Introduction

Climbing and skiing Mont Blanc in a day almost happened by mistake. How could that be possible, you ask? Did I slip on a banana peel and end up at the top of the tallest mountain in western Europe? Here’s the story.

It was mid-May, and the ski season had long since concluded. So long, in fact, that those pictures from February vacation are now collecting dust on the kitchen fridge or buried deep in the hard drive.

Even the ski touring season had wrapped up, with all but the highest altitude refuges closing their doors and hunkering down ‘til summer.

But Mont Blanc didn’t become “blanc” for nothing. After a week of rain showers in the valleys and snowstorms up high, conditions were ripe for the taking.

Originally, I planned a high-altitude ski tour to the legendary—in the ski-mountaineering community—Castore (4,228 m / 13,871 ft), one of the 4,000-meter peaks in the Montarosa Massif. Its fame is derived from the Trofeo Mezzalama, a ski alpinism race traversing the summit.

However, weather and avalanche conditions shifted the plans to heliskiing, which is quite popular in the Aosta Valley. At the last minute, plans changed again to drop at Pitons des Italiens (4,024 m / 13,202 ft), on the Mont Blanc Massif instead of the Montarosa Massif.

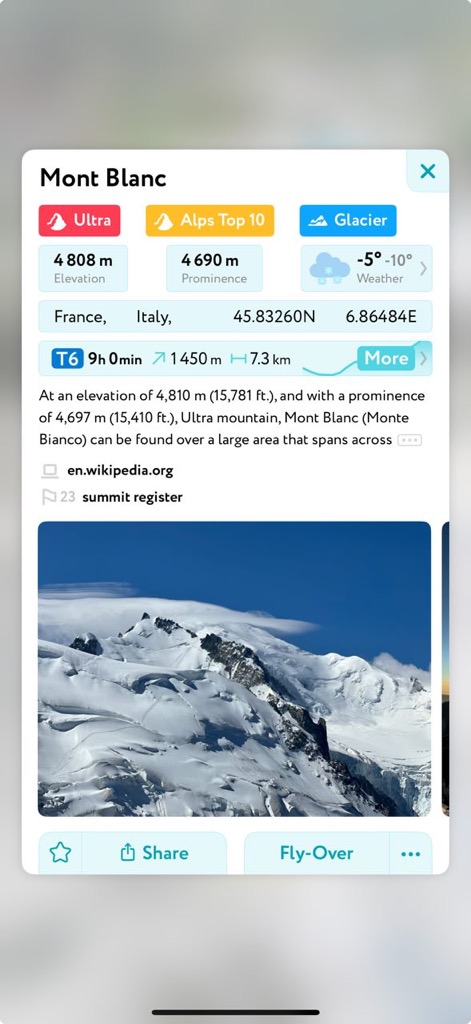

That leaves just 800 meters of elevation gain to reach the top of the Alps on Mont Blanc’s 4,808-meter (15,774-foot) summit. From there, it’s a 2,500-meter ski descent to the Aiguille du Midi mid-station.

I’ve hesitated climbing Mont Blanc for years because the normal routes require booking mountain huts so far in advance that you can’t be sure of the snow and weather conditions. The route is almost always crowded. For these and other reasons, Mont Blanc is, by far, the deadliest mountain in the world. Around 8,000 people have died on its slopes. And if you do die on the Mont Blanc, your last night of sleep will probably be a bad one; the refuges are notoriously loud and smelly. Good luck catching some shut-eye.

Since mountaintop views, snow conditions, and a generally pleasant (or at least tolerable) environment are important to me, I wasn’t willing to risk it.

The Ascent

The mountains had been socked in clouds for the last week as a large group of us waited at the heliport in Cormayeur. The clouds were stubborn, slowly retreating from high peaks as the sun warmed the atmosphere. The helicopter arrived at 10 a.m., an hour after our planned cancellation time of 9. Nevertheless, we proceeded.

The panoramic heliflight brought us over Val Veny to the Pitons des Italiens. We were above the clouds. The endless sky was a deep azure blue, cleansed by a week of storms. Craggy mountains sprouted in all directions, insulated by a cloak of snow-covered glaciers.

