It was the middle of May in the San Juan Mountains of Southwest Colorado, USA, and thanks to some late-spring storms and clear, cold nights, our snowpack was still relatively fat, at least in the high northerlies.

So far, we had been spared the dreaded red dust that tends to blow in from the Utah desert and decimate our snowpack, just as the snow turns isothermal and avalanche danger goes green light.

Meanwhile, below treeline, the season was decidedly spring. Amidst the verdant greens, rolling rivers and streams, it was undeniable that winter had fled south and spring had sprung in its place. Telluride was a ghost town. With the gondola shuttered, Main Street was dry and dusty, devoid of tourists, second homeowners, and even most of the locals.

It was not only off-season. It would be more flattering to describe this time of year as fourteener ski season: when peak snowpack, high-pressure, sun angle, avalanche problems, and overnight temps have the potential to achieve the happy-medium required for safe, steep, ski touring in high consequence, exposed terrain that tops out above 14,000 feet of elevation.

When you can still ski all the way back to your truck, bask in the warmth of the mid-day sun, bare feet dangling under the tailgate, while making plans to do the same thing the next day? And maybe even the day after that? Now that’s fourteener ski season.

It was a welcome respite from our infamously touchy and unstable continental snowpack in the place we call home. It is the time of year when otherwise dangerous, slabby, and/or rock-peppered couloirs are transformed into smooth, stable, steep hallways lined with uninterrupted corn snow… granting safe passage and soft turns to those with the passion and good fortune to nail the fickle timing of a freeze-thaw cycle.

Catch it too early and you accept the penalty of climbing all morning in rock-hard snow only to make your ski descent in similarly firm, puckering conditions. Get there too late, and your corn is cooked, lacking the cohesion and substance to support the weight of you and your skis and increasing your exposure to hazards like rockfall and wet slides. It’s a fine line, and anything less than Goldilocks conditions just won’t do on the most committing of 14ers.

Ski season around here can start as early as October, and this go-round was no exception. So, by the time May rolls around, 7 months into ski season, chair lifts hanging idle for weeks, the attention and focus of even the most devoted skier can sometimes wander…

It had been a couple of weeks since my last ski tour, having briefly traded ski crampons, skin wax, too-tight touring boots, and early ups for 29” tires, Chacos, and lazy mornings waiting for the sun to get a little higher.

Sure, it was nice and easy.

And mountain biking is pretty fun.

But the truth is, by the time the San Juans came into view, I had all but forgotten about riding bikes and was dreaming of high peaks, sunshine, and corn snow. Just before I lost cell reception and began the descent from the Dallas Divide with Ralph Lauren’s ranch already glowing in the pre-golden hour, my phone rang, and I pulled over.

I knew the caller wanted to go skiing, and I was game.

The objective: the Northeast Couloir on Wilson Peak.

It’s known as Shandoka, the “Storm Maker,” by the Indigenous Ute Tribe, and known as the “Coors Mountain” by heavy drinkers, Texans, and those who don’t know any better.

At 14,021 ft (4,274 meters), the North Face of Wilson Peak looms large from Telluride Ski Resort and Mountain Village, inspiring the daydreams of skiers of all abilities. The mountain was named for A.D. Wilson, the chief topographer of the Hayden Survey. Nearby Mount Wilson also honors him.

To those who live in its shadows, Wilson Peak isn’t just another mountain. It’s iconic, quintessential, mythical. A jagged, rocky, steep, imposing pyramid that seemed to beg the question: “Does it get skied?”

Although I knew the answer, it was hard to visualize from the valley below. Every year, depending on the snow, the classic line looked and skied a little (or a lot) differently than years past. That is if it was even skiable. Some years, it wasn’t.

Part of the 3-headed massif that includes Mount Wilson 4,344 m (14,252 ft) and El Diente 4,317 m (14,165 ft), Wilson Peak is in the Lizard Head Wilderness of the Uncompahgre National Forest near the town of Telluride, Colorado, in the San Juan Mountain range.

