Yosemite National Park is one of the largest, most famous, and widely visited national parks in the United States and, for that matter, the world. Home to numerous awe-inspiring granite formations like El Capitan (7,779 ft / 2,371 m), Half Dome (8,839 ft / 2,694 m), and Cathedral Peak (10,869 ft / 3,313 m), Yosemite Valley is considered the birthplace of American rock climbing and is arguably the most famous climbing destination out there.

The Valley lays claim to nearly 3,000 established climbing routes, primarily multi-pitch traditional routes but also sport, boulder, and alpine lines. In this article, we’ll cover everything you need to know about rock climbing in Yosemite, from the area’s climbing history to the most classic routes, tips for beginners, and more.

History of Yosemite Climbing

As rock climbing destinations go, perhaps no place in the world has a history as deep and rich as Yosemite Valley.

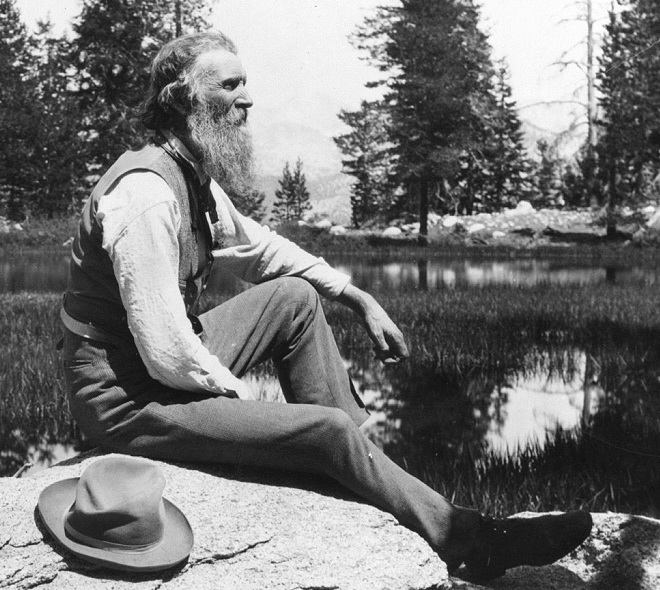

The region’s lore dates to the 1860s, when naturalist John Muir found himself working as a sheepherder in Yosemite’s Tuolumne Meadows. Circa 1869, Muir famously made the first ascent of Cathedral Peak, tackling the route in leather boots via an eponymous (and now-classic) 5.4 (French 4a). Six years later, Valley pioneer George Anderson made an initial (heavily aided) ascent of Half Dome. His line follows the modern-day Cables Route.

