Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

- Temperature

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

La Grave. Even the name is scary, as it shares the same letters in the same order as the English word grave. In French, the word grave doesn’t have such deadly connotations. Instead, it merely means serious. With this in mind, we can indeed say that La Grave est grave.

The sleepy cluster of villages known as La Grave is perched in a deep valley that demarcates the north end of the Parc National des Écrins. There is one lift, ‘the Téléphérique,’ to 3200 m (10,500 ft), and another drag lift to 3600 m (11,811 ft). No trails exist on the mountain; every descent is off-piste and requires a high level of skiing and route-finding. Here, we trade groomed, manufactured runs for natural features such as couloirs, bowls, and faces.

The Téléphérique was constructed in the ‘70s, allowing hikers to go up and look around at the Glaciers de la Meije and boost the economy. In the ‘80s, pioneers began exploring the steep slopes on skis. The ‘90s and ‘00s saw a popularization of extreme skiing and increased traffic in La Grave. Yet, the village remains authentic, and the slopes are still relatively empty.

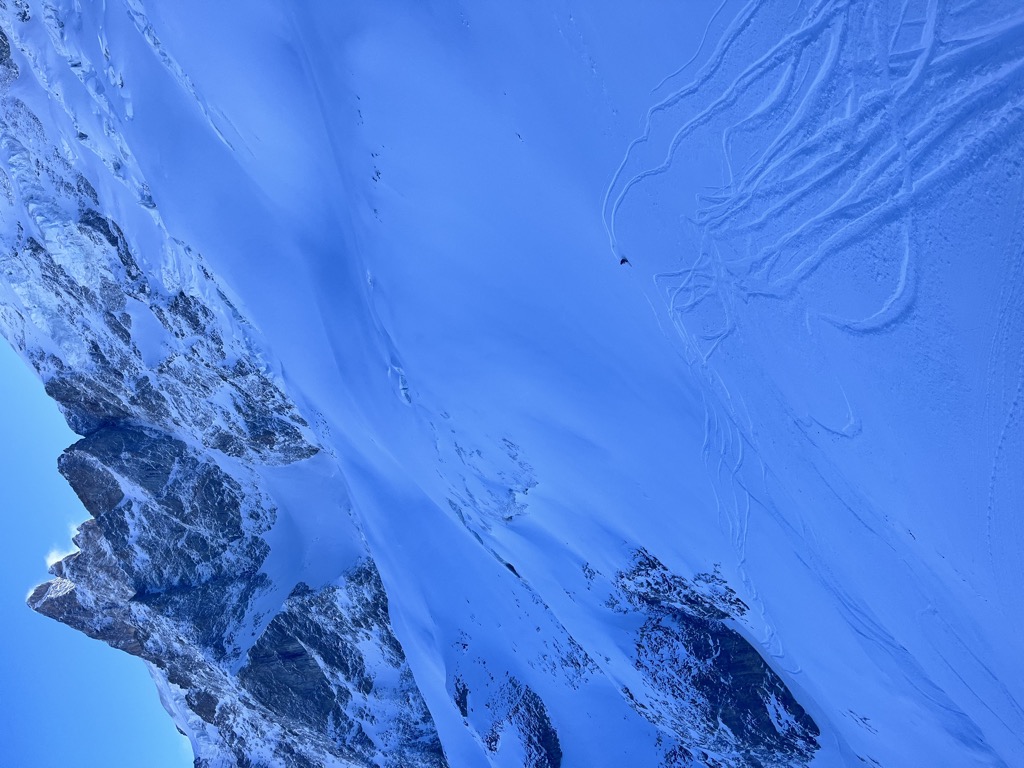

La Grave is a land of extremes. First, there's the ski terrain, much of which could be considered extreme. However, I believe the spectrum of possible experiences here defines La Grave’s extreme-ness. At a ski area that has less than 100 skiers most days, you might wait in line for hours at the inefficient lift on a March powder day. While temperatures on the glacier can often threaten frostbite in minutes, I’ve never sweated so hard while skiing as I do while threading my way down 2000 vertical meters of off-piste. I’ve skied the best and worst terrain of my life and had the best and worst snow conditions of my life (sometimes on the same run). Most of the time, La Meije shows us her infinite love. But sometimes, she is trying to kill us.

No luxury accommodations exist in La Grave. There are no nightclubs or cinemas. The village offers but a few restaurants, gear shops, hotels, and a small market. Even the slightest injury on the mountain necessitates a helicopter rescue if you cannot ski down. It’s not everybody’s cup of tea, but this place rules for those serious about their skiing.

The purpose of this guide is to share some of the knowledge I’ve accrued over the past few seasons at this hallowed ski area. The mountain commands respect; a sense of humility and a thirst for knowledge are essential here. Hopefully, this article can serve as a practical guide to some and a more comprehensive introduction to others.

La Grave is located in the southeastern French department of Hautes-Alpes, approximately one hour west of the Italian border and one and a half hours east of Grenoble.

La Grave is directly on France Route 1091. In the summer, it’s a parade of RVs, sports cars, motorbikes, and road cyclists through town. In the winter, there is far less traffic but far more hazards. The road surface is often covered in snow and ice, and it’s not uncommon to see rock fall along the way.

La Grave, located at 1450 m (4,757 ft), is a straight shot from Grenoble, which hovers around 200 m (660 ft). The drive ascends 1.2 km directly upwards over 80 km (50 mi); the climate morphs from Mediterranean lowlands to alpine larch forests, with views of cascading glaciers. Sometimes there’s a guardrail…sometimes there’s not. It’s not a drive for the faint of heart, nor will it be easily forgotten. Bring snow chains in the winter; they might come in handy. You can reach La Grave from the town of Briançon, just 39 km (24 miles) to the east.

One of the best ways to reach La Grave is to take the LER 55 bus. It departs twice daily from Briançon → Grenoble and Grenoble → Briançon. It’s inexpensive and makes about a dozen stops in all the different mountain towns.

All of the standard rules for the Western Alpes apply here. Geneva and Milan are the best airports for international flights, while Turin, Grenoble, and Lyon may have regional flights from Europe that work well.

The La Grave ski season lasts from around the third week of December (anywhere from Dec. 16th to the 23rd) until May 1st.

Ski touring can start as early as November at the nearby Col du Lautaret. Lift-access skiing is available at the beginning of December at several regional resorts, including Les Deux Alpes, Alpe d’Huez, and Serre Chevalier. These resorts eventually shut their door in mid-to-late April, while La Grave stays open, with the Téléphérique spinning until May 1st.

Some years, the resort could stay open until June with plenty of snow cover, though they stop running the lift; you must rely on your own two feet to power up the mountain. Les Deux Alpes, just on the other side of the massif de La Meije, stays open in the summer for glacier skiing. In La Grave, folks will ski on the glacier once the lift opens back up for bike park season if the conditions allow.

“Variable” is the word that best describes the snow conditions in La Grave. As I’ve mentioned, the mountain has been host to both the best and worst snow conditions I’ve ever skied, sometimes in the same run. Snow conditions have generally been worsening over the past couple of decades, especially over the past few years.

Nevertheless, you can find enjoyable snow on almost any given day somewhere on the mountain if you know where to look. The mountain has several advantages, including its high elevation, north aspect, and abundant snowfall from many directions. Thus, La Grave is likely to be one of the last ski resorts standing in France as climate change continues to ravage the ski industry.

You’ll probably read on the internet that La Grave has no avalanche control. Technically, that’s true. However, it’s not as if you can just go up on the mountain whenever. A “commission des guides” consists of the patrouilleurs and several mountain guides who go up the Téléphérique each morning after fresh snow. The guides ski down and assess the conditions, ultimately deciding whether to open the mountain.

One massive advantage to this is not having bombed-out avalanche debris all over the prime slopes like at other ski resorts. The obvious downside is that ski-triggered avalanches do happen. Needless to say, you need to be prepared with a kit and basic avalanche awareness.

