Introduction

Telluride sits atop the northwestern corner of the San Juan Mountains of Colorado; “Colorado’s finest range,” as legendary mountaineer Gerry Roach says. The legend of Telluride, CO, has shifted over the years. Once a bastion of powderhounds and ski bums, the town has now taken on a reputation as a getaway for society's upper crust. While the ski resort is no longer the wild-west paradise of neon jumpsuits and powder moguls, the backcountry is perhaps even more pristine than thirty years ago (due to vast mining reclamation efforts) and much more accessible. Undoubtedly, getting fresh tracks at Telluride Ski Resort has become much more challenging, although it’s still an incredible ski area (check out our guide for a full breakdown of the place). However, in my opinion, Telluride has evolved into one of North America’s finest backcountry ski meccas. You could spend a lifetime here - many have - and not ski everything. Without further ado, let’s dive into all aspects that make the Telluride region a standout backcountry ski destination and showcase several ski tours to get you started.

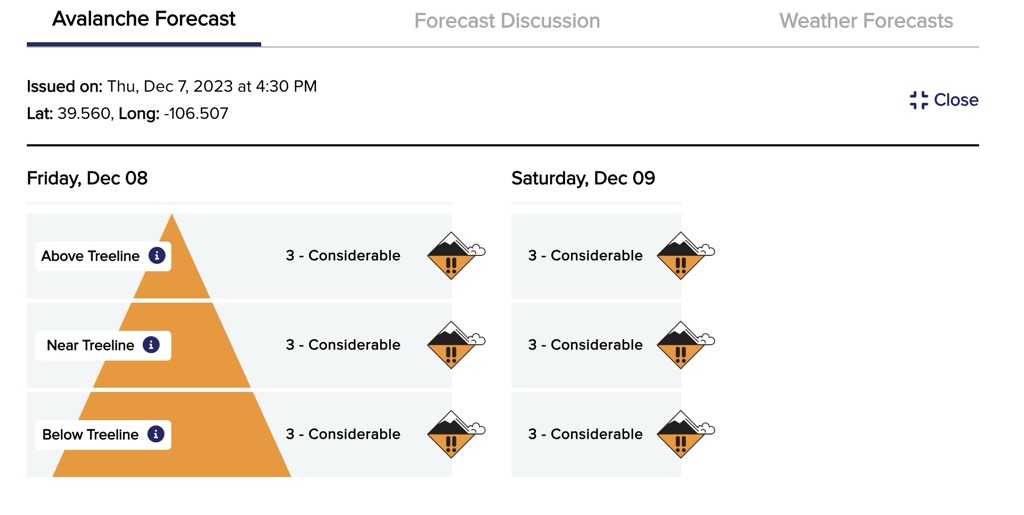

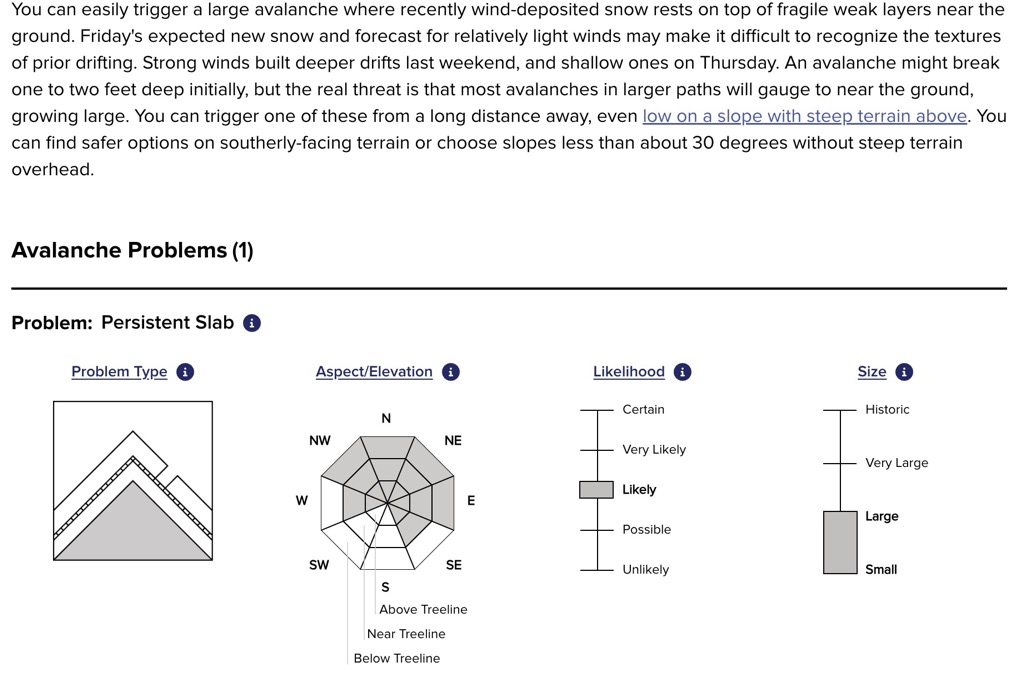

Avalanche Conditions

The terrain, snow quality, and access in the Telluride region of the San Juan Mountains make the ski touring world-class. However, avalanche risk is the most critical component of the puzzle and one of the primary reasons this area is not overrun with people.

I cannot overstate how dangerous the snowpack in the San Juan Mountains is. The Northwest San Juan region around Telluride is particularly notorious for avalanche fatalities. Considering the relative lack of people, the terrain around Telluride, Ophir, and Silverton comprises an astonishingly disproportionate number of avalanche fatalities in the U.S.