The route from here simply follows the principal ridge up to the summit of Mont Blanc. It had already been tracked by the time we arrived. I imagine it’s quite rare that you get to be the one putting in the track here…

The first part of the route from Pitons des Italiens reaches the Dôme du Goûter, the Col du Dôme, where the Italian and French routes meet, and finally to Refuge Vallot (4,322 m / 14,180 ft), which is more like a bivouac.

Next, the route reaches a steep section where climbers rope up, strap on their crampons, and proceed with skis on their packs. Due to the incredible snow conditions, we didn’t need ice axes, but we did see several crevasses right on the trail.

During the final part to Le Petite Bosse and then Mont Blanc, the ridge becomes quite sharp with a steep drop-off on both sides. It’s difficult to surpass another group or to cross with parties headed in the opposite direction.

Until now, the journey had consisted of friendly joking and banter. However, I was silenced by the altitude. It’s not just a shortness of breath; it’s your body telling you something is wrong, but it doesn’t know what. It’s difficult to explain, but you’ll know when you feel it.

It took us slightly less than 3 hours to cover the 800 meters (2,600 ft) of elevation to the Mont Blanc summit. It was a perfect summit moment. The views were spectacular, with almost no wind and no clouds. My only preoccupation was managing the ski down, as I was really feeling the altitude. Tagging a few 4,000-ers or staying in some high-altitude refuges might help with the acclimatization over the course of a season, but it’s hard to do in a day. Nobody had any desire for snacks. After a brief photo shoot and some congratulations, we started our 2,500-meter ski descent.

The Descent

The lower you get, the better you feel (I also didn’t drink enough water, more on that below). And it helps when the snow conditions are fluffy, dreamy powder, a gift from the heavens. It’s not all fun and games from here, though. The majority of the descent route is exposed to the massive seracs cascading off Mont Blanc. Taking into account our late start and the risk of icefall, as well as the last cable car scheduled at 5 p.m., we had to be fast.

As far as missing the Aiguille du Midi, the risk was only a couple of hours of great hiking, albeit in ski boots. But we were exhausted and still had to return to Cormayeur when it was all said and done.

The descent follows the glaciers all the way to about 2,550 meters, where you finally exit the Bossons glacier and start the traverse to the Midi mid-station. We were blessed to have this in nearly perfect conditions until the bottom of the skiing, just after the Grands Mulets refuge. It’s unusual to get such good conditions on the Mont Blanc, and even more remarkable to have them at such a low altitude that late in the day.

However, the descent was difficult to fully appreciate. As I mentioned, I had underestimated the effect of the altitude and had not consumed enough water, seeing as we had only climbed 800 meters. I began to get a headache during the descent and, by the time we reached the crossing of the Bossons Glacier, I had fully given up. I ended up taking ibuprofen, which fixed me up in minutes, so much so that I felt like I could have repeated the entire adventure over again. The lesson is to drink plenty of water and have ibuprofen on hand just in case.

Crossing the Bossons Glacier is a chore, especially after a big day. It’s essentially a giant pile of snow-covered ice balls, and you have to rope up to manage crevasse risk. Though it’s not a great distance, this section requires patience.

We arrived at the Midi at 4:55 p.m., five minutes before the last cable car. Could’ve skied more! To cap the day’s adventure, we finished with a typical Savoie dish: Tartiflette. Consisting almost entirely of potatoes, cream, and melted cheese, it’s a perfect way to recharge those batteries after an adventure.

