Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, about halfway between Norway and the North Pole. The islands, part of the Kingdom of Norway, are known for their rugged and dramatic mountains. There are over 1258 named peaks across the island chain, of which Newtontoppen (1,712 m/5,620 ft) is the tallest and the most prominent.

Svalbard is a group of islands in the Arctic Ocean about 800 km north of mainland Norway. Nine major islands comprise Svalbard, of which Spitsbergen is the largest island. Nordaustlandet, Barentsøya, Edgeøya, Barentsøya, Prins Karls Foreland, Kvitøya, Kong Karls Land, Bjørn Island, and Hopen are the other major islands of the archipelago.

The total land area of Svalbard is approximately 61,000 square kilometers (23,561 square miles), and over 1250 named peaks rise from the islands. When the Dutch explorer William Barentsz discovered the archipelago in 1596, he called it Spitsbergen, which translates roughly as “pointy mountain” in Dutch.

An interesting note is that Svalbard is further north than Greenland's northerly settlement. However, due to the Gulf Stream, the waters around the south and west of Svalbard are relatively ice-free, and an ideal way to view Svalbard is via a small expedition vessel.

Rugged mountains, deep fjords, and glaciers, shaped by millions of years of geological processes, characterize Svalbard’s landscape. Seven national parks, twenty-nine protected areas, fifteen bird sanctuaries, and six nature reserves encompass over 60% of the landmass.

The national parks are Forlandet National Park, Indre Wijdefjorden National Park, Van Mijenfjorden National Park, Nordre Isfjorden Land National Park, Nordvest-Spitsbergen National Park, Sassen-Bünsow Land National Park, and Sør-Spitsbergen National Park. Nordaust-Svalbard and Søraust-Svalbard nature reserves are both more extensive than any of the national parks.

Most of Svalbard’s mountains rise from the island of Spitsbergen. Newtontoppen, the archipelago's tallest peak, rises to 1,713 meters (5,620 feet). Other notable peaks include Perriertoppen, Nordenskiöld Fjellet, and Synshovden.

Except for the meteorological outposts on Bjørnøya and Hopen, all the archipelago’s settlements are on Spitsbergen. Svalbard is home to the four northernmost settlements in the world: Longyearbyen, Ny-Ålesund, Pyramiden, and Barentsburg. Longyearbyen is the largest settlement, the governor's seat, and the only incorporated town in Svalbard.

Svalbard is above the Arctic Circle and so far north that the sun doesn’t set from April 19th to August 23rd. However, the flip side of a four-month-long day is that the sun will set one evening in mid-November the sun will set and won’t rise again until near the end of January.

The Svalbard Airport, near Longyearbyen, is the only airport offering air transport to the archipelago. It is also the northernmost airport in the world with scheduled public flights. Once on the archipelago, Longyearbyen, Barentsburg, and Ny-Ålesund have road networks; however, they are independent and not connected.

Off-road motorized travel on bare ground is prohibited, but snowmobiles are used extensively in winter. During the summer, the best option for travel is by ship, and the major ports around Svalbard, such as those at Barentsburg and Pyramiden, are open year-round.

Millions of years of tectonic processes created Svalbard's mountains. For the past 500 million years, the intricate interaction between plate tectonics, volcanic activity, and glaciers gave rise to Svalbard's geology.

Some of Svalbard’s deepest and most ancient rocks were part of an enormous landmass. These basement rocks of Svalbard were present 410 million years ago when the Caledonian orogeny ended.

The Caledonian orogeny occurred during the Silurian period and is responsible for forming the Caledonian mountain chain. The Caledonian Mountains reach from Svalbard, through Scandinavia to Scotland, and toward the Appalachian Mountains in North America. Greenland’s eastern coast encompasses the counterpart to the Caledonian Mountains.

During the Caledonian orogeny, the mountains were uplifted, and many basement rock layers came to the surface. The basement layer consists mainly of metamorphic rocks such as granite, gneiss, crystalline schist, quartzite, and marble. The mountains also contain igneous rocks, which intruded the upper crust during the orogeny. Newtontoppen, the tallest mountain on Svalbard, is primarily granite.

Some of the younger basement rocks never subsided deeply and therefore were not metamorphosed, and they retain their original characteristics as sedimentary and volcanic rocks.

Following the Caledonian orogeny for about 50 million years, the eroded materials from the formation of the mountains were deposited in layers several kilometers thick upon river plains and in the ocean. The greenish-grey and red sandstone in northern Spitsbergen in Andrée Land formed from these terrestrial deposits.

For the following 100 million years, tectonic action would cause Svalbard to rise and fall in the ocean, creating distinct layers of fossil-rich sandstone and dolomites mixed with layers of gypsum and anhydrite. These layers were deposited along the continental shelf as the Caledonian mountains eroded.

Pangea was forming at the end of the Paleozoic, and Svalbard was locked within the landmass between modern northern Europe, Greenland, and North America. During the Cretaceous, Svalbard was at ground zero for the rift that cut through Pangea and began to form the Atlantic Ocean.

Large parts of eastern and central Svalbard are home to the Mesozoic sandstones and shales created from the accumulation of sand, mud, and gravel. At the time, dinosaurs such as Iguanodons stalked the terrestrial earth, and plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs hunted in the nearby oceans.

Rift systems formed from the southern to the northern hemisphere across Pangea, where molten rock intruded the fissures of the Earth’s rending crust. These intrusions form an igneous rock called dolerite, seen across Svalbard. The intrusions are mainly in layer-parallel dikes, often forming mountain plateaus, ridges, and islands. Kong Karls Land has lava rocks as evidence from that time.

Following the Mesozoic, the rift system expanded the Atlantic Ocean, slowly separating Svalbard and northwestern Europe from northeast Greenland along an enormous fault line. During this process, between 60 and 40 million years ago, part of Spitsbergen folded to form the mountain chains along the island's west side and archipelago.

However, the Earth’s forces hadn’t finished forming Svalbard; after the mountains formed, the landmass subsided into a basin where debris accumulated. During this time, conditions were favorable for coal formation, which would later become the primary economic driver of the archipelago.

In the middle of the Tertiary, a new phase of volcanic activity affected the North Atlantic. In Andrée Land, the Tertiary lava flows still exist as resistant basalt lava mountains and plateaus. Several sizable basalt plateaus, including Vestfjella and Fuglebergsletta, evolved due to this volcanic activity.

When the volcanoes erupted, the valleys and lowlands filled with lava. Erosion then affected the softer sandstone and shale, essentially inverting the ancient topography of the islands, where the hard basalts now form the mountain peaks, and sandstone eroded to form valleys and lowlands.

During the Pleistocene, thick ice often covered Svalbard. Naturally, the islands have been subject to the major glacial maximums of the past 300,000 years. However, some mountain peaks and coastal areas may have avoided being covered by ice during at least some glacial periods.

During the Pleistocene, the volcanoes were still active in the region. Sverrefjellet is the most prominent volcano. Located in north-western Spitsbergen, it is only 100,000 to 250,000 years old. The thermal springs near Bockfjorden attest to relatively high levels of volcanic activity that are still present in the region.

About 10,000 years ago, the ice melted from Svalbard over 2,000 to 3,000 years. During that time, the climate was a little warmer, and the ecology was similar to that of northern Norway; however, Svalbard has since cooled, and the island's arctic ecology is a testament to the cool climate.

Its location above the Arctic Circle significantly impacts the ecology of Svalbard. Despite its location, Svalbard has a relatively mild climate with an average winter temperature of -14 C and an average summer temperature of 6 C. However, the archipelago is still among the world’s harshest environments, and the island’s plant and animal life is undoubtedly hardy.

Tundra dominates the lowlands of Svalbard, which are characterized by the presence of mosses, lichens, and small flowering plants. There are no trees in Svalbard, as the long, dark winters prevent their growth. Shrubs may grow to about 10 cm (4 in) in height.

Despite its apparent hostility and the fact that only 10% of Svalbard’s landmass has vegetation, there are 164 plant species documented throughout the archipelago. These hardy plants can withstand extreme cold, strong winds, and permafrost in this Arctic climate. Several small mammals, such as lemmings, voles, and Arctic foxes, inhabit the lowlands, relying on the sparse vegetation for their sustenance.

The vegetation becomes sparser, giving way to rocky terrain and scree slopes as you move higher into the mountains. However, despite the harsh conditions, pockets of vegetation containing Arctic willow and Arctic poppy still survive in what appears to be an incredibly hostile environment.

The waters surrounding Svalbard are rich in marine life, including several species of fish, twelve species of whales, five species of seals, and walruses. Walruses were hunted to near extinction; however, with recent protections, Svalbard supports an estimated population of 3000 walruses.

The most iconic and well-known species of Svalbard is the polar bear, found throughout the archipelago. Polar bears have adapted to the Arctic environment, with thick fur and a layer of blubber that insulates them from the cold. Indeed, Svalbard is one of the best locations in the world to view polar bears in their natural habitat, and polar bears outnumber the human inhabitants of the islands.