Most slides are unpredictable slabs that break over layers of weak facets. Facets and tricky avalanche conditions can form at any time during the winter. Still, the early and late seasons (November and late March to early May) are less likely to have deep instability. Meanwhile, the mid-winter season is almost always characterized by persistent instability. Because nearly all the terrain is relatively steep, skiing here is always a guessing game.

To learn more about avalanche safety and snow science basics, check PeakVisor’s Introductory Guide to Backcountry Avalanche Safety. Better yet, take an avalanche safety course; numerous guide outfitters in the region offer them on a regular basis. Critically, prospective backcountry skiers coming to the San Juans should consult the CAIC’s (Colorado Avalanche Information Center) forecast each morning before skiing. The CAIC is one of the world’s best backcountry avalanche forecasting services, and reading their in-depth discussions will help you glean information on the current state of the snowpack. You can also check the “Field Reports” page to see what sort of objectives people are going for and what types of avalanche activity they see.

The Most Continental of Continental Snowpacks

Telluride is an oasis in the middle of an inland desert, far from the nearest ocean (the Pacific is nearly 1,000 miles away). The region is host to a continental snowpack; these snowpacks are the most finicky for skier-triggered avalanches, which occur in desert regions with mountains that receive moderate snow.

Areas with the most infamous continental snowpacks include the Four Corners of the USA: Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Southern Utah. Interior Argentina around Las Leñas is also likely continental. Vast expanses of mountains in China, Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, and other Asian countries also likely feature continental snowpacks, although these are remote places where even climbers seldom venture, let alone ski.

Continental snowpacks are avalanche-prone for two main reasons. First, the temperature gradient is extreme. Bitterly cold, dry nights create a massive temperature differential with the bottom of the snowpack, which hovers around freezing. The temperature gradient encourages the formation of granular facets, which act like ball bearings. Skiers can sometimes trigger weak points in these layers, and cohesive slabs containing the entire season’s snowpack have been known to break off.

Facets usually form in the early season, when a small layer of new snow is blanketing the mountains. In continental climates, this layer is buried by additional cold, dry snow, and the facets don’t heal. In maritime climates, warmer air, rain, or heavy wet snow can heal facets that do form (although conditions are less conducive to their formation in the first place). In continental climates, facets can also form mid-season and become buried, creating a persistent slab problem even if there wasn’t one at the start of the season.

The second reason is that continental snowpacks are typically far more shallow than intercontinental or maritime snowpacks. Because skiers can only affect weak layers within a meter of the surface, skier-triggered avalanches in maritime climates are less likely. If they do form, early-season facets are quickly covered by meters of snowpack in maritime climates and usually break off or heal by themselves. The force of a skier is not nearly enough to impact these layers. Meanwhile, the snowpack depth around Telluride generally does not exceed 2.5 meters (100 inches). It is often just around one meter (40 inches), meaning skiers can still trigger those surface-level facets well into the season.

February is Historically Dangerous

Avalanche awareness is crucial any time of year while backcountry skiing in Telluride. However, in February, conditions tend to come to a head in the San Juans. By this time, the early season facets that nearly always form are buried by months of snowpack but often still within the range of what a skier’s force can trigger (one meter / 40 inches). Many accidents have occurred around this time. One classic example is the 1989 “Valentine’s Day Massacre,” in which three young, inexperienced skiers triggered a massive slide in Bear Creek. Two of them perished from massive trauma, while the third was on the verge of succumbing to hypothermia while trapped in the snow.

Telluride Ski Touring Season

In the best seasons, ski touring is possible every month of the year, although this tends to happen less often now than it did 15 years ago.

The backcountry season can start early, with some grassy turns possible by October in many seasons. One advantage of skiing in the early season is that deep facets haven’t yet formed, reducing avalanche danger.

December to February are defined snow conditions ranging from soft to deep blower powder. The limiting factor is avalanche risk, as a season’s snowpack accumulates upon an often egregious faceted layer.

March, April, and sometimes early May are the best times to pursue bigger objectives. On average, the risk of triggering a persistent slab has diminished by this time (although complex avalanche problems remain and can develop at any time). The base depth is generally at its deepest, opening up big lines. March, in particular, is still great for powder skiing, and northerly aspects hold winter snow for days if it stays cold.

Telluride Snow and Weather Conditions

Telluride is home to some of the lightest snow on Earth. On average, the snow is even fluffier than the hallowed ground of Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah (although they get far more snow than us).

The Makings of Telluride’s Signature “Cold Smoke” Powder

Telluride is nestled deep in the American Southwest, almost one thousand miles (1,600 km) from the Pacific Ocean, which generates moisture for the storms that roll through Western North America.

Deserts surround Telluride; the red rock of Moab, Utah, is less than 100 miles (160 km) away as the crow flies. The dry climate and cold temperatures efficiently produce beautifully structured snow crystals called stellar dendrites. These flakes accumulate with lots of air between the long arms of the crystals’ lattice structure. The feeling of skiing through this type of ‘blower’ powder is closer to skiing through the air than through the heavy snow that defines maritime climates like California.

The snow isn’t always super light. I’ve seen dumps of dense powder and even rain, although this is exceedingly rare. Nevertheless, the snow falls as blower powder with a higher frequency than any other place I’ve been. Better yet, the snow in the backcountry is nearly always soft. That’s because the high-altitude desert air is so dry that it effectively sucks the moisture out of the snowpack.