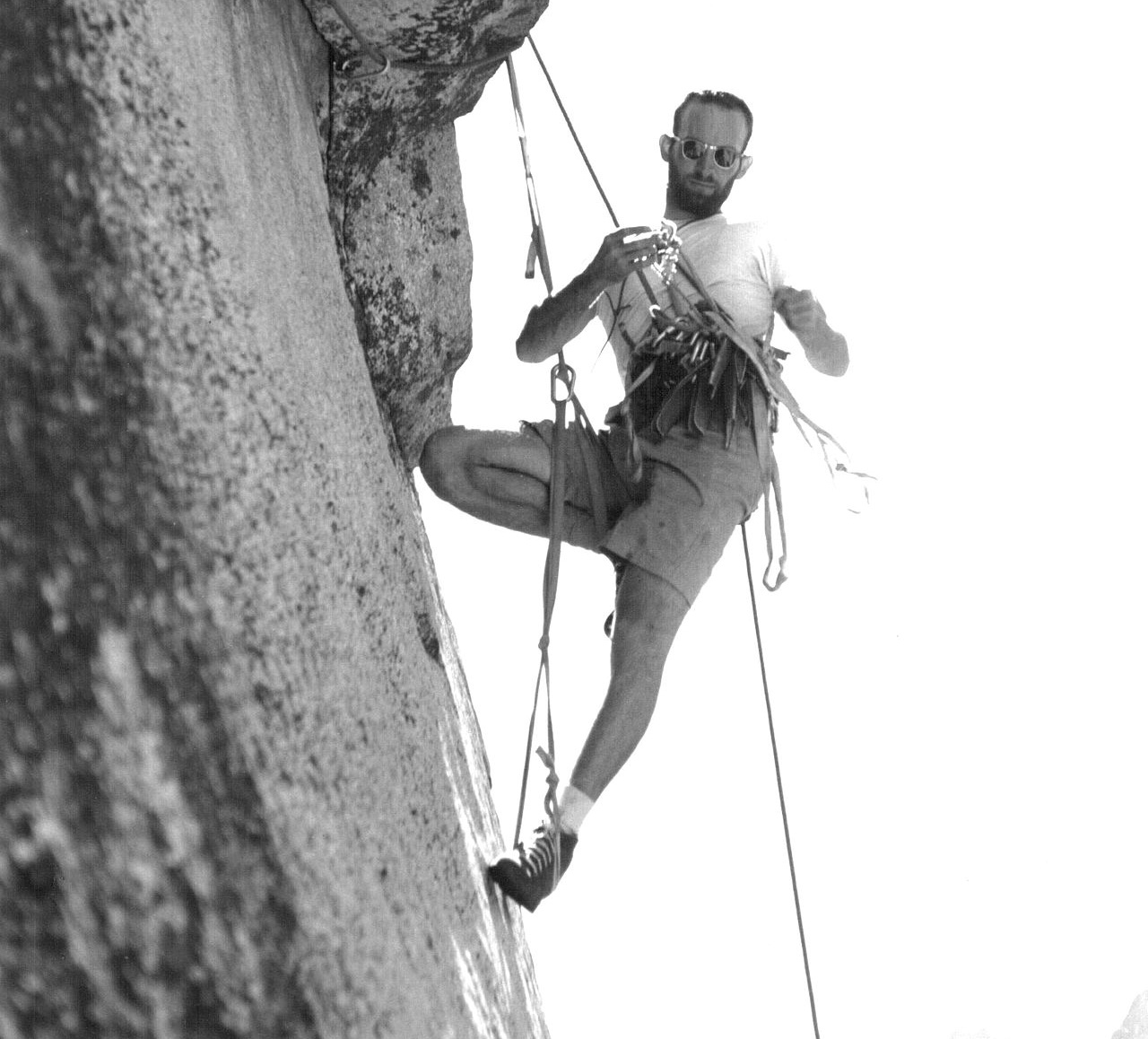

It wasn’t until the 20th century, however, that Yosemite rock climbing began in earnest. The 1940s saw John Salathé’s ascent of Lost Arrow Spire (7,369 ft / 2,246 m) using a new form of burly carbon steel piton (Lost Arrows), designed to be driven into harsh Yosemite granite without buckling.

Perhaps the most pivotal Yosemite climb, however, was the Royal Robbins-led climb of the Regular Northwest Face in 1957, the first Grade VI climb in the United States. This spectacular effort catalyzed an era of groundbreaking ascents (and one-upmanship) in the decades to come.

The following year, rambunctious hardman Warren Harding upped the ante with a bolt-happy ascent of El Capitan’s The Nose (VI 5.9 C2)(Fr. 5c), a 3,000-foot line that stands as the most iconic route in the Valley, perhaps the world. Other legendary efforts include Robins, Frost, and Pratt’s Salathé Wall (VI 5.9 C2 3500’)(Fr. 5c) in 1961 and the same crew (with the addition of Yvon Chouinard)’s 1964 ascent of the North America Wall (VI 5.8 C3 2800’)(Fr. 5.8).

