France’s Only 4,000-Meter Peak Outside the Mont Blanc Massif

By the time the end of April rolls around, skiing is a distant memory for most folks.

As I returned home to the Écrins range on April 28th, it was spring in the valleys. Passing through Grenoble, the high peaks shimmered in the afternoon sun. The drive up into the mountains had become a tangle of green forest and dense foliage.

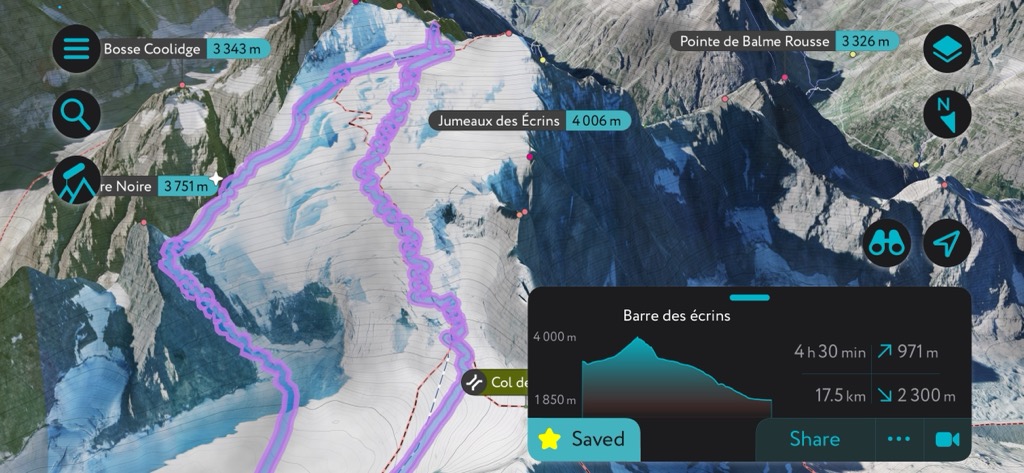

But spring is a fickle friend in the Alps during April, and winter returned that night. A short but sweet burst sifted out 20 cm of light, dry powder over the high mountains. It was time to hit the season’s final objective: the Barre des Écrins (or possibly Dôme de Neige), hitting the classic Barre Noire Couloir on the descent.

The Barre (4,102 m) is the only 4,000-meter peak entirely in the nation of France. Before France annexed the small nation-state of Savoy, it was the only 4,000-er in the country. It’s also the only one outside the Mont Blanc Massif. Most people go for the Dôme de Neige, just next to the Barre. It reaches 4015 m, so it’s still a 4,000-er, though it’s really just a shoulder of the Barre. Anyways, it's not technical (only skinning required in most situations) and it’s immensely popular for those looking to knock off a 4,000-er.

But I’m not much of a box-ticker; mainly, the Barre is just where you go for incredible glacier climbing and skiing in the late spring.

The Approach

I was fortunate enough to have two absolute all-stars on my team, Evert Holma and Filip Rentschler. We set out that night to Ailefroid and camped out between the stars and towering cliffs, some of France’s most legendary multi-pitch climbing routes scattered in the darkness. You could just make out the cliffs in the darkness, illuminated by the brilliant patch of stars overhead.

The next morning, we arose at 6 a.m., drove as far up the road as possible, and hit the trail by 7:30. We were already quite close to Pré de Madame Carle by this point. Fortunately, we had great beta from our friend who had trekked up to the refuge just a few days prior. Taking his advice, we wore shoes for the first two hours, walking on frozen snow and then a steep, rocky trail. Not having to do this in ski boots saved much time and effort.

Finally, we hit snow at about 2,200 meters. Honestly, it was for the best; I wouldn’t relish skinning up the steep summer trail that heads to the foot of the Glacier Blanc. We stashed our shoes along the trail and began skinning along the frozen track with our ski crampons. It wasn’t even 9:30 yet, and the snow was still frozen solid, though the sun was also making itself known in a big way. Since the summer trail faces east, we’d already taken a beating the whole way up.

We quickly arrived at a plateau in the glacial canyon. The Glacier Blanc terminated here just 15 years ago, but had now retreated far up the mountain, though we could still see it poking out. The next pitch, heading to the Refuge de Glacier Blanc, is the only bit of technical skinning to reach the Refuge des Écrins, but it’s not a big deal. Already, the sun had started to soften the snow, and our ski crampons did the rest.

By the time we reached the top of this steep pitch, Mr. Sun wasn’t in a benevolent mood. Whereas we’d had a hearty appetite just 30 minutes prior, the three of us were slightly nauseated by the heat and the climb. It was like being in an oven. Right on cue, we began hearing rumbles, and could see avalanches coming down the cliffs on the opposite side of the valley as the mountain shrugged off its winter coat.

At last, we gained the foot of the glacier. I had hoped for some respite up here, but there wasn’t an ounce of shade to be had on this vast expanse. They say that the mountains make you feel alive, and that’s true; but, in the Écrins, it happens as much through intense discomfort as joy.

I had three sandwiches in my pack, but no capacity to consume them at the present moment. We continued up the glacier—very easy ski touring, mind you—but the sun continued its fitful rage. There were, however, clouds in the forecast, and they finally arrived in time for our final push (a steep 100 m section) up to the refuge. I hadn’t eaten anything and was bonking hard, but the clouds gave me a much-needed boost, and we soon arrived at the refuge.

Depending on where you park on the road, the approach time is about five hours for a standard party traveling at a reasonable pace. If you have to start in Ailefroide, add at least an hour (though, if there’s snow to Ailefroide, there are far better ways of getting to the Refuge des Écrins).

The Refuge des Écrins

We were very early, among the first clients to arrive. It was so warm that I assumed nobody would be starting later, but I was mistaken. Ultimately, it was a busy night, with the 45 or so patrons crammed into two dortoirs and the other two left empty. It always infuriates me how they do this.

After an attempt at a repose, though interrupted by dozens of other guests arriving and dumping their things in the dormitory, I ambled downstairs and fired up a game of cards with the boys. The sun slowly arched to the west, and the common room became drenched in the golden afternoon light. It was a magical few hours.

With several dozen guests, dinner wasn’t quite up to par with my last stay at the Refuge des Écrins, though it was still good. Unfortunately, my night of sleep was among the worst I’ve had in a refuge, which is saying something. In addition to the general discomfort of refuges, I still felt like a boiled lobster from sweating in the sun all day. If you also have trouble sleeping in refuges, I can only commiserate. I cannot not offer any solutions.

The Climb

Frankly, it was a relief when the alarms began going off at 4:45 a.m. for the day’s mission. I wasn’t much in the mood for toast and jam, oats, or corn flakes, the quintessential refuge breakfast, and it was packing up and stepping out into the crisp dawn that revived my soul.

Soul revived, it was time to scrape our way down the steep, icy slope from the refuge, which awakened the senses like a bucket of ice water to the head. The pink glow of early dawn illuminated the Barre in alpen glow. The air was comfortable, though the forecast was for an even hotter day than yesterday, hence the early start.

We hadn’t been able to see the Barre as it had been obscured by clouds the previous day. But now it was making itself known, and I wasn’t impressed with the coverage on the Coolidge Couloir. The Barre Noir, however, looked fantastic and devoid of a single track, unlike the classic route down from the Barre/Dôme, which was checkered with tracks. We briefly entertained the idea of bootpacking up the Barre Noire—avoiding the seracs of the Glacier Blanc, your biggest objective hazard on this climb—but decided that putting in a track through deep snow would be a drain.

We paused at the foot of this great mountain, taking in the scene ahead of us. The seracs are quite active, with blocks of ice littering the slope for hundreds of meters downstream. However, it’s a fairly localized risk; you’re only truly exposed for a few minutes if you move fast. Nevertheless, the three of us had a similar mindset: to push through the next 800 meters as fast as possible. We took a drink, de-layered, and gathered steam for the ascent.

The route is quite apparent. Just weave your way through the seracs toward the upper bergschrund. If you attempt this during clear weather from March to mid-May, it’s almost certain that there will be a skin track and/or tracks already on the mountain. However, it’s not the easiest skinning in the world, and a pair of ski crampons could come in handy, though we didn’t use them.

Naturally, the route passes over some deep crevasses. The glacier was nicely covered when we crossed; some parties roped up, others didn’t. By this time, we were the leading party up the mountain and chose to rope up.

The last headwall is the crux of the skintrack; it was powder snow conditions as we ascended, and we could still feel the icy slope underneath. Without fresh snow, I suspect this area could get quite slippery. Because the glacier is prone to an icy crust underneath the fresh snow, it was a bit of effort to hack in a skin track. Looking back, people began to make it over the initial hump of the glacier and we could see a lemming line of guided parties, the French army, and various other mountaineers.

Toward the top, just before the summit of the Dôme de Neige, we banged a left and continued straight up, hoping to take the arête to the summit of the Barre.

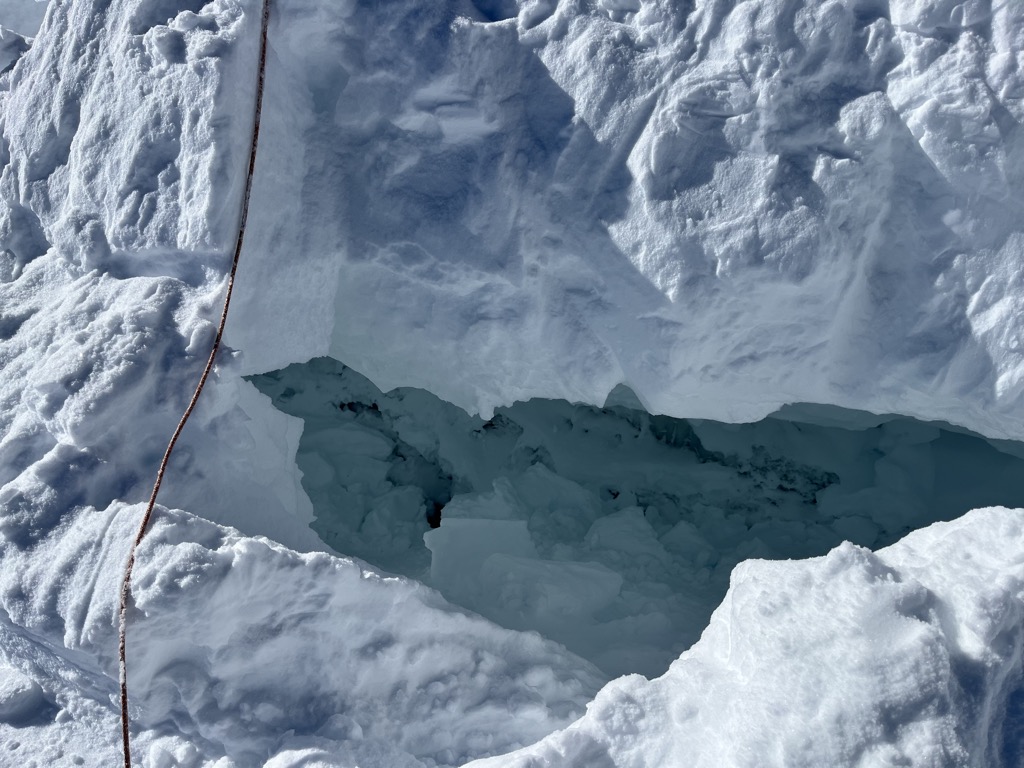

A bergschrund is a type of crevasse that forms at the top of a glacier, where the downward-flowing ice separates from the accumulating ice above, which doesn’t yet have enough mass to flow. The Barre’s ‘schrund stretches the length of the mountain, though it’s less pronounced if you just want to summit the Dôme. We attempted to cross on skis to save the effort of climbing over. Evert floated right over it, but my heavy frame broke right through the snowbridge, and I plopped in. We were still roped up, of course, so no damage done. It was beautiful in the crevasse, a large blue cavern with ice crystals everywhere, like an ornate chandelier.

After climbing out, we transitioned to crampons and the old double ice axe for a steep booter to the arête. All good so far. However, the snow conditions were concerning me. It was very dry and rocky, and the snow had a sugary quality, crumbling off the rocks with little resistance.

When we reached the arête, it quickly became evident that we had neither the time—clouds were building—nor the desire to traverse the rocky arête in ski boots and crampons. It’s not a particularly difficult climb in summer, but it’s formidable when half-covered in snow, not to mention the less-than-ideal footwear.

This is the primary summer route up the Barre, so there were two excellent rappel citations, one equipped with brand new tat and a new piton. We did two 30-meter rappels, and twin 60s would get you down fine and save some time. I was now back below the ‘schrund that I fell into earlier.

Now, the boys really wanted to get to the top, so they decided to bootpack the couloir directly instead of traversing the arête. Instead of crossing the ‘schrund, they stayed above and traversed to the base of the Coolidge Couloir. I decided to pass. I’m a powder skier at heart, I suppose. After seeing the conditions, I was sure it was going to be grim. Lacking summit fever, I transitioned out of crampons and into skis and prepared for my descent.

I was disappointed at how little snow there was on the upper flank of the Barre. We had hoped that the late spring would bring stickier storms to this corner of the mountainous universe. After all, we’d just gotten a meter of super heavy snow that paralyzed ski infrastructure across France. Alas, it was gone with the wind, literally.

The Descent

Unfortunately, while we were busy faffing around on the Barre, a guided party had poached the Barre Noir. To be expected, of course, as it’s an enduring classic steep ski descent. But unfortunate. The silver lining was that having a few tracks along the traverse was helpful for my virgin descent of this beast.

Notably, this traverse involves a section of exposed glacier ice, where you have to point your skis straight for maybe 20 meters. It’s like a little gate-keeping move before you commit to the steeps. Otherwise, you can ski below the serac, but you’ll have to skin or side-step up to get to the couloir. Still, this is a classic link-up and the best way to ski down from the Barre/Dôme.

Besides the glacier ice section, the traverse down to the couloir was on the good side of variable. Stepping up to the entrance of the Barre Noir, you could immediately see how this was a classic.

Being a bit of a snob, I was bummed there were tracks but also secretly grateful that a party had cut the slope. She was good to go. No hesitation. Nobody can deny that solo missions decidedly add a bit of excitement as well.

Two things to note. First, most guidebooks say this couloir is 50 degrees, which may be true at the very top, but it doesn’t feel like 50 for long. Let’s call it 45, which happens to be the perfect angle for skiing. Second, the big crux with this line is the glacier ice that can be exposed, or worse, superficially covered. The exposed ice tends to be on the left side. As a result, people don’t ski this line until spring, when the wetter snow finally sticks.

I watched the guided party clear out of view and gave them a few more minutes. It was time to drop in. The snow quality immediately struck me. The last storm had consolidated into a cold, powdery cushion, with 5-10 cms of powder on top. The very top of the couloir was a bit variable underneath, and I was careful of ice, because a fall here would be consequential, possibly catastrophic.

After the first 50 meters, the bed surface disappeared and the turns became utterly soft, like a mattress pad with a thin layer of powder above. It was on. I made a few large turns and let my slough run before the couloir narrowed. Snapped a quick picture. Then let her loose. The next 60 seconds of powder skiing were up there with the best.

The couloir slowly flattens out into an apron and then onto the glacier blanc, giving an epic conclusion to the run. It’s not the longest, but it’s one of the best coolies out there, and nothing beats the feeling when you soar onto the Glacier Blanc, arching massive turns.

I headed down the glacier and posted up around the beginning of the uptrack to the refuge. I was down by 10:45, and glad for it, because it was getting warm. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a modicum of shade within a square kilometer. I could hear little rockfalls echoing through the valley. The choukas swooped to and fro, searching for food or maybe just to say hello.

After nearly two hours of waiting, I finally spotted the boys coming down from the summit. I knew this was going to be a story; it was only 150 meters of climbing from where we separated, and they had knocked out most of the climb by the time I transitioned and headed down. So I couldn’t figure out what the holdup was.

It turns out that the Coolidge was in extremely bad condition. The bootpack up was sketchy, and the descent required careful sidestepping nearly the whole way. Still, they were lucky the clouds had chosen not to form on this day because that would have been even worse. Feeling vindicated that I made the right choice, we took a drink and continued down.

I wasn’t too stoked on the wait, but it generated an unexpected reward: epic corn conditions heading down the Glacier Blanc. The glacier is pretty flat, but after the refuge, it gradually steepens. Skinning up, I hadn’t even considered how good it would be, but it was shattering glass all the way down.

We made massive sweeping turns, jumping over little undulations, and hooting and hollering the whole way. Everybody had stayed left, away from the center of the glacier. Unlike the rest of the tour, there wasn’t a track to be seen. We would’ve surely done it again if we weren’t an extreme combination of tired, hungry, and dehydrated.

To my surprise, the rest of the skiing was on point as well. I expected a sticky mess, but I suppose the low humidity and overnight freeze from the glacier worked in our favor.

With excellent skiing, it only took a few minutes to get from our meeting place high on the glacier to the snowline at about 2,200 meters. We uncached our shoes, and getting those ski boots off sure was sweet. We descended the summer trail until we reached the valley filled with not-so-frozen snow. So little did we want to put our ski boots back on that we traversed on foot, occasionally post-holing into knee-deep snow.

Passing by the Refuge du Pré de Madame Carle, the doors were, incredibly, open wide. Usually in France, things are fermature exceptionnelle when you expect them to be open, but this little hut was ready for business. Within minutes, three large beers were sitting on the table, served by a kind gentleman who was very excited to hear about the adventure.

The mountains love superlatives, and, happy to say, that beer was one of the best I’ve had. The tension of a big climb and descent melted away, and my body seemed to dissolve into the wicker chairs we sat on. When it came time to wrap up and finish post-holing the last kilometer back to the car, I barely noticed my soaking wet shoes.

And that sums it up, my friends. What a way to cap the season. I was disappointed not to have made it up the Barre, but super stoked with the snow conditions on the descent. Of course, shout-outs to Evert and Filip for being great friends and partners.

Thanks for reading and stay safe out there.

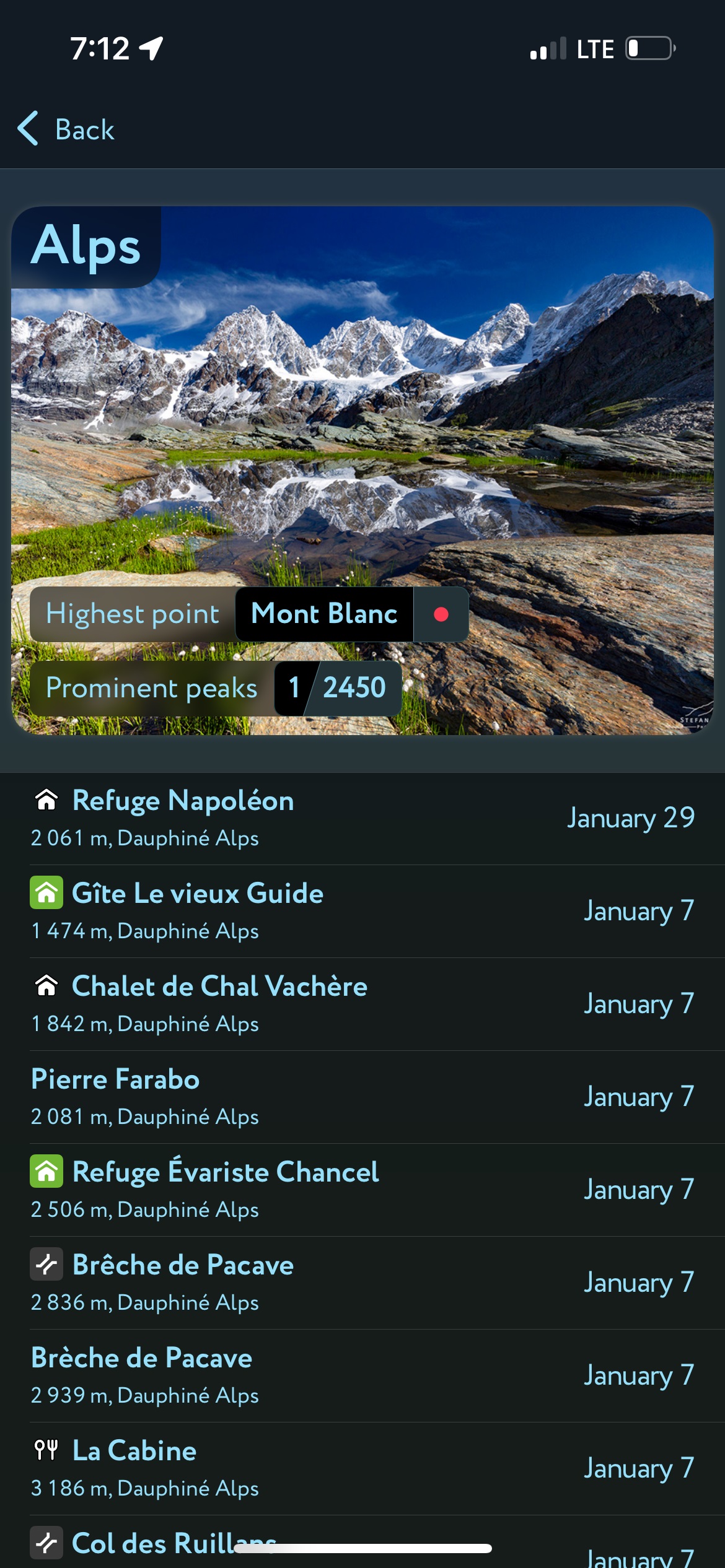

Using the PeakVisor App

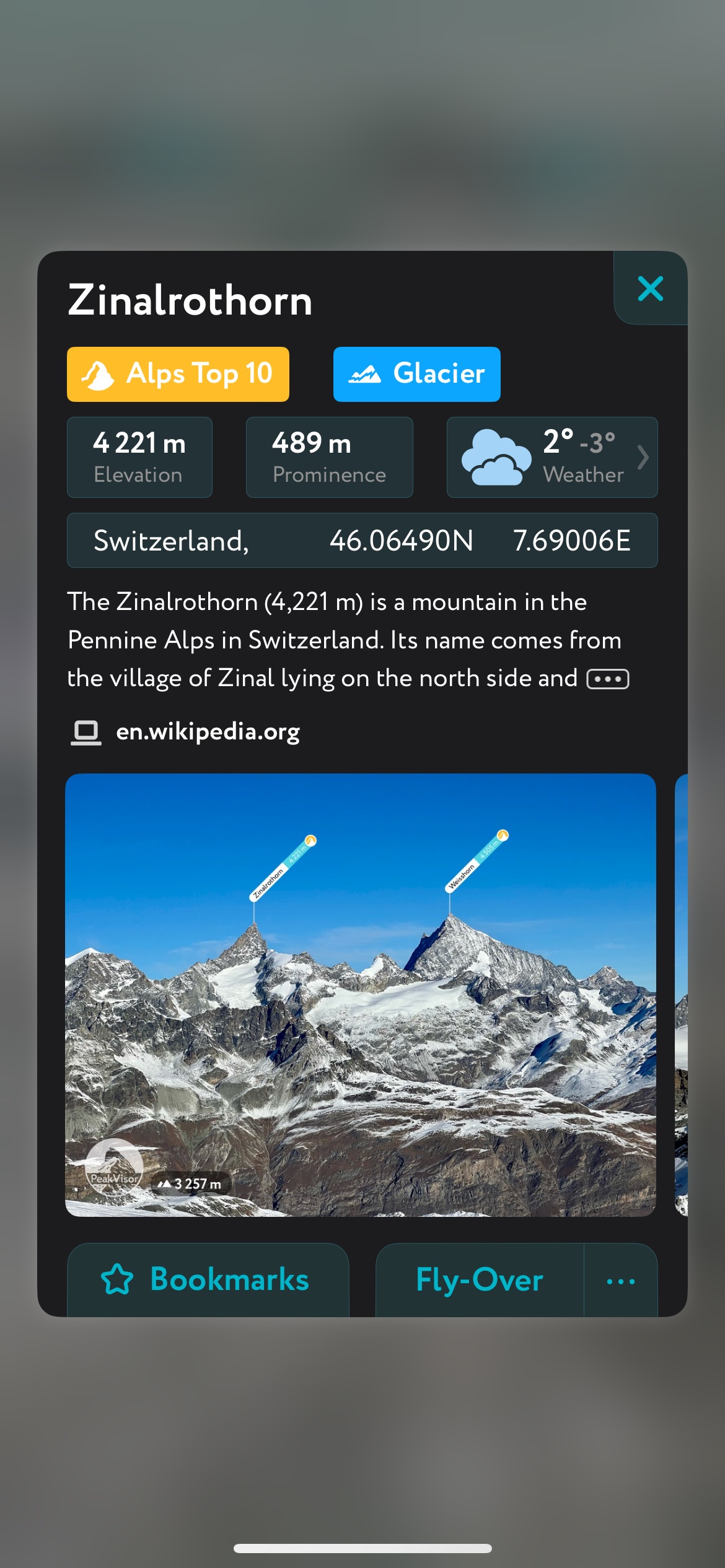

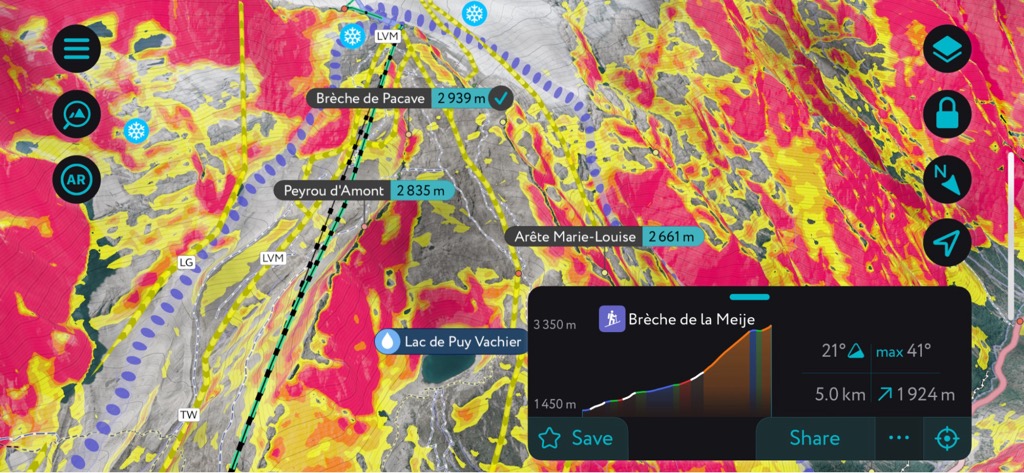

Interested in skiing? Check out the PeakVisor App. PeakVisor has been a leader in the augmented reality 3D mapping space for the better part of a decade. We’re the product of nearly a decade of effort from a small software studio smack dab in the middle of the Alps. Our detailed 3D maps are the perfect tool for hiking, biking, alpinism, and, most notably in the context of this article, skiing!

PeakVisor Features

In addition to the visually stunning maps, PeakVisor's advantage is its variety of tools for the backcountry:

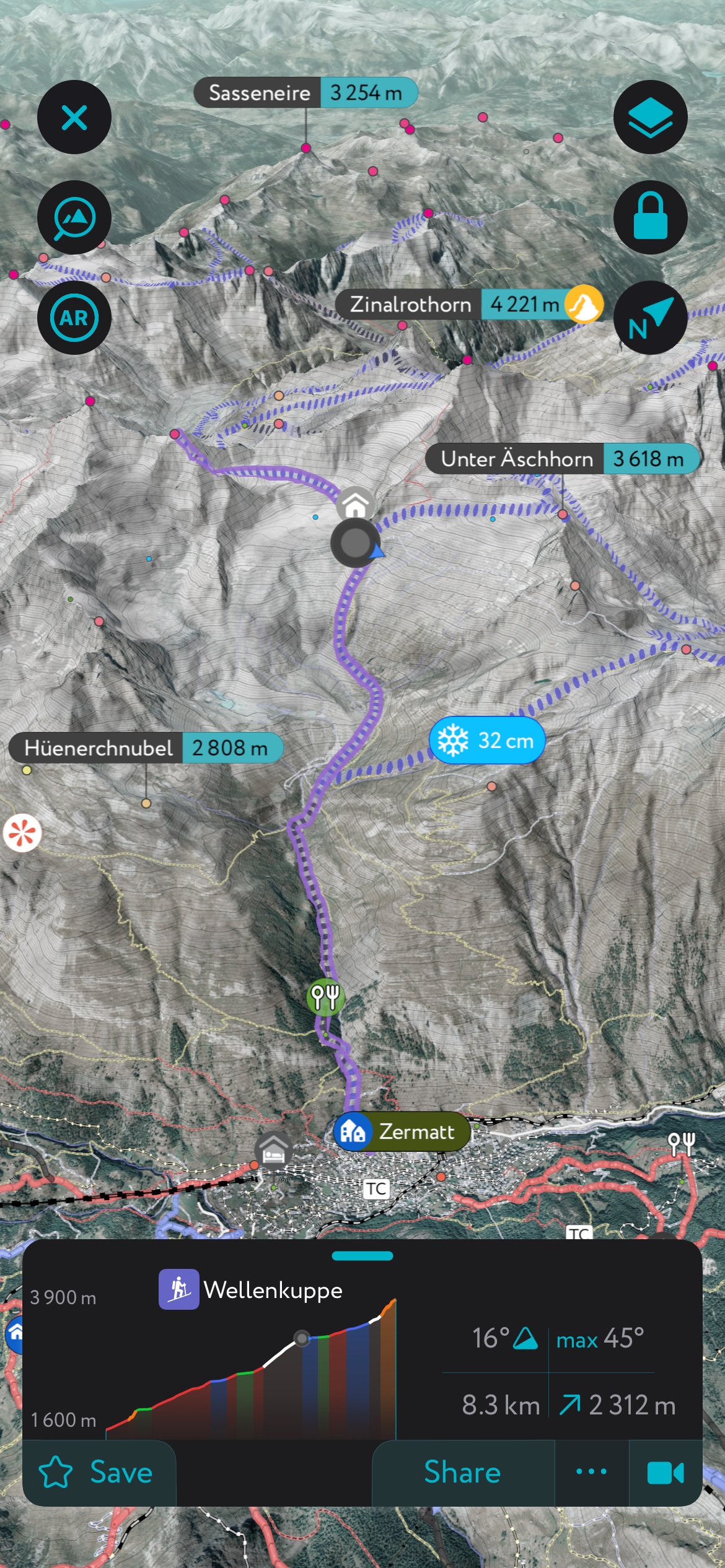

- Thousands of ski touring routes throughout North America and Europe.

- Slope angles to help evaluate avalanche terrain.

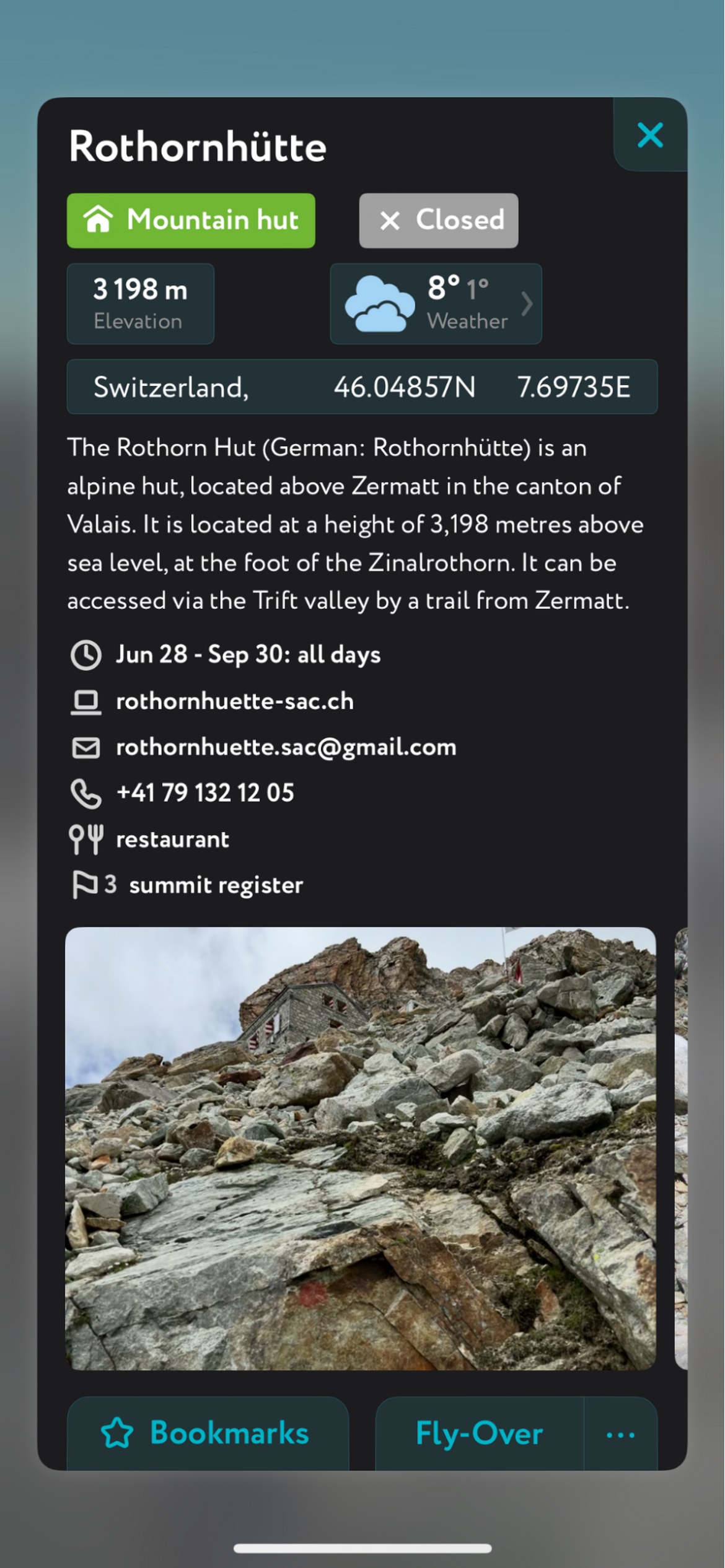

- Mountain hut schedules and contact info save the time and hassle of digging them up separately.

- The route finder feature generates a route for any location on the map. You can tap on the route to view it in more detail, including max and average slope angle, length, and elevation gain.

- Up-to-date snow depth readings from weather stations around the world.

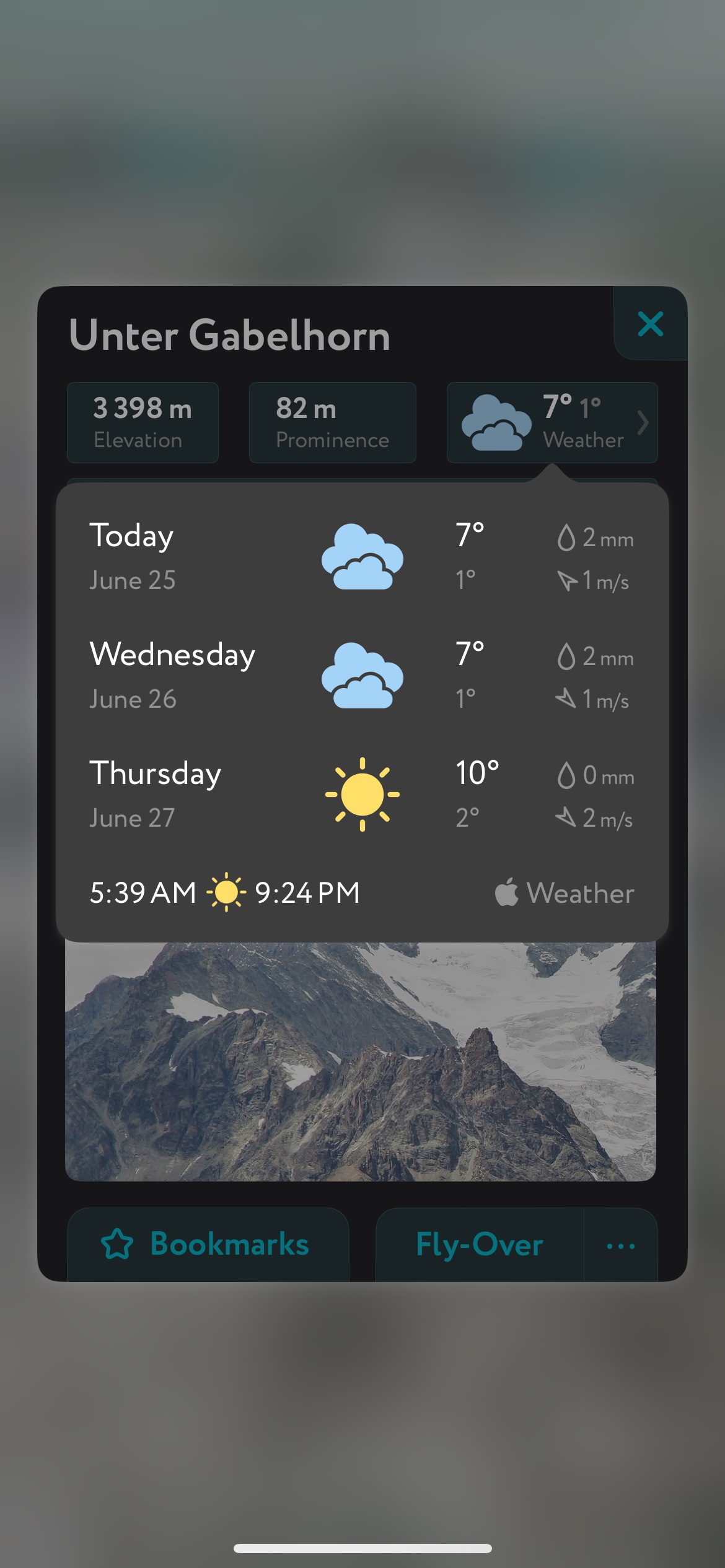

- A point weather forecast for any tap-able location on the map, tailored to the exact GPS location to account for local variations in elevation, aspect, etc., that are standard in the mountains.

- You can use our Ski Touring Map on your desktop to create GPX files for routes to follow later in the app.