A Trip Report from One of the World’s Most Unique Backcountry Routes

Introducing the Lost Coast

Once upon a time, white men discovered gold in California, and all hell broke loose. They milked the land for all it was worth in the name of progress and manifest destiny. They built railroads and then highways crisscrossing the state to transport goods, services, and people. The famous California 1 traverses nearly the entire coast, branching off to the 101 at Leggett and the I5 at San Clemente. Just one section of coastline was too rugged for infrastructure: they dubbed this the Lost Coast.

Well, their loss is our gain. Flanked by the imposing King Range on one side and the wild and untamed Pacific Ocean on the other, the Lost Coast is California's only significant remnant of a wild seashore.

Besides being untouched by man's wicked hand, the environment here is preternaturally beautiful. The Pacific, mired in a state of perennial unrest, ranges in hue from mesmerizing cerulean to steely gray. When a setting sun and a few clouds enter the picture, any color of the rainbow is possible. The coastal soundtrack is the endless din of crashing waves against rounded pebbles.

Straddling the sandy beaches to the east are the stoic but eroding cliffs at the base of the King Range. In some places, landslides have deposited huge swaths of the range directly onto the beach. In others, mountain streams flow into the sea, surrounded by moss-covered trees that are surely home to fairies.

Admittedly, we could not have had better luck with the weather. Hardly an ounce of fog touched the coast during the entirety of our four-day hike. I didn’t have a thermometer, but I would guess that daytime temperatures hovered around 68℉ (20℃). Meanwhile, nights dropped to around 51℉ (10.6℃), the ocean temperature at the time, according to Surf-forecast. I have heard horror stories of constant fog, and honestly, I expected it to be foggy most of the time. Another thing to watch out for is wind, usually from the northwest. It’s one of the main reasons people typically hike north to south.

We hiked the trail within ten days of the summer solstice, so the sun was blazing. Moreover, most of the beach faces south along this section of the coast, so you’ll be getting hammered by the sun no matter what time of year. Most people we encountered were enveloped in pants, long sleeves, all manner of head scarves, oversized hats, and even gloves.

Notable wildlife sightings included adorable elephant seals, a mama deer with two baby fawns, and multiple dead octopi washed up on shore. We didn’t have much luck with the tidal pools but saw some starfish here and there. We had perfect blue skies and comfortable warmth all day, every day. Even better, nights were cool, almost cold, which made for heavenly sleeping conditions.

The Lost Coast is beautiful, and our trip worked out remarkably well—it really was exceptional. As a result, this trip will always be imprinted in my memory. Here’s the lowdown on our journey, from planning to finish.

Permits

The two big hassles during any Lost Coast backpacking trip are permits and shuttles. There’s also timing the tides, but that’s more of a challenge than a hassle.

The United States BLM offers permits online. Follow this link to the website. They’re currently $6 per hiker but will soon go up to $18.

The permits are released on a rolling basis three months in advance. So, on June 27th, the permits for September 27th will open up, and so on. There are 60 spots a day from May 15th to September 15th and 30 a day during the rest of the year. Two walk-up permits are also available daily on a first-come, first-serve basis.

The permits can be tricky. There are a couple of options. You can plan your trip three months in advance and log on in the morning to secure permits. Or, if you're flexible, you can always find some random dates available, especially mid-week. There are also often permits available the day of, probably due to sudden cancelations.

Don’t try to go without a permit. The permits are meant to limit overcrowding in this national treasure. Besides, during our trip, there were two rangers walking around questioning everybody. Nice dudes, but you gotta have your permit.

Shuttles

Nearly everybody hikes the Lost Coast one-way, from north to south. If you decide to complete the trail this way, you must arrange a shuttle with your own car or with one of the local shuttle operators. The cost is about $100 per person. However, there is a three-person minimum, so you’re responsible for paying for the extra seats if the minimum is not met that day.

It’s not cheap, but it’s a nearly two-hour drive from Black Sands Beach to Mattole. With a group of three or four, it could be economical to check Craigslist. Locals will sometimes offer shuttles in their personal vehicles.

You can always hike back if you don’t want to bother with the shuttle, but it will add at least a couple of days to your trip. Better yet, you can do what we did: camp halfway, do the remaining coast as an out-and-back, and return to your starting point.