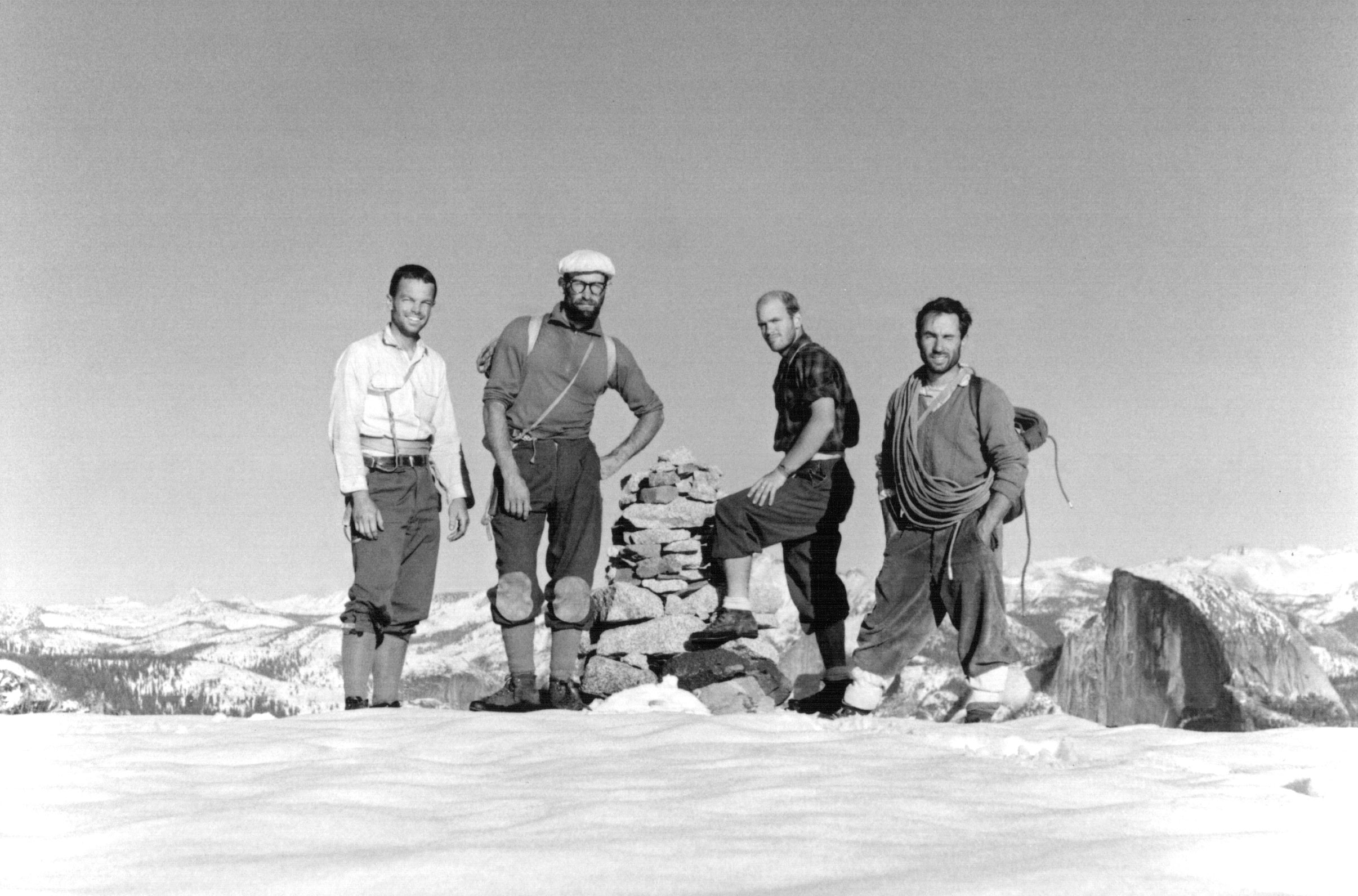

In the 1970s, the “Golden Age” of Yosemite climbing began in earnest, with accomplishments like Jim Birdwell, Billy Westbay, and John Long’s ascent of the Nose in a day (1975), the first free ascent of Astroman (IV 5.11c 1000’)(Fr. 6c+) by John Bachar, Long, and Ron Kauk (1975), and Kauk’s Midnight Lightning (V8)(Fr. 7B). Subsequent accomplishments largely revolved around freeing existing aid routes, like Todd Skinner and Paul Piana on the Salathé in 1988 and Lynn Hill on The Nose in 1993.

Yosemite climbing has continued to evolve in the 2000s in the realm of speed records and free solos, most recently Alex Honnold’s 2017 free solo of Freerider (VI 5.13a 3300’)(Fr. 8a), a feat famously documented in the Oscar-winning film Free Solo.

Another major accomplishment was Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s 2015 ascent of the 2,500-foot Dawn Wall, a line initially aided by Harding that went free for the pair at 5.14d, making it likely the hardest big wall in the world.

Classic Routes

Most of Yosemite’s most famous routes, including those discussed above, are committing big-wall endeavors. Climbs like these cannot be undertaken without extensive experience, training, and planning.