La Grave’s early season is less certain than other ski areas, mainly because the terrain requires quite a bit of snow coverage. Since there are neither pistes nor snowmaking, there is an utter reliance on nature to deposit the meter or so of consolidated base layer snow needed to cover the classic routes effectively. However, thin coverage is the only disadvantage to December in La Grave.

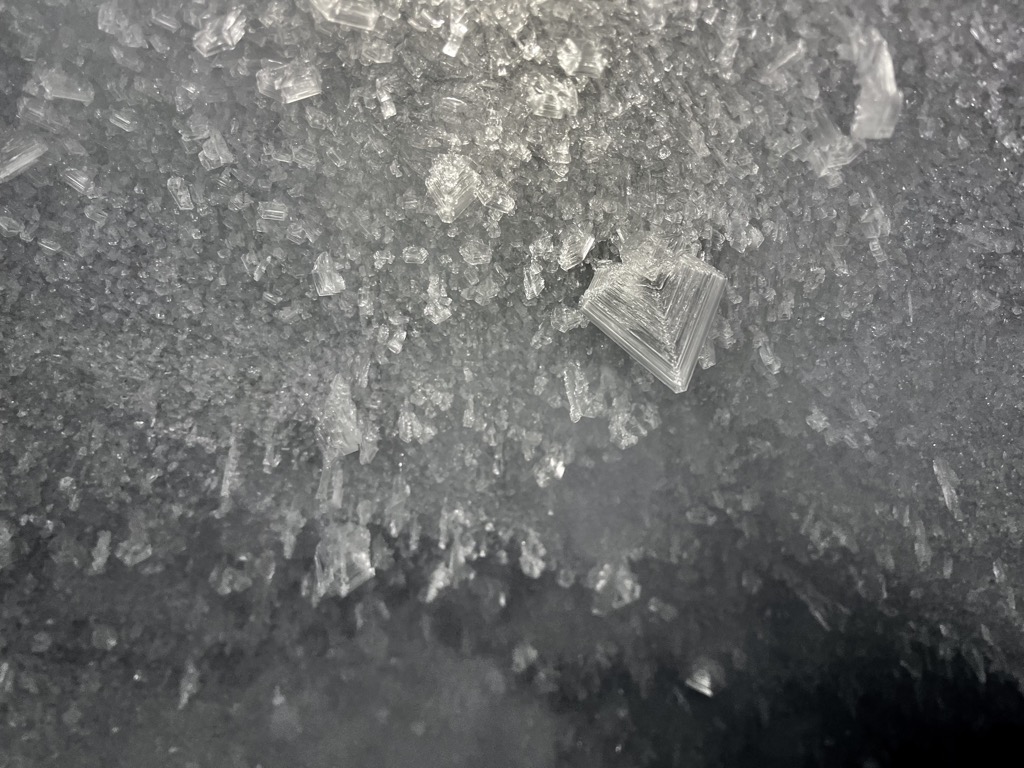

Personally, I love December (and January) due to the lack of crowds and the fact that the mountain gets zero sun during this time, ensuring cold snow conditions, even days or weeks after a storm. December can be stormy (two of my four Decembers in the French Alps have been very snowy) with plenty of powder days; just watch out for powder sharks hidden beneath the snow.

Unfortunately, if you’re visiting from afar, the uncertain December snowpack makes this period too risky to plan a trip around.

January is locals’ month at La Grave. Usually, coverage is good enough to ensure ample skiing on the classics, snow conditions are excellent due to a complete lack of sun effect on the mountain, and the crowds have yet to arrive. Moreover, January tends to be snowy in the French Alps; all four of the Januarys I’ve spent here have been snowy, especially in relation to the rest of the season.

Although it tends to be drier, February is likely the second-best month in La Grave, averaging snow conditions and skiable terrain.

As February progresses, the sun's angle increases and begins to creep over La Meije, drenching the mountain in heavenly light. The juxtaposition between the sun and shadows is yet another example of La Grave’s tendency toward the extreme. Where shadows reign, the mountain's contours hibernate in a cold blue light. Meanwhile, the sun brings brightness unique to high-mountain, glaciated environments; glacier glasses and dark goggle lenses are recommended.

February is still cold, and thus, the sun does not fully transform the snow as it does in late March and April. Rather, it gently softens the chalky slopes and offers better visibility.

Storms roll through, albeit with less frequency than at other times of the season. High-pressure and sunny days often define February in the French Alps. It’s as if winter needs a breather between the snowier early and late seasons.

February tends to be crowded in the French Alps because the French vacation takes place during this time. You can expect increased traffic during this time, although it’s not as bad as at more family and piste-oriented resorts like Les Deux Alpes.

March is classically the best month for La Grave and big-mountain skiing in the Alps generally. The mountain receives plenty of sun, and the visibility enhances the skiing without baking the snow as much as in April and May. The coverage is usually at its seasonal apex; most itineraries are usually skiable during this time, although the window for the “road runs” (more on these below) is diminishing.

Best of all, March tends to be a snowy month in the French Alps. There have been several good storm cycles in all three Marchs I’ve spent here. The snow falls on a good base, so it doesn’t take a monumental storm to have monumental conditions.

March is also the busiest month at La Grave. It’s when the international skier elite set tends to descend on the resort. Watch out for bluebird weekend powder days during this month; you could spend most of your day waiting in an extraordinary line at the Téléphérique, which is not designed to handle more than a few hundred skiers at a time.

The Alps sit at 45-47° North latitude, and Grave is one of the Alps’ highest-elevation ski resorts. As a result, April can be a heavenly month despite the increasing warmth and variability that comes with spring.

April, known as “Jan-vril” by the locals, often features fast-moving cold storms that drop 30-40 cm of snow overnight. Meanwhile, the crowds disperse, especially after the Derby de la Meije. The Derby is the biggest event of the season at La Grave and distinctly marks the end of the tourist season. Nevertheless, the best powder days are sometimes yet to come.

However, great snow, base coverage, light, and reduced crowds are countered by increasing warmth, which can render large parts of the mountain unskiable in a short period of time. In recent years, the P1 station has been melted out by April, confining skiers to a tiny area (relative to La Grave) unless they are willing to undertake a treacherous hike down icy, muddy slopes in ski boots.

Once upon a time, you could come to La Grave in February and March and be virtually guaranteed a top-to-bottom descent on one of the routes down to the valley. Predicting when the snow will be good these days is much more challenging.

My advice is to keep an eye on the conditions and, if possible, plan a trip at the last minute to ensure the best skiing. Planning a ski trip anywhere is a wildcard, especially in 2024. But La Grave is even more of a gamble because so much of the skiable terrain depends upon increasingly fickle snow conditions. The wrong timing could mean your trip is limited to lapping a relatively small area near the lift.

Perhaps the best way to glean the conditions without asking a local is to inquire at the local guide's office:

Bureau des Guides & Accompagnateurs

Address: RD1091 Place du téléphérique, 05320 La Grave

Phone: (+33) (0) 4 76 79 90 21

Website: https://www.guidelagrave.com/

The La Grave website offers an “advice and conditions” page with helpful information on the current winds, temperatures, and weather, as well as the past week’s weather and avalanche conditions and the date and amount of the last snowfall.

You can also check the area’s webcams, as well as the Meteo France weather station near the top of the Télépherique for wind speed, temperature, and snow depth (the snow depth is generally off because the station is on a ridge where wind removes the snow). Although it’s farther away, a better station to check for base depth is the Meteo France Écrins station at the base of the Glacier de Bonnepierre, a few kilometers as the crow flies from the La Grave ski domain.

While La Grave is undoubtedly unique, there are other lift-access off-piste ski areas out there (although not in the abundance I would like). However, the Téléphérique is genuinely one-of-a-kind; there is only one in the world, and there will never be another.