300 Days of Sunshine

Powderhounds relish low-visibility storm days, and even the most fair-weather skiers must accept the fact that it has to snow to make skiing possible. However, prospective backcountry visitors can take solace in the fact that the sun is shining when it’s not snowing.

Coming to Telluride on a one-week ski touring trip, there’s a good chance you’ll get fresh snow and even a great powder day. But it’s virtually certain that you’ll have at least a few beautiful days to scout some bigger objectives.

Lots of sun means that bringing sunscreen, chapstick, and sunglasses is essential. Moreover, Telluride is high-altitude and far south at only 38° latitude, two additional factors that make the sun here more dangerous.

Telluride’s Annual Snowfall

Telluride’s proximity to the desert is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the snow quality is unrivaled. However, it is quality over quantity, as Telluride does not receive tremendous amounts of snow.

From my experience during six years in town and talking with many long-time locals, it seems reasonable to place Telluride’s annual snowfall at around 250 inches. That’s about half of what famous resorts like Alta, Utah, and Palisades Tahoe, California, receive. However, the snow conditions in the backcountry are consistently better in Telluride than anywhere else in the lower 48. Telluride’s geography tends to favor smaller storms that drop a little bit of snow each day rather than big overnight dumps, making for soft conditions developing over the course of days.

Moreover, Ophir, Silverton, and the Wilson range are all positioned much more favorably for snowfall and receive significantly more accumulation than Telluride. Silverton and Ophir are likely pushing 400 inches (10 meters) per year. Depending on a storm’s direction, Ophir can receive feet of snow, while Telluride scrapes by with just a few inches.

Telluride Backcountry Ski Routes

Bear Creek

Bear Creek refers to the drainage system adjacent to the Telluride Ski Resort. The Creek is a designated preserve, meaning it’s completely undeveloped save for a few hiking trails and an old road that is now only used for hiking. Mines used to operate here, but ruins are all that remain.

The Creek is hallowed ground in the niche world of backcountry powder skiing. Telluride Ski Resort shares a boundary with this zone from the top of Chair 9 up to Palmyra Peak. The west side of the ridge comprises the ski resort, while everything on the east side is Bear Creek. An entire world of skiing extends behind the ropes that demarcate the ski resort. Some of my most profound moments on skis have taken place back here.

Skiers often divide Bear Creek into two sections: Uppers and Lowers. The Uppers refer to the terrain behind Revelation Bowl and Gold Hill, mainly in the alpine. Meanwhile, the Lowers are defined by ancient forests. The resort features five backcountry gates designed to funnel skiers into this terrain, although people often duck the rope in other spots (not condoning this).

The Creek is a dangerous place. There are a few reasons why I think it’s even more hazardous than a pure backcountry zone. First, the lift access allows you to ski terrain without having first skinned up, which often results in ignorance about avy conditions. Secondly, while the skiing is challenging, the route-finding and avalanche situations are even more complex. You could be perfectly capable of skiing the terrain back here, but to safely descend, you need mountain sense.

Lastly, another critical safety hazard in the Creek is the sheer number of skiers above you at any given time. Frankly, the Creek is a horror show of skiers with varying levels of experience coming down on top of one another. Try not to ski on top of others, and be aware that there are likely very inexperienced people skiing back here who may unwittingly ski on top of you.

For the reasons above, I didn’t map out the lift access routes on the lowers and uppers. The last thing the Telluride ski community needs is more unwitting skiers following a track and dropping in on top of one another. You’ll have to earn the trust of a local or follow your nose (after all, Tempter is already a piste within a few days after a big March dump).

A generation of Lower Bear Creek using PeakVisor’s mobile app. Check out the app to find thousands of lifts, trails, ski tours, peaks, cabins, and even parking areas in the Telluride, the U.S., and worldwide. It’s all on here. You can also upload .gpx files if we don't already have a trail on our servers. The PeakVisor app is available for iOS and Android; give it a shot and discover our visually stunning 3D Maps, adding a new dimension to your alpine adventures.

My advice to those looking to start exploring the creek is to find a safe, knowledgeable partner and don’t start skiing back there until you feel very comfortable ski touring in the backcountry; that means putting in 3000 ft days (900 m) on skins and safely navigating in the mountains.

San Joaquin Couloir

Difficulty: Difficult

Avalanche Risk: High

Elevation Gain: 1,000 ft (300 m)

Departure: Top of Gold Hill, Telluride Ski Resort

Aspect: North

The San Joaquin is the most celebrated and photographed line in Bear Creek. It’s just so aesthetic. Is it the best line? In my opinion, no. But it’s an absolute classic and a must-do in the Creek.

Most skiers approach from the north-facing side, looking at the couloir, because the lift boosts you to 12,500 ft (3,810 m). After disembarking the Revelation Bowl lift in the Telluride Ski Resort, head out along the cat track that traverses Gold Hill. You’ll be walking toward the in-bounds Gold Hill Chutes 7-10.

After 20 minutes, the Gold Hill Chutes appear on your right, and the expanse of Delta Bowl drops to the left. You’ll have to drop to the left but resist the temptation to ski Delta Bowl. Traverse across the bowl until you’re about under the couloir. Alternatively, you can continue hiking and drop into a south-facing couloir called Double Trouble, cutting right and staying high (this saves you some skinning).

