A Thru-Hike Trail Guide

A Thru-Hike Trail Guide

The Long Trail, or “LT,” as it’s affectionately known, is not just any old long trail. It is America’s oldest long-distance hiking trail, conceived on Stratton Mountain in 1909 by James P Taylor, Headmaster at the Vermont School for Boys at the time.

As the story goes, while poring over maps in his tent, waiting for the morning mist to clear, a vision of a primitive trail cutting through the dense forest, traversing the ridgelines that form the spine of the Green Mountains, came into view.

The footpath would weave, playfully, in and out of the state’s most curious topographical features, up and over its highest peaks, and right through the many wilderness areas between Southern Vermont and the Canadian Border.

The following year, 1910, the Green Mountain Club (GMC) formed, and planning and construction of the LT was underway, starting with the notoriously rugged terrain connecting the Camel’s Hump and Mount Mansfield regions.

After 20 years of sweaty trail building, dogged determination, both public and private support, and plenty of elbow grease, the last section of trail, from Jay Peak to Journey’s End, Canada, was completed in 1930.

Finally, a proper end-to-end hike on the LT was achievable, with many takers up for the challenge right from the get-go.

Today, the Green Mountain Club has grown to well over 10,000 members, who serve as stewards of what many consider Vermont’s most important resource and link to its natural heritage. Remarkably, throughout the 115 years since its beginnings, the LT has remained relatively “unimproved,” staying true to its roots and Taylor’s early brainchild.

“Hike Your Own Hike”

One of the many charms of Vermont’s Long Trail is how approachable it is for long-distance hiking. Sure, that 272 miles (438 km) of often steep, sometimes muddy, and typically rocky New England trail isn’t going to hike itself. But on the other hand, most relatively fit people who enjoy backpacking can complete the trail in 3-4 weeks. Enough time to really immerse oneself in the wilderness experience, find a daily hiking routine, and enjoy an extended stretch in the wilds of Vermont. But not so long that you must rearrange your life to complete it in a single push.

Compared to the long-distance trails that would follow in the LT’s footsteps, the Appalachian Trail (AT), Continental Divide Trail (CDT), and Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) are each thousands of miles long. They cross deserts, carrying over multiple seasons, and sometimes necessitate long road walks that piece trails together. Meanwhile, the LT is literally just a walk in the woods.

One speedy traveler hurriedly completed his self-supported LT End-to-End hike in just 5 days, 11 hours, and 34 minutes, earning himself the Fastest Known Time (FKT). To each his (or her) own, but both the Green Mountain Club and the author encourage end-to-enders to savor the experience and travel at a comfortable pace, if possible. In other words…Hike your own hike!

If you’ve ever fantasized setting out on a backcountry trail with nothing but the contents of your backpack and the boots on your feet, to experience the freedom and adventure of long-distance hiking, (and all the joy, suffering, blood, sweat and tears that go with it,) you might find the following inspirational. If you’ve done this kind of thing before, it could just be the next trail to add to your bucket list. Either way, I assure you, it’s a worthy one.

The LT: Division by Division

The LT is partitioned into 12 trail divisions, each with its own individual landscape, unique character, and challenges that test hikers, physically, mentally, and otherwise.

The 272 miles of the proper Long Trail are marked with 2” x 6” white rectangle blazes. It shares these trail markings with the AT throughout the entire first 100 miles (Divisions 1-5), starting at the Southern Terminus.

Double blazes often mark important turns, while intersections are typically marked with signs, though not always.

The LT’s 88 side trails, totaling 166 miles, are marked with blue blazes of the same shape and dimensions and comprise the rest of the Long Trail System. These spur trails typically traverse the LT, leading to trailheads and other notable points, like lookouts, peaks, ponds, or shelters.