The lift was designed in the mid-seventies by an eccentric urban transport engineer named Denis Creissels, who also had a hand in the current form of the infamous Aiguille du Midi in Chamonix. Initially opened in 1978 as a transport for tourists hoping to have a look around at the glacier, a few daring skiers began to venture here in the 80s. Today, the lift runs eight months a year for skiing, sightseeing, alpinism, mountain biking, and even paragliding.

Téléphérique is the French word for “tram,” but the La Grave Téléphérique is technically a “pulse-gondola.” Two stages service about 1800 m (5,905 ft), each comprising six groups of five gondolas holding six people each. The gondolas travel in a loop from top to bottom, passing by a station every five minutes. Thus, we can calculate the lift capacity of the Téléphérique at about 360 skiers per hour. However, the actual number is slightly lower because of transport bins and the inevitable inefficiency of failing to fit six people in each gondola.

There are four stations. The base station sits at 1,450 m (4,757 ft) in the center of the La Grave village. The next stop is P1 at 1800 m (5,900 ft). It is possible to traverse back to P1 from all of the classic descents, which makes skiing possible even when there is no snow at the bottom. The mid-station is located at 2400 m (7,874 ft); from here, the second stage of the Téléphérique makes no stops until 3200 m (10,498 ft).

Without lift lines, the Téléphérique reaches 3200 m in 35 - 45 minutes, depending on how the two stages line up. When the lift runs smoothly, it’s quite fast to get to 3200. I would estimate that 50% of the time, you can ascend in standard time.

Two factors can increase the uplift time exponentially: wind and people (the combination of both is particularly disastrous). Wind (generally above 80 km/hr or 50 mph/hr) requires the technicians to slow the lift significantly to clear the pylons. I’ve spent an hour and a half in the cabin on exceptionally stormy days (generally, the lift will close soon after if this is the case).

Because the per-hour skier capacity is in the low hundreds rather than several tens of thousands, the cabin will gather a queue with relatively few skiers. Waiting can be infuriating; luckily, it’s mostly confined to bluebird weekend powder days in February and March. Most of the time, there are not too many skiers about.

The sole additional lift at La Grave is an ancient drag lift that takes skiers up and across the Girose glacier to the Dome de la Lauze at 3,600 m (11,811 ft). The téléski has suffered immensely since its inception due to melting ice and permafrost.

SATA, the company that owns La Grave, has recently passed through plans to build a troisième tronçon (English “third stage”) up to the Dome de la Lauze, allowing a crew to tear down the old téléski. The current plan estimates that construction will finish in early 2026. The troisième tronçon will be a traditional tram cable car.

It’s worth noting that it’s straightforward to skin up this glacier; honestly, it’s hardly slower than the téléski, and a piste bully grooms a cat track across the glacier, so there are no crevasses to worry about (however, there are certainly crevasses along the descent, and you must wear a harness while skiing here).

La Grave is often described as the “most extreme ski resort in the world.” The veracity of this statement depends on your perspective. There are certainly more extreme lift-accessed areas; take the Aiguille du Midi in Chamonix, where 1000-meter 50° couloirs descend right from the top station.

Meanwhile, there are resorts where more “technical” skiing is commonplace. The first example that comes to mind is Palisades Tahoe, one of the birthplaces of extreme skiing in the U.S., where every powder day sees hundreds of local rippers sending it into the abyss off 20-meter cliffs. The phenomenon even has a name, Squallywood, referring to the fact that the most outrageous hucks are visible from the lifts.

However, La Grave is hands-down the world’s most extreme resort in terms of the easiest route down the mountain. Most skiers on the Aiguille take the classic Vallée Blanche route to the Montenvers train station, which could not be much easier from a technical perspective (although the Mer du Glace glacier’s crevasses swallow a skier or two every year). Palisades Tahoe is peppered with moderate pistes between the legendary cliffs. La Grave, on the other hand, features neither pistes nor cruiser off-piste; each run is demanding in its own right.

Longer runs are inherently more demanding, and La Grave is the king of long descents. Chancel, technically speaking the easiest route down the mountain, is 1400 m (4,593 ft) of vertical descent on off-piste terrain. Vallons to the mid-station is a mere 800 m (2,625 ft) of descent, yet it involves slopes of more than 40°; as in many parts of La Grave, a fall on the classic Mur de Vallons in hard-snow conditions could be catastrophic.

Notably, La Grave is also becoming more extreme with every passing year. That’s because glacial recession and low-snow years have transformed the ski terrain. Steeper and narrower seem to be the trends. Meanwhile, with less and less snow sticking down low, exits have become ever more desperate.

The “extreme” factor of La Grave at any given moment is impossible to measure objectively. Nevertheless, we can say with certainty that conditions play a significant role in the challenge of skiing here. A slope in powder could seem like the easiest run in the world. That same run a week later in hard snow could be lethal in the event of a fall.

Many people have died in La Grave since the Téléphérique’s inception. However, one couloir has been particularly deadly: the infamous Trifide 1. It’s hard to find concrete data on the subject. Still, the patrouilleurs (La Grave’s unique mountain guardians that most closely resemble a typical ski resort’s Ski Patrol) say over 30 people have died in this couloir in the past few decades. Trifide 1 is not the steepest or most technically difficult run on the mountain, nor the most prone to avalanches. There is no longer glacier ice in and around the couloir, and therefore no crevasses. So why has it proven this deadly?

First, Trifide 1 is among the easiest runs to access in La Grave. It’s hardly a stone’s throw from the top station. Aside from the ease of access, it’s one of La Grave’s most beautiful couloirs; the line offers 500 m (1650 ft) of continuous, fall-line couloir skiing at a delectable slope angle ranging from 45° at the very top to around 40° at the apron. That’s steep but not exceptionally so, and certainly not by La Grave standards.

While it’s heavenly in deep powder - you don’t have to speed check at all, just float down - the Trifides are hard-pack snow more often than not. The slope angle, while not overly intimidating to expert skiers, is enough to make self-arrest difficult in the event of a fall. Compounding the danger of a fall is the fact that couloir doglegs slightly in the middle, followed by a few rocks that may or may not stick through the snow, depending on the base depth. Combining this with a high volume of skiers has made Trifide 1 the deadliest line at La Grave.

It’s critical always to be aware of the conditions in La Grave. Contrary to what many skiers assume, it’s slide-for-life and not avalanches that has taken, by far, the most lives in La Grave. It’s wise never to become complacent, as a straightforward slope one day could be lethal the next.

Conditions dictate what you can ski at La Grave just as much as your level of skiing. Consider the following anecdote. In February 2023, a group of expert German skiers arrived at La Grave for a short ski vacation. Conditions at the time were terrible, as it hadn’t snowed in weeks. A layer of icy hardpack covered the mountain, and even hardcore locals were condemned to the easy classics (with many traverses back to P2, as I recall). Yes, La Grave is a mecca for big-mountain descents when conditions are right, but nobody was skiing anything at the time. These skiers asked two different patrouilleurs about the conditions in La Voûte. Both strongly advised that the group avoid that couloir. Conditions were rock solid, and a fall could be fatal. Moreover, there was an hour-long hike to exit the couloir, as that year’s snowline did not reach the valley floor.

The risk-reward ratio is an oft-used metric to judge whether an adventure is worth it. In this case, there was little reward - other than the ability to say you’d done it - and a whole lot of risk. The party went ahead and skied the couloir despite the recommendations to the contrary, and one of the skiers fell; due to the hard snow, self-arrest was impossible, and the skier sustained fatal blunt trauma to the head pinballing down the rocky chute.

As technical as the skiing can be in La Grave, the route finding is even more difficult. There are simply so many routes and variations within routes; even long-time locals are not always 100% sure of a route (of course, they come prepared to backtrack or rappel if needed). The glacial recession has completely changed the character of many routes over the past three decades. Avalanches, changes in forest growth, rockfall, and other natural cycles can also alter routes from year to year.