Strap on the skins and head up along the right side of the buttress to drop into the couloir. In my experience, ski crampons often help during this skin; it’s a real pain trying to keep an edge on some of the steep, windblown sections along the buttress without them.

Although it looks vertical from the resort, the San Joaquin tops out at about 48° at the choke, with most of the couloir hovering in the 45° range. It’s a perfect introduction to steep skiing, though you should be comfortable with a jump turn before dropping in. More than the steepness, perhaps the most significant danger is the possibility of a windslab at the top, as the bowl leading into the couloir steepens and narrows.

After the choke, the passage widens, and you can open it up coming out onto the apron. It’s a powder finish for an epic couloir descent. The turns on the apron are nearly always soft and fun but don’t expect powder in the couloir even with fresh snow. New snow often flushes out naturally, and the surface is usually variable to some degree until after the choke.

Wasatch Face

Difficulty: Difficult to Extreme

Avalanche Risk: High

Elevation Gain: 1,000 ft (300 m)

Departure: Top of Gold Hill, Telluride Ski Resort

Aspect: West

The Wasatch face comprises the ridge on the east side of Bear Creek, facing the ski resort. These are some of the most coveted lines in the Creek, sometimes not coming into condition until late in the season. They are very aesthetic and also perfectly visible from the Revelation Bowl deck, so you can occasionally have a crowd of people watching you.

Getting to the ‘Satch involves the same approach to the bottom of the San Joaquin couloir. From there, fire up the skins for a short but steep hike across the Creek and up the opposing ridge to the east. For Bearface, the first bowl on the lookers’ right, you can cut under the ridge. For everything else, gain the ridge by following a gully feature to the lookers’ right of Bearface (the prominent cirque). You should shoot for the saddle directly below Wasatch Peak, 500 ft (150 m) above to the right.

Traverse north (left) to find the line you seek (dropping back left, of course); in order, you’ve got the Bearface, the Wave, the Banana, Heaven’s Elevens, the Grandfather, and the Y.

Wilson Peak

Difficulty: Extreme

Avalanche Risk: High

Elevation Gain: ~5,000 ft (1,500 m)

Departure: Rock of Ages Trailhead Rd.

Aspect: North

Wilson Peak is listed in the 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America book; therefore, for more beta, you can read the book or watch Cody Townsend’s The Fifty episode.

The day begins with finding the Rock of Ages Trailhead Rd., off from Silver Pick Rd., and getting as far up the road as possible. The route is generally completed in April as the snowpack begins to stabilize with warming temperatures, so you can often drive quite far up by this time.

Start skinning through the forest and up into a large bowl. The goal is to gain the ridge, cross it, and eventually gain Wilson Peak’s southwest ridge. From here, it’s a steep climb up to the summit or the northwest couloir; the NW couloir avoids the final scramble to the top and is not as steep of a descent.

The main couloir on the “Coors Face” descends from near the summit. Depending on the year and the snow depth, some route-finding around rocks is required. It’s quite steep and exposed; you won’t want to take a fall here. After navigating the couloir and bowl below, it’s best to stay high and left to traverse around the northwest shoulder of Wilson Peak and back toward your uphill route.

Ophir Backcountry Ski Routes

In the Bible, Ophir is the name of a mythical kingdom reputed to be rich in gold. Miners first struck gold in Ophir, Colorado, in 1875, after which the town sprung up. The boom petered out by the early 1900s, and only a single resident remained by 1970.

Ophir’s second life paralleled the rise of Telluride Ski Resort, as the town is only 25 minutes away. Today, Ophir has a reputation for having an even more hardcore ski vibe than T-town, primarily due to the access to backcountry skiing. Classic ski lines are peppered throughout the tight valley. Access involves parking your car and walking for 30 seconds into the forest.

On the south side of the valley, Waterfall Canyon and Swamp Canyon are the two largest and most popular zones and are the most accessible from the town of Ophir. However, Trout Lake is the best access for the chutes at the back of Waterfall Canyon. The valley’s north side is a series of south-facing avalanche paths that offer broad and open descents. Several decades ago, one of these paths took out most of the town, dividing the remaining sections into East and West Ophir. Skiing from Telluride Ski Resort to Ophir is the most classic way to get one of these lines in condition while saving some puff.

Ophir is defined by its die-hard ski community, many of whom would be disappointed to see an article on the internet mentioning their fabled ski grounds. Nevertheless, Ophir already caters to visitors through the famous Opus Hut, which sits near the top of the Ophir Pass. You can also hire a guide through regional outfitters like Mountain Trip or San Juan Mountain Guides.

Lastly, Ophir is infamous to skiers who follow the CAIC’s accident report due to the overwhelming number of avalanche fatalities that occur in the area, the most recent being on Jan. 23rd, 2024. Ophir gets a lot of snow, and the authorities occasionally bomb some slopes to protect houses and infrastructure. The snowpack usually remains sketchy throughout the winter.

Jane’s / Mustang

Difficulty: Easy/Moderate

Avalanche Risk: Low/Medium

Elevation Gain: ~2,000 ft (650 m)

Departure: West Ophir

Aspect: East

I don’t feel bad spilling the beans about this zone because it’s already like the Ophir Ski Resort. With plenty of Ophiridians on dawn patrol, there’s always somebody ahead of you on the skin track here. Luckily, there’s also plenty of space to spread out.