Tides

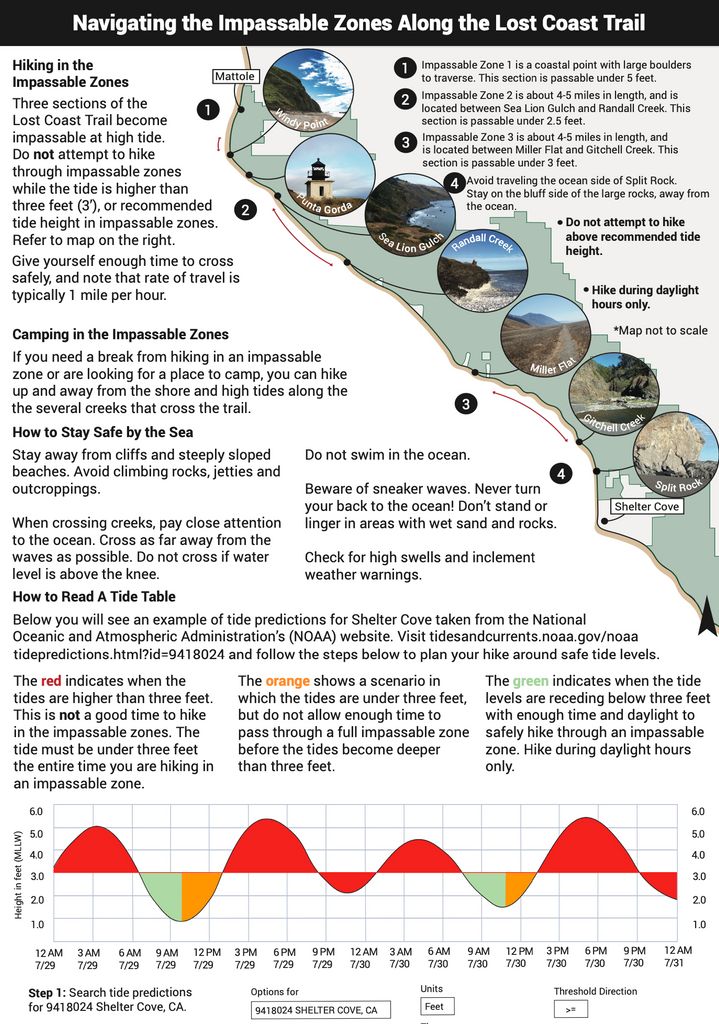

After you sign up for your permit, the BLM will send you a link to a few important videos about your hike (click here to watch one of their videos on tidal and ocean safety). One of these concerns is navigating the tides and “impassable zones” along the coast. A couple of three or four-mile stretches of the coastline must be completed within a few hours of low tide. Once the tide is higher than three feet or so, it becomes treacherous to pass through these choke points.

The BLM does not overstate the seriousness of making it through on time. The coast here is rough and powerful; waves toss boulders around like sand, and the beach is littered with jagged rocks.

Here’s what you need to know about the tides, according to the BLM:

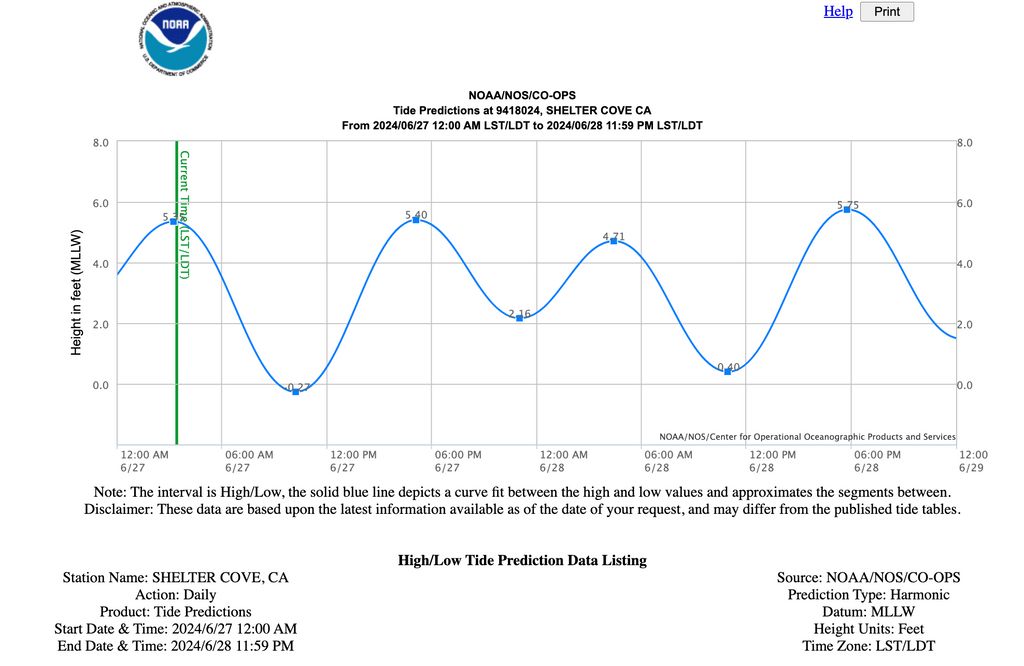

We used the NOAA tide charts to navigate our journey along the coast. Here’s an example:

Much of the trip planning revolves around making it through during low tide. For example, depending on the tides during your hike, you may get up to start hiking very early and finish by noon. Or, you might begin in the afternoon. Fortunately, because the tide cycles every 12 hours, there will always be a window during daylight.