In addition to those mentioned in the previous section (The Nose, Freerider, Astroman, the Salathé Wall, the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome, and the Valley’s most famous boulder problem, Midnight Lightning), let’s cover a few more iconic climbs.

Snake Dike (III 5.7 R 2000’)(Fr. 5a) is the easiest technical route to the summit of Half Dome and a popular goal for Yosemite first-timers. Don’t be deceived by the 5.8 grade, however. This route is runout, slabby, and bold (denoted by the R after the technical rating). It was the site of a serious accident I covered last year, and this incident is not the first.

Royal Arches (III 2000’) is another ultra-classic. This route can be freed at 5.10- (Fr. 6a) or taken with a point of aid at 5.7 (Fr. 5a). Some equally worthy—but shorter—moderates for Yosemite newbies include The Nutcracker Suite (5.8)(Fr. 5b), the Southeast Buttress (5.6)(Fr. 4c) of Cathedral Peak, and the Central Pillar of Frenzy (5.9)(Fr. 5c).

Tips for Beginners in Yosemite

- Hit the Shoulder Season

Yosemite isn’t just popular for climbers. It’s one of the most visited parks in the country. Crowds are an issue, especially in the summer high season. Visit from April to May in the spring and late September to mid-November in the fall. These are the two best seasons to climb in Yosemite.

- Get Ready for Granite, Cracks, and Slab

Yosemite is characterized by rough, burly granite. Crack and slab techniques are a must-have to put down lines here. Work on your footwork and develop friction confidence on low-angle terrain. Crack-wise, you should prepare for everything from splitter finger cracks up to off-widths. Techniques like arm bars and chicken wings will come in handy.

Crack climbing requires intense strength, endurance, pain tolerance, and plain old black magic. Once you get the hang of it, though, it’s all you’ll ever want to climb - It’s Not All the Valley (or All Trad)

Yosemite Valley gets all the hype, but it’s a tiny percentage of the actual park (and the climbing in Yosemite). Particularly if you’re looking to change things up with some bolted routes or pebble wrestling, there are a number of other crags to check out, like crags around the Lower Merced, such as Parkline Slab and Reed’s Pinnacle. Jailhouse Rock—a couple of hours west—is another famous site for stiff sport climbing (5.12 and up).

Other Valley alternatives include zones like Hetch Hetchy and Tuolumne Meadows. For bouldering, check out spots in Southern Yosemite and, of course, Mountain Project’s dedicated guide to Yosemite Valley Bouldering.

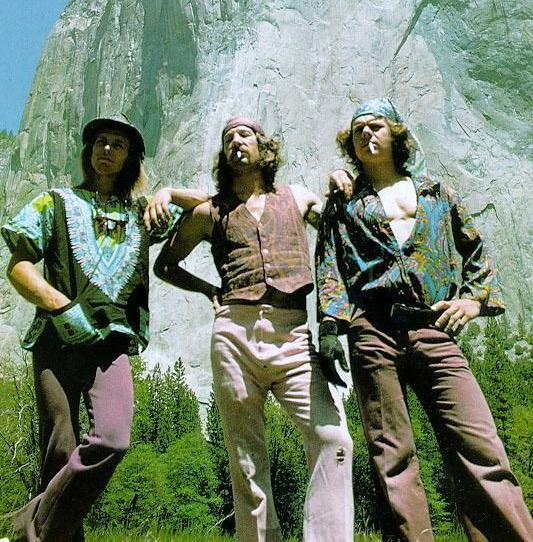

Billy Westbay, Jim Bridwell, and John Long in front of El Capitan after the first single-day ascent in 1975. StoneMastersPress, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons - Take it Easy

Yosemite climbing is hard. No question there. As the birthplace of the American grading system (YDS–Yosemite Decimal System), many of Yosemite’s routes were established decades ago, when—for example—5.10 (Fr. 6b) was the hardest grade in the country.

That doesn’t mean all grades in Yosemite are inaccurate, but there are plenty of climbs that would be considered heavily sandbagged by modern standards. If you’re a 5.10 leader, you should certainly be prepared to thrash pretty hard on Yosemite 5.9s. When eying up a Yosemite climb, aim for around two grades below your current lead grade.

