Traversing California’s Famed Wilderness Over Five Extraordinary Days

By Sergei Poljak

“When California slides into the ocean, as the mystics and statistics say it will, I predict this motel will still be standing until I pay my bill.”

- Warren Zevon, Desperados Under the Eves

Introduction

Central California’s Big Sur coastline has captivated America’s creative hearts and minds over the past century. John Steinbeck, considered America’s finest novelist, hailed from the Salinas Valley, just across the mountains. In his iconic stories of the California of old, he often featured the coastal town of Monterey, which loosely demarcates the northern end of Big Sur. In the 1960s, the hippies, descendants of Steinbeck’s original counterculture characters, made their way into the hills, drawn by positive vibes and isolation.

Today, Big Sur is becoming even less accessible. The legendary California 1, which snakes along Big Sur’s towering coastline cliffs, is steadily eroding. The road has been subject to frequent closures - the north had only just opened when we headed down here on June 2nd - and the southern portion is still closed, meaning it’s quite challenging to access Big Sur from Los Angeles and all other points south.

Geologically and climatically, Big Sur is in an ever-present state of upheaval. The range steadily moves northward (4.6 mm per year) as the Pacific plate drifts against the North American plate at the San Andreas Fault. Eventually, the range will be part of Alaska. Meanwhile, the Pacific Ocean’s foamy fangs steadily chew away at the crumbling cliffs along the shore. While the spiny ridges of Big Sur’s Ventana Wilderness will stick around for millions of years, it’s hard to see how the highway will last through my lifetime. Climatically, Big Sur is at immediate risk of long-term severe drought that threatens the ancient redwood groves.

Like the Mandalas of Buddhist Monks, Big Sur’s fleeting existence is all the more reason to value it. Yet, trudging into the untouched expanse of the Ventana Wilderness, there’s also a sense of permanence. Deep, shaded grooves in the mountains harbor ancient stands of redwood, many over 1,000 years old.

The Big Sur River canyon is a fairyland temple of soaring trees, chattering birds, and jumping trout. Sunny slopes are alive with Mediterranean shrubbery and Manzanita groves. The most exposed south faces become desert-like, with cacti and flowering Yucca plants.

A wildfire tore through the region just weeks after my last visit in April 2016. These were scorching crown fires fueled by record-high temperatures, half a decade of creeping drought, and a century of fire suppression policies. Most redwoods survived, albeit scathed. Some did not. Giant landslides followed the fires, engulfing trails and highways and cutting off Sykes Hot Springs for years.

I had already been entranced by the magic of Big Sur years earlier on a trip with college friends. I returned twice in the years afterward. I was curious: how had Big Sur changed? Had the Redwoods survived? With my attendance required at a good friend’s wedding in California, it seems only natural to share this extraordinary adventure with my girlfriend and Mom, the latter going for her first backpacking trip ever. The twist was that, instead of just Sykes, we would tackle an ambitious loop I had mapped out on PeakVisor before the trip. I knew it would be a full-value tour of the Ventana Wilderness, but I couldn’t have guessed just how full-value. For those curious about this magical realm, here’s the full story of our adventure.