Our Lost Coast Itinerary

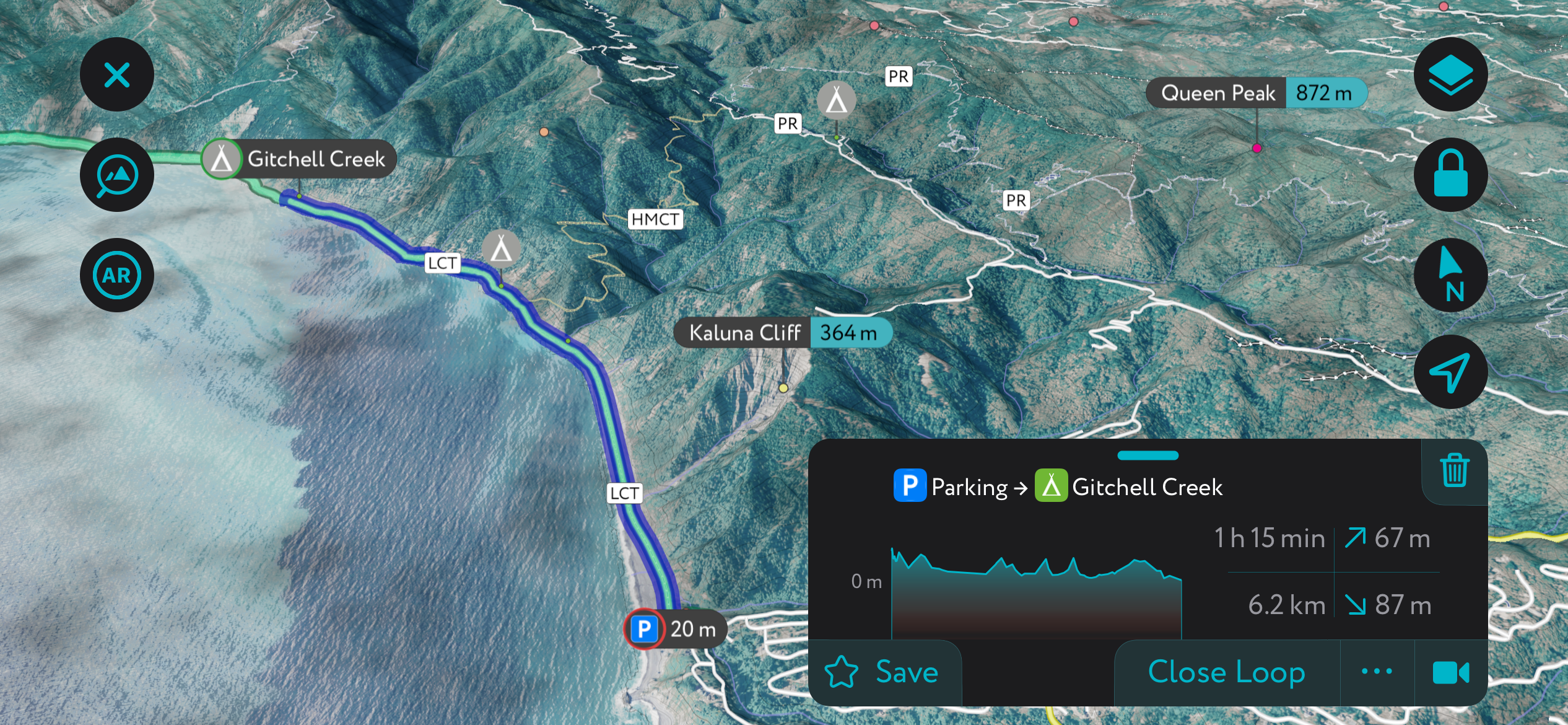

As I’ve mentioned, our Lost Coast itinerary is different than most. While almost everybody starts at Mattole Campground in the north, we began at Shelter Cove/Black Sands Beach in the south.

We didn’t want to deal with shuttles, which would have added an extra two or three hundred dollars to the cost of the trip. Plus, as we came from San Fransisco, Shelter Cove was a closer drive than Mattole.