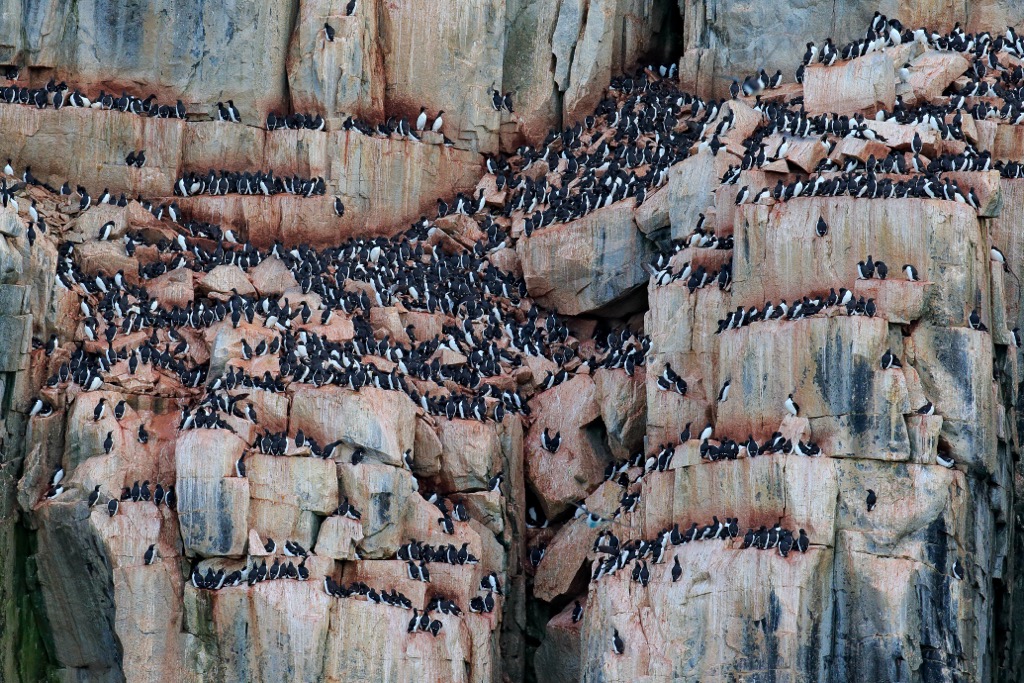

Several bird species, including Arctic terns, puffins, and guillemots, migrate to Svalbard during the summer. A single tern can fly 40,000 km (25,000 miles) a year from the Arctic to Antarctica and back again. The Svalbard rock ptarmigan is the only bird that doesn’t leave Svalbard during the winter.

While searching for the Northeast passage to China, Dutch mariner Willem Barentz spotted Bjørnøya on June 10, 1596, and the northwestern tip of Spitsbergen on June 17. His sighting of the islands is the first undisputed discovery of the archipelago, and cartographers of the day quickly included the maps produced by the expedition.

There is nothing on the archipelago to confirm that it was inhabited prior to the discovery by Barentz; however, several alternate timelines exist. Some unsupported evidence suggests at least a visit to the islands by stone age people; however, archeologists are generally unconvinced by this theory.

During the nineteenth century, Norwegian historians proposed Norse seamen had encountered Svalbard as early as 1194. The idea is based on annals that say Svalbarði was four days sailing from Iceland; however, aside from taking the modern name of the archipelago from the ancient tales, there is no evidence to support this theory.

Russian historians have proposed that Russian Pomors visited the islands as early as the fifteenth century. Like many other attempts, Russian attempts to study the discovery of the islands appear to be more for patriotic clout than evidence-based science.

However, based on the Cantino Planisphere, an early map that records Portuguese discoveries in the New World, an archipelago closely resembles Svalbard. If correct, Portuguese sailors may have discovered Svalbard nearly 100 years earlier than the Dutch.

Various groups have inhabited the islands for centuries, starting with seasonal whaling camps that became year-round settlements. Whaling lasted in Spitsbergen from the 1630s until the 1820s, when Dutch and British whalers moved elsewhere in the Arctic.

By the late seventeenth century, the Russians arrived and subsisted from hunting animals such as polar bears and foxes. Norwegian walrus hunting began in the 1790s. The first proper Norwegian citizens to reach the islands were a group of Coast Sámi people hired for a Russian expedition in 1795.

Shortly before the turn of the nineteenth century, Svalbard had become a destination for Arctic tourism, which ironically helped discover coal deposits that continue to be mined. Through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most of the inhabitants of Svalbard worked for one of the major companies.

With the establishment of the Svalbard Treaty in 1920, Svalbard came under full Norwegian authority; however, the treaty's signatories received many rights within Svalbard. Said countries may operate commercially within the archipelago without discrimination, workers do not need work permits or visas to reside on the islands, and foreign governments and institutions can build research stations.

Svalbard has become an important center for scientific research, and several countries have established research stations on the archipelago. This research focuses on a range of topics. However, most research is in glaciology, geology, biology, and climate change.

Norway has allowed representatives worldwide to work, live, and study in Svalbard, creating an international community on its frozen shores. Further international cooperation in Svalbard is exhibited at the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, designed to preserve the world's crop diversity in the event of a global catastrophe. The vault houses seeds from around the world; however, the facility is heavily fortified, and foreign dignitaries from donating countries are not permitted to tour the facility.

Mining in Svalbard is still the largest industry; however, tourism, education, and research are also important. Cruises and tours are offered to visitors to sail around the archipelago, making stops to view northern wildlife, calving glaciers, and the incredible arctic mountain landscape.

The islands currently have a population of under 3,000, and polar bears outnumber people. Svalbard has a relaxed stance on immigration, and anybody can come to work on the islands. The inhabitants of Svalbard currently represent 50 nationalities.

Svalbard is a remote archipelago above the Arctic Circle, with few tourist services. Most tourists explore the archipelago by boat during the summer. During the winter, visitors can travel by snowmobile or dogsled.

Stunning views, rugged wilderness, abundant wildlife, and amazing adventures await those willing to travel to Svalbard. About 65% of Svalbard’s landmass is within a protected area, and the following are some of the most significant natural attractions.

The newly-established Van Mijenfjorden National Park is on the eastern coast of Spitsbergen. The new park includes the former Nordenskiöld Land National Park, extending to the border Sør-Spitsbergen National Park.

Reindalen, Svalbard’s largest ice-free valley, is one of the park's most prominent features. Visitors can see moraines, rock glaciers, pingos, and avalanche features here. Furthermore, the valley's lower part is a wetland with lush vegetation, which is rare in Svalbard.

The park is home to Arctic foxes, reindeer, polar bears, and many birds that breed and nest within its boundaries, such as common eider ducks, barnacle geese, and pink-footed geese. Access to the park is regulated to help protect the fragile environment.

Forlandet National Park is located off the west coast of Spitsbergen and encompasses the island of Prins Karl’s Forland. The park covers an area of approximately 660 square kilometers (255 square miles) and features majestic peaks, cliffs, and stunning shorelines.

Visitors can arrive by boat, explore the coast, and hike among the park's mountains. Forlandet National Park is home to a diverse array of wildlife, including walruses, polar bears, and several species of seabirds. Indeed, the park has six bird sanctuaries, making bird-watching a perfect activity while visiting.

Pyramiden is an abandoned Russian mining town in central Svalbard at the foot of Billefjorden. The community once had over 1,000 inhabitants when the mine was operational. When the mine closed in 1998, the last resident moved away the same year. The town remained uninhabited and essentially untouched until 2007.

The town is now a tourist destination that gives a unique glimpse into the Soviet era. It once touted the northernmost statue of Lenin and the northernmost swimming pool. The town is now inhabited by several people operating the hotel and guiding tours of the town and its old buildings.

While there are no plans to renovate and reopen the whole town, there is a museum, post office, and a souvenir shop in addition to the hotel. There is even a functioning movie theater where visitors can request to view one of over a thousand Soviet films preserved onsite.

Guests can access accommodations and services while visiting Svalbard in a couple of communities. When visiting the archipelago, it is essential to note that accommodation is limited and should be booked well in advance.

While in Svalbard, visitors will have the opportunity to visit local museums and local wilderness attractions. While most communities have some form of guesthouse, accommodations are limited and must be booked well in advance. The following are the communities with visitor services and accommodations.

Longyearbyen is the largest settlement in Svalbard and the only incorporated town on the archipelago. It is on the west coast of the main island, Spitsbergen, and is the administrative center of Svalbard. It’s home to several research institutions, including the University Centre in Svalbard.

With a population of around 2,300 people, Longyearbyen is the central hub for transportation and services in the archipelago, including a port and a public airport. Longyearbyen is also home to most visitor and tourist services in the archipelago.

While visiting Longyearbyen, there are many beautiful spots for hiking and adventuring.

Barentsburg was established in 1910 by a Dutch company as a mining settlement but was later taken over by the Soviet Union in the 1930s. The settlement is located on the west coast of Spitsbergen and is home to about 400 people.

The town is the last remaining Russian settlement on Svalbard, and it is a popular tourist destination for visitors to the archipelago. Tourists come to explore the town’s Soviet-era architecture and learn about its history.

While in Barentsburg, tourists may enjoy visiting Grønfjord, a beautiful fjord located just outside town. There are several trails from which hikers can view a wide range of wildlife, such as seals, walruses, and polar bears, or explore the remains of an old Soviet-era mining settlement in the fjord. Another place to visit is the scenic valley of Tverdalen, which has hiking trails to the nearby mountains and incredible views of the surrounding glaciers.

Explore Svalbard with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.