Photo Gallery

Using the PeakVisor App

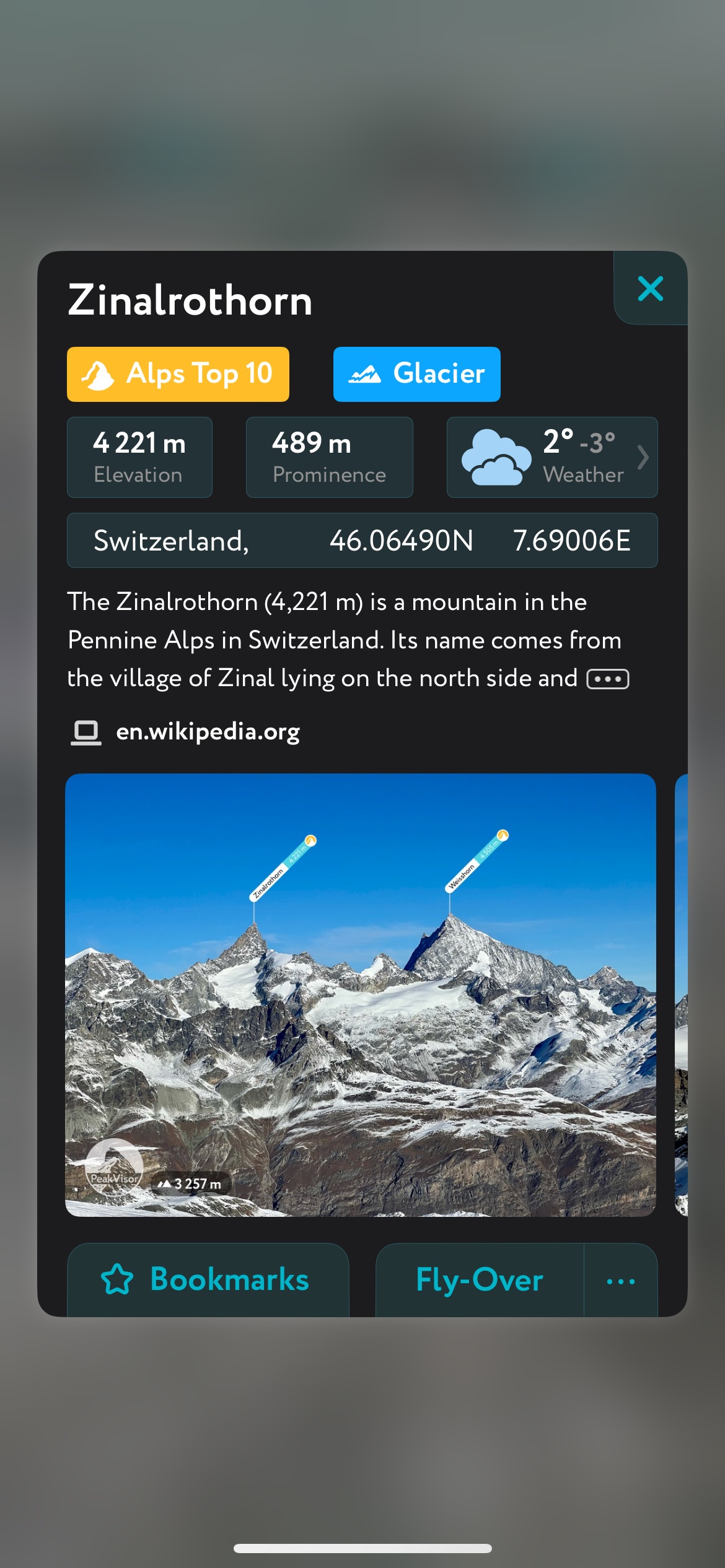

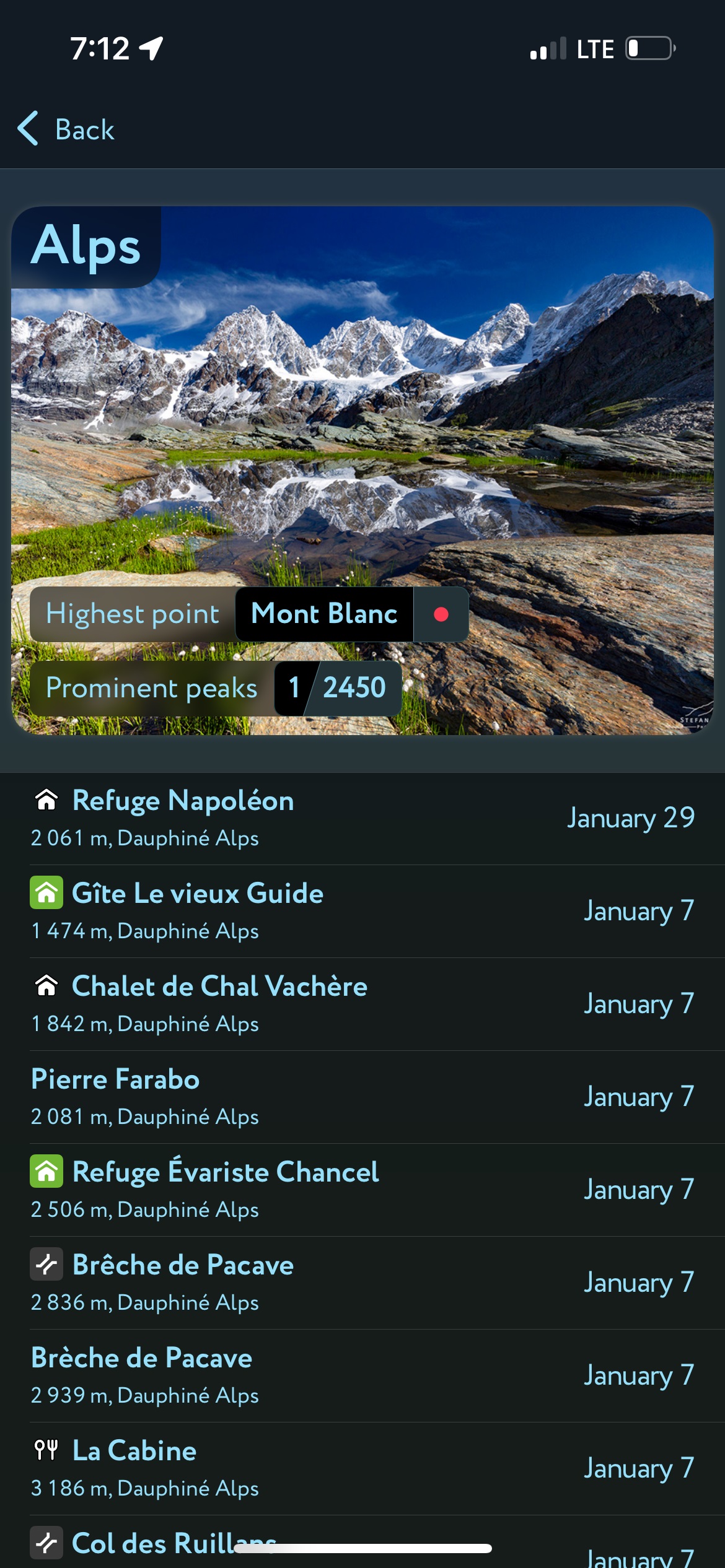

Interested in skiing? Check out the PeakVisor App. PeakVisor has been a leader in the augmented reality 3D mapping space for the better part of a decade. We’re the product of nearly a decade of effort from a small software studio smack dab in the middle of the Alps. Our detailed 3D maps are the perfect tool for hiking, biking, alpinism, and, most notably in the context of this article, skiing!

PeakVisor Features

In addition to the visually stunning maps, PeakVisor's advantage is its variety of tools for the backcountry:

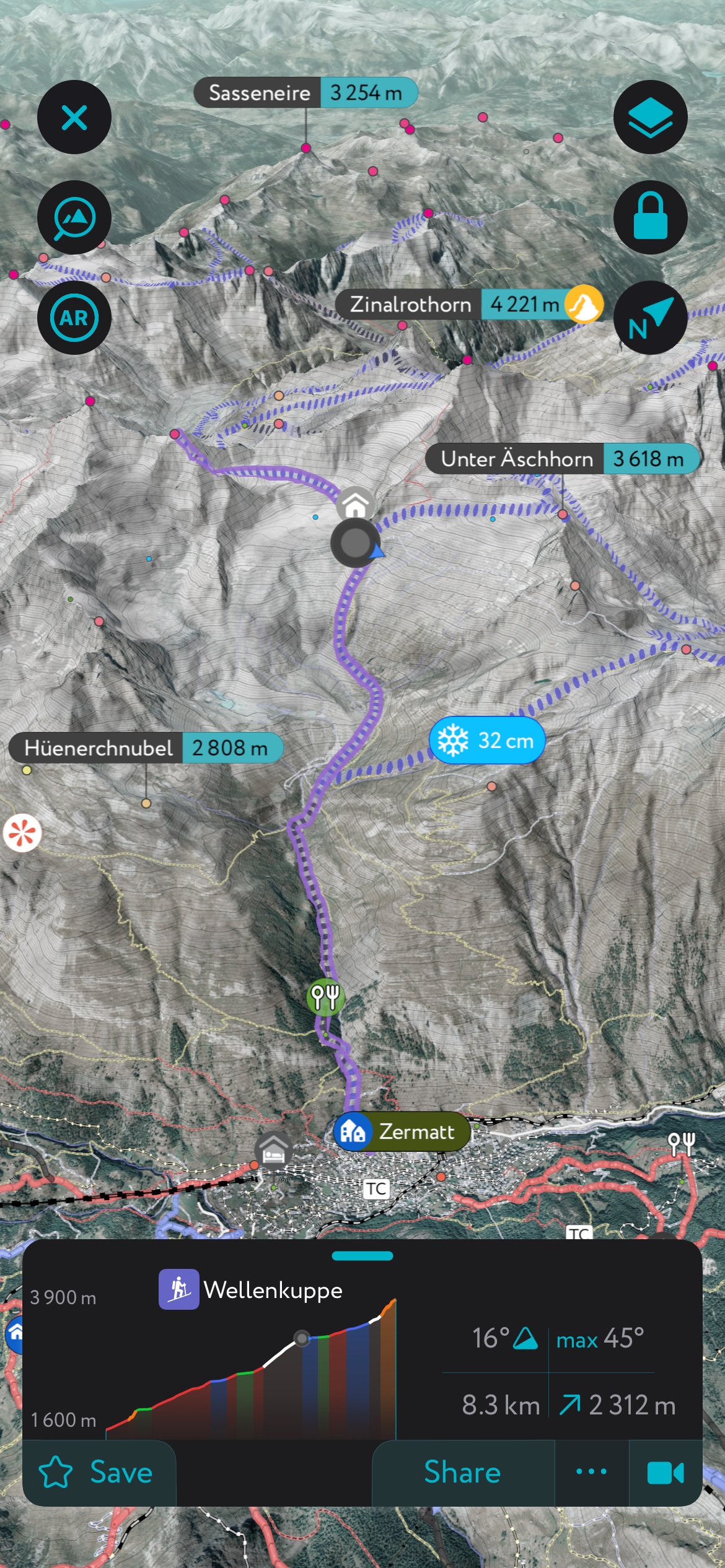

- Thousands of ski touring routes throughout North America and Europe.

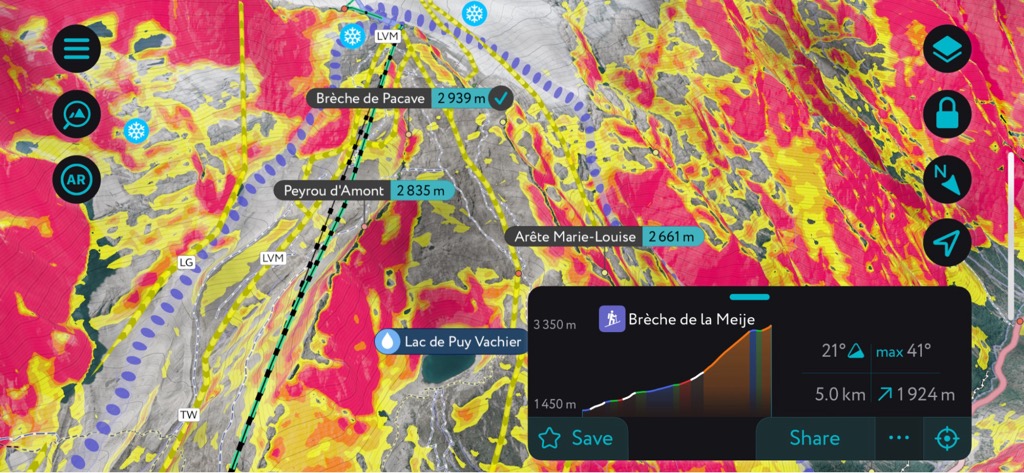

- Slope angles to help evaluate avalanche terrain.