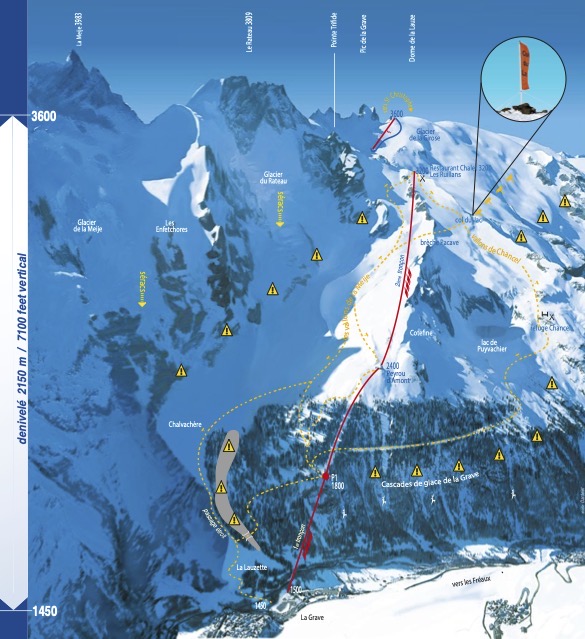

Adding to the pressure, knowing where you’re going in La Grave is crucial because many hazards are not marked. The resort itself provides an elementary map that offers a basic outline of the mountain’s layout and the location of the main itineraries, but not much in the way of detail:

I’ll discuss the general layout of the mountain’s main routes, known as the “classics,” and then talk about a few other areas and itineraries in the general region. There’s a lifetime of discovery in La Grave, and no written guide will ever serve as a substitute for experience. It’s one of the reasons so many folks choose to hire guides here.

Still, on any given day in La Grave, the majority of people are skiing without a guide; whether you hire a guide or ski on your own, understanding the mountain is integral to the experience here.