Planning Our Route

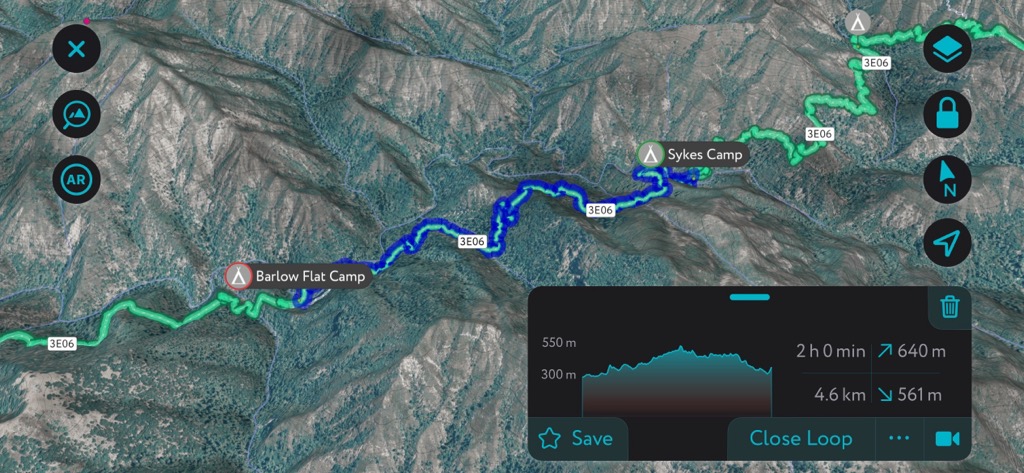

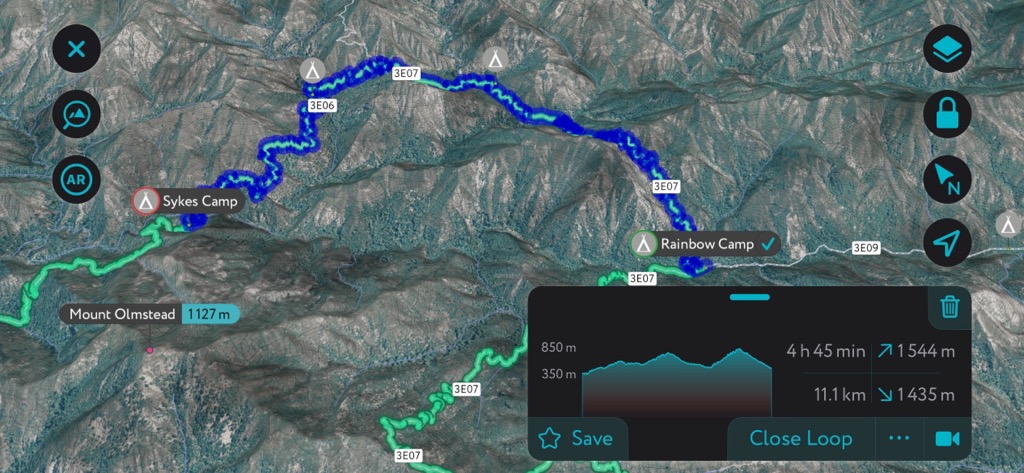

Many factors go into planning a backpacking trip: How long to go out for? How much distance to cover? Where to camp? How much food to carry? What’s the likely weather? While the PeakVisor app can’t answer all those questions, it offers a pretty darn good template for playing around with potential hiking routes. Here’s what I came up with:

Knowing we had a maximum of five days and would want to spend some time at Sykes Hot Spring, a 55 km (34 mi) route seemed reasonable. The terrain here is rugged, with continuous steep ups and downs, so an average of 11 km per day seemed achievable. It’s easy to plan on the app by just setting a destination and extending that destination along possible campsites. I named our loop the “Sykes Loop,” but the actual trails are, in order:

- The Pine Ridge Trail

- The Big Sur Trail

- The North Coast Ridge Fire Road

- The Terrace Creek Trail

- And back to the Pine Ridge Trail for the finish

There was a lot of possible variation within this loop, as far as daily distance and campsites are concerned. In fact, we could have done the same loop and stayed at entirely different campsites each night. The app is also helpful for seeing which campsites are on rivers (nearly all of them) and for daily elevation gains. The app tends to overestimate elevation gain in terrain with lots of steep undulations. In total, we did about 2700 m (8,858 ft) over the five days.

We planned for ticks and poison oak, both of which are abundant on this trail, by wearing long pants and long-sleeved shirts most of the time. Unfortunately, we did not plan for the biting flies, which turned out to be the most horrendous any of us had ever experienced.

It’s important to stop at the Big Sur Station when you arrive. We grabbed a fire permit, which I believe you are supposed to have even for a cookstove. The ranger offered up some helpful details, such as the permitted reroute at Barlow Flat and the water tank at Cold Spring Camp. I was skeptical of the road section of the hike, but he assured me of its splendor. I was also curious whether folks had yet to do the loop this year, and he affirmed that at least a few parties had done it the previous weekend without incident.

Getting to Big Sur

Getting to Big Sur is no walk in the park these days. The fires come, the rains fall, and the muds slide. The highway gets piled high with debris or washes away into the sea. Either way, parts of Highway 1 have been closed on and off for the last several years.