This zone occupies the lower reaches of Yellow Mountain, on the Waterfall Canyon side. You can start right from town in West Ophir (the town was split in two by an avalanche, and this is the section you come to first when driving). However, be considerate when parking because the town has had issues with parking overflow around residences.

Follow the northeast shoulder of Yellow Mountain up through the trees until you reach the treeline. Jane’s is the obvious path dropping off to the left (it will have tracks in it), while Mustang starts just a bit higher. As a heads-up, Mustang has a few tricky kick turns just before the top. Of the two, Mustang is more prone to avalanches, especially as you come out of the trees into the steep open meadows. Watch out for terrain traps.

Swamp

Difficulty: Moderate

Avalanche Risk: Moderate

Elevation Gain: 2,300 ft (700 m)

Departure: East or West Ophir

Aspect: East

Swamp is the other easy local classic, with the skin track starting just on the opposite side of Waterfall Canyon. During sketchy avalanche years, it’s difficult to ski much besides Jane’s, Mustang, and Swamp until the facets mellow out in the spring.

Swamp is also fun as a nice loop. The skin track follows the east flank of Waterfall Canyon. As you gain the ridge, head right (south) around a large bowl. You’ll reach a crest, then drop off to the right of the steep bowl. These sparsely tree’d meadows are perfect for powder turns, and there is plenty of room for everybody to spread out.

After the series of meadows, trend left to rejoin an old mining road back to Ophir. If you go too far down, you’ll end up tangled in willows at the bottom of the canyon, which is called Swamp Canyon (the run is named after it).

The Magnum

Difficulty: Difficult

Avalanche Risk: Moderate/high

Elevation Gain: 3,700 ft (1,100 m)

Departure: East Ophir

Aspect: Northwest

The Magnum is the prize line descending from South Lookout Peak, one of Ophir's proudest summits. It’s a classic for those staying at the Opus Hut, just up on Ophir Pass.

The Magnum is couloir skiing at its finest. The couloir is broad, with plenty of room to spread out, and it maintains an impressively consistent and steep slope angle of around 40°.

The run has a fair bit of northern exposure, so the snow can stay good after a storm. However, most folks wait for the facets to settle out before hitting this one. The other issue with getting this couloir in powder is the fact that you have to bootpack up the entire thing, which expends an incredible amount of energy in deep snow. I’ve always waited until spring for this one, for both avalanche safety and firm snow on the bootpack.

The ascent starts by heading up Ophir Pass Road and then veers right into Swamp Canyon. You can stay on the same mining road that takes you down from the classic Swamp descent, or you can ski Swamp first and put yourself at the base of the apron. Continue skinning up the apron; you’ll transition to a bootpack around the couloir's base. The couloir forks toward the top, and both the left and right variations are skiable.

After completing the Magnum, you’ll just have to look up Swamp Canyon to find inspiration for the next ascent. The whole canyon is littered with couloirs and faces.

Silverton Backcountry Ski Routes

Silverton is a backcountry skiing mecca unmatched in Colorado. The town sits in an ancient caldera volcano that now resembles a small, flat valley surrounded by mountains. The location is more favorable for orographic snowfall; the positioning of the mountains allows both southwest and northwest winds to deposit snow here. Therefore, Silverton gets about 30% more snowfall than Telluride.

The upper Animus River runs through Silverton. Several smaller river valleys join the Animus and extend out of the main Silverton valley. Various forest roads—most remaining plowed in the winter—provide access to these zones.

McMillan

Difficulty: Easy

Avalanche Risk: Low

Elevation Gain: 1,500 ft (450 m)

Departure: Top of Red Mountain Pass

Aspect: Variations of West

McMillan is one of the easiest ski tours in the San Juans and, consequently, one of the most crowded. You can always expect to see dozens of other people, and the run gets incredibly tracked up; you could just find slopes at Telluride that had fewer tracks than this on most days.

That said, it’s a beautiful zone. The slope angle remains about 20° throughout, a rarity in the San Juans. On good years, the west slopes of McMillan resemble glacier skiing. For fewer tracks, check out the southwest slopes (picture below).

The approach is neither strenuous nor technical. Start at the top of Red Mountain Pass at the entrance to County Rd. 14 (totally snow-covered), where there is a small plowed pull-off that can fit maybe a dozen cars. Head east up County Rd. 14, passing the St. Paul’s Lodge (I’ve used their outdoor pit toilet a time or two). Continue east out of tree line, heading up the gentle slope toward McMillan. You don’t even need to zig-zag your skin track; the slope angle is that mellow.

To make McMillan a bit more exciting, you can ski off the backside, which consists of generally east-facing gully systems. It’s much steeper back here, and there are plenty of options, but avalanches are a genuine concern; these are all large bowls funneling into gullies that act as significant terrain traps. This takes you to Cement Creek and County Rd. 110, just across from Silverton Mountain Ski Area. Shuttling these runs can be a blast. If you have four people, one person can take turns driving while the others climb and descend (laps would be around 1.5 hours for a speedy group). You gain about 1,100 ft (325 m) extra vertical descent this way.

Turkey Chute

Difficulty: Difficult

Avalanche Risk: Moderate/high

Elevation Gain: 2,800 ft (850 m)

Departure: Arrusta Gulch (County Road 21)

Aspect: Northeast

Turkey Chute is the classic big objective in Silverton and sits just below Hazelton Mountain. With plenty of northern exposure and high walls shading the couloir from the mean old sun, the snow starts sticking early. The couloir was traditionally in condition by the end of November, hence the name Turkey Chute (a reference to the Thanksgiving Holiday at the end of November for our international readers). Likewise, the snow and coverage stay good through April.