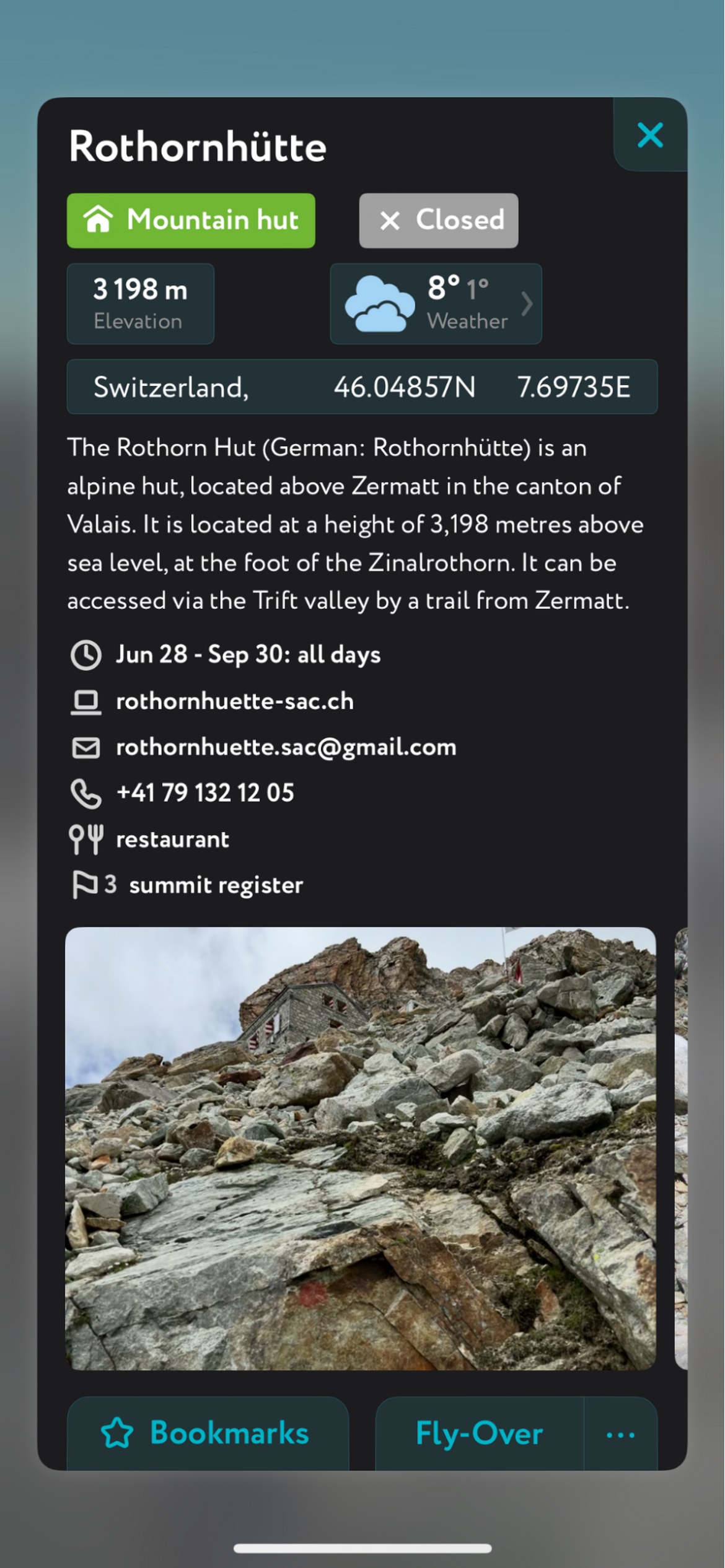

- Mountain hut schedules and contact info save the time and hassle of digging them up separately.

