Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

The vast domain of Queensland (QLD) is larger than most countries and is Australia’s "Sunshine State." While it's accurate that “sunshine” characterizes much of the weather across this vast region—and the rest of Australia, for that matter—QLD features everything from wet tropical rainforest to hot desert. The mountains range from lush rainforest-covered peaks in the east to the dry, rugged ranges of the interior. QLD’s most prominent mountain system is the Great Dividing Range, which stretches over 3,500 kilometers (2,175 miles) from Victoria through New South Wales and into QLD. In total, there are 3751 named mountains in Queensland; the highest and the most prominent is Bartle Frere South Peak (Ngajanji: Choorechillum) (1,611 m / 5,285 ft).

Queensland, Australia’s second-largest state, covers approximately 1.72 million square kilometers (665,270 sq. miles) in the nation’s northeastern quadrant. It stretches from the tropical regions of Cape York in the north to the subtropical southern border with New South Wales and from the Pacific coastline in the east to the arid interior of the Outback in the west.

The Great Dividing Range is Queensland's (and the Australian continent’s) most significant mountain range. The range spreads over 3,500 kilometers (2,175 miles) from the northernmost point of the Cape York Peninsula down through New South Wales and Victoria. Most of QLD’s ranges are actually subranges of the overarching Great Dividing Range.

The Glass House Mountains are an iconic cluster of volcanic plugs that rise sharply from the surrounding plains. The Gubbi Gubbi people, the Traditional Aboriginal Owners, consider these mountains sacred. They are featured in many Dreamtime stories—essentially the cannon of mythology that Aboriginal people developed to explain the world and its origin.

The Bellenden Ker Range forms the eastern edge of the Atherton Tablelands and features Queensland’s highest peaks, Mount Bartle Frere and Mount Bellenden Ker. The ascent of Bartle Frere is likely Australia’s greatest possible vertical ascent in one go, at over 1,500 vertical meters (5,000 ft) of climbing. The Bellenden Ker is also one of the world’s wettest places; though exact measurements are elusive, rainfall averages an astonishing 8 meters (320 inches) annually.

Much of the East Coast comprises rare and ancient rainforests, like the 180-million-year-old Daintree Forest. National Parks protect much of the remaining rainforests, which are also UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Australia is a proponent of the National Parks system, and QLD is home to many of these federally protected lands. In fact, there are 220 national parks in QLD and more than 1000 protected areas in total. Needless to say, we can’t list all of these, though a few of the most significant mountainous parks include:

For a complete list of protected areas, including national parks, state forests, conservation parks, and more, reference the Queensland Government’s A-Z Parks and Forests listing. You’ll need a National Parks Pass to enter any of the National Parks.

Let’s quickly reference a few of QLD’s demographic markers to paint a picture of just how vast and empty this territory is. About 75% of the population lives in the tiny Southeast QLD (SEQ) sector, and within SEQ, 90% live in the Brisbane, Gold Coast, and Sunshine Coast metro areas. The vast majority of the remaining residents live in small coastal cities like Cairns, Mackay, and Townsville City. Much of the QLD interior is virtually uninhabited, with the population becoming sparser the further west you go.

As you venture from the coast, you delve deeper and deeper into what Australians call the “Outback.” The further west you travel in QLD, the more desolate the landscape becomes, with the westernmost regions comprising hot deserts with only a few hardy scrubs surviving. Most of the parks are within a couple hundred kilometers of the coast.