For the approach, park at Arrusta Gulch and head up County Rd. 21, quickly turning left onto County Rd. 20 after crossing the Animus River. When the road begins to track west, turn left (south) and continue until you break out of the treeline into a large basin. Follow the basin straight up, sticking to the less steep chutes on the right for the skin track. Still, you’ll need some kick turn for the headwall here and then again to gain the couloir's entrance, which appears as a saddle on the left, just below the summit of Hazelton.

The descent itself offers almost 2,000 ft (600 m) of couloir and apron skiing, with the remainder of the vertical burned up on the traverse back to the car. The couloir is steep but not too steep, likely around 40°. Overall, it’s a straightforward mission that usually takes a few hours. Still, avalanche risk, variable conditions, and the steep kick turns heading up to the entrance merit a “difficult” rating for this one.

After the apron, traverse left and stay high to give yourself leverage for the traverse back to County Rd. 21, which you follow down to the car.

Shady Lady

Difficulty: Extreme

Avalanche Risk: Moderate

Elevation Gain: 2,300 ft (700 m)

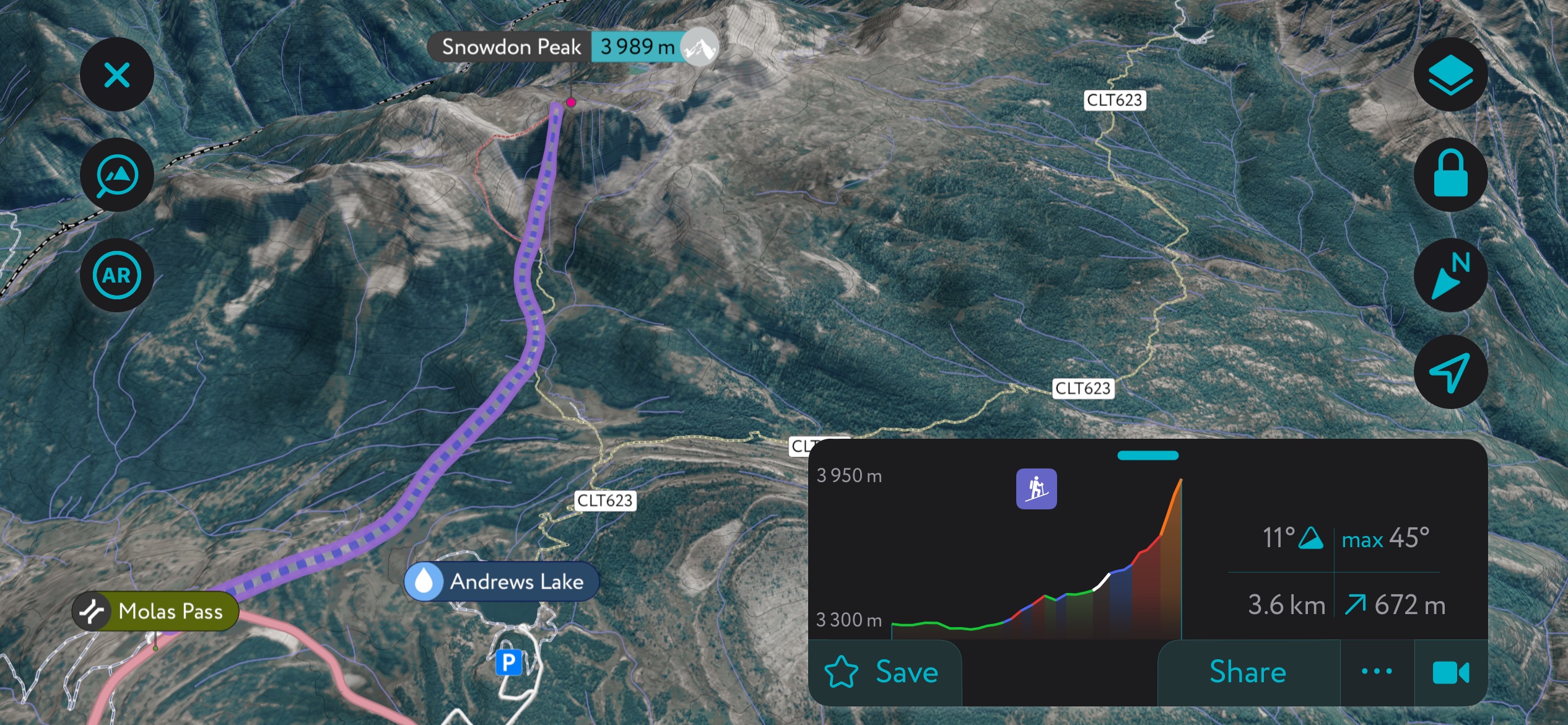

Departure: Top of Molas Pass

Aspect: Northwest

Silverton was once a bustling mining camp and home to several “houses of ill-repute.” Some would say that the Shady Lady Couloir, located on the northwest flanks of the iconic Snowden Peak, resembles the silhouette of a voluptuous woman.

For the approach, you can begin at a few different parking areas atop Molas Pass, heading south out of Silverton. The route trends southeast through the forest toward Snowden Peak. It can be hard to orient yourself as you wind through dense forests interspersed with gullies and other annoying terrain features (for skinning, at least). You don’t get many views of Snowden until you pop out at the base; this is a route where an app like PeakVisor might help you with navigation.