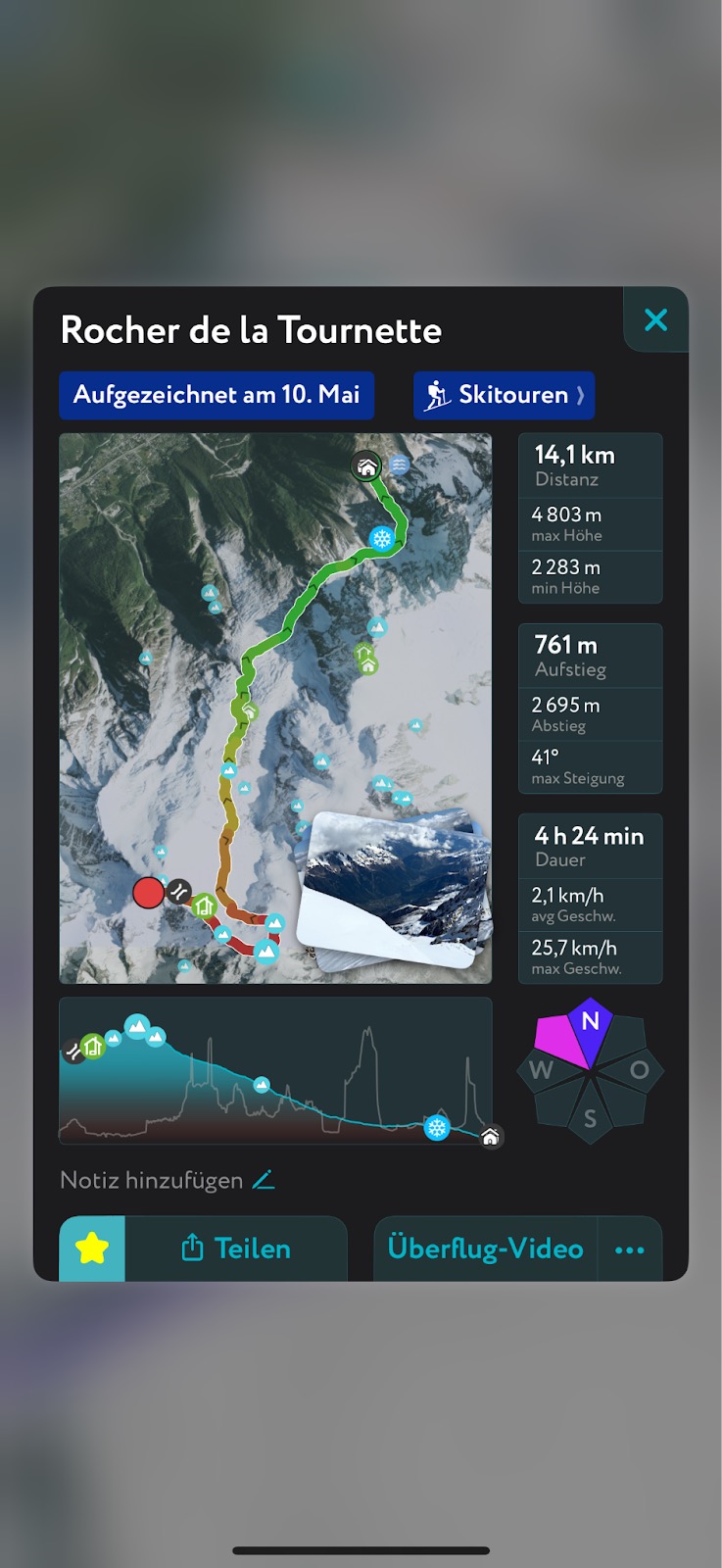

- The route finder feature generates a route for any location on the map. You can tap on the route to view it in more detail, including max and average slope angle, length, and elevation gain.