Division 1: Massachusetts-VT State Line to VT Route 9

Division 2: VT Route 9 to Stratton-Arlington Road

Division 3: Stratton-Arlington Road to Mad Tom Notch

Division 4: Mad Tom Notch to VT 140

Division 5: VT 140 to U.S. 4

Division 6: U.S. 4 to Brandon Notch

Division 7: Brandon Gap to Cooley Glen

Division 8: Cooley Glen to Birch Glen

Division 9: Birch Glen to Bolton Mountain

Division 10: Bolton Mountain to Lamoille River

Division 11: Lamoille River to Tillotson Camp

Division 12: Tillotson Camp to Vermont Border

*For the purposes of this article, trail descriptions start at the Southern Terminus of the LT, located at the Mass/VT border, and continue North to the Canadian border, the Northern Terminus of the LT.

The Southern Terminus of the LT can be accessed in one of two ways, via the Pine Cobble Trail or the AT. Either approach makes for an excellent warm-up, as it’s 1700 vertical feet (530 meters) up to the start of the LT.

The full LT gains about 66,000 total vertical feet (20,000 meters) of elevation, which is like climbing Mt Everest twice, starting at sea level, but without the need for supplemental O2, a good weather window, eighty thousand dollars, or a full-blown expedition.

Division 1: Massachusetts-Vermont State Line to VT Route 9

The 14 miles that make up Division 1 are by far the shortest division of the LT and probably the mellowest. They’re wide, well-marked, and easy to follow from the start. The trail is void of any notable terrain obstacles to navigate at this early stage, making it ideal for working out any gear issues and dialing in systems.

The first mountain that NOBO LT hikers tackle is the aptly named Peak 3025, the high point of the division. The trail crosses several brooks and streams, some of which have bridges, while others require rock hopping to keep your boots dry.

From a geological perspective, the Southern Green Mountains of Vermont are ancient, with orogeny dating back roughly 350 million years. The granite that makes up the southernmost part of the range is considerably older, at 960 million years. These once regal mountaintops have since been worn down by the effects of erosion and the most recent series of ice ages, to the low, rounded, gentle summits we see today.

Northern hardwood forests are prevalent at elevations below 2,400 ft, both in Division 1 and throughout Vermont. Flora at this lower elevation generally consists of the VT state tree, the sugar maple, as well as American beech and yellow birch. Fewer numbers of white ash, hemlock, and white cherry trees mix in. Vermont is renowned for its flaming red, yellow, and orange foliage displays in the late Fall, and these hardwood forests are the reason why.

The understory is covered in a dense layer of decaying leaves, where ferns, hobblebush, and moose maple dominate the scene. In the heart of summer, these plants will overwhelm every nook and cranny of the low-elevation forest and contribute to the legendary Green Tunnel that Vermont’s Long Trail is known for.

The final peak in this stretch is Harmon Hill (2325 ft / 709 m), which offers a fine vista of the bucolic countryside and the pastoral town of Bennington.

The backside of Harmon Hill is an absolute beast of a descent. Here, the LT winds down a steep granite staircase to the road crossing at VT Route 9.

Division 2: VT Route 9 to Stratton-Arlington Road

Division 2 starts with a steady climb up from the road crossing to Maple Hill. Following several easy climbs and descents through rolling terrain, the LT enters a balsam and spruce swamp. The trail here, and in many boggy and marshy sections along the way, is crossed on elevated wooden planks called puncheon. These boardwalks protect the fragile marshes while keeping hikers above the muck, but can prove slick and treacherous in wet conditions.

Climbing back up to the ridge, the LT begins ascending Glastonbury Peak (3748 ft / 1142 m), where the mix of flora begins to tilt in favor of the spruce/fir forest at the higher elevations, closer to treeline. Frequent lookouts are a welcome diversion in the dense hardwood forest.

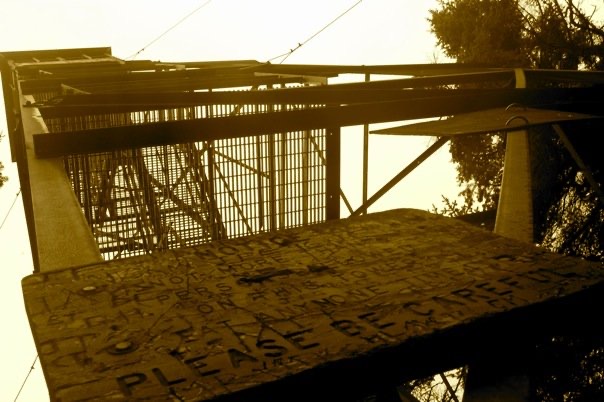

The high point of Division 2 is the Glastonbury Fire Tower, built in 1927 and more recently restored to its original splendor. It offers astounding 360-degree panoramic views of the Berkshire and the Taconic Ranges, considered among the finest in Southern Vermont.

The LT continues to follow the ridge on more rugged terrain and at mid-elevation, through transitional forests, providing access to several overnight sites with backcountry cabins. These wooden structures vary in size, shape, and age. While some are very basic, some of the older structures are quirky or eccentric, adding to the lure.

In rainy or otherwise inclement weather, these cabins can be a wonderful shelter from the storm, which has surely led to many “zero-days” over the years. The trail crosses numerous rock features and boulders, along with creative trail-building solutions through rugged sections of trail, which keep things interesting as the LT continues to slowly ramp up in difficulty.

Division 3: Stratton-Arlington Road to Mad Tom Notch

The LT’s Division 3 takes hikers up and over the first iconic peak of the journey, Stratton Mountain, where both the LT and the AT were both conceived in the early 1900s.

At an elevation of 3996 ft, the wooded summit of Stratton falls short of alpine terrain, so the best summit views come from the superb fire tower lookout on the south peak of Stratton Mountain. From this vantage point, hikers are treated to sweeping vistas of the surrounding landscape, including Mt Equinox and, on a clear day, Killington Peak, the next major objective on the northbound route. A spur trail takes hikers to the north summit of Stratton Mountain, the first of many ski resorts hikers encounter on the LT.

Beyond Stratton Mountain, the LT descends nearly 1,500 ft to Stratton Pond, the largest body of water on the trail. It is also the location of the single busiest overnight campsite on the LT, making erosion and damage to the fragile ecosystem a problem due to overuse. Fires are prohibited here and on some other popular overnight locations on the LT. For this reason, you should bring a camp stove for cooking and boiling water, as fires may not always be an option.

Following Stratton Pond, the trail maintains its elevation and is positively cruiser for the next 10+ miles before ascending to Bromley Mountain, home of a fun, but small south-facing ski resort and yet another fire tower near the summit. This is also excellent wildlife viewing terrain, and I was lucky enough to spot a young female moose through the mist one morning after leaving the Bromley War.

Division 4: Mad Tom Notch to VT 140

After crossing Mad Tom Notch, the LT enters the Peru Peak Wilderness—the first of six total wilderness areas hikers will encounter on an end-to-end hike—and climbs steadily up and over Styles Peak and Peru Peak. Throughout this section and other wilderness areas that follow, the trail is less frequently blazed, narrower, and has a more remote feeling. Hikers should expect to walk a little longer between white blazes.

The next mountain on the route is Baker Peak. It has a modest elevation of 2,850 ft that belies its exposed granite ledges and sporty ridgelines that make for a fun summit scramble.

In inclement weather, there is an alternate route to avoid the exposure and slick rocks. Following a long descent, the LT reaches the Big Branch bridge, which can make for excellent swimming when conditions are optimal.

A short, blue-blazed spur trail leads to White Rocks Cliffs, and at just .2 miles, it proves a sweet side-trip for its copious quartzite outcrops, rock spires and cairn gardens, a virtual new-age art installation in the woods.