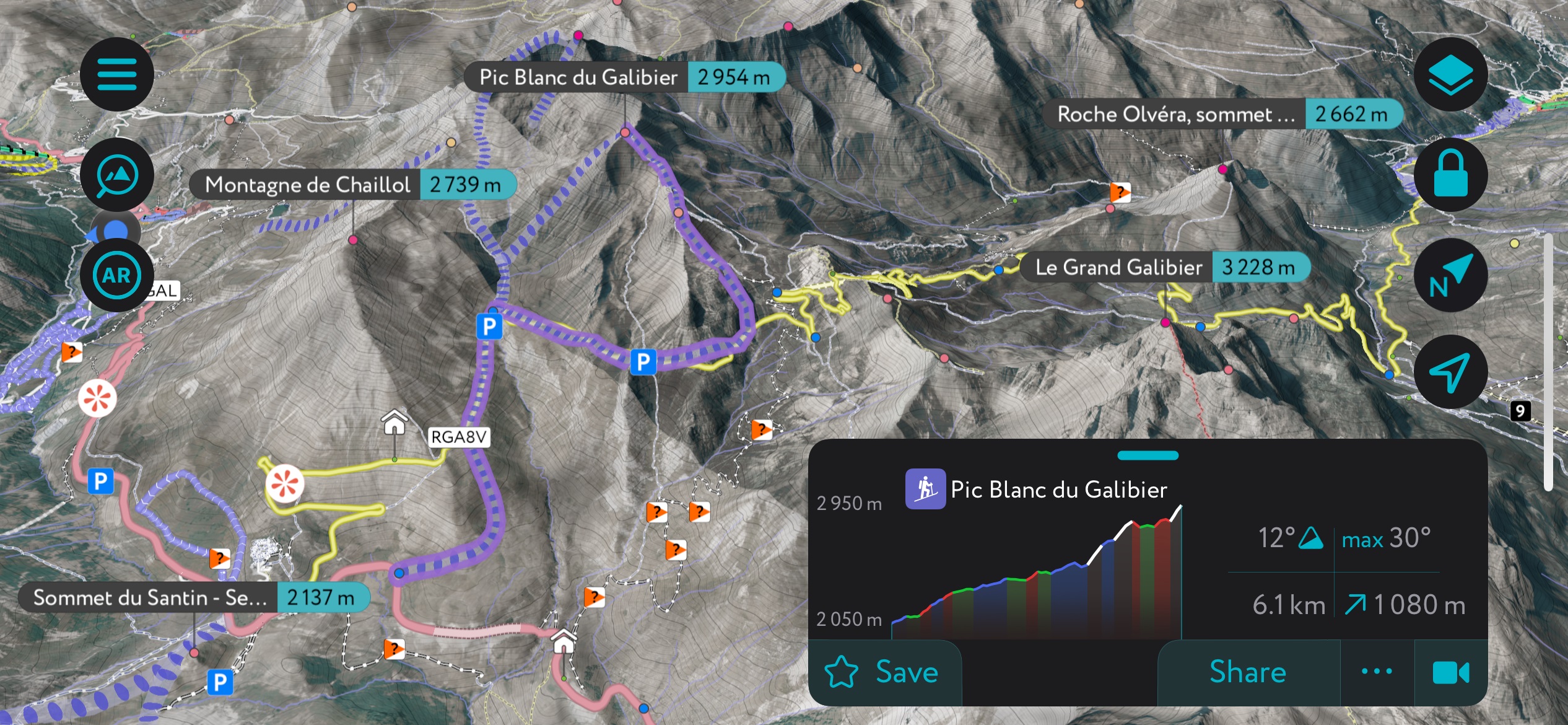

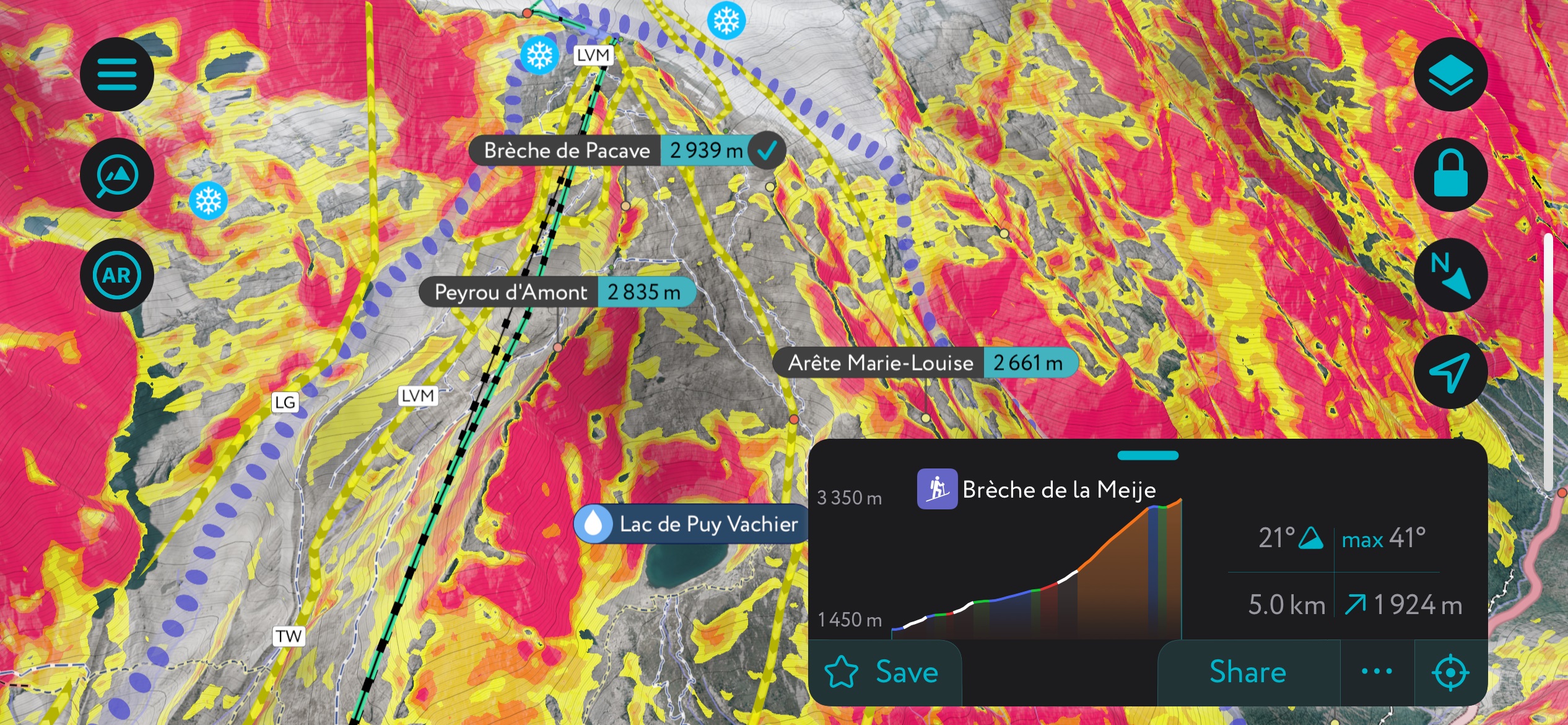

The PeakVisor App is a handy tool for big mountain environments like La Grave. The app features several tools that make navigation on the classic routes more straightforward and open up new opportunities around the resort. Plus, there are thousands of backcountry ski tours throughout Europe, including the nearby Col du Lautaret. I also uploaded a few of the classic routes in La Grave.

La Grave straddles the middle of the massive north face of the Écrins massif. Many glacially carved bowls and valleys make their way down to the narrow Romanche Valley floor; nearly all these are skiable. Incredibly, the Téléphérique was not designed as an access to the most extensive north-facing ski terrain in the world. It was all luck that it happened to be so.

The two main passages heading to the valley floor are the Vallons de la Meije (known simply as the “Vallons”) and the Vallons de Chancel (known as just Chancel). The Téléphérique crawls up the mountainside roughly following the ridge that divides these two descents.

The Téléphérique begins in La Grave village and ends at 3196 m (officially named Ruillans, but often simply referred to as 3200 or “trois mille deux” in French) on a ridge just above the Girose glacier. Vallons is the skiers’ right, on the side where the lift travels (you can scope out some of Vallons from the lift). The skiers’ left is Chancel. The north-facing wall of the Écrins massif continues east-to-west, divided by ridges. Between these ridges are the various itineraries that descend to the Romanche Valley, including Freaux, La Voûte, Chirouze, Enfetchores, and more…in all, there are well over a dozen itineraries to the valley floor.

Going up higher from the station at 3200 m, you have the drag lift up the Girose glacier. A few classic descents down the Girose terminate with a traverse across the Col du Lac, back into the Chancel zone for a classic finish. The Girose also serves as the starting point for the Chirouze and Voûte itineraries.

South-facing descents from the top of the drag lift descend to the town of St. Christoph, perched at 1800 m (5,905 ft) in the heart of the Écrins National Park. It’s an entirely different valley; it takes 45 minutes to drive back to La Grave.

Throwing skins on opens up a range of ski touring opportunities. Some tours along the upper reaches of the Girose glacier are straightforward. However, tours leaving the Girose to venture deeper into the Écrins are significantly more complex and hazardous. Nevertheless, several mountain refuges offer unmatched opportunities to base at 3000+ m in the Écrins National Park.

The Vallons is the most classic of all the classic variations. Skiers get a clear view of the Vallons from the Téléphérique as they ascend. It’s effectively a large, wide gully - hence the ‘valley’ connotation - that descends to the forest and eventually the valley floor.

The Vallons is the product of the once formidable Glacier du Vallons and its runoff. The gully is enclosed on the skiers’ right by the ancient moraine of the historical terminus of the Glaciers de la Meije; the other side of this moraine is known as the “Zone Interdit” due to the frequent snow and ice avalanches that come down from the various glaciers and faces of La Meije.

You can ski the Vallons to any of the three stations, depending on the conditions. Sometimes, it’s appropriate to peel out and traverse to the 2400 m mid-station. Skiers often follow the Vallons traverse back to the P1 station at 1800 m. Or, you can navigate the track all the way to the Romanche River, with a short 50 m (165 ft) hike back up to the parking lot of the Téléphérique (slightly more complicated than the other two options).

With the exception of the traverses back to P1, the Vallons is really the only La Grave route that will regularly develop moguls from skier traffic. It’s the easiest route on the mountain from a route-finding perspective (and one of the easiest from a skiing perspective, although Classic Chancel is probably easier). Still, it is often flat, chalky, and buffed out from the wind. On these days, it can be the best descent on the mountain.

The second half of the La Grave classic descents is the Chancel, a large bowl on the skiers’ left of the ridge that divides the ski area. The Chancel offers a range of terrain options from La Grave’s mellowest slopes to steep couloirs.

The skiers’ left side of Chancel, considered the classic, consists of a series of small bowls and gullies. Many options exist, and it would be possible to ski this zone for days without taking the same line twice. These are stress-free runs, with comparatively mellow slope angles and less avalanche danger than other areas. The Chancel classic is a go-to on high avalanche danger days. Here, you can enjoy large tracts of powder and suss out the conditions simultaneously.

At the finish of every Chancel route, you must traverse back to P1. The traverse is evident with many tracks and moguls. It’s impossible to lose your way. Furthermore, a rope (one of the few in La Grave) delineates the traverse's lowest point. If you reach this rope, start going right. Below is an unskiable cliff band.

Staying skiers’ right on Chancel, against the ridge that divides Chancel and Vallons, is another excellent option. The slope eventually opens up into a large bowl called the Combe de Pacave. The Combe offers one of the most wide-open slopes in La Grave, and it tends to fill up with powder during storms that approach from the West (which is the vast majority). The catch is that, once you’ve descended, it’s mandatory to ski either of two couloirs: the Banane or the Patou. While these are the most introductory couloirs in La Grave, they are still serious lines that can present slide-for-life hazards in hard snow and avalanche danger in deep snow.

A third couloir de lac is the eponymous “Couloir de Lac,” best accessed from the skiers’ left Chancel classic.

Alternatively, you can stick to the right for the top of Chancel but cross over the ridge to the Vallons at the Brèche de Pacave just above the Combe. Skiers often use the Brèche to catch the Vallons traverse back to the mid-station if the bottom of the mountain is in poor condition.

The Girose is a staple of the La Grave experience. The comparatively mellow, wide-open slopes are a haven for powder skiing. March and April especially can boast incredible conditions on the glacier. The lightest snow I’ve ever seen was on the Girose in April.

Crevasse fall is a hazard; people break through snow bridges, especially during thin years. It’s essential to wear a harness on the glacier so the patrouilleurs can winch you out in the event of a crevasse fall; see more on crevasse rescue here. The skier in the above video skied irresponsibly close to a visible undulation in the glacier. I don’t believe that a fear of crevasses should deter skiers from enjoying the Girose. Moreover, because the Girose is a relatively small glacier, the risks posed are not as severe as in Chamonix, for example.

The “téléski” drag lift, once servicing both the Pan de Rideau entrance and the Dome de la Lauze, has become a shadow of its former self due to the glacier’s recession. It now requires a tow-behind by a groomer, and as of February 2024, the drag lift is only servicing about 60% of the way up the Dome. This makes it somewhat more challenging to ski the glacier now than before. Nevertheless, every corner of the glacier is accessible by skinning, and technological advances have made crossover alpine touring bindings commonplace and reliable.

One important thing to keep in mind on the Girose is that you must exit the glacier at Col du Lac. The Col is denoted by a giant flag and many traverse tracks heading to the skiers’ right. Continue onwards, and you’ll come to a rope warning you about the dangerous terrain ahead. A failure to turn back at this point means you’re committed to skiing La Voûte or any other number of complex route variations to the valley, all of which require a rappel.

The Trifides are flagships of La Grave couloir skiing. The couloirs take their name from the Pointe Trifide (3,450 m / 11,319 ft); they bisect a satellite buttress between the Glacier du Vallon and the Zone Interdit. Several variations include Trifide .5, 1, and 2, with 1 being the most popular.

