Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Santa Barbara County is the jewel of California’s Central Coast, one of the great destinations of America. The county is defined by the city of Santa Barbara and the Santa Ynez Mountains that tower above it. However, the county line also includes the Channel Islands, perched off the coast of Santa Barbara, as well as the San Rafael Mountains, located north of the Ynez. California’s coastal Mediterranean climate offers brilliant sunshine nearly every day, though many days also feature morning fog coming off the Pacific Ocean. Hiking, mountain biking, road cycling, and paragliding are just a few ways to recreate in the Santa Ynez. Off the coast, the Channel Islands National Park is famous for hiking and diving. In total, there are 111 named mountains in Santa Barbara County. Big Pine Mountain, in the San Rafael Mountains, is the highest point. The most prominent mountain is Devil's Peak, on the Channel Islands.

Santa Barbara County covers approximately 3,789 square miles (9,813 sq. km). The Pacific Ocean borders it to the west and south, San Luis Obispo County to the north, Ventura County to the east, and Kern County to the northeast. The Santa Ynez Mountains run parallel to the coastline, dividing the Mediterranean coast from the inland desert valleys.

One of Santa Barbara’s defining features is its location along a southern-facing expanse of California’s coastline. The town gets an extraordinary amount of sun throughout the day and also fewer weather systems off the Pacific. As a result, the climate is generally hotter and drier than other locales along the mid-coast. Coming from the north, Santa Barbara is really the first place in California where you can swim in summer for an extended time without a wetsuit. The water temperatures reach around 62℉ (17℃), which, though chilly, is far more manageable than Santa Cruz and San Francisco.

The U.S. Department of the Interior designates the Santa Ynez Mountains within Los Padres National Forest and the Channel Islands as a national park. Whereas it’s free to visit and recreate in national forests, national parks generally require the purchase of a pass, as well as stricter regulations regarding camping and recreation.

Santa Barbara County's Pacific coastline comprises mostly rugged cliffs and sandy beaches. Inland, the fertile Santa Ynez and Lompoc Valleys support many farms, including several beloved vineyards.

Despite its mountainous character, Santa Barbara County is a significant population center, with about 450,000 residents as of 2025. Although the county seat and most famous city is Santa Barbara, Santa Maria is the largest city. Other towns include Goleta, a suburb of Santa Barbara, and Montecito, home to the rich and famous.

Like the rest of California’s Coast Range, Santa Barbara County’s geology is shaped by the intense tectonic activity along the boundary of the Pacific Plate and North American Plate.

The Santa Ynez and San Rafael Mountains were formed about 20 million years ago due to compressional forces along the Santa Ynez and San Andreas Faults. These mountains are composed largely of sandstone, shale, and limestone, deposited in ancient seabeds before being uplifted and folded. Meanwhile, seasonal streams draining toward the ocean have carved the mountains' deep canyons.

Both ranges are also part of the Transverse Ranges, a unique geological province in California where the mountains run east-west—rather than the typical north-south orientation—caused by the oblique motion of the Pacific Plate over millions of years.

The Santa Barbara Channel Basin is also a product of tectonic activity, with significant faulting and folding contributing to the area's petroleum reservoirs. People often think that Santa Barbara’s offshore oil rigs are responsible for the chunks of tar on the beaches, but they are actually natural oil seeps.

Santa Barbara County’s ecological richness is one of the key drivers of tourism, especially on the Channel Islands. Because the county contains both the mainland (Santa Ynez Mountains) and the Channel Islands, it’s one of the most biodiverse counties in the U.S.

The climate of Santa Barbara is, well…perfect. At least for human habitation.

Most years, the sun shines nearly year-round, with only a few days of rain during the winter months. There are plenty of foggy days, especially during June, a phenomenon known as “June gloom,” though fog is a year-round phenomenon. Hiking up into the Santa Ynez Mountains is a great way to escape the coastal fog. Gazing upon a sea of clouds from the mountains, the peace and solitude become palpable.

June Gloom turns to “July fry” as things begin to heat up for summer. While the rest of the country is cooling off and buttoning up for winter, October and November can remain quite warm in Santa Barbara.

Rainfall averages around 16 inches per year (40 cm), though there is a lot of variability; the last 10 years have seen as much as 40 inches (100 cm) and as little as 5 inches (12.5 cm).

