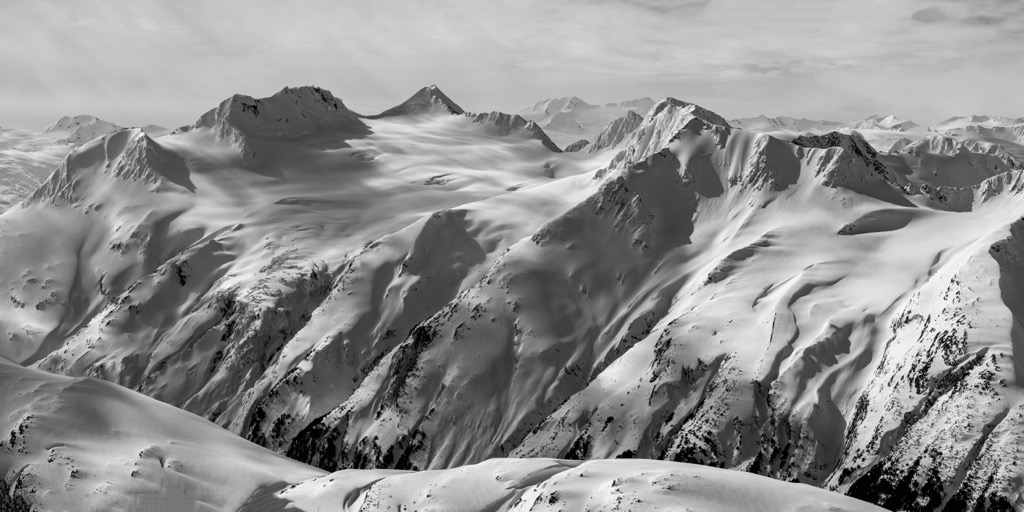

Some of the finest powder snow lurks on Europe’s high glaciers in spring. Photos: Sergei Poljak

Like thunderstorms, convective snow showers generally fire up in the afternoon and evening and can be quite intense. The upper mountain temperatures are often in that perfect range, between -10 and -15℃ (15 and 5℉), and the updrafts associated with connective showers in the Alps are nowhere near the winds seen with frontal passages. That makes conditions ideal for the formation of stellar dendrites, and I, for one, have seen some impressive “goose feathers” associated with this type of precipitation.

The Alps are really the only place in the world with easy lift access to glacier skiing. Sure, all the snow seems to get blown off the top of the mountain during mid-winter, but the glaciers are where these showers deposit the most snow in spring.

Moreover, convective snow tapers off in the evening, leaving cold, dry night air that further dries out the new coating of snow. The thick ice beneath the snowpack keeps everything refrigerated from the inside out, preventing the formation of a crust in the spring sun. Glaciers provide giant open bowls to make turns without having to worry about obstacles (save the occasional crevasse or two).

Many experienced skiers say that the best snow is found high up in the Alps. Although this phenomenon seems to be becoming less common due to climate change, I’d have to agree. I’ve skied all over the world, including many seasons in Colorado, but in my ten full ski seasons, the lightest, driest, and most perfect powder skiing has been on Europe’s glaciers.

Conclusion

There’s no such thing as bad snow—only bad skiers. If snow is falling from the sky, I’m inclined to sit by the window and watch it, contemplating the flakes as they dance down from the heavens. Sometimes, those flakes are stellar dendrites…usually, they are not.

I wrote this article for skiers who might be interested in how our planet manages to create magic in the form of ultra-light snow. But, ultimately, the greatest snow is the snow you’re skiing at any given moment. Spend enough time out skiing in any region of the world, and it won’t take long to stumble upon a magical moment in the snow.