Before starting the hike, we spent the night at Wailaki campground, also operated by the BLM. It’s a beautiful car camping spot with fire rings and grills.

The next day, we stopped at the Shelter Cove General Store to rent a bear canister, which is required for hiking the Lost Coast. While I love a good family business, I can’t recommend this place: they charged us $20 for the heaviest bear canister you can imagine. The King Range Visitor Center in Whitehorn rents them for $5, so it’s worth stopping, although it’s out of the way if you’re starting at Mattole and not dropping a car. I'm unsure if there are places to rent around Mattole.

We dropped our car off at the Black Sands Beach parking area. If the actual parking lot is overflowing, as it was when we went, there is plenty of overflow parking along the street.

We stayed at Gitchell Creek for the first night and Big Flat (also known as Miller Flat) for nights two and three, before returning to Black Sands Beach on the fourth day. Controversial, I know, but I loved doing the trip this way. We still managed to see almost all of the Lost Coast during a long day hike on day three, which was possible because we left our packs at Big Flat. It was also lovely to take a break from the drudgery of packing and setting up camp, at least for a day (we’d just completed a strenuous backpacking trip in Big Sur).

In total, we hiked over 40 miles (64 km), but only 18 of these miles were with a heavy pack. Still, contrary to our expectations after what we read online, this felt like a very chill backpacking trip. Walking in the sand is not as hard as they make it out to be, mostly because you don’t have to do massive elevation climbs like on other backpacking trips.

Day 1 - Shelter Cove to Gitchell Creek

We started down Black Sands Beach with exceptionally hefty packs but giddy with excitement. With so much sun, the beauty was awe-inspiring as soon as we dropped down onto the beach.

We expected the hiking to be more strenuous than it was, and this section was the most complained-about. Between Gitchell Creek and the southern end of the trail, it’s a slog through soft sand. Nevertheless, it’s nothing compared to climbing mountains with a heavy pack, let me tell you. It can get hot in the sun without fog, but the ocean breeze filtering in off the Pacific is the very essence of life. Still, there was plenty of time for a short nap behind the Split Rock.

A few hours later, we cruised into Gitchell Creek. It’s a beautiful campground with a protected, fairy-den-like site behind the pile of drifted logs.

The sites in the fairy forest along the creek were already occupied, so we opted for the beach. If you can get the protected sites, go for it. Camping on the beach is a bit exposed; there was a minor wind even as we set up the tent for the night. Some pesky sand grains definitely made it into our food and were loudly pulverized between my teeth.

The wind was a minor inconvenience that night. We later heard that it was gusting much harder on the north side above Big Flat. Another win for us starting on the south.

Sleeping to the rhythm of the maniacal Pacific Ocean is also an experience. It’s loud but reassuring, like a Spotify deep sleep playlist turned up full blast at a movie theater.

Day 2 - Gitchell Creek to Big Flat

After big dreams to the beat of the big surf, it was time to mosey on over to Big Flat. We leisurely packed up camp, moving as slowly as humanly possible while still making the tide for the impassable zone.

Going through this section was substantially easier. The sand was wet and firm; no sinking. Thus, crossing the four miles of exposed coastline took less than two hours. In our experience, the impassable zone south of Big Flat wasn’t too difficult, and we made it across with plenty of time (the zone between Punta Gorda and Randall Creek is more serious).

The four-mile-long constriction is a spectacle of erosion. The flanks of the King Range reach all the way down to the shore, only to be perpetually battered by the merciless Pacific. Don’t walk too close to the bluffs, as rockfall was nearly constant. As the bluffs erode, entire trees simply fall into the ocean; there are a few teetering specimens that I am confident will not be there the next time we return.

At Big Flat, we meandered over to check out the legendary Big Flat House. The house (and its own airplane runway) was built in the 70s and, for years, served as an outpost for surfers, who had this stretch of coastline to themselves. Now, the times have changed. The house was rented out by a silent meditation group, and scores of surfers anchor boats offshore during the big winter swell.

Our friend Dan, an Arcana local and cowboy bush plane pilot, was delivering supplies that day and offered to bring us some beer. We were strolling along the runway, unsure if it was even a runway, when we were startled by Dan careening through the air above us; we were in the way, and he had to abort his landing. He circled around Big Flat for a bonus lap and landed his bird in perfect style, brushing off the stiff wind like a top gun fighter. The plane was packed to the literal brim with the personal belongings of the Yoga Cult; apparently, their silent meditations had not yet led them to renounce their possessions and adopt the minimalist lifestyle of true Buddhist monks.