- Up-to-date snow depth readings from weather stations around the world.

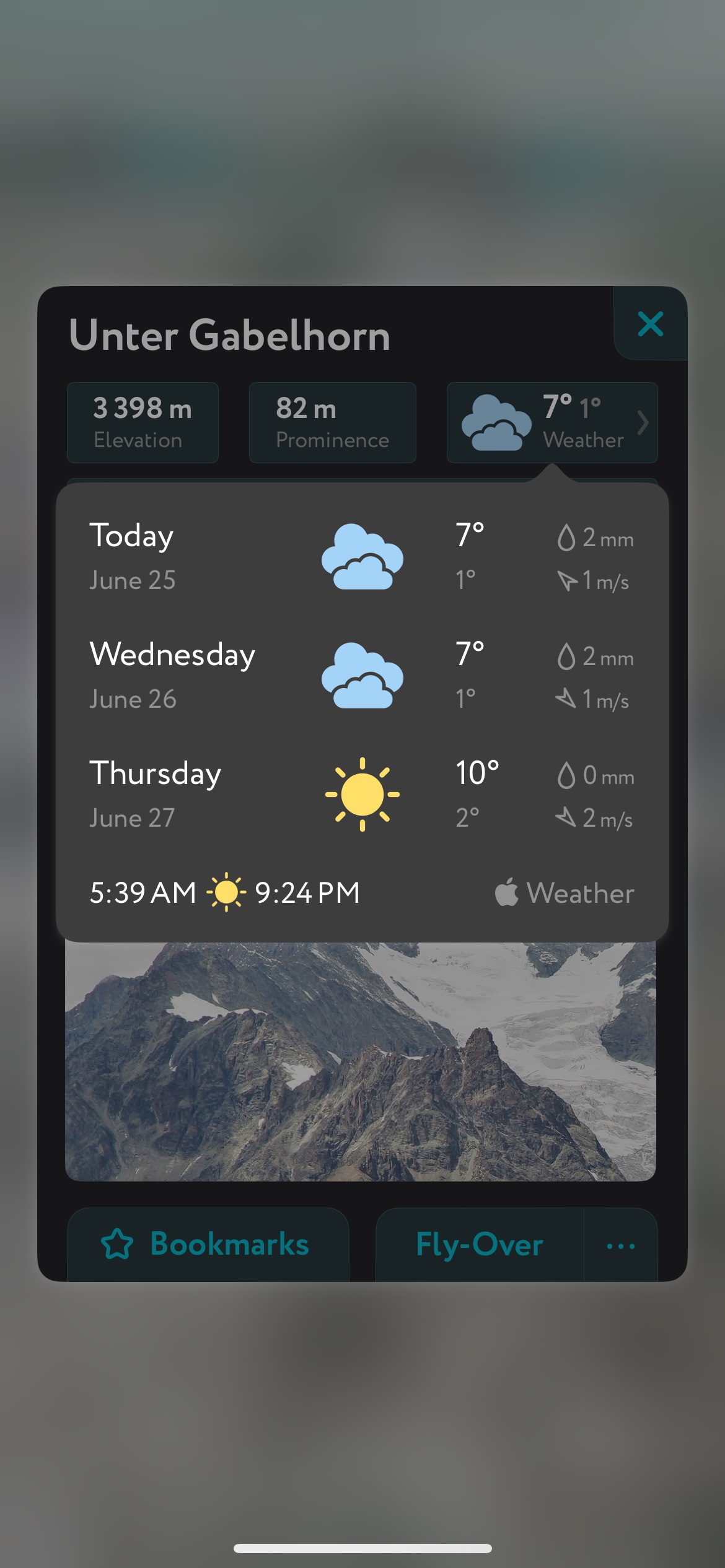

- A point weather forecast for any tap-able location on the map, tailored to the exact GPS location to account for local variations in elevation, aspect, etc., that are standard in the mountains.

- You can use our Ski Touring Map on your desktop to create GPX files for routes to follow later in the app.