The Trifides are incredibly easy to access from the Vallons side of the ski area. They are high and thus receive ample snow even in low-snow years. Nonetheless, as discussed earlier, these couloirs are also the deadliest in La Grave. The Trifides occupy a unique niche in La Grave; they are as committing as some of the more extreme lines but with none of the access and route-finding barriers to entry.

In recent years, the diminishing ice on the Vallon glacier and the couloir itself has made Trifide 1 harder to enter. More often than not, the top entrance now requires a rappel. Meanwhile, the side entrance, more accessible in good conditions, is often scratched out with rocks protruding and can be quite tricky to navigate. Trifide 2 and .5 both require a move to get in and although I often find this move easier than a skied-out Trifide 1, these couloirs are more technical and committing.

The Zone Interdit refers to the terrain under the Glacier du Rateau and the Glacier de la Meije. It translates to “forbidden zone” in French because of the exposure to the snow and ice that frequently come down from La Meije. The terrain is not overly technical. In fact, it’s easier than the Vallons. However, avalanche debris and occasionally ice blocks from fallen seracs can make things more challenging.

“Forbidden” is a bit of a misnomer; the zone is relatively safe, and guides often take their clients here. However, many tourists will stop and hang out, which is not the best idea. While it’s improbable that a serac will break off just as you pass under its path, it’s important to understand how the mountain works before you get comfortable in the Zone.

Following the Zone Interdit, the main valley descent into La Grave village is a classic for locals and a great beginner itinerary for tourists. Skiers trend right along the Zone Interdit. Where you start to see stunted Larch trees growing, you can stay left to join the traverse to P1 or traverse right to the raised ridge of an old moraine. Dropping into the valley, skiers have an epic descent beneath the Glacier de la Meije.

Various tricks will get you into this zone in different places; a side-step will get you in with a long descent along mellow gullies. Meanwhile, you can stay low to ski a steep face into the bottom of the valley to the base of the forest. This bowl can sometimes fill with massive amounts of ice and avy debris, making skiing all but impossible. When that happens, it’s necessary to drop in low.

The traverse takes you through a small larch forest and back to an alpine meadow called Chalvachère. A cabin sits to the skier’s left. From here, the descent follows the right side of the deep canyon de la Meije. Eventually, you join a trail, then a road onto the Lauzet, where a last pitch of open fall line brings skiers to the river. A short 50 m (165 ft) stair climb (the “stairs of doom,” as they have been affectionately dubbed) is required to return to the Téléphérique parking lot.

Route finding here could be tricky, save for the hundreds of tracks demarcating the route. If you somehow tag this one first, just be sure to stay to the right of the deep canyon!

Because there are no pistes in La Grave, the descents are known as itinéraires, which directly translates to “routes” in English. All descents in La Grave are routes, so to speak, rather than trails. The itinéraires designation generally refers to the big descents that reach the valley bottom and require specialized skills, i.e., glacier travel, rappelling, and route-finding.

The guts of these lines usually have enough snow, even in dry seasons; however, the exits have been getting increasingly dicey over the past years. You can forget about “good” snow conditions at the bottom; just hope you can keep your skis on.

You can check out Pelle Lang’s encyclopedia of La Grave itineraries for a bit more beta.

The Fréaux couloir is one of La Grave’s finest and makes for an excellent first itinerary. Because it starts in the forest at the start of the Chancel traverse, it requires less route-finding and stamina. The couloir itself is a 40-45° hallway with high walls and an aesthetic ambiance.

Nevertheless, this is a serious couloir. Snow conditions are not as good at this altitude, and the couloir is often filled with rocks and holes with rushing water beneath (it’s a river in the summer). Getting down beneath the couloir, it’s a bit of hide-and-seek with sections of wills and viscous shrubs interspersed with skiable meadows.

La Voûte stands as the classic La Grave itinerary. Once a well-guarded secret, locals went out of their way to hide this line from hungry guides hoping to take clients down. Eventually, tracks tell all and the line became a classic.

Skier traffic isn’t the only thing that’s changed about La Voûte in recent decades. In French, La Voûte means “the arch.” The couloir was dubbed as such because the tongue of the Girose glacier reached the rappel station about halfway down, forming a giant arch of ice. Apparently, these seracs held on until as late as the early 2010s. Seeing the glacier’s terminus now - kilometers up the mountain - makes it hard to imagine that the Girose will exist at all in a few more decades.

Looking on the bright side, the Girose glacier’s recession means less overhead hazard for skiers in the lower section of this magnificent network of couloirs. Between the endless glacier start, the thousands of meters of sustained 40°, north-facing couloir skiing, and even a bit of tasty tree skiing toward the bottom, the known universe doesn’t get much better than this for lift-access skiing.

Of course, you must always pay your taxes at the end of a fruitful year. Be prepared for a fight to exit through the rocks, willows, and brambles that guard the last few hundred meters to the road.

There are two main descents to St. Christophe. The Col de la Lauze, usually just called the ‘classic,’ drops to the left of the top of the drag lift. It offers a massive descent on wide-open slopes.

Couloir La Rama drops a bit further afield, and crossing over the top of the resort to Les 2 Alpes is necessary to access it. There are a number of large bowls leading to various couloirs, and you’re likely to get cliffed out in a bad way if you don’t know where you’re going. One common mistake is thinking that the route follows the Ruisseau de la Rama; it actually follows the Ruisseau de la Chioura, the next large drainage bowl. You can line yourself up with the green tower at Les 2 Alpes for reference.

The advantage of traversing above is making much less of a traverse down below in the Vallée de la Selle and getting more vertical drop. La Rama is one of the best couloirs I’ve ever skied, and, as a south-facing line, it’s easy to get in spring condition. It’s unbelievable bowl skiing up top leading to an elevator shaft couloir down to the narrow valley. The traverse back to Saint Christophe doesn’t feel as long from here.

The only problem with the St. Christophe descents is arranging transportation back to La Grave. Whether you shuttle a car to the bottom or hire a taxi, it’s a lot of time and money, which is why I don’t ski these lines more often.

Chirouze is the next north-facing drainage over from La Voûte. It’s a La Grave mega-classic; the only thing between Chirouze and Heaven are the exits, the worst of any of the itineraries I’ve included here.

Chirouze offers a complete glacier start with a big descent down the Girose, trending left instead of right, as you would for La Voûte. It’s not one specific line but a series of bowls and couloirs, with endless variations possible. It’s generally divided into Chirouze droit, gauche, and centre; skiers’ right, left, and center.

The skiing isn’t overly technical, and the bowls as you drop in are sublime. It’s one of those magical zones where the powder is light, dry, and not wind-affected like other parts of the mountain. Nevertheless, you’ll need your skills and energy for the bottom, which usually involves lots of rappelling, picking around rocks and trees, and hiking. Keep a pulley on your harness for the Tyrolean across the river at the bottom or trend right to exit as for La Voûte.

The Pan has long been the ultimate La Grave run. It’s a harrowing traverse followed by a genuinely steep (50+°) face and a glacier descent that can only be described as mind-blowing. It’s the kind of run where experienced skiers can have what is definitively the best run of their lives.

Like many other runs on this list, the Pan used to get skied far more often than it does now. As I’ve mentioned, low-elevation snow coverage and glacial recession are the main culprits for the increased challenge of skiing at La Grave, and in this case, it’s the latter. The drop in the Rateau Glacier has caused the exit couloir on the Pan face to become much longer and steeper. What used to be a relatively short 50° face is now a 50° face plus a ~53-54° exit that is always icy (I just watched this video from 2011 to confirm the difference). A sometimes-open bergschrund poses a final challenge before you’re off the face and onto the fat, more straightforward glacier.

Moreover, the glacial recession has ended the drag lift that once brought skiers to the entrance; it now requires a 200 m (660 ft) skin, which in turn requires touring gear, effort, etc.