Dan unfurled himself from the cockpit with a radiant smile and hair permanently blown back from 50-some-odd years of that eternal California breeze. We spoke with Dan for a bit, then watched him take to the skies, eager to catch kitefoil surf sesh with his buddies. We retreated with a bag of ice-cold Sierra Nevada Hazy Little Things to the traditional Big Flat campsite, truly a Ritz-Carlton in the league of campsites.

Watching that California glow settle over the coast as the sun sets low is a priceless experience. Contrary to the previous day, there was little wind at Big Flat. The creek empties into a nice swimming hole just down from the tent sites. Our tent site was full of old driftwood furniture; most notably, there was a massive whalebone the size of our backpacks.

We set up our tent and blanket and watched the sun go down while sipping IPAs. We cooked a decadent amount of Spanish rice and Tasty Bite Indian food packets. Sleep came swiftly and intensely. It was quiet, with the waves at a more manageable decibel from this distance.

Day 3 - Big Flat to Punta Gorda and Back

The next day, we rose early and launched, hoping to cover as much of the rest of the Lost Coast as we could, free from the burden of our packs. The route’s north side, which most people do the first two days, is indeed much less strenuous than south of Big Flat. Much of the hiking is on hard-packed trails on the bluffs above the beach. As a result, we were able to cover 22 miles (36 km) in a day and were limited only by the tides at the Cooskie Creek impassable zone.

Watch out for poison oak in this section; one trail segment is completely covered, and I was forced to walk through it wearing shorts. I went into the icy ocean and scrubbed off with saltwater and sand to remove the oils. Even if the coast weren’t rocky and violent, swimming would be almost impossible on account of the water temperature—such a contrast to the warm air. I only went in up to my thighs, and I think you would be hypothermic within a few minutes in these waters.

The impassable zone between the Punta Gorda lighthouse and Randall Creek is more serious. A few chokepoints, like right next to Randall Creek, fill in fast during a rising tide. Reaching the lighthouse would have required six more miles (10 km) round-trip. Anna and I felt like we could have made it, but we didn’t have enough time to return with the tide coming in. The best sea lion and elephant seal watching is around the Punta Gorda Lighthouse; we were told that it was basically guaranteed to see at least a few sea lions basking on the rocks. We were disappointed to miss this aspect of the trip.

Returning to Big Flat, we stopped for lunch and a swim in Randall Creek. We also stopped at Kinsey Creek, which has a lovely campsite. By the time we reached Big Flat, it was after 6 o’clock, and we were exhausted. It was maybe better that we didn’t do those extra six miles.

We sat on our blanket and sipped on IPAs. We swam in the creek. The warm and calm weather featured not a trace of a breeze. It was the best out of our three nights on the Lost Coast. The glow settled upon the campsite like a hyperbole of Hollywood.

After a characteristically massive dinner, we settled into our cozy sleeping bags as the cool air descended upon Big Flat. It was the best night of sleep I’ve had in a long time.

Day 4 - Big Flat to Shelter Cove

We awoke the following day just shy of 9 a.m. Nobody remained at camp; they had all left hours ago, like the responsible adults they are. But there was plenty of time with the tide, and we had no reason to rush out.

We hitched up our packs and began our 8-mile trek back to civilization. It was sad to say goodbye to Big Flat.

The hike out was largely uneventful, except for the raft of elephant seals resting on rocks toward the end of the impassable zone. We were so excited to finally see some, as we were sure that we’d missed out by not making it to Punta Gorda the day before. An enormous male and about a dozen females and juveniles comprised the group. There was a clear hierarchy. The male was sprawled across the most prominent rock, free from the interruptions of a rising tide. Meanwhile, the juveniles and females were relegated to the smaller rocks, and the ocean’s chop constantly sloshed them into the water.

After watching for a while at a respectable distance from shore, we moved past our newfound friends and toward the finish line. I started to see why people complained about this last stretch. It is a bit of a slog when you’re tired. It’s over quickly, though; we rolled up to Black Sands Beach about five hours after departing Big Flat.

In Conclusion

The Lost Coast is an almighty beautiful region that hikers should savor. Between swimming, wildlife viewing, and exploring the canyons along the various creeks, there’s much more to be experienced than just walking. If the tides allow, a sleep-in and a leisurely morning at camp can’t be beat.

Even with the tides, most people could feasibly do this hike in two days, but it’s best to take it slow and commit to just a half-day hiking per day. This will equate to about four days and three nights on the trail, as we did. One-way, that’s an average of six miles (10 km) or about four hours of hiking each day.

We got lucky with the perfect conditions, and I’m grateful. The weather isn’t always so kind on this coast. Suffice it to say, I won’t forget this trip anytime soon!