Flora and fauna remain consistent with the previous divisions, while northern hardwood forests continue to define the landscape. In portions of the trail cresting 2400 ft, the setting maintains its transitional forest zone, where fir and spruce join the maple, birch, and beech trees,.

Wildflowers are plentiful, particularly in the Spring, as later in the season the taller, leafier, moose maple and bristle berry tend to hide smaller plants from the sun and limit their growth.

Birds, including hermit thrush, veery, and chickadee, add birdsong to the mountain air. White barred owls remain ever-present, yet rarely seen. Closer to water sources, bogs, and swamps, amphibians like red efts and wood frogs are constant companions throughout the hiking season.

Division 5: VT 140 to U.S. 4

The LT climbs up from the road crossing and then descends once again into the green-cloaked Clarendon Gorge. A suspension bridge crosses Mill River here, before some undulating terrain gives way to a full-on climb up Killington Peak (4235 ft / 1291 m), part of the Coolidge sub-range, and the second highest peak in the state.

Killington is a major ski resort and remains busy throughout the summer. The resort offers thru-hikers free access to the gondola; however, if timing allows, the better option is to bag the peak via the short Killington Peak spur trail, as the LT proper does not top out on the summit. This is the first chance to get above treeline and into the alpine zone, with big views of Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains of New York State to the West.

Just beyond the spur trail for Killington Peak, nestled at treeline, is the wood and stone Cooper Lodge, the highest shelter on the LT. After side-hilling the west side of Pico Peak without summiting, the LT passes through lovely conifer forests and the Pico Ski Resort, before descending through spectacular white birch forests and to the road crossing that completes this division.

Division 6: U.S. 4 to Brandon Notch

Just barely into Division 6, the LT reaches an important milestone and crossroads, mile marker 100, AKA, Maine Junction at Willard Creek. Here, the AT makes a right turn toward the White Mountains of New Hampshire and eventually, Mount Katahdin, where it reaches its Northern Terminus. LT continues north (left) along the prominent Green Mountain ridge.

The LT maintains an elevation of around 2,000 ft to 3,000 ft throughout the entire division, with the occasional short climb and descent, while somehow managing to steer clear of any summits. Three quality lean-tos are located along the trail.

Moving forward, the trail becomes noticeably more rugged as it continues through the Green Mountains, Central and Northern Vermont, and ultimately, the Vermont-Canada border.

Division 7: Brandon Gap to Cooley Glen

Throughout this division, the LT sticks to the long, forested ridgelines above 3000 feet. Along the way, hikers summit six peaks, offering up capacious views along the way. We are not in the training grounds of Southern Vermont anymore; the burly Northern Vermont peaks loom in the distance.

Water is hard to come by on the ridge, here and elsewhere, so it’s best to plan accordingly, as there are few reliable sources. After traversing the wooded summits of Mt. Horrid, Gillespie Peak, and Worth Mountain, the LT makes its way onto the cut ski runs of Middlebury College’s Snowbowl.

The trail descends to the low point of the division at Middlebury Gap, and following a quick climb, enters the remote and lightly maintained Breadloaf Wilderness, an area with generally fewer hikers and trail improvements, making it a favorite for hikers seeking a far-away feeling.

There is a steep climb to the summit of the Wilderness’ namesake peak, which is the high point of the division at 3835 ft (1169 m). At the upper elevation of this division, the LT spends more time in the coniferous transition zone from about 2500 ft to 3500 ft, where red spruce, balsam fir, and paper birch are increasingly common, while the hardwoods begin to drop off and fade away. Club mosses and lichens pepper the understory of these enchanted forests, clinging to boulders and the oldest trees. As the soil is more acidic at this elevation, flora is somewhat limited, but always mystical when present.

Wildlife around this elevation is diverse and widespread, including whitetail deer, chipmunk, raccoon, red fox, squirrel, porcupine, moose, and black bear. Typically, black bears are not aggressive towards humans. However, there are over 5,000 bears in the state, and more humans than ever. There have been incidents; backpackers are required to either hang a bear bag with their food or use a bear-proof container throughout their time on the LT.

Although Vermont’s last catamount, also known as a puma or mountain lion, was allegedly killed in the late 1800s, there have been many sightings recently. These are likely lone males migrating back from the expanses of wilderness out west, often in search of a mate. It’s unknown if there are any breeding pairs.

Division 8: Cooley Glen to Birch Glen

As the LT goes up and over Mt Abraham at 4006 ft (1221 m), technically the south peak of Mount Lincoln, the LT enters the alpine zone for the first time. This is the domain of fragile and rare tundra flora, including purple crowberry, bigelow sedge, diaspensia, alpine sandwort, and bearberry willow, many of which also exist in the Arctic Circle.

Hikers will also pass through wind-stunted alpine spruce and fir trees called Krumholtz, which can be hundreds of years old, yet only a couple of feet tall. In some places in the world, this type of alpine vegetation is abundant. However, in the relatively low elevation Greens, this is only one of three zones where these tundra plants grow. These are protected species in Vermont, and traveling on durable surfaces (trail) in the alpine is the standard.

The vistas reign supreme from the alpine summit of Mt. Abe, as imposing views of the White Mountains to the east, the Adirondacks to the west, and much of the Greens to the north and south stretch out in all directions.

The LT next traverses Sugarbush Ski Resort, and the wooded summit of Mt. Ellen, which ties with Camel’s Hump as the 3rd tallest peak in the state at 4093 ft (1,248 m). The trail between Mt Abe and Mt Ellen is top-notch, high-elevation ridge hiking, with plenty of ups and downs to test the legs of weary hikers. Without a doubt, this is some of the most fun terrain on the LT, best experienced on a warm, sunny day.

Shortly after walking over the trails of Sugarbush, the LT continues to the next ski hill, Mad River Glen, known for its steep, expert, skier-only tree skiing and slogan, “Ski It If You Can”.

Beginning at Lincoln Gap, and extending to the Winooski River in the next division, the LT is known as the Monroe Skyline, named after the creator of this section of trail.

Division 9: Birch Glen to Bolton Mountain

Climbing out of Huntington Gap, the LT summits three peaks in succession on the way to Camels Hump, making for a lot of vertical gain and some premier hiking terrain on the ridge.

Camel’s Hump, with its namesake, one-of-a-kind summit profile, is not only (tied for) the 3rd highest peak, but it’s also the tallest undeveloped peak in the state and a definite highlight of Division 9. The summit is home to rare alpine vegetation, some of which is included on the VT endangered plant list. It is also one of the most popular peaks in the state.

From the Camels Hump summit, views are astounding, particularly of the Winooski River Valley below., which drains into Lake Champlain. It’s all downhill from here, as the longest descent of the LT is next. The trail drops more than 3k vertical feet to Jonesville, at 326 ft, the low point of the LT.

Upon ascending back to the ridge, hikers are treated to views of Camels Hump to the southeast that are, quite simply, unparalleled. Looking forward, several west-facing lookouts are available with views of Lake Champlain and the Adirondacks as the Division closes out at the summit of Bolton Mountain.

Division 10: Bolton Mountain to Lamoille River

Every section of the LT is special, yet the 30 miles (50 km) that comprise Division 10 are on another level. The LT stays mostly above treeline as it traverses the Mount Mansfield 4393 ft (1339 m) summit, the highest point in Vermont, and the most extensive alpine zone in the Greens.

The Mount Mansfield summit is rambling, with terrain features named after the summit’s profile, which resembles a man’s face, including the Chin (the true summit), Forehead, Nose, and Adam’s Apple. The peak is home to Stowe Mountain Resort, which has plenty of infrastructure below treeline, while the summit is adorned with a massive radio tower.

Unannounced storms are common above treeline, not to mention dangerous, due to the threat of lightning strikes. It’s wise to complete this section in calm, clear weather. If that is not an option, alternate routes around the mountain stay below treeline. There are also several escape routes to exit the ridge quickly during a severe weather event; however, these can be dangerous in their own right when slick.

In dry weather, the side trails off the Mansfield summit are truly remarkable, dishing out terrain unlike anything in the State of Vermont, or anywhere, for that matter. This is the most rugged and technical hiking in the state, and exploring the different aspects of the mountain and spur trails is highly recommended.

A personal favorite is the Wampahoofus Trail, named after a mythical creature whose body has evolved for easier side-hilling. The trail approaches the Forehead of Mt Mansfield from the south and winds between tight rock features and caves, before surmounting a wild rock overhang resembling the open jaws of the Wampahoofus.

Back on the LT proper, after taking hikers up and over the Chin, the trail quickly sheds elevation as it drops 2500 vertical feet into the rocky, primordial Smuggler’s Notch, a highway mountain pass and location of a local’s ski resort. Of all the miles of the LT, these are easily some of the most inspiring, as the trail winds in and out and over craggy terrain with frequent cliffs, gulleys, and glacial erratics that create a natural playground that is quintessentially Northern Vermont.

Moss and lichen cling to anything they can, including the oldest spruce and fir trees that dominate this section’s flora. Along the way, the LT passes the high elevation, Sterling Pond, before scaling Sterling Peak, Madonna Peak, Morse Mountain, and finally Whiteface Mountain. A lengthy descent to the Lamoille River valley closes out Division 10, which truly deserves to be experienced firsthand, as words can only do it so much justice.

Division 11: Lamoille River to Tillotson Camp

Climbing out of the Lamoille River Valley, the LT offers some of the smoothest trail on the route, with a mostly easy grade, summiting two smaller peaks.

Hikers then conquer three peaks in succession as the LT traverses Laraway, Butternut, and Bowen Mountains, passing through majestic hemlock and hardwood forests. The LT then descends into the gnarly Devil’s Gulch, traversing jumbles of large boulders and continually rugged terrain, making for challenging travel with a loaded backpack.

After climbing back up to the Belvidere Saddle, through steep ravines, crossing old stone walls covered in moss, the landscape forms the lush, unadulterated Northeast Kingdom. The trail forks off to either of the two Mt. Belvidere summits, while traveling through scenic spruce and fir forests, mossy bedrock, and other gnomish oddities.

Division 12: Tillotson Camp to Vermont Border

Having come 249 miles from the Massachusetts border, NOBO hikers have just 23.3 miles to reach the Northern Terminus. However, it’s no gimme, as the LT serves up back-to-back grueling climbs and descents. This time it’s Haystack Mountain, down to Hazen’s Notch where the LT cuts through several steep ravines, before ascending Buchanon Mountain, which all top out around 3,000 ft (900 m).

The LT sticks to the rugged ridgelines as it approaches the highpoint—and highlight—of Division 12, Jay Peak (3786 ft / 1153 m). Jay is the last of an astounding 12 ski resorts that the LT brushes up against on the trek. The trail takes hikers up and over the summit, through cut ski runs, snowmaking pipes, and snow fencing.

Despite its lower elevation, this far north, the summit is sparsely wooded, and the views expand in all directions, stretching south to Camel’s Hump on a clear day, and the first and only views into Canada’s Sutton Mountain Range.

The end is near, but there are still mountains to climb! The trail continues, steeply at times, up and over Doll Peak, followed by several smaller peaks, before the LT casually terminates at Journey’s End, a small, unremarkable clearing just beyond the Canadian border, marked with a statue to commemorate the Northern Terminus.

Trip Planning for the Long Trail

Planning for a thru-hike on the LT will vary greatly depending on your backpacking experience, risk tolerances, lifestyle, age, and style. Regardless, there is no better way to get the wheels in motion than to start weighing your options (and gear)!

Best Time to Go

Although conditions vary season to season, it’s generally best not to go too early in the spring or too late in the fall, to avoid cold temperatures and wintery conditions…unless that’s what you’re after, of course.

The Green Mountain Club kindly requests that hikers avoid the LT during “mud season” (typically before Memorial Day and after November 1) to protect the trail surface and tread, which is especially subject to damage this time of year. A common rule of thumb is that if you have to repeatedly walk around the trail to avoid mud, it’s time to turn back and hike elsewhere.

The trail is officially closed in the upper regions of Camel’s Hump and Mount Mansfield, two of the more heavily travelled, fragile, alpine zones along the trail, during mud season. But mud is not the only factor to consider.

Between late May and early July is black fly season. If you are familiar with the species, you already understand this is not merely an inconvenience but a veritable barrier between you and your sanity. If not, consider yourself warned.

Mosquitos are present most of the summer, so no matter when you hike, it is wise to carry a head net to give yourself some relief, as both species can be insatiable and unbearable at times.

By late July, and through mid-September, the Green Mountains are generally pleasant and ideal for long-distance foot travel, with plentiful wildflowers, songbirds, and lush green hardwood forests greeting hikers with open arms. Of course, mountain weather and conditions can change without a moment’s notice, and Vermont is known for its fickle weather conditions.

Northbound (NOBO) or Southbound (SOBO)?

Most hikers who attempt an end-to-end hike each year do so as NOBO travelers. However, plenty of hikers have thoroughly enjoyed going against the grain for various reasons. If you’re getting a late start in the season, where cold temps and winter weather could impact your travel, it could make sense to get the Northern section completed ASAP and hope the weather is milder in Southern Vermont (as it typically is.)

One advantage of starting at the trail’s Southern Terminus is that the mountains are lower and gentler, and gradually gain in elevation as the LT heads north. This allows NOBO hikers to build their fitness, get their trail legs under them, and work up to the taller and more challenging peaks in Central and Northern Vermont.

Overnight Shelters and Camping

One of the unique and special aspects of the Long Trail is its abundance of overnight shelters. Along the 272-mile trail, backcountry travelers will find a generous 54 shelters, generally spaced out every few miles. It’s is a considerable advantage in inclement weather. It can be challenging and frustrating to set up or break down a tent during a downpour, which is inevitable at some point.

Most LT shelters are of the lean-to variety, which is a basic, 3-sided wooden structure with a roof, a platform floor and, in some cases, bunks for sleeping. A lean-to will provide a buffer from rain and snow, and possibly the wind, if its direction is favorable during your stay. They will not, however, give you any respite from the mosquitoes or black flies. Mice are perpetual residents around these structures, and one should anticipate their presence and plan accordingly.

Other, more refined overnight shelters exist on the trail, including camps and lodges, fully enclosed structures with doors and windows, some of which are truly works of rustic art (mice also live here).

Overnight shelters are a great way to meet other hikers and find some community on the trail, whether hiking alone or with partners. If you’re seeking solitude, you may luck out and score a shelter for yourself on occasion, but you shouldn’t count on it.

Regardless of what shelter or camping area makes sense for your next overnight on the trail, keep in mind that shelters are first-come, first-served, and at busy times may be fully occupied by a troop of Boy Scouts, a college orientation, 12 smelly thru-hikers, or something else you could never anticipate. This is particularly important during the first 100 miles of the hike, where the LT runs concurrently with the AT, and the trails share overnight shelters (and everything else). Shelters are typically less crowded once the AT breaks off to the east at Maine Junction.

For this reason, among others, thru-hikers are strongly urged to carry a tent. You also may prefer the solitude of a quiet night in your tent, or come up short on miles and not want to hike in the dark to reach the next shelter, etc. A tent can also keep the bugs at bay when nothing else will do the job.

Food Supply

One of the biggest decisions one will have to make prior to a thru-hike on the LT is whether to mail food drops in advance or resupply along the way. The bottom line is, if you are planning to be in the woods for three weeks, a resupply will be necessary. Only you can decide where, what, when, and how, but carrying roughly five days’ worth of food is a good happy medium for many. Results may vary.

The LT crosses many roads along the way, some of which are a short hitchhike to a local town with a convenience store, grocery, post office, hotel, and/or hostel.

Hitchhiking is common in and around the trail towns that the LT passes nearby and can be a good way to resupply on food, stay in a quaint VT Bed & Breakfast, grab a proper shower, pick up an essential item, or grab a hot meal during a storm. Of course, not every thru-hiker cares to indulge in such luxuries during their journey. If you do choose to hitchhike, trust your best judgment and do what feels right.

Another reason you may want to get into town is to retrieve a food package you mailed ahead to yourself. This is a common approach to resupplying for people with food restrictions or specific indispensable items that may be unavailable to resupply along the way. Post Offices in trail towns along the way will usually hold USPS packages for hikers and some local businesses will also accept packages, although prior arrangements must be made in most cases.

All things being equal, it is probably more straightforward and enjoyable to resupply as you go. It’s hard to say what you will be hungry for while hiking all day, every day, so resupplying as you go offers more flexibility. Not to mention, many of the towns near the LT are hiker-friendly, quaint, and beautiful as can be. In persistent stormy weather, a town trip can be an enjoyable diversion from the Green Tunnel.

Water Sources

While many water sources, like rivers, lakes, and streams, are located on or near the LT, some are more reliable than others. Water is scarcer in the Northern LT and along ridges and in the alpine. Availability will depend on the time of the season, so it’s crucial to plan accordingly and carry extra water for drinking and cooking through potentially drier sections.

Some hikers have successfully completed the LT without filtering or otherwise treating their water, although this is strongly discouraged. Most LT hikers use a water filter or other method for treating their water before drinking, as Giardia is real and will hamper your enjoyment at the very least or send you home packing at worst.

Yes! There are composting outhouses, known as privies, on the LT, and they are located near overnight sights and maintained by GMC caretakers. Be sure to say thanks!

As always, hikers should be familiar with Leave No Trace principles and be prepared to follow them.

The GMC publishes an annual edition of “The Long Trail End-to-Ender’s Guide,” an invaluable resource for a thru-hike on the LT, complete with information on services near the trail, a mile-by-mile log, details on shelters, and much more.

Every year, around 100 hikers complete an end-to-end thru-hike on Vermont’s Long Trail. It’s not for everyone, but it’s an experience I will always cherish.

Happy Trails!

Using the PeakVisor App

At PeakVisor, we love information. That’s why we write articles like this one.

While we always recommend a backup paper map, the world is becoming an increasingly digital place, and having a good map on your phone makes everything easier. Check out the PeakVisor app for 3D maps, and record your trek across Vermont with our tracking features to share later with your friends.

It doesn’t stop there; we have even more information on thousands of additional hikes, ski tours, and ski resorts across the world. In fact, we’ve compiled information on all publicly maintained walking tracks worldwide, formatted onto our 3D maps.

Each division of the Long Trail is on the PeakVisor app. You can also upload .gpx files if we don't already have a trail on our servers. The PeakVisor app is available for iOS and Android; give it a shot and discover our visually stunning 3D Maps, adding a new dimension to your adventures

Other PeakVisor Tools

PeakVisor started as a peak identification tool—you’ll have noticed the photos throughout this article—but we’ve evolved into purveyors of the finest 3D maps available. We continue to expand our offerings. You can track your hikes directly on the app, upload pictures for other users, and keep a diary of all your outdoor adventures.

Most recently, the PeakVisor App has included up-to-date weather reports, including snow depths, at any destination. We've also been hard at work adding the details of hundreds of mountain huts, including information on overnight accommodation, dining options, and opening hours. You can also use our Hiking Map on your desktop to create .GPX files for routes to follow later on the app.