The Santa Ynez Mountains are home to what would be called a “Mediterranean” climate by the casual observer. However, Santa Barbara is also far south enough to have a desert influence. In the Santa Ynez, you won’t find the fabulous biodiversity of the Big Sur area, just a couple of hundred miles to the north. Instead, a dry chaparral ecosystem features species like scrub oak and manzanita, interspersed with California’s famous golden grasses (they turn green in the winter, assuming adequate rainfall).

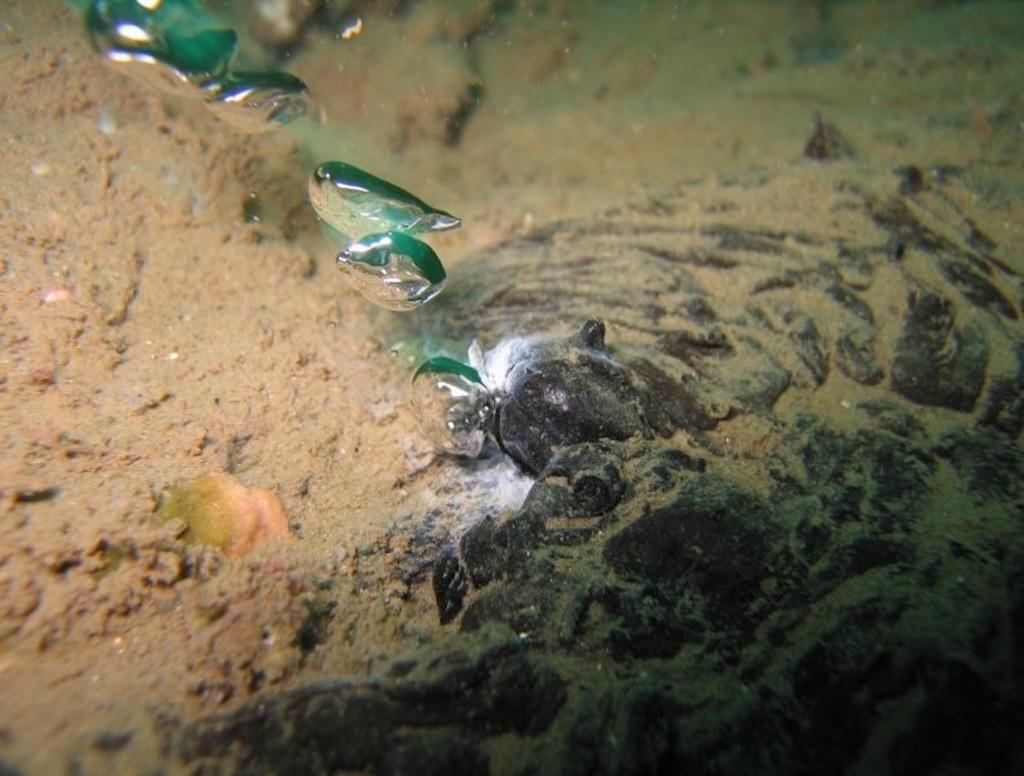

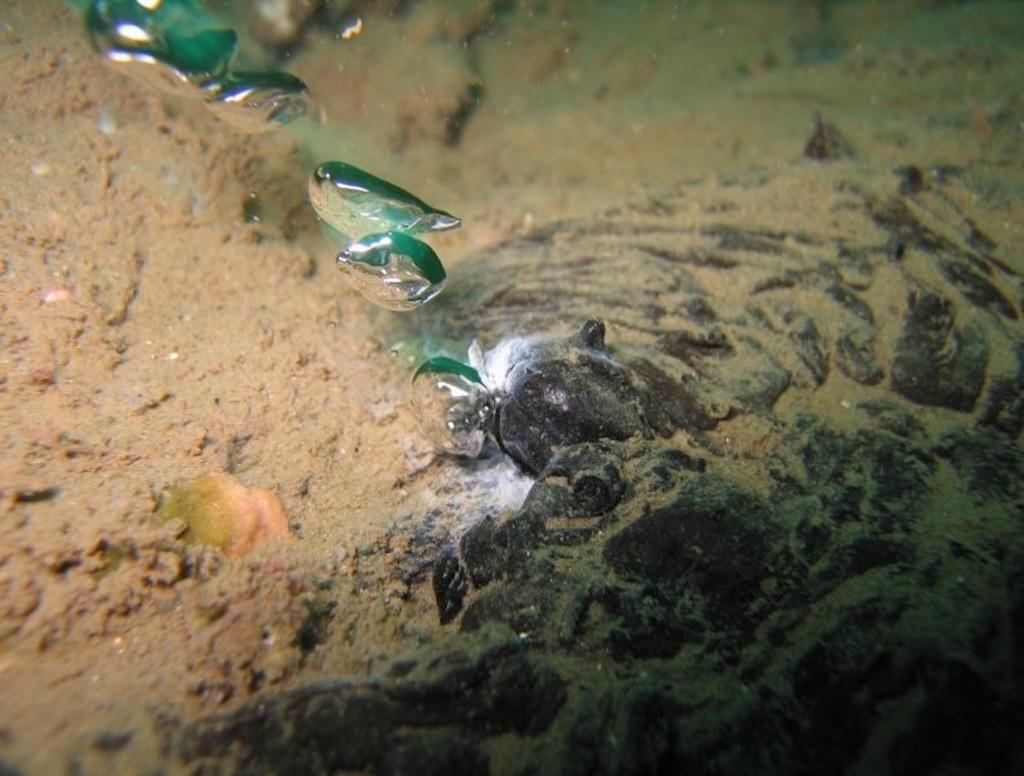

Santa Barbara County’s most magical fauna is found not on the mainland but in the ocean and on the Channel Islands. Dolphins and whales are a common sight, both on the beaches in Santa Barbara and the islands. Six of the eight Channel Islands are also home to the endemic island fox, which has evolved in isolation on the islands.

Climate change isn’t a hypothetical in California; it’s been a reality for decades. The most visible sign of climate change in Santa Barbara County—and across California—is the burn scars that are increasingly ubiquitous in the backcountry. Of course, California is no stranger to forest fire, and the chaparral zones along the mid-coast are fire resilient; some species even depend on regular fires to germinate.

However, the ecosystem's composition is changing as fires get hotter and more frequent. You’ll notice this in the Santa Ynez, where the burnt tree shells are commonplace throughout the high ridges, where winds have whipped up unsurvivable fires. Forest vegetation, like trees, still survives in the gullies and canyons where water is more accessible. However, the exposed ridges are no longer a suitable climate for trees, with only the ghosts remaining.

Another less visible effect of warming oceans is the slow but steady rise in sea level. Experts expect sea level to rise at least 3 feet (~1 meter) by the end of the century, which will spell doom for about 40% of Santa Barbara’s public beach access. Some will survive longer than others, but rising seas will eventually spell doom for all of California’s beaches.

Lastly, the Channel Islands are a national marine sanctuary due to the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the California coastline. Here, a phenomenon of coastal upwelling brings cold water to the surface, fostering California’s famous coastal biodiversity. It’s unclear what effect a warming climate will have on this ecosystem—there are many variables, and proper modeling is complex—but these ecosystems will likely change in the future.

Humans have inhabited the land that comprises Santa Barbara County for about 12,000 years. The first, and by far the longest, residents have been Native Americans, most recently the Chumash Indians. The Chumash navigated back and forth between the mainland and the Channel Islands in canoes called tomols and developed a complex trade network between organized villages.

Like other native North American Peoples, the Chumash tribe’s idyllic existence ended abruptly in the 18th century. Spaniards had explored the coast as early as 1542, but the Mission Santa Barbara was formally established in 1786. The mission brought a wave of immigration, and the new settlers began establishing large ranches. In the first decades, the Chumash were significantly weakened by a wave of European diseases to which they had no immunity. They also became victims of forced labor and religious conversion.

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821; the new Mexican landowners became known as “Californios.” In 1848, the U.S. annexed California from Mexico, and Santa Barbara became one of 27 counties in 1850 when California was granted statehood. The transfer of power was devastating to the Californios, as the U.S. effectively stole most of their land, just as the Californios had done themselves to the Chumash.

The Santa Barbara County coast has long been recognized as a health and wellness center, attracting alternative lifestyles since before alternative lifestyles were much of a thing.

Notable industries are oil and agriculture. Inland, the county is still an agricultural empire, with hubs like Santa Maria and Santa Ynez. Oil was the coastal industry, beginning around 1895. It was no secret there was oil in the Santa Barbara Channel, as the beaches are full of naturally occurring tar balls seeping up from the seafloor. The Santa Barbara Oil Spill of 1969 marked the decline of the industry.

Now, just a few off-shore derricks remain, with only about 10 million barrels of oil reserves left, compared to the 250 million extracted. Besides, the value of coastal real estate has far outpriced the value of any remaining oil. If there was a (not-in-my-back-yard, or NIMBY) hub of the world, Santa Barbara could be a serious contender. NIMBY environmentalism has succeeded in subduing the oil industry, but it has also blockaded solar and wind projects throughout California.

Today, the inland portions of Santa Barbara County are agricultural centers. Santa Maria is the county’s largest city, but there isn’t much reason to visit as a tourist.

Meanwhile, coastal Santa Barbara County is mainly a wealthy enclave, an escape for Los Angeles elites and other well-funded lifestyle seekers. Make no mistake, the outdoor recreation is top-notch, so if you can afford it, Santa Barbara is the spot. Santa Barbara is a hub for all the outdoor sports we love here at PeakVisor, like surfing, hiking, mountain biking, paragliding, trail running, ocean swimming, and more.

Santa Barbara County is massive and covers several different hiking regions. There are a lifetime of hikes on the Channel Islands and in the Santa Ynez. Here are a few of the most quintessential adventures in Santa Barbara County:

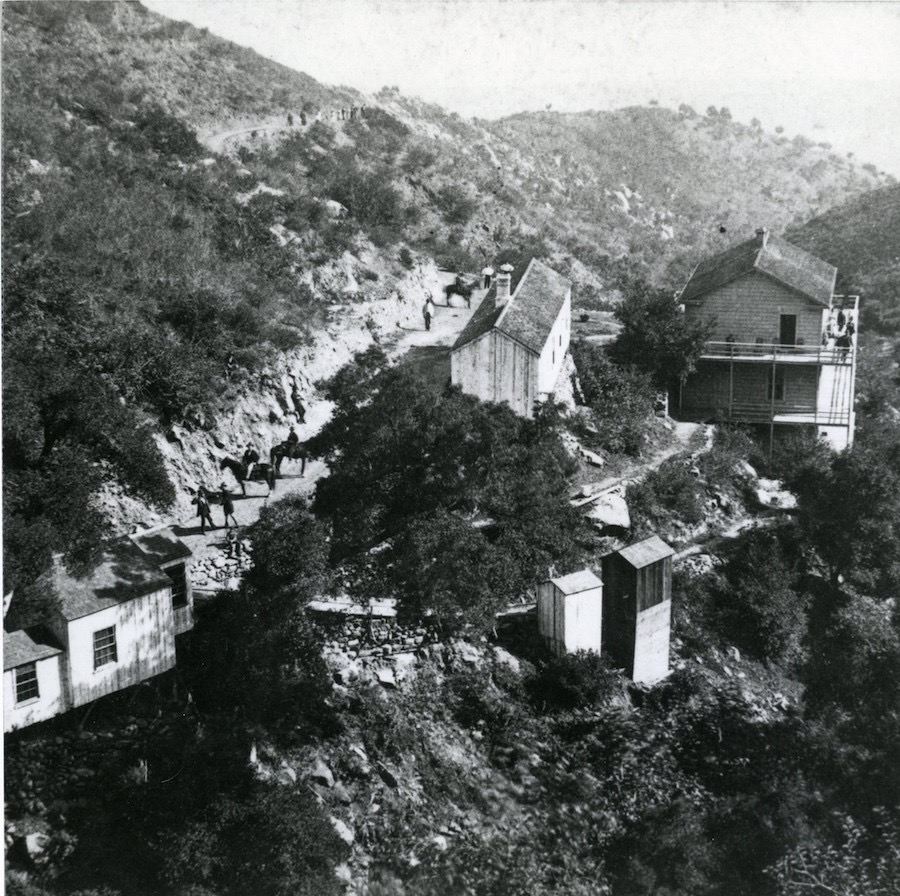

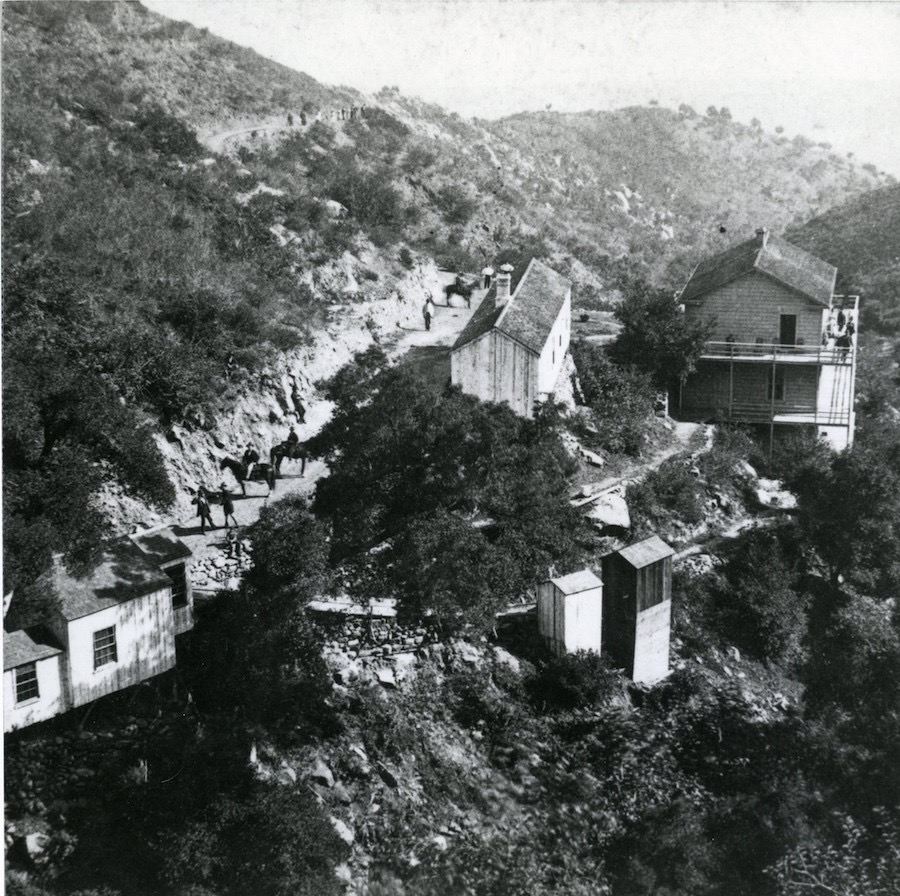

Montecito Hot Springs is sacred ground. For millennia, it was a holy place for the Chumash, who would rejuvenate in the mineral-rich waters. In the 1850s, the white man discovered the springs' healing powers and built a resort. By 1887, the resort proved unprofitable, and the infrastructure gradually fell into abandon. Fortunately, the springs have been protected and are now public access.

The 2.5 mile (4 km) Hot Springs Canyon Trail starts on East Mountain Drive in Montecito, slightly east of Santa Barbara. There’s a small parking lot at the base. The trail winds up a mostly dry riverbed, gaining about 800 feet (250 meters) of elevation to get to the springs. Just before reaching the springs, you’ll pass the remnants of the old resort perched up on the hill above the riverbed.

The springs feature several pools, with the pools closer to the source being hotter. Water temperatures can reach 122℉ (50℃), though the water cools as you move away from the source. Just so it's not a surprise, most people here will be naked.

Cathedral Peak is another local Santa Barbara trail that heads up into the Santa Ynez front range. The trail starts on Tunnel Road in the hills above downtown. There’s street parking at the base.

Now, the challenges begin. The trail from the Tunnel trailhead is about 8 km out and back, with 2,400 feet (725 m) of elevation gain. However, hikers must be prepared for grade 2 rock scrambling and plenty of route finding. The southern aspect and lack of shade mean this can be a boiling-hot adventure, even in winter. Bring plenty of water. Unprepared parties have called search and rescue more times than you can count on this trail, but prepared hikers will cherish Cathedral Peak as the best route in Santa Barbara.

Because the ridge is dry and rocky, the trail can be ill-defined. It’s the perfect opportunity to fire up the PeakVisor App, available for iOS and Android.

The Channel Islands are a treasure trove of hikes; keen hikers could spend weeks exploring the different islands. One notable hike is El Montañon Peak on Santa Cruz Island. The hike starts near the Lower Scorpion Campground, at Santa Cruz Island’s main ferry anchorage. The hike follows a relatively gentle ridgeline up to El Montañon Peak, gaining about 2000 ft (600 m) of elevation along the way. The out-and-back route is around 9 miles (14.2 km).

A bonus is to take Smuggler Road down to Smuggler’s Cove. If you choose to do this, it’s a 6.2-mile (10 km) round-trip detour, or you can loop it with the Montañon Trail using the Montañon Ridge Trail. However, I’m unsure of the ridge trail’s condition, so do additional research if you want to attempt the loop.

This is an easy one, perfect for families. The Nojoqui Falls trail is only .9 miles (1.4 km) out and back, with about 200 feet (60 meters) of elevation gain. The exquisite falls feature a 100-foot drop over moss-covered rocks. There’s free parking at the trailhead, which is just off Highway 101 on Alisal Rd., 15 minutes from the town of Solvang.

Santa Barbara city is the namesake and most beautiful population center in the county, if not the world. Looking down at Santa Barbara from the mountains offers a view that rivals places like Italy and Greece. If you’re up there during sunset, it becomes genuinely world-class.

Though it’s a small city of about 100,000, you won’t run out of things to do. Check out any number of trails in the Los Padres National Forest above the city. The close-knit mountain biking community has maintained several exceptional trails, and night riding with lights is common to avoid the sun’s heat during the day. Surfers can check out Leadbetter Beach, while East Beach is the spot to bask in the sun or drop in on a beach volleyball game.

Because of its southern exposure—Santa Barbara sits on a rare south-facing stretch of California coastline—the ocean waters are comfortable for swimming during summer. For those who don’t know, California waters are notoriously icy due to the cold coastal upwelling.

The city itself is straight out of the “Hotel California” album cover, with its Spanish colonial revival architecture (the album cover is actually a photo of the Beverly Hills Hotel). California is famous for its afternoon light, the glow that appears for an hour or so around sundown. Combined with scenes of palm trees and white buildings, the pink glow makes you feel like you’ve been transported into a movie.

Montecito has a stuffy reputation as home to film industry bigwigs and Fortune 500 executives. Nevertheless, it’s gorgeous and worth exploring. Two of the best trails—the Cold Springs Trail (also great for mountain biking; don’t forget to grab a bell at a local bike shop) and the Hot Springs Canyon Trail—start from Montecito.

Butterfly Beach and Hammonds Beach are local favorites and are quieter than the East and West beaches in Santa Barbara. Lotusland is a world-renowned botanical garden with exotic plants and landscape design in a former Ganna Walska estate. You can walk around the hilly streets and gaze at the estates, or at least those that aren’t gated off. Despite its exclusivity, Montecito does possess something of a quaint neighborhood vibe.

If you traverse up over the Santa Ynez Mountains, you’ll eventually arrive in the sprawling Santa Ynez Valley, one of the most prominent players in California’s wine industry.

Santa Ynez and Solvang are the population centers of the Santa Ynez Valley. Santa Ynez was established in the 1880s as part of a stagecoach route and still retains an old-west frontier look that is the polar opposite of Santa Barbara. Meanwhile, Solvang is a re-imagined Danish village, founded in 1911 by Danish immigrants looking to recreate their home country. The town is complete with windmills and traditional timbered storefronts, in contrast to Santa Ynez’s old-west facades.

Solvang has some interesting shops and architecture, but the main attraction here is the wine. The valley’s Mediterranean climate and rolling hills create ideal conditions for viticulture; dozens of boutique wineries and vineyards produce Pinot Noir, Syrah, Chardonnay, and more. Santa Ynez and Solvang are home to tasting rooms, and peppered throughout the valley are vineyards with options for tours, tastings, and more. Fess Parker Winery & Vineyard, Andrew Murray Vineyards, Bridlewood Estate Winery, and Rusack Vineyards are just a few of the most famous vineyards in the region.

Explore Santa Barbara County with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.