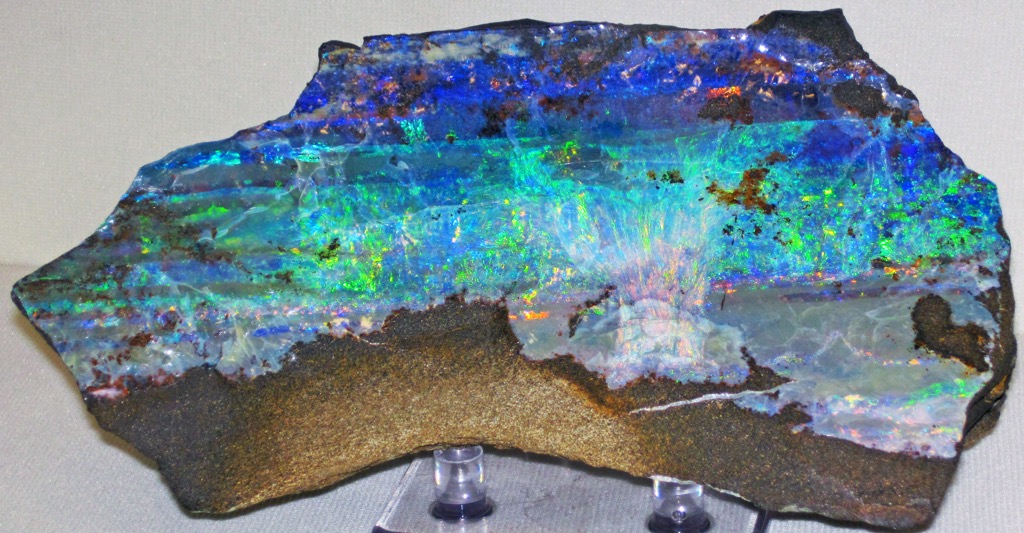

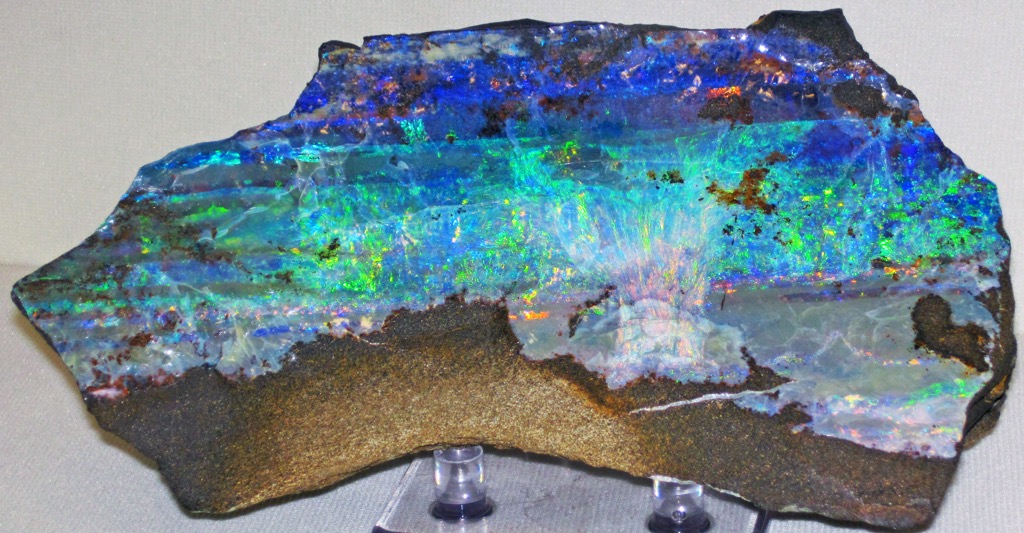

Pressing inland from the Queensland coastline, the landscape feels untouched and ancient. It’s not just a vibe; the foundation of QLD’s geology lies in some of the Earth’s oldest rocks, with formations dating back to the Precambrian era, over 3.5 billion years ago.

The mountains themselves are geologically more recent. The eastern portion of QLD is dominated by the Great Dividing Range, formed through tectonic uplift and volcanic activity during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras, about 250 to 150 million years ago.

More recently, during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods (200 - 50 million years ago), eastern QLD was also home to extensive volcanic activity. The celebrated and sacred Glass House Mountains are the remnants of these ancient volcanic plugs.

Most recently, during the Cenozoic era (beginning 66 million years ago), much of QLD was covered by shallow seas, leading to thick layers of sandstone, shale, and limestone. Though the eastern portions are now desert, the impact of water has continued to shape the Great Dividing Range. Much of the mountainous landscape—which features many gorges and canyons—results from the ongoing erosion.

Queensland’s mountains are abundant, well-protected, and beautiful. But they aren’t staggering in the same way that the Alps or the Himalayas are. You won’t find jagged, snow-covered peaks and cascading glaciers. Nor are the mountains particularly prominent.

What you will find are several of Earth’s most critical ecosystems, some dating back to the early age of dinosaurs. There are many ecologies, from arid deserts to the Great Barrier Reef, but QLD’s mountains are broadly characterized by two: rainforests in the east and eucalyptus forests across the drier inland slopes.

In northeastern QLD, the Wet Tropics, home to the famous Daintree Rainforest—are a glimpse into a world as old as many stars. The forest is a living museum where plants and animals have continuously evolved in a warm, moist environment for hundreds of millions of years (at least 180 million, according to current estimates). Giant strangler figs, prehistoric ferns, and canopy-dwelling epiphytes—plants that grow on the surface of other plants—dominate these jungles.

One of Queensland’s most infamous hikes, the route to the summit of Bartle Frere, traverses from lowland tropical rainforest to rare cloud forest above 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) and is the most immersed you can get in these forests. Though it’s technically south of the core Daintree forest region, the vegetation and biodiversity are comparable.

South and inland, rainforest gives way to eucalyptus woodlands, the quintessential Australian “bush.” The various species of the Eucalyptus genus comprise most of Australia’s forests (75%); these plants are native only to the Australian continent and parts of the Pacific Islands to the north.

Eucalyptus woodlands cover the western side of the Great Dividing Range. Eucalyptus trees require consistent fire to regenerate and are therefore less abundant on the wetter Eastern slopes. The forests are more open, with Eucalyptus’ silver bark and aromatic leaves contributing to the decidedly prehistoric feel.

Though they aren’t nearly as biodiverse, these forests are home to Queensland’s most iconic species. Australia’s most beloved mammal, the Koala, spends its days lounging in eucalyptus branches. You’ll have to get lucky or be extremely observant to spot one of these fellows, though; they stick to the canopy, dozens of meters off the ground. Their numbers are also dwindling due to habitat loss from fires, forestry, agriculture, and development.

Meanwhile, kangaroos and wallabies thrive on the forest floor; you’ll see hundreds if you spend some time in the wilderness, particularly in drier forests with grassy spaces between the trees.

There’s a difference between beneficial burns and devastating wildfires. In recent years, warmer temperatures and drier soil conditions have produced vicious blazes known as crown fires. Rather than clear out the understory, these fires reach above the forest's canopy, killing Eucalypt trees and wildlife and making it difficult for the forest to regenerate. Koala bears, for example, instinctively head for the top of the Eucalypt during a fire and cannot escape if the flames burn higher. It’s one of the reasons their population has decreased to 100 - 500 thousand from an estimated 10 million pre-colonization (95-99% decimated).

Queensland’s human history is a tale stretching through 65,000 years of Aboriginal heritage, followed by the resource extraction and colonial ambition of Western newcomers. Australia is still reconciling its role as the perpetrator of one of the most devastating colonization episodes in history, similar to North America.

Long before Europeans showed up with their thirst for riches, QLD was home to a rich tapestry of Aboriginal cultures, including the Yidinji, Turrbal, and Kabi Kabi peoples. The Torres Strait Islanders are another major group, historically residing on the islands north of the Cape York Peninsula.

Aboriginal people arrived in Australia approximately 65,000 years ago; their closest lineage is ancient Asian peoples. Subsequently, their gene pool diverges.

For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal communities lived in relative harmony with the land, managing its resources through sophisticated practices like controlled burning—the original bushfire management. Like the existence of other indigenous societies, theirs was subsistence-oriented. Resources were relatively abundant, and people worked only a few hours a day, leaving plenty of time for the development of languages (over 500 distinct forms), spirituality, and complex community and familial hierarchies, structures, and laws.

The year 1788 marked the first passage of James Cook (he landed around the Sydney Harbor) and the beginning of the colonization of the Australian continent. Compared to the Americas, colonization was relatively rapid; by the early 19th century, it was reported that an Australian dialect had already evolved from standard British English.

However, colonialism in QLD began a bit later when the Moreton Bay Penal Colony was established in 1824. The colony only lasted 15 years, until 1839, although conditions were atrocious, and many convicts didn’t make it. Brisbane was born out of the remnants of this penal colony when free settlement became permitted in the 1840s.

The next hundred years involved a typical story of European colonization, where resources were gradually depleted, and indigenous people were subjected to forced labor and loss of traditional lands. QLD managed to add another layer of atrocity with their coercion and enslavement of Pacific Islanders.

In the modern-day, PeakVisor readers can be thankful that QLD has matured into a playscape for mountain and nature enthusiasts.

The state was never destined to be populous; even in a world with modern amenities, the tropical climate is difficult to live in, and the western deserts are essentially uninhabitable. Mostly, people live on the coast, particularly Brisbane and the Gold Coast in the south (further from the equator, since we are in the southern hemisphere).

However, a dearth of people and plenty of tropical latitudes means thousands of parks and protected areas to explore. Enough of the ecosystems have remained unspoiled, for now. Read on to discover a few of the best hikes in QLD!

Queensland is a territory more expansive than all but 16 countries. It’s impossible to isolate three of the best hikes when the choices are so many. I started with the highest mountain in QLD, one of the most scenic overnight treks, and a walking track to QLD’s most sacred summits, the Glass House Mountains.

For more information on thousands of additional hikes across QLD, check out the PeakVisor App. We’ve compiled information on all publicly maintained walking tracks across the country, formatted onto our 3D maps.

You can track your hikes directly on the app, upload pictures for other users, and keep a diary of all your outdoor adventures.

Most recently, the PeakVisor App has included up-to-date weather reports at any destination. Plus, we've been hard at work adding the details of hundreds of mountain huts and camping options.

Mount Bartle Frere may not be the tallest mountain in Australia or even a particularly tall mountain in general, but it’s one of the country’s most challenging hikes.

If you want to do this hike in a day as a mere mortal, plan for at least 12 hours on the trail. The recommended 10-16 hours encompasses the range of trail time for nearly all hikers.

The eastern side is the best but hardest route. It’s the easiest to reach from Cairns or any point along the coast, but you’ll start at nearly sea level and climb over 1,500 meters (5,000 ft) to reach the summit. For the experienced hikers among you, that elevation doesn’t sound too bad, but there are numerous other challenges.

First, the weather is generally profusely humid—otherwise, it’s raining. Some adjacent weather stations suggest this may be one of the rainiest places on the entire planet. Next, we’ve got leeches and ticks. The trail is impressively steep, with plenty of scrambling. Wet, slippery moss occupies nearly every surface. If and when you reach the summit, don’t expect to see the view of the coast and Great Barrier Reef because it’s a cloud forest that rarely sees the sun's direct rays.

So, how do we prepare for this hike? We bring a rain jacket. That’s non-negotiable. We should also check the weather to avoid the rainiest days, but it often rains here even if there’s nothing in the forecast. We should wear pants, though my girlfriend isn’t in this photo. She had to pick off many leeches. We start at the day’s first light, especially if we plan on finishing in a day. We wear our best pair of hiking boots, preferably waterproof. We bring a headlamp and a water filter.

You can also camp on the mountain and make it a two-day journey, which takes off some of the pressure of finishing in a day. But it also adds a bunch of pressure in the form of the heavy pack we have to drag up the mountain.

For a complete guide on this trail, check out this travel blog, which will tell you everything you need to know and more about this hike.

The best way to experience QLD’s Gondwana rainforests is on the epic Gold Coast Hinterland trek. The walk stretches about 60 km (37 miles), though you can extend it with various detours. Hikers generally take 3-5 days and often leave a car at either end of the trail (it’s a point-to-point). The trail traverses Lamington National Park and terminates at Springbrook National Park. Here’s an example itinerary from a local guiding company.