It’s important to always check the Caltrans website (type in “1” and look at “Central California” to get the information for Big Sur). The highway has been closed from the south for much of the past several years, so flying into San Francisco and coming in from the north is your best bet. Nevertheless, as of June 2024, several sections of the road had been reduced to one lane with traffic lights due to damage.

Day 1 - Barlow Flats

The first day at Big Sur is always partly the magnanimous drive into the place on the famous Highway 1. Give yourself a half day for the drive down from San Francisco because you’ll want to stop, breathe some Pacific air, and have a look around at the spine-tingling precipices of the central coastlands.

The parking lot for Pine Ridge Trail hikers is just down from the “Big Sur Station,” which is convenient for those looking to pop in with any questions. Parking is $10 a day, and we almost forgot/didn’t realize it as we started hiking. You will almost certainly get a ticket, so don’t skimp out.

Like a herd of turtles, our crew finally began moving around 3 p.m. It wasn’t long, however, before Anna (thankfully) realized that we had forgotten the fuel for our stove. I doubled back to grab it, and we were finally on our way.

The very first part of the hike is through the Pfeiffer Big Sur Campground. As soon as you reach the forest, you begin to climb. The human realm slowly but surely fades away into the distance. The sounds of cars, campers, and construction become a distant memory, replaced by the hum of the magic forest. You quickly become normalized to the minute sounds of lizards scurrying away before your footfalls and shrubs dancing in the Pacific Breeze.

At this point, the trail is broad and well-trodden, so there is relatively little brushing against shrubs and grasses. Nevertheless, we still managed to collect one tick amongst our party, which embedded itself behind Mom’s ear. Fortunately, she could feel it, and we plucked it away before any diseases could be transmitted.

The Pine Ridge Trail doesn’t follow a ridge and doesn’t have too many pines besides the towering redwoods. Up to Sykes Camp, it follows along well above the Big Sur River. The trail is a series of ravines, some with rushing mountain streams, colonized by ancient redwood groves. Meanwhile, the sun-drenched faces are plastered with scented Mediterranean greenery. If nothing else, this is hands-down the best-smelling trail I’ve ever hiked.

Every part of this loop is challenging. Arriving at Barlow certainly wasn’t the hardest day of the trip, but it wasn’t easy. We did almost 600 m (~2000 ft) of elevation gain over 15.5 km (10 mi), although that included my jog back to get the fuel. Therefore, expect about four hours of solid hiking to reach Barlow with a heavy pack on your back.

Barlow Flats is a veritable temple of a campsite set amidst a large redwood grove along the Big Sur River. The swimming hole here is one of the best we encountered in the Ventana Wilderness, though there are a few deeper and sunnier holes upriver from the hot spring at Sykes. Effervescent orange salamanders scurried among the boulders at the river’s bottom, and trout jumped out of the water to catch flies, of which there was no shortage.

A dozen or so large, flat campsites are scattered along the river, some with established fire rings and even camp furniture, like benches cut out from old driftwood and fallen redwoods. There was even a tiny cutout on a fallen tree meant specifically for your cooking setup. Like Sykes and Terrace Creek, the campsite also conveniently has a toilet.

We had the place nearly to ourselves (it was a weekday), but this is likely the most popular campsite in the Ventana Wilderness. Prepare to trek a bit further to find firewood.

Day 2 - Sykes Hot Springs

After a night of that sort of profound sleep that only seems achievable after a day of backpacking, we were ready to check out the legendary Sykes Hot Spring. A landslide destroyed a section of trail between Barlow Flat and Sykes camp, and the reroute now takes hikers through Barlow Flat for two crossings of the Big Sur River before climbing back up to rejoin the trail.

It’s only about 5 km (3 mi) to Sykes, so we envisioned this as the most leisurely day of the trip, a chance to hang out and bask in the aura of the sacred springs. After culling that first tick from behind Mom’s ear, we set off into the already steamy morning. A heatwave was forecast, and it appeared to have arrived.

As expected, the jaunt to Sykes camp was straightforward, and we secured a lovely campsite closest to the springs. In hindsight, the best campsites are actually away from the spring to the right of the Pine Ridge trail as you arrive at the Big Sur River. You’ll have more solitude, a great swimming hole, and only a few minutes longer to walk to the springs.

Everything was still good and dandy except for the flies, which had now reached an unimaginable crescendo. Out of necessity, we ate lunch crammed inside one of our tents (this would become tradition over the next few days). Afterward, we attempted the springs, but the flies were unbearable, and we gave up. They must have been attracted to the constant human presence at the hot springs because their local abundance was like a swarming, buzzing, biting haze. Any uncovered flesh was liable to be violated at a moment’s notice.

The flies operated on a timetable. They would get tired and settle down in the evening and during the night. I’m convinced the heat would stimulate them because their presence became increasingly ubiquitous as the heatwave intensified. Whereas they were done by 7 p.m. the first night, they didn’t die down until 9 p.m. by the end of our walk and would be in full force by breakfast. Fortunately, there was respite, and after dinner, we had no problem walking down to the springs for a nighttime soak.

There’s definitely been some changes at Sykes. The springs have been rebuilt since the winter of 2022-23 flooding. They’re a bit smaller than I remember, but still delightful. It seems like there’s less vegetation and more mud around as well. The bottom of the third pool was filled with debris. It might take some time and effort for everything to recover to its former glory. I’m just grateful for the efforts of many volunteers who have already done such an excellent job revitalizing this sacred retreat.

Day 3 - Rainbow Camp

The following morning, the crew—especially yours truly—all smelt of sulfur. But we were refreshed and ready to tackle some distance.

Crossing the river out of Sykes Camp, we ran into some nudies heading to the springs. It wasn’t even 10 a.m., and the flies were already out in full force, so we weren’t sure how long they would last with so much flesh ready for the taking.

The trail ascends steeply out of Sykes and flips over to a southerly aspect. Here, we made our first critical error of the trip. We started far too late, and it was already boiling hot along the exposed trail. We made it to Redwood Camp, about 3 km (2 mi) past Sykes, where we refilled water, cooled off in the stream, and ogled at the “Mother Tree,” one of the oldest and largest redwoods in the Ventana Wilderness.

The next portion of the trail, to Cienaga Camp, proved far more brutal than the first. As soon as we hopped onto the Big Sur Trail, the path became simultaneously more exposed and more overgrown. There are no trees for shade, but brush has proliferated ecstatically around the trail, and things get bushwacky. You’re also ascending steeply to cross over a pass to Cienaga Camp; heatstroke was on our minds when we reached the top.

The fire’s damage was far more visible on this hot ridge, and many hardy trees that hitherto managed to survive on the ridgeline had been incinerated beyond repair. Other redwoods were vociferously shooting new growth from the trunk and roots but were now clearly vulnerable to subsequent fires.

After the pass, descending to Cienaga was a bushwack through poison oak thickets. There was no avoiding it, and we knew we would have to scrub off in the next stream or suffer the devil’s wrath. At Cienaga, we submerged ourselves in the cold but refreshing waters. In addition to lowering our body temperatures by degrees, we thoroughly scrubbed all clothing. After a hearty lunch, we were back on the trail to clear a 400 m (1,300 ft) climb before descending to Rainbow Camp.

We were met with a pleasant surprise, as the trail had been meticulously cleared in recent months. Evidently, it had been nearly impassable; swept aside were massive bundles of scrub that had required a chainsaw. Plus, it was north-facing and shaded by dense vegetation, so we didn’t see the sun on this climb. Descending the other side of the ridge, we were back in the heat. It was intense, even while walking down the mountain.

At last, the sight of Rainbow Camp was enough to make it all worth it. It’s one of the most proud campsites in Ventana Wilderness, and we had it all to ourselves. Without further ado, we plopped into the shallow swimming hole next to camp and lowered our body temperatures back down to normal. We admired the lush greenery and broad trees, which were surprisingly not redwoods. Dinner was deliciously salty Shin Black Ramyun with mushrooms and snow peas (we don’t mess around with our camp dinners).

Day 4 was planned to be our longest, most demanding day, and after climbing in the heat to Rainbow, we all knew it would be brutal. This would necessitate an early start, so instead of some campfire moments, we said good night extra early.

Day 4 - Rainbow Camp to Cold Spring to Terrace Creek

Most unfortunately, my snooze did not last long. I awoke at about one in the morning with emergency levels of gastrointestinal discomfort. We won’t go into the gritty details, but I wiled away the rest of the night outside the tent and was in a significantly weaker state by dawn. Had I caught the dreaded giardia? We were filtering all of our water with my excellent ceramic pump filter.