It is one of Colorado’s 52 “fourteeners” -- mountains that scrape the sky, rising over 14,000 feet in elevation. Aside from its historical relevance to the native people, the mountain has achieved considerable notoriety over the years as the poster child for Coors Light advertising and its image on the beer label.

Wilson Peak has remained newsworthy thanks to its inclusion in the 2010 book 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America, written by Chris Davenport, Art Burrows, and Penn Newhard and published by Capitol Peak Publishing.

After querying my partner with several pointed questions about anticipated weather, snowpack, and conditions, we agreed on a start time for the formidable objective, and I began packing. It was all the usual ski touring gear, plus the pointy stuff, like ice axe, whippet, ski crampons, and boot crampons. I took the extra time to lay out all the gear and supplies necessary for the trip and examine it closely. The top of Wilson Peak was the last place I wanted to discover something had been broken or left behind.

Sleep did not come easy that night… in fact, with the prospect of the next day’s adventure pinballing around in my brain, I’m not sure it came at all. Jake picked me up in his Red on Maroon BullNose F-150, nearly as classic as Wilson Peak, and we began the drive to the Rock of Ages trailhead by the dawn’s early light.

It was French press coffee for me and Mate for him, but before we even arrived, there were obstacles to overcome in the way of downed trees that spanned the snow-covered road to the trailhead. Without a chainsaw or even an axe, we were ill-prepared for such a hindrance, costing us precious time and energy. And so close to the trailhead. After taking turns with a handsaw only to find yet another down tree around the corner, we decided to park the truck and start touring from just under 9,600 ft.

As anticipated, the snow was firm, and the sun crust supported our skis for the first couple hours of skinning, making for quick and easy travel to the base of the west-facing chute that stood between us and the summit of Wilson Peak. We stopped for the first time since leaving the truck and transitioned to boot packing: skis on the pack, helmet on head, boot crampons, ice axe, whippet. After a snack and water, we were on our way. There was no time to waste, with the sun warming the chute and overhead rockfall danger, probably the most significant objective hazard on the way up.

As we approached 14k feet, we found ourselves in a sunny west-facing chute. It was an equal mix of chossy, lichen-coated conglomerate and old rotten snow.

Topping out on the snowy summit of Wilson Peak with skis on your pack and a solid partner by your side has the makings of an adventure that an old ski mountaineer will cherish for all his days. All of the San Juans were laid out before us, with the La Sal Mountains to the West. On the clearest of days, you can see all the way to the Henry Mountains of Central Utah, hundreds of miles to the west.

As much as it would have been nice to linger on the calm summit, it was hard to ignore the fact that finding the entrance to the line was likely the crux of the entire ski tour. We headed north on the flat summit snowfield toward what we guessed would be the best way into the Northeast Couloir. There were no tracks to follow.

With skis on our packs, we carefully kicked steps downhill into the most likely entry point. It was thin and rocky off the summit, and we could only hope conditions would improve as we got into the somewhat protected couloir.

From there, a short scree-snow traverse above significant exposure led us to the goods. Once we reached the proper couloir,, it became clear that the snow was not only soft but supportive. The line was filled in and continuous as far as we could see until it rolled over thousands of feet below us.

With skis on our feet, tech toes locked out, and a continuous strip of ripe and rippable corn snow below us, Jake and I shared a knowing smile as we began the second half of our biggest adventure to date.

I went first with an exaggerated jump turn in the steepest part of the line, at around 50 degrees. The avalanche hazard was low and the only real danger would be of the wet-loose variety once we got lower—that or falling, which wasn’t really an option.

Either way, we took it slow, leap-frogging from safety to safety. This was big mountain terrain, and we both shared the same level of caution and respect toward the peak we had admired and wondered about over the past decade.

As we continued into the heart of Wilson Peak, the pitch decreased, the width increased, and careful jump turns gave way to faster, looser skiing. Once safely at the bottom of the Northeast Couloir, we milked the last of the smooth corn turns before embarking on a seemingly endless westward traverse toward the truck and trailhead.

The rest of the tour was, thankfully, uneventful, and we arrived at the truck feeling tired and satisfied to have checked off one of the biggest and best ski lines in the San Juans in prime conditions. We both agreed that it would be fun to ski this one again in powder snow…maybe someday!

Using the PeakVisor App

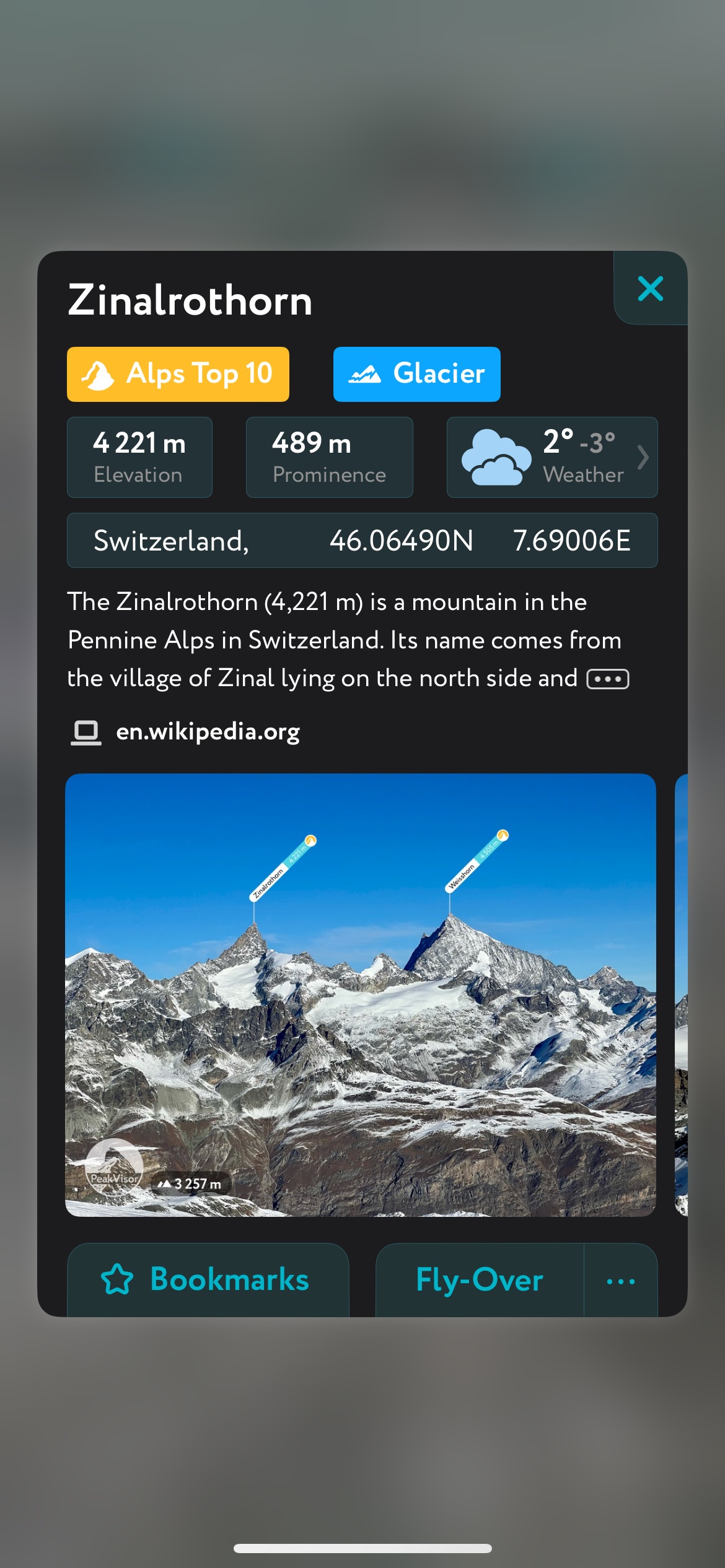

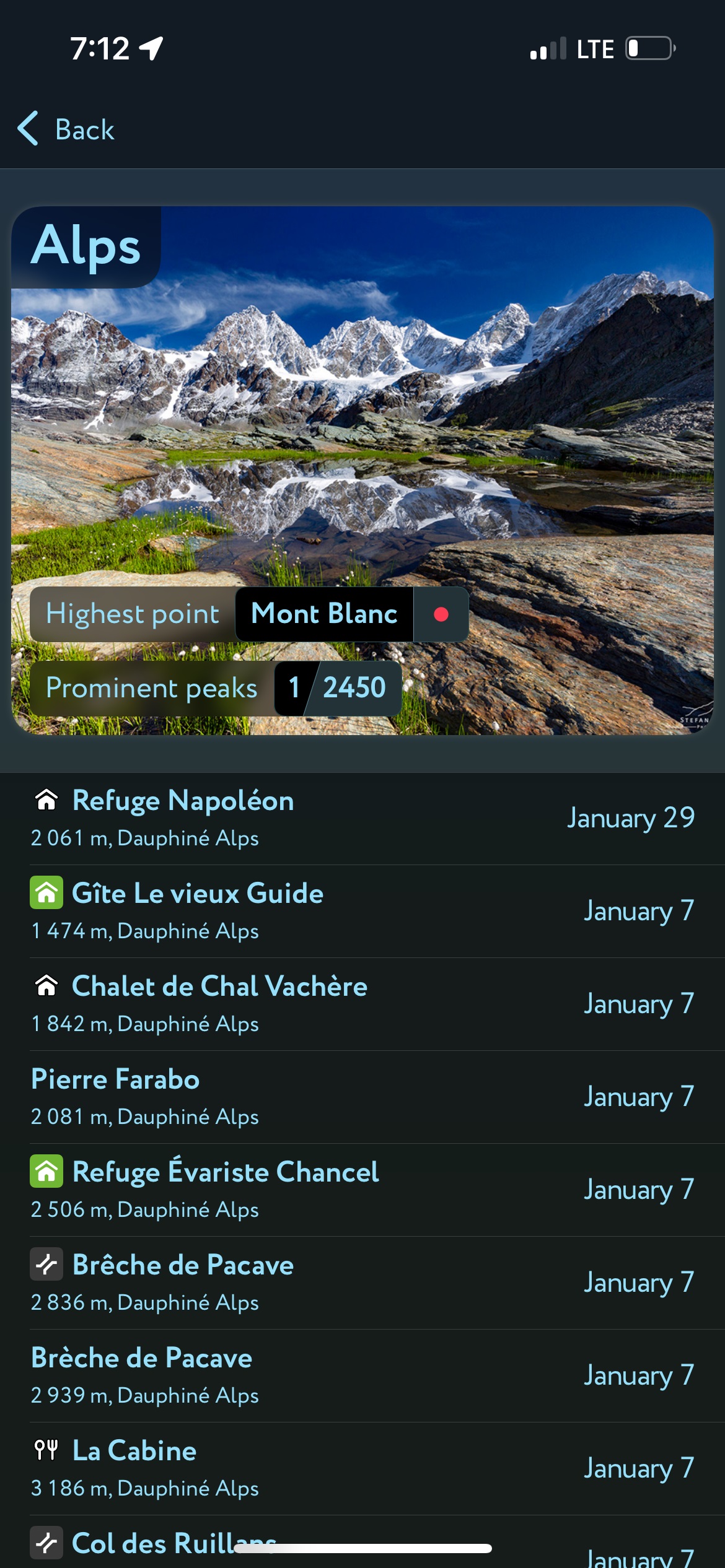

PeakVisor has been a leader in the augmented reality 3D mapping space for the better part of a decade. We’re the product of nearly a decade of effort from a small software studio smack dab in the middle of the Italian Alps. Our detailed 3D maps are the perfect tool for hiking, biking, alpinism, and, most notably in the context of this article, ski touring!

PeakVisor Features

In addition to the visually stunning maps, PeakVisor's advantage is its variety of tools for the backcountry:

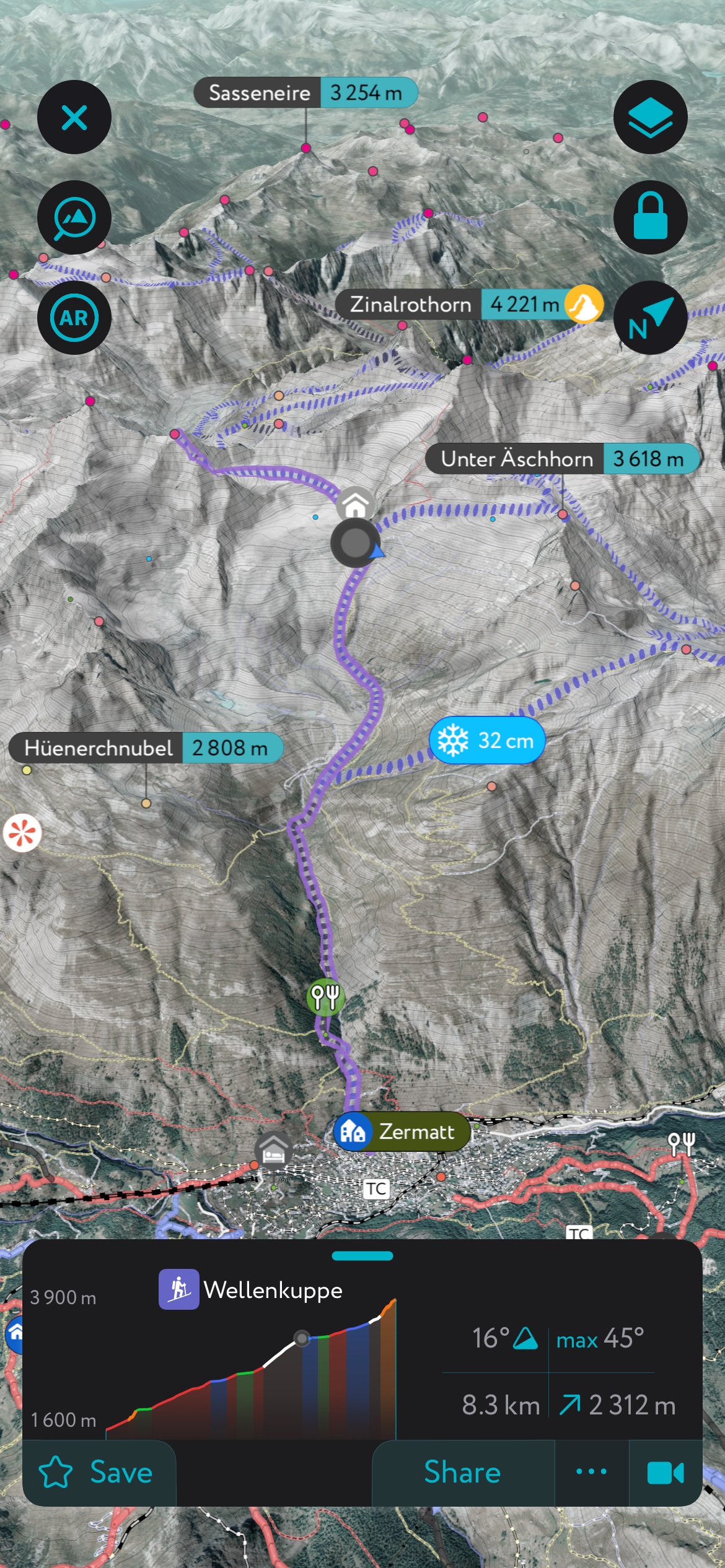

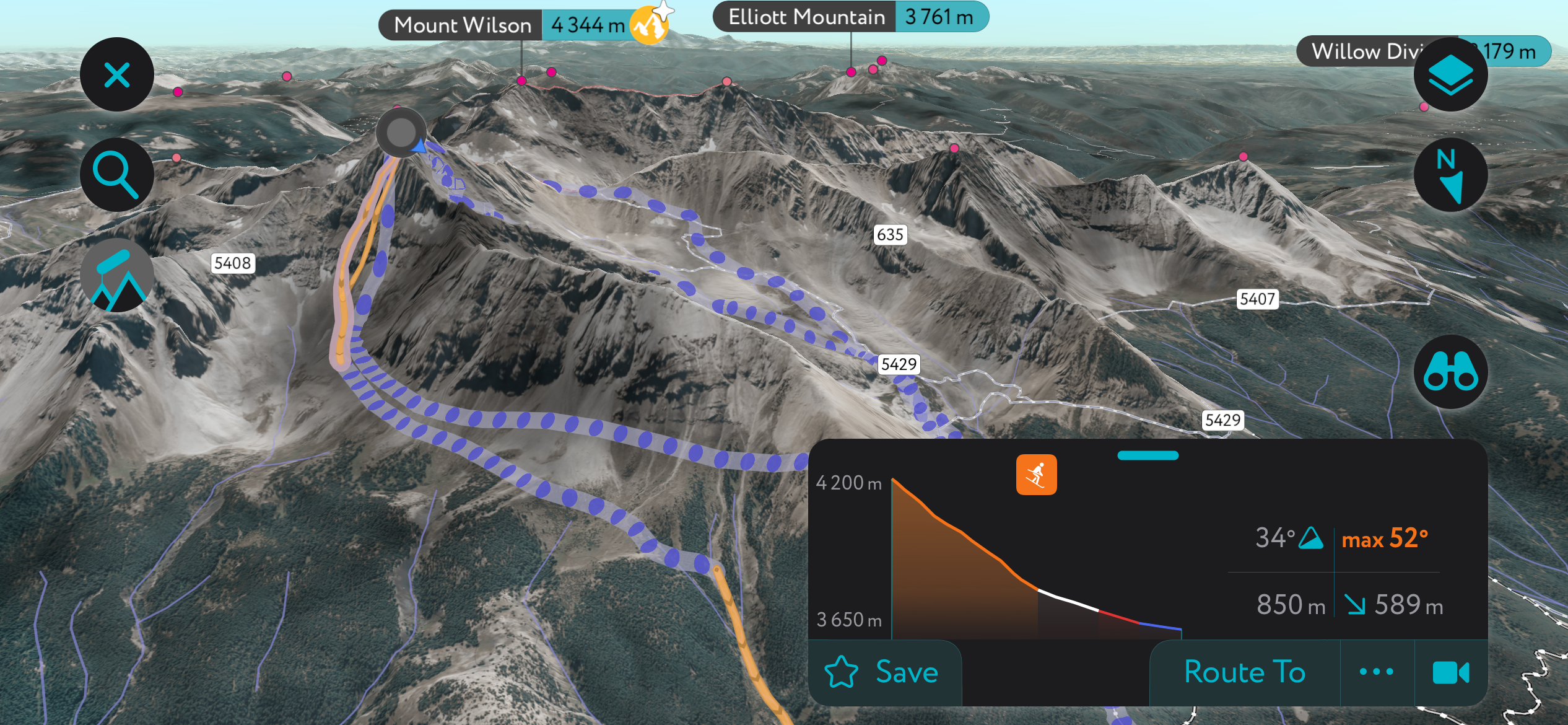

- Thousands of ski touring routes throughout North America and Europe.

- Slope angles to help evaluate avalanche terrain.

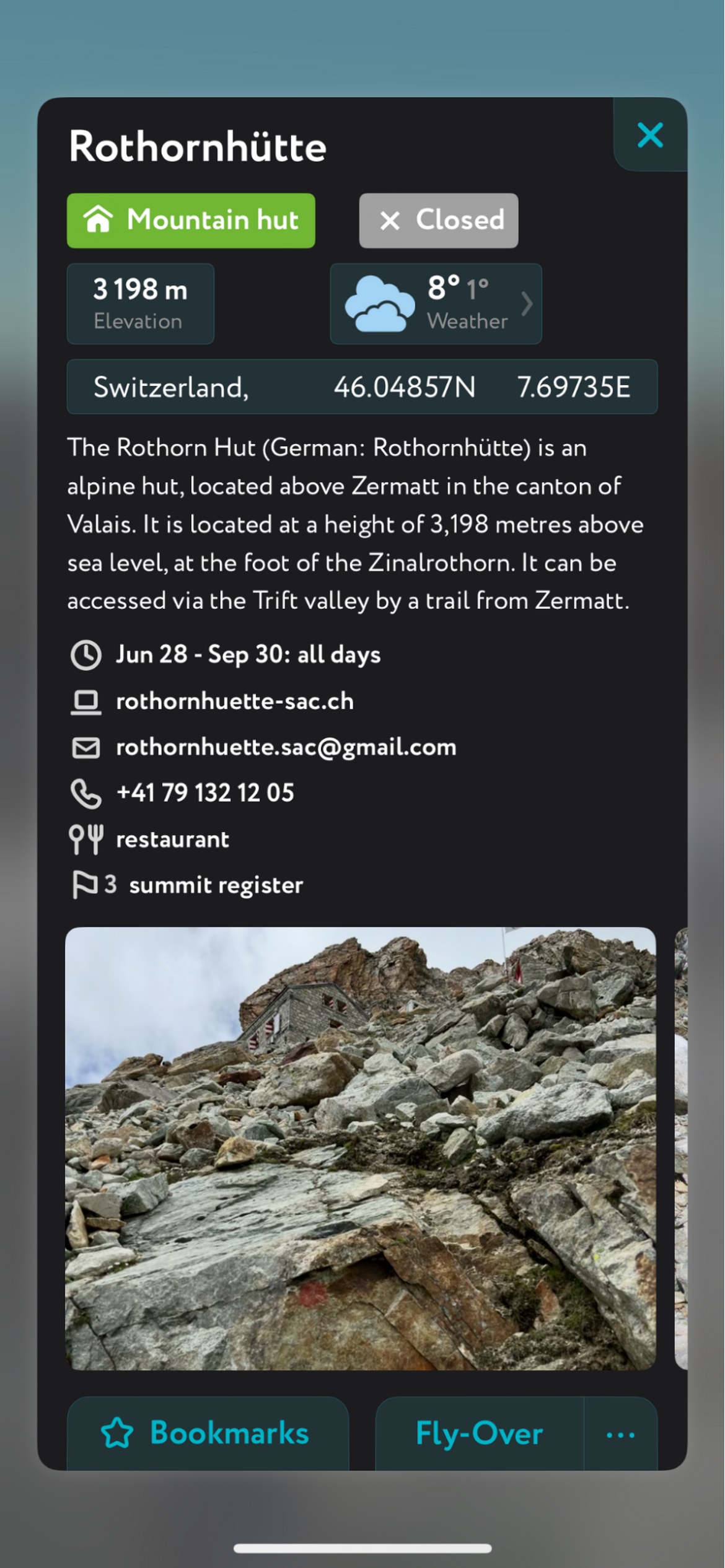

- Mountain hut schedules and contact info save the time and hassle of digging them up separately.

- The route finder feature generates a route for any location on the map. You can tap on the route to view it in more detail, including max and average slope angle, length, and elevation gain.

- Up-to-date snow depth readings from weather stations around the world.

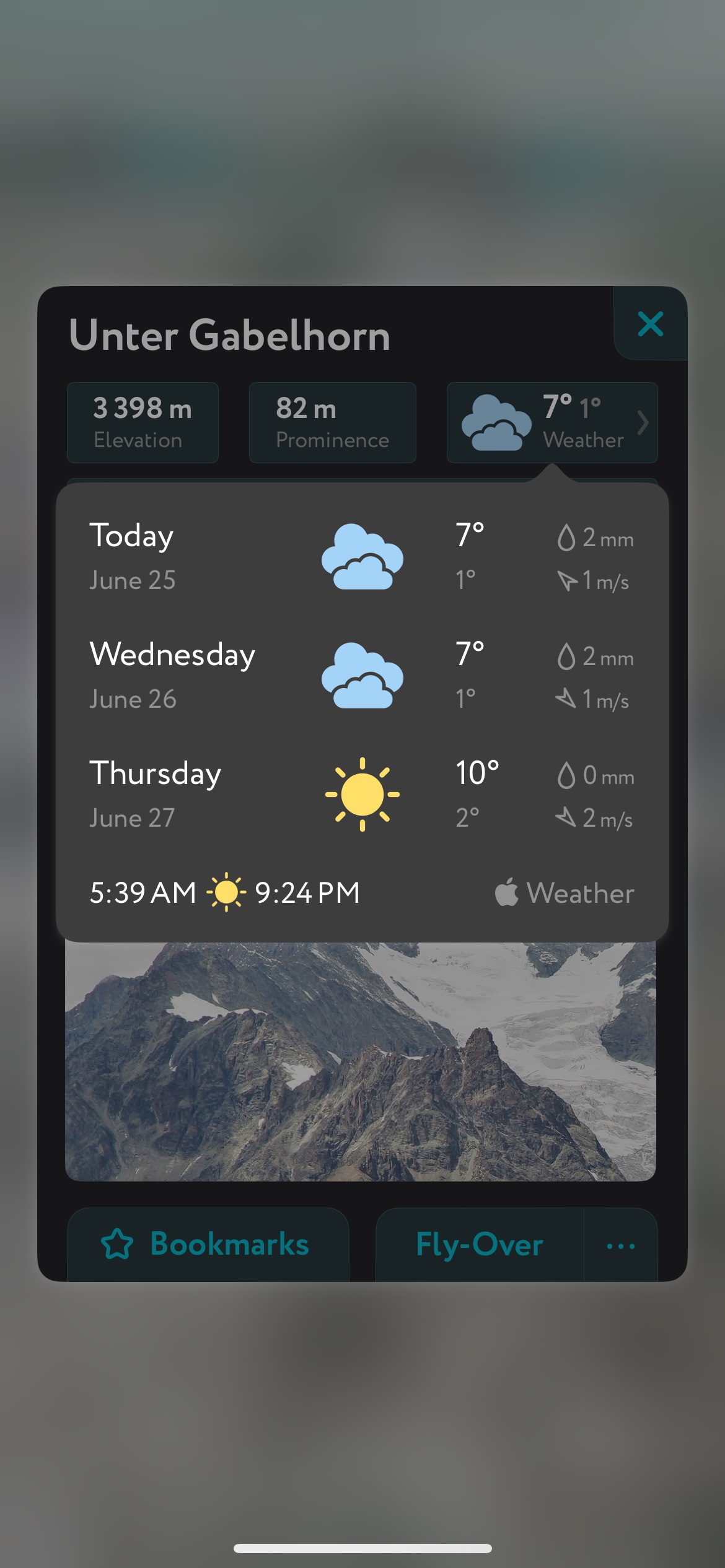

- A point weather forecast for any tap-able location on the map, tailored to the exact GPS location to account for local variations in elevation, aspect, etc., that are standard in the mountains.

- You can use our Ski Touring Map on your desktop to create GPX files for routes to follow later in the app.