This one is for winter. The hike is rugged, with lots of elevation gain and loss, and you want to minimize your chances for torrential rainfall. That means the best months are June, July, August, and September.

The Gondwana rainforest is a UNESCO World Heritage Site unique to this corner of the world. Even more rare are the Antarctic Beech forests that this hike passes through, remnants of the Gondwana continent when Antarctica and Australia were connected.

The Mount Ngungun summit is an excellent place to take in the sacred Glass House Mountains. It’s also the most leisurely hike on this list!

The hike starts on Fullerton’s Road, just outside the town of “Glass House Mountains” (towns and mountains share the same name). You can find the parking lot on the PeakVisor App. After that, it’s about 1.2 km to the summit. Don’t rejoice yet; you’ll need some puff to power through the quick 200 meters (660 ft) of elevation gain. It also gets steep at the top, so watch out.

From the summit, panoramic views of the other Glass House Mountains await.

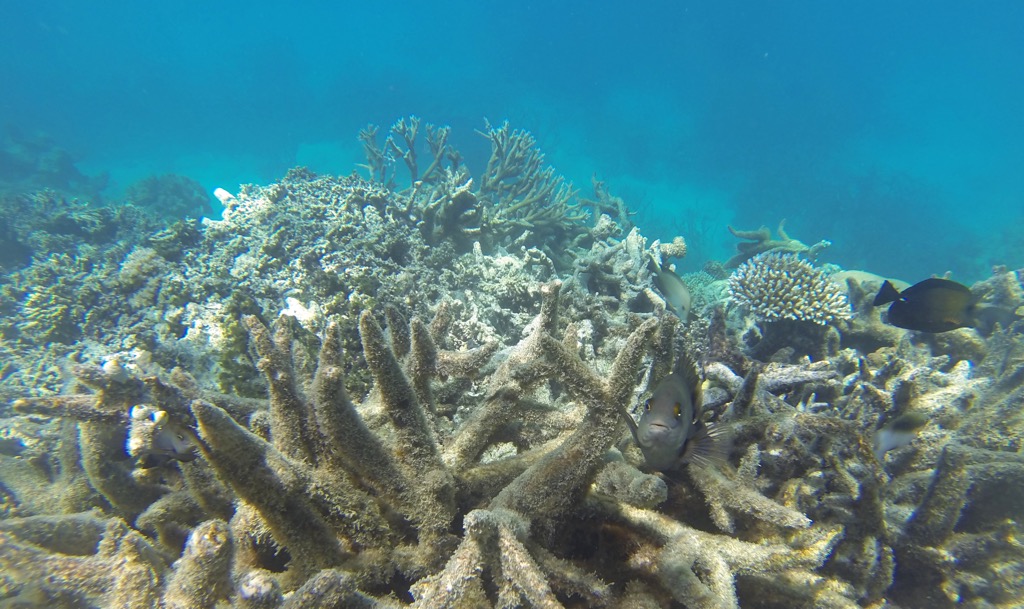

At PeakVisor, we specialize in mountains. But no article on QLD would be complete without a few words about the Great Barrier Reef, Australia’s most famous ecological wonder.

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef. Stretching over 2,300 kilometers along QLD’s coast, it’s made up of nearly 3,000 individual reefs and 900 islands. It’s an underwater world utterly different from our own, the closest thing we’ll ever experience to experiencing life on another planet.

The reef is a kaleidoscope of vibrant corals and neon-colored fish. Larger beasts include sea turtles, giant manta rays, and majestic whales migrating north-south along the Australian East Coast.

The reef has always been fragile. Scientists typically date evidence of the first reef structures to about 500,000 years ago, but the current reef is only 20,000 years old, dating back to the last ice age. Compare that to the Daintree Rainforest, which is thousands of times older.

Corals are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations. Because of this inherent fragility, reefs worldwide are among the first ecosystems to be genuinely devastated by climate change. As waters warm, corals expel beneficial bacteria and become weakened and more susceptible to disease. Corals can recover after some bleaching; 90% of living Great Barrier Reef corals have shown signs of bleaching at some point in the last few decades. The problem is that bleaching events have become nearly annual and are expected to become annual in the future. Already, the reef has lost half of its corals.