Skin as far as you can up the apron, then prepare for a steep bootpack up the couloir. Come prepared with an ice axe and crampons for this adventure. The ascent can be varying levels of spicy depending on snow conditions. There is only a tiny space at the top for transitioning, so this line is best for parties of just 2-3 people. Ski back the way you came.

I rated the avalanche hazard as moderate because the couloir likely flushes itself out due to its steepness. Plus, unlike in the Turkey Chute, you have the advantage of observing the snow conditions before skiing. Still, even a small avalanche or slough is dangerous if it’s significant enough to knock you off your feet. Depending on the conditions, a fall here could be fatal.

Kendall Peak

Difficulty: Moderate

Avalanche Risk: Moderate/high

Elevation Gain: 3,700 ft (1,130 m)

Departure: Silverton downtown

Aspect: Northwest

Every mountain town has its flagship peak, one that watches over the community day in and day out. Kendall fulfills that niche for Silverton. The peak rises nearly 4,000 vertical feet above town; the foot is just a few blocks from Main Street. There is a microscopic ski area - Kendall Mountain Ski Area - that serves exclusively beginner terrain, and the Silverton community and government have long been embroiled in a debate about the expansion of this area. Years ago it seemed that a gondola might eventually run to the summit, although these plans seem to have lost support. The area will likely remain a backcountry hub for the near future, although some development seems inevitable over the coming years.

For backcountry enthusiasts in top physical condition, the mountain remains one of the best touring options in Silverton. The approach is straightforward, at least from a route-finding / skinning perspective, and the descent is incredible.

The approach starts just blocks from Main Street up County Rd. 33. Follow the easy road grade for 3,700 vertical feet (1,130 m) until you reach the summit, staying left at a few junctions along the way. It’s a long skin but is very technically easy. Don’t get too complacent, though, because you will be exposed to avalanche paths as you wind along.

As you look down at the town of Silverton from the summit, several descent variations present themselves. In classic San Juan style, the mountain is defined by several large alpine bowls at the top, which constrict into gully systems toward the bottom. The avalanche hazard is obvious. Rejoin the road toward the bottom and glide right back into downtown.

Battleship

Difficulty: Moderate

Avalanche Risk: High

Elevation Gain: 2,700 ft (800 m)

Departure: Parking along the 550

Aspect: East

There are about two dozen mega classics in Silverton that could be featured in this guide, but with limited space, I think Battleship is worthy of a spot. It’s one of the most iconic peaks in Silverton, towering over the 550 with tantalizing ski lines trickling down from the summit. It’s one of those peaks with the perfect mix of trees and open space and is right in the 35° sweet spot.

There’s parking along the 550 or at the base of Ophir Pass (County Rd. 8 - closed in the winter). Follow the northeast shoulder through the forest. The summit is barely in the alpine, so this is a decent option on low-visibility but stable days. Several bowls offer perfect skiing through small trees, funneling into larger avalanche paths toward the bottom.

Battleship is a popular but deadly classic, and skiing here mid-winter can be a guessing game. That said, the conditions tend to deteriorate in the spring; the best corn snow is found higher up in the alpine. At the end, there’s a manageable creek crossing to get back to the car.

Location / Getting to Telluride

Telluride sits atop the northwestern corner of the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. Telluride is just a few miles as the crow flies from Ridgway, Ouray, and Silverton, CO, although driving takes much longer due to winding roads through the mountains.

Telluride is ultra-remote in terms of the nearest major city, a notable factor in limiting crowds during the winter (the other being cost - more on that later). The town is about six hours by car from Denver, Colorado, Salt Lake City, Utah, and Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Driving

Getting to Telluride is trickier than most other Colorado resorts, hence the mountain's relative lack of skier traffic.

It’s a six-hour drive to Telluride from the nearest large cities. Be wary of winter weather on the way over. It’s essential to have, at a bare minimum, snow tires, even if you plan on staying on the highway. I-70 regularly turns into a parking lot, and tourists take a lot of wrath from locals for being unprepared to drive in the snow.

Check the CDOT Website for a full update on road conditions, complete with webcams. As I’ve mentioned, having snow tires is essential, but 4x4 or AWD is also ideal. If you only have 2WD, carry chains and know how to put them on.

Nevertheless, the roads are usually passable, and the drive is beautiful. I’ve always found it easy to drive all day in the Western US. For this reason, Telluride gets a lot of visitors who drive in from far out of town.

Flying

Most people flying to Telluride arrive via Montrose Airport, where they rent a car or get picked up by a shuttle (Mountain Limo and Telluride Express are the most popular). Although Montrose is a small airport, it’s easy to obtain a connection from anywhere in the U.S. because they have daily service from large airports like Dallas and Denver.

Flying into Telluride airport is also possible. The airport was for private jets for years but has recently begun public service.

Check out the resort's webpage for details about your Montrose or Telluride flight.

Tourist Information and Guiding Outfitters

The Telluride Visitor’s Center is host to a friendly, knowledgeable crew of locals and every brochure you can possibly imagine.

Telluride Visitors Center & Tourism Board

236 W Colorado Ave.

Telluride, CO 81435

Hours: 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., daily

Website: https://www.telluride.com/plan-your-visit/visitors-center/

Mountain Trip

135 W Colorado Ave #2a

Telluride, CO 81435

Hours: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday

Website: https://mountaintrip.com/

San Juan Mountain Guides

710 Main St

Ouray, CO 81427

Hours: 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m., daily

Website: https://mtnguide.net/

Nearby Ski Resorts

It’s always a blast to link some resort days with those backcountry missions. Here are the top locales with spinning lifts, including the resort in Telluride.

Telluride

Telluride Ski Resort is one of the most magnificent in North America. Unfortunately, from a price perspective, the resort is ultra-exclusive for most people. This is especially unfortunate because the skiing caters so well to the lifelong expert ski bum.

Readers of this guide will already know that the resort offers access to Bear Creek, the best backcountry available from the actual town of Telluride. The Creek is undoubtedly on par with the best lift-access backcountry in North America.

Telluride Ski Resort itself features 148 individually named slopes and 19 ski lifts. The lift-access skiing tops out at over 12,500 ft (3,810 ft), while in-bounds hike-to terrain accesses an additional 600 ft of vertical, topping out at over 13,000 ft (4,000 m). Most skiers consider Telluride an advanced ski mountain, but the resort caters well to beginners and advanced skiers. In contrast, intermediate skiers who cannot graduate to black slopes may find Telluride limited.

Crested Butte

The Butte offers some of Colorado’s finest lift-access skiing. The mountain is shaped like a Hershey’s Kiss, meaning the lower mountain is mellow and perfect for beginners, while the upper mountain is steep and gnarly, ideal for experts and powderhounds.

The town is in a Victorian style similar to Telluride, with cute, multi-colored facades and western charm. Along with Telluride, it’s one of the most charming ski towns in the U.S. The only shortcoming with the Butte is that you have to drive 15 minutes up to the mountain village to ski (there are also plenty of buses).

Crested Butte was once relatively uncrowded. Unfortunately for locals, that changed when Vail bought the mountain seven or eight years ago. Most days are manageable, but the lifts can get crowded on weekends and powder days because of the newfound ease of access for front-range epic pass holders.

Silverton Mountain

Silverton Mountain is an anomaly among lift-access ski areas in the U.S. A single, ancient two-seater chairlift services the mountain, ascending about 2000 vertical feet (600 m). An additional 1000 ft or so (300 m) is accessible via hiking along the ridge that divides the area’s east and west aspects.

There are no pistes; the skiing is an assortment of bowls, couloir, faces, and trees. The terrain is steep and exciting, and the resort markets itself as a lift-access backcountry mecca with avalanche control. Silverton has the advantage of snowfall from the north and south, which means they get about 30% more snow than Telluride. Silverton Mountain likely averages more than 350 inches (9 m) of snow per year over Telluride’s 250.

Silverton does offer an unguided pass for 25 or so unguided days in March and April. The unguided season pass used to be $200, but in the last couple of years, it has increased to $700 with no discernable advantage.

I’ve had some fun days at Silverton unguided. However, I’m not much of a fan of Silverton for several reasons:

- It’s guided-only skiing during most of the winter, meaning you must pay about 300 dollars to ski with a group, with a guide managing your every move (ski next to my tracks, etc.).

- There’s not much north-facing terrain, so the snow is often sun-affected starting in March.

- The best routes are only accessible via hiking along the ridge, sometimes for up to an hour. I enjoy earning my turns, but when I do, I prefer not to pay money for it.

- Waiting for the bus at the bottom for backside runs adds another step to the process of doing a lap.

- The above comes at a lofty $295 per day during core season weekends. Want to avoid skiing with strangers? A private guide will cost you a tantalizing $2000 for one day. And no, in case you were wondering, these guides are not IFMGA certified.

The unguided season starts in mid-March. By this time of the year, it can be hard to get excellent conditions on the mountain because of the lack of north-facing terrain. In the dozen or so unguided days I’ve done at Silverton, I’ve had crusty conditions for about 10 of them. That’s why they offer an unguided season - it’s not worth the money clients would have to fork over for guided, and they know that.

When you get a big storm, the mountain is often shut for avalanche control, and rope drops are met with frothing hordes of powderhounds. You might snag a few soft turns between the guide tracks, the avy debris, and bomb holes.

The unguided season $40 heli drops are a complete gimmick. The helicopter flies about 90 seconds across the valley to drop you off on a tracked-out bunny slope. It’s basically for Instagram. Even the regular heli drops, almost $200 a pop, don’t go anywhere you can’t hike to in a few hours.

Silverton once fostered a scene of backcountry enthusiasts but has slowly been widdled down into a profit machine that caters more to novices with disposable income. I guess…at least it’s not owned by Vail?

The town of Silverton and the surrounding mountains are one of the world’s true backcountry skiing meccas. I recommend using the PeakVisor app and exploring the mountains, where you can find both solitude and fresh tracks. I’ve even uploaded some of the classic routes to get you started.

Durango Mountain Resort (Purgatory)

Durango is one of my favorite Colorado towns. It sits at the base of the San Juan Mountains, about a two-and-a-half-hour drive southwest of Telluride. Their local ski hill was recently rebranded Durango Mountain Resort, although everybody still calls it Purgatory. Purg has a great family vibe and some fun intermediate slopes. When storms come from the south, Purgatory can sometimes snatch magnanimous amounts of snow.

The town of Durango is also worth a visit during any season. Backcountry skiing in the southern San Juan Mountains is excellent, with Durango having the best access to Coal Bank and Molas Pass. Mountain biking and rafting in the summer make Durango a year-round destination.

Purgatory Ski Area