I realized the culprit must have been the cheddar cheese we had consumed voraciously at lunch the day before. I’d had this reaction to lactose twice before, but only from drinking milk and never from eating cheese, yogurt, or any other dairy product. I knew that I was going to be in for a horrible 24 hours. We absolutely had to get out as we had to be in Lake Tahoe, five hours away, by Thursday night for a wedding. I wasn’t in imminent danger of death, just horrible discomfort. The only option was to get as far as we could.

By 8 a.m., it was already sultry, and the flies were out in full force. We plucked another tick from Mom’s belly button, then hit the road. From Rainbow Camp, we immediately began slogging up switchbacks. I carried out the rear guard. The heat was relentless; it was like a furnace in the sun. There was no evidence whatsoever of the vast, cold Pacific Ocean that lay just a few kilometers away. There was nary a breeze as we ascended about 900 m (3000 ft) to Cold Spring Camp. It would have been a strenuous hike in any condition, but wracked by nausea and having consumed no food in 18 hours, it was torture.

We reached the parched expanse of Cold Spring Camp around noon, as the sun reached its zenith in the sky. The camp is little more than a dirt parking lot at the end of a fire road, but the water tank is a savior. We soaked ourselves under the surprisingly cold water and quickly pitched a tent to escape the teeming mass of biting flies. The entire contents of my gut felt like a taut balloon, but with no life; it was as if my digestive system had simply ceased to exist. I suppose by this time, my body had reverted to consuming its fat reserves because there were certainly no calories left from food.

The crew was dreading the next section because it was a fire road entirely exposed to the blazing dragon that was the sun. The road traversed the ridge for close to 10 km (6.2 mi) before we split off down the Terrace Creek Trail. Indeed, it couldn’t have been hotter. We were 1,000 m (3,300 ft) above the Pacific Ocean, gazing straight down at its vast expanse, but the air didn’t stir. The views were incredible, though.

Fortunately for the whole team, the road was basically a continuous slight decline. It was so hot that I don’t think I would have been able to do a bunch of ups and downs. We rolled into Terrace Creek Camp 4.5 hours later. At times during the day, I had genuinely wondered if I would make it to Terrace. We could have stopped at other camps if necessary, but with serious disadvantages (farther away from the car, no water, etc.). I was exhausted once we arrived and immediately fell into a deep sleep for 12 hours after setting up the tent.

Day 5 - Terrace Back to the Parking

I have rarely, if ever, slept for as many hours in a row as I did on this night. In the previous 36 hours, I hadn’t eaten anything but a few gummy bears. I had hiked 23 km (14 mi) with 900 m (3,000 ft) of elevation gain wearing a heavy pack. I still wasn’t remotely hungry, but I did feel well-rested and not nauseous. Honestly, I felt like a new person waking up to greet the world; it was the best I could have asked for.

By the time we left, the flies were already brutal. The crew was tired but in great spirits because we were all so jazzed to escape the heat, the flies, the mosquitos, and the ticks. Upon leaving Terrace Creek, we saw our first other person in two days; it had been all solitude on the trail since Sykes Camp.

Alas, the proverbial storm had ended. The trail was smooth sailing. Even the flies disappeared as we descended out of the mountains. The day was much cooler, and a steady ocean breeze emanated from the Pacific. We were back on north-facing terrain again, where the sun was a bit less menacing. It was downhill nearly the whole way, and we knocked out the remaining 9 km (5.5 mi) to the car in just over two hours.

We stopped at Point Lobos Park on the way out, which we highly recommend. You can park on the road for free or pay $10. It’s the best place to see Sea Otters in Big Sur. The docents already had a scope trained upon a family of three lounging in the kelp. Mom was ecstatic.

Conclusion

The Ventana Wilderness is one of those places in the Universe that is truly enchanted. Some might call it a vortex. From the scented herbs to the cathedral-esque redwood groves to the crystal-clear swimming holes, it’s one of a kind.

That said, it’s no walk in the park, so to speak. After the weekend wedding, my girlfriend and I followed Big Sur up with the Lost Coast. Now, there is type one fun sort of backpacking! If you’re looking for a mellow backpacking trip, you’d better look right past the deeper sections of the Ventana Wilderness. Last but not least, kudos to Mom for crushing it on her first backpacking trip!