The Great Barrier Reef will continue to wither because the Earth will continue warming for decades even if we immediately cease carbon emissions altogether.

The Great Barrier Reef, not the mountains or forests (as lovely as they are), makes QLD a world-famous eco-tourism destination. Similarly, surfing—not hiking, climbing, or mountaineering—makes QLD world-famous as a sporting destination.

The whole coast is littered with surf breaks of all sorts, but none is more infamous than Snapper Rocks. It’s a right-hander point break that produces consistent waves, often large enough to barrel. The point is about 10 km (6 mi) south of the city of Gold Coast. The competitive lineup is as infamous as the wave itself.

Even if you don’t surf (like me), still go here to check out the action. The uniformity and size of the waves is astonishing, and watching some of the world’s best surfers in action on a good day is all you can ask for. If the tide and ride are right, you can watch surfers travel a full kilometer before taking a jog back along the beach.

There’s also Kirra's legendary sand point break, just a couple of kilometers closer to Gold Coast.

Cairns (pop. 150,000) is the tropical heart of QLD, where the mountainous rainforest meets the Great Barrier Reef.

Cairns is the gateway to two UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the Daintree Rainforest and the Great Barrier Reef. The Skyrail Rainforest Cableway offers a chance for families to check out the rainforest canopy; the Kuranda Scenic Railway traverses the same forest along a historic railroad.

Right in town, the Esplanade Lagoon is perfect for a curated swim in safe waters. Meanwhile, for a less curated adventure, the aforementioned Bartle Frere hike starts a few minutes down the road and climbs over 1,500 meters (5,000 ft) to QLD’s highest mountain.

Be warned: you don’t want to go here during the Australian summer (Nov. - March), the wet season in Cairns. February alone sees nearly half a meter of rainfall (20 inches). When it’s not raining, it’s blisteringly hot, and the air is saturated with humidity. Australian winter (May - October) is the best time for perfect temperatures (26℃ / 80℉) and relatively low rainfall.

Brisbane, Australia’s third-largest city, is more relaxed than its bigger southern cousins, Sydney and Melbourne. The city itself sits along the Brisbane River, with the CBD rising in a cluster of glassy skyscrapers while older wooden Queenslander houses with their signature verandas unravel across the suburbs. Brisbane’s food and bar scene has grown, but it’s still finding its feet compared to, well, Sydney and Melbourne.

Most notably, Brisbane will be host to the 2032 Summer Olympics. The city will undoubtedly see a tremendous amount of investment in preparation over the next eight years.

What Brisbane really has going for it is accessibility to more exciting spots. The city is the perfect base for trips to the Scenic Rim, including many places discussed in this article. In fact, Brisbane might be Australia’s best city concerning proximity to the mountains. Nearby mountainous parks include Lamington National Park, Mount Barney National Park, Border Ranges National Park, and D’Aguilar National Park, to name just a fraction. Hundreds of protected areas lie within a couple of hours' drive from the city center, which is nothing by Australian standards.

Brisbane is also a great base for coastal adventures, whether north to Sunshine Coast or south to Gold Coast. The best surfing is outside of Moreton Bay, which surrounds the city of Brisbane itself. Hop on the M1 south for just over an hour to reach Gold Coast, a flashy coastal city with some of the world’s best surfers (and most competitive lineups). Moreton Island and North Stradbroke Island, which form Moreton Bay, are also incredible tropical destinations in their own right.

These are a series of miniscule towns in central QLD that serve as a gateway to the Central Highlands rather than a destination in their own right. Here, we have a convenient base for exploring some of QLD’s lesser-known and emptier parks, like the sandstone cliffs of Carnarvon National Park, the craggy woodlands of Minerva Hills National Park, and the gorges and waterfalls of Blackdown Tableland National Park.

Once again, these are only a few of the scores of protected areas across this expanse of south-central QLD. And, once again, it may be tough to visit here in the summer, with temperatures prohibitive for hiking and other recreation.

Explore Queensland with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.