A lifetime of granite slab climbing awaits climbers in Tuolumne Meadows On that note, don’t waste time trying to “warm up” on easy routes. Nothing is truly easy in Yosemite for a new Valley climber, and nothing’s worse than waiting in line for a climb you don’t really care about just to get sandbagged. Instead, choose a solid objective (or group of objectives) that fits your skill and experience level and get after it.

Many routes in Yosemite bear the scars, or presence of, old pitons. Pitons served to protect climbers against a fall and were also used as anchor points - Be Bear Aware

Black bears are a constant presence in Yosemite. Bears aren’t something to be afraid of—they rarely attack humans—but they will steal food and damage property. Be proactive. Store all smellables in bear canisters, bags, or bear boxes throughout the park. That’s not just food but anything with an odor (such as toothpaste, deodorant, and lotion).

NOTE: A car is NOT a bear container. Bears break into cars in Yosemite and other areas of the Sierra Nevada high country on an almost daily basis.

Bears in Yosemite are both massive and brown, but they are not ‘brown bears’ and are unlikely to hurt you. A steady diet of tourist trash has helped them attain their impressive proportions - think of your efforts at food storage as a fight against bear obesity - Be Ready for Ever Changing Weather

Many crags in Yosemite are alpine areas, and temperatures can change quickly. The Valley floor is already 4,000 feet (1,220 m) above sea level. Atop many of the formations, you’ll be thousands of feet higher. So don’t bank on warm, sunny weather, no matter what forecasts say. Weather can change depending on elevation and crag. No matter your objective, start early, pack layers, and always carry at least a basic shell in case of rain. With that said, although the weather can pivot on a dime, it is usually beautiful in Yosemite between April and November.

The Valley fills with snow each winter. However, sudden snow storms are also common in the shoulder seasons, when most climbers are active - Alpine Start!

Starting early is crucial to avoid the crowds and score the best conditions in Yosemite. Climbing in the offseason is a good start, but even then, you may be sharing routes with other parties. Make sure your tick list is long, so if some of your objectives are swamped, you still have plenty of options.

Getting a very early (or very late—bring a headlamp) start to your climb is the best way to avoid getting stuck behind another party on the wall. If you do get jammed up, don’t be afraid to let faster climbers pass you or ask to pass a slower party.

Rules and Regulations

As of 2021, Yosemite National Park implements a climbing permit for any parties planning to be on the wall overnight (or those camping at the base of Half Dome). The good news is that these permits are free, there’s no quota, and each permit can accommodate up to eight people in a single party.

You have to grab these permits in person, but you can do so 24/7 in front of the Climbing Management Office west of the Valley Visitor Center. For more information on current rules and regulations, such as bolting, fixing ropes, storing food, bouldering, and slacklining, see the Yosemite Climbing Association website.

Where to Stay

Free wilderness permits are required to camp anywhere in Yosemite’s wilderness areas. There is also (technically) a 30-night camping limit within the park each calendar year. From May 1 to September 15, that limit is 14 nights.

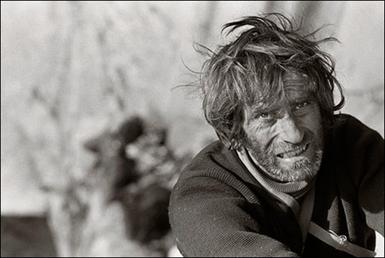

Historically, rock climbers in Yosemite have gravitated to Camp 4, the park’s unofficial “climber campground.” Even in 2023, Camp 4 is still the place for climbers who want the real “Yosemite dirtbag” experience. It’s the easiest way to meet partners, share beta, and be abreast of the latest news in the park. The campsite also hosts a “Climber Coffee” meeting at 9 a.m. every Sunday during the shoulder seasons and up in Tuolumne during the summer.

In addition to Camp 4, Yosemite National Park offers 12 other official campgrounds ranging in price, regulation, and size, with sites reservable up to six months in advance. For a quieter experience than the sometimes rowdy Camp 4, try places like the Upper and Lower Pines campgrounds.

It’s worth noting that from May through September, all campgrounds in Yosemite are available by reservation only. During the shoulder and off seasons, a few campgrounds—Camp 4, Hodgdon Meadow, and Wawona—offer sites on a first come, first serve basis.

NOTE: It’s best to purchase all food, fuel, and other supplies before arriving in Yosemite. You can buy just about anything you need in the park or surrounding areas, but you’ll end up paying an arm and a leg.