The advantage of the added difficulty is that the Pan gets skied less now. The disadvantage is that it’s a more dangerous, less fluid descent than it once was. Fortunately, you can still ski back to P1 at the end.

The Enfetchores is by far the most popular multi-day mountaineering mission from the Téléphérique (it can also be done in a single day). It’s an impressive 2000 m (6600 ft) descent back to the village of La Grave or even back to P1 if the valley is melted out in the spring.

The long approach means this line doesn’t give you a lot of bang for your buck in terms of skiing. The standard route is to go off La Meije's backside, stay in the Promotoire refuge, and climb the Bréche de la Meije the next day. A fit party could do this in a long day. Another option for a single-day approach would be the Ginel, a steep boot pack up the glacier, but this route is highway exposed to objective risk from overhanging seracs.

Once above the Enfetchores, it’s a 1000 m (3300 ft) of fall line, wide-open skiing until you reach a series of rocks and cliffs that must be navigated into the Zone Interdit of the main ski domain. Finish on the classic descent to the valley or the traverse back to P1.

How to begin? You may be thinking, “This article is already very long.” Well, it would take a 26-volume encyclopedia to fill up all the ski touring opportunities around La Grave. Here are a couple of the most classic zones that best showcase the region.

The Col du Lautaret (2,058 m / 6,751 ft) is a mountain pass on the north side of the Parc Nationale des Ecrins on the French 1091 highway. The pass offers easy access to a considerable diversity of ski touring. The top of the pass is about 20 minutes from La Grave.

“The easy road access to such varied all aspects, and all level terrain is more than rare. The fact that the touring season stretches from early November to mid-May most years is exceptional”, says Per As, La Grave mountain guide, on why the Col du Lautaret is his favorite place to ski tour.

Tours are accessible from the top of the Col du Lautaret and from many points to the east and west. The small village of Le Casset is an excellent staging point, and Arsine offers a lifetime of lines and a refuge.

Much of the skiing is not visible from the road. Driving over the col, it may seem like everything is tracked out. The truth is that there are plenty of lines remaining out of sight. Nevertheless, the Col is no secret, and the easy access routes can be littered with people. It’s undoubtedly the most crowded backcountry skiing domain in the region.

The Aigle, which means eagle in French, is worlds apart from the Col de Lautaret. Whereas the Col offers access, the Aigle takes thousands of meters of climbing to reach, no matter if you leave from Villar d’Arêne or the top of the Téléphérique. It’s a technical approach with a lot of time spent crossing glaciers, namely the Tabuchet.

The aptly named Aigle sits perched above the ice on a rock spire at ~3500 m (11,500 ft). Incredibly, this refuge was first constructed in 1910, renovated several times, and rebuilt in 2014. Getting to the refuge is itself an accomplishment of alpinism, and as a result, this refuge mainly attracts alpinists going for La Meije and other technical objectives. Nevertheless, the descent down the Tabuchet is one of the world’s most epic, especially if there is snow to the valley.

La Grave lift passes are expensive for what they are, considering there’s one lift and few on-mountain amenities. Still, at €59, it’s cheap compared to many other ski destinations.

A season pass runs about €1,050, and the “supernova” pass, which accesses La Grave, Alp d’Huez, Deux Alps, and several other nearby resorts, is only €1100 - the best value if you’re looking for more than a few weeks of skiing.

Single-ride tickets are available for those looking to do a mountaineering route or refuge stay without skiing much at the resort. There are also discounts for weekday-only passes, students with ID, persons under 25, and multi-day admittance for up to 10 days. Check out the website for more info.

La Grave isn’t exactly a bastion for cross-country skiing, as there isn’t much flat space around. Pied du Col is the spot to go if you do happen to get the craving. Snowshoeing is popular; many local refuges serve as many snowshoers as backcountry skiers. Snowshoe routes tend to follow the valley, whereas the skiers branch off toward the peaks.

Pied du Col is your typical cross-country ski center. It’s not exceptional by any means, but there is a nice loop around the Romanche River. The track is groomed regularly. It’s at the base of the Écrins massif and is also a gateway to the Écrins National Park, and the scenery is stunning after a fresh snowfall.

La Grave, microscopic as it is, knows the value of a good tourist office.

Office de Tourisme des Hautes Vallées: Bureau de La Grave

Address: RD 1091, 05320 La Grave

Phone: (+33) (0) 4 76 79 90 05

Hours: Monday through Saturday, 9 a.m. to 12 p.m., 1:30 p.m. to 5 p.m., Closed Sunday

Website: https://www.lagrave-lameije.com/fr/hiver/accueil

For guiding services or technical questions about the resort, contact the Bureau des Guides in La Grave.

Bureau des Guides & Accompagnateurs

Address: RD1091 Place du téléphérique, 05320 La Grave

Phone: (+33) (0) 4 76 79 90 21

Website: https://www.guidelagrave.com/

Other guiding services include the legendary Skier’s Lodge:

Skier’s Lodge

Address: Hotel Des Alpes RD 1091, 05320 La Grave

Phone: +33 (0)4 76 11 03 18

Website: https://skierslodgeguideservice.com/

Email: info@skierslodge.com

And Snowlegend:

Snowlegend

Address: RD 1091, 05320 La Grave

Phone: +33 (0)6 81 97 03 25

Website: https://www.snowlegend.com/?lang=en

No French ski vacation is complete without Montagnard cuisine, and La Grave delivers in this department. Not all the restaurants are excellent; I’ll give my recommendations for the best options. There’s a bakery, a small grocery, and a cheese and cured meat shop. There’s also access to all sorts of regional products in Briançon at their market on Sunday mornings. The La Grave market is on Thursdays in the Salle des Fêtes but is limited compared with the Briançon one.

The food on-mountain at La Grave is stellar, and I don’t give out easy compliments when it comes to food. Both La Cabine 3200 at the top and the Refuge Evariste Chancel are tasty, fast, and affordable, all essential criteria. I eat here more than anywhere else in La Grave.

La Cabine is the central hub of the resort. The views are magnificent, and nothing beats the deck overlooking the Girose on a sunny day. My go-to's are the pizzas and the rotating Plat du Jour (get there early because it’s apt to sell out).

Refuge Evariste Chancel is even tastier than the top restaurant. It’s got a homemade feel and a rustic atmosphere overlooking les Couloirs des Lac. They do omelets, tartiflette, and a rotating plat du jour, among other dishes; you can’t go wrong.

Le Vieux Guide (The Old Guide) is the restaurant I eat at in La Grave more than any other. The place is adorable, tucked into a little basement below the main street of La Grave. Heads up: the descent down the alleyway to the restaurant can be gnarlier than any run on the mountain.

Once you’ve gained the entryway, possibly with crampons, an ice axe, and a rack of ice screws, the appreciation starts with the atmosphere. It’s a cozy, romantic setting with a close-knit, communal feel. If you spend much time at refuges in France, you’ll recognize this vibe.

Next, we have the food. It’s on the fancy side of Montagnard, so there are escargots in addition to fondue. They have several prix-fixé options for three or four-course meals. I know next to nothing about wine, but it always seems to taste good here. The owner, Seb, has been in the game for a long time, and everything is supremely organized.

When it comes time to pay the bill, I always find the price reasonable. I can’t ask for more.

Le Faranchin is Villar’s answer to Le Vieux Guide. Villar is five minutes up the road from La Grave.

Like Vieux Guide, they are organized and offer excellent cuisine at a reasonable price point. The menu, however, trends a little more toward regional Montagnard specialties like agneaux (lamb) and tête de veau (calf’s head).

If that’s a little adventurous for you, the steak tartare and fondue are among the best. Still too bold? They also have a burger.

The atmosphere is swanky, and while it’s not as cozy as Le Vieux Guide, it’s perhaps more comfortable for a French-style two-hour dinner.

Although the après-ski scene in La Grave doesn’t feature the massive parties and disco music traditionally associated with famous European ski resorts, visitors should not dismiss the opportunity to celebrate the day with a beverage and meet other skiers from around the world. Not only is there no place I’d rather ski, but no place I’d rather have a beer after skiing.

The Castilian is the life and blood of the La Grave après scene. Starting in February, the sun begins to shine in town in the afternoons, and skiers gather for the daily debrief of their exploits. Nothing beats melting into your chair in the sunshine after a long day on the mountain with a beer and a basket of fries from the small outpost that serves food on the terrace.

The chance to sip beer and wine (rather than chug it), meet new people, and hear what others are saying is a revolution in the annals of après-ski history.

The K2 Pub is nearly as indispensable to La Grave history as the Téléphérique itself. The pub forms the lively bottom floor of the Skiers Lodge, the legendary La Grave guiding center and hotel. It’s quiet and cozy, and the dim lighting accentuates the decades of La Grave ski paraphernalia adorning the old walls. It’s a solid place for après in January before the sun rises over La Meije, but as the season progresses, Castillion takes the cake.

Of course, the pub is the spot if you’ve overstayed the Castilian terrace and need somewhere to continue the party, albeit with a little more warmth. They also have a kitchen with tapas and other menu items, and it’s cheaper than the Castilian.

Whereas La Meije is the queen of the day, the K2 is the queen of the night. Friday nights feature music and a general rootsy skier vibe that is, in my humble opinion, unmatched in any other ski town. In the heart of the season, you can find some kind of party here every night of the week.

The Derby is the culmination of the season; it’s like the closing day party at other resorts (La Grave’s closing day is often a bit sad because everybody has already left town).

The Derby itself is a race from the top of the Glacier to Chalvachère. Hundreds of competitors put their lives on the line in pursuit of the glory of a top finish. The true prize is the music and partying in town, however, and the hundreds of funky people that make their way into La Grave for the annual pilgrimage.

The town's beating heart becomes the Chapiteau, the French word for a circus tent, where bands perform, and an inconceivable amount of tobacco smoke is released into the atmosphere. Heads up, though; somebody made off with my jacket last year.

Playing music outside the Original La Grave shop is the après scene closest to my heart. Once the sun pops over the Meije in March, Bruno clears off the deck and sets up for musicians to come by and play music with each other. Everybody is welcome to play; the best shows feature dozens of musicians from La Grave and abroad taking turns jamming and playing songs. The community doesn’t get better than this.

You can buy beer at the Castillan and bring it over or bring your own (to save a bit of money).

La Grave doesn’t shine in the lodging department; rooms here are simply a means to an end for resting up before the mountain. Don’t expect a lot of luxury. The bright side is that accommodation here is affordable. You can score a room for less than €30 a night in 2024.

If you have a group, Airbnb may be your best bet. Each village has dozens of listings, and the going rate is €50 - 100.

Gîtes are like the French version of hostels. You can find a cheap room and a hot meal. Camp de Base in Freaux, Gîte le Rocher in La Grave (right next to the Téléphérique), and the Auberge in Villar are all examples.

Hotels include the Castillon, Edelweiss, and Hotel des Alpes in La Grave, and Les Agneaux and Faranchin in Villar d’Arêne.

It’s difficult to recommend a place since I’ve never stayed in a hotel here. Google reviews will be much more reliable.

Mountain huts are a perfect way to experience not only La Grave but the entire Alps. Fortunately, the area has several great huts with excellent atmosphere and access to skiing.

Evarist Chancel Mountain Hut: One of the best opportunities while visiting La Grave is a stay right on the mountain. Theoretically, you could stay here and be the first on the second stage of the Téléphérique on a powder day.

Open from 16/12/2023 to 22/04/2024, daily.

Mountain Hut Pic du Mas de la Grave - Chez Polyte: A recently renovated hut that offers easy access for those not willing to climb.

Open from 20/01 to 23/03/2024, daily.

Goleon Mountain Hut: A beautiful, recently renovated hut with access to some of the best backcountry terrain in the Alps.

Open from 03/02 to 01/04/2024, daily.

Le Chazelet is the adorable, family-friendly ski resort just up the valley in Chazelet village (still technically the Communes de La Grave).

Serre Chevalier Ski Area offers wide pistes, freeriding itineraries, hike-to terrain, and a lift system stretching over several peaks.

The resort comprises several base villages, including Briançon, Chantemerle, Villeneuve-la-Salle, and Le Monêtier-les-Bains. It is the largest ski resort in Provence-Alpes-Côte D'Azur, with more than 250 km (155 mi) of slopes and more than 60 ski lifts, which reach 2,800 m (9,186 ft). The tree skiing amongst ancient larch forests is enchanted. It’s some of the best in Europe when there is snow.

Speaking of snow, there’s usually plenty of it. Serre Chevalier gets storms from multiple directions. They also have extensive snowmaking on the pistes. Another aspect of Serre Che is the access from Briançon, which is unique among European ski towns. The historical Old Town dates back 400 years. The restaurants and accommodation are affordable. There’s none of the glitz and glam of other ski resorts — all of that exists in the other base villages. Briançon is a bit rough around the edges in a way that I appreciate.

Alpe d'Huez is a French megaresort sprawled across the southern flank of the Grand Rousse Massif. You can see the top station clearly from La Grave, even though it takes 45 minutes to drive here.

Alpe d’Huez is enormous; over 250 kilometers of slopes offer something for skiers and snowboarders of all levels, from beginner runs to extreme off-piste terrain where one mistake could send you tumbling to your death. The summit reaches 3,330 meters, and the elevation and favorable geographic location guarantee snow cover throughout winter.

One of the best features of Alpe d'Huez is its extensive lift system, which efficiently transports skiers across the sprawling ski area. The resort's iconic "Sarenne" run, one of the longest black runs in the world, snakes 16 kilometers from the Pic Blanc summit to the valley.

An impressive amount of off-piste is scattered throughout the area, although it takes a day or two to locate the best spots. I recommend the freeride zone to the lookers’ left of the large tram on the Vaujany side of the mountain.

Alpe d’Huez features a variety of aspects, but the dominant aspect is south. They get an impressive amount of sunshine, which can be great for the mood but not for snow quality. I’ve often felt Alpe d’Huez is icy compared to other resorts in the region, especially in the mid-winter. On the other hand, the spring skiing here is top. The slopes soften up by mid-morning with the sun, and it’s an all-you-can ski slush buffet.

It’s a megaresort (purpose-built as a ski resort in the 70s), but there are still a number of great eats in town. My go-to for a quick meal is Captain Sandwich. It’s cheap, tasty, and easy to ski to.

Les Deux Alpes, located on the west aspect of the Meije Massif, is a massive and renowned megaresort, attracting millions of visitors every year. Les 2 Alpes offers a vast ski area spanning altitudes from 1,300 to 3,600 meters, with the top connectable to La Grave by a short hike. The glacier, one of the largest skiable glaciers in Europe, ensures excellent snow conditions throughout the year. These guys have one of Europe's longest summer ski seasons, although that is sadly changing.

Beyond its extensive ski terrain, Les Deux Alpes boasts an uproarious après-ski scene (full of Brits) and a variety of off-slope activities. Unlike La Grave, the resort offers plenty of luxury wellness facilities, such as spas and thermal baths.

Les 2 Alpes is too crowded and hectic for my taste. Any given week will bring more skier visits than an entire season at La Grave. However, summers here are incredible, with the ski lifts remaining operational to serve a network of finely sculpted bike trails.

Briançon, the highest city in France, sits at an altitude of 1,326 meters at the convergence of five valleys. This city is a destination for mountain enthusiasts and tourists visiting the Old Town. With incredible access to climbing and skiing, many high mountain guides are based here.

The original settlement was fortified by French military architect Vauban in the 18th century. This central Old Town is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its remarkable fortifications built between the 18th and 20th centuries. A tour will take you through the Vauban citadel, the fortified castle, and the surrounding forts, including Salettes, Trois Têtes, and Randouillet.

Architecture enthusiasts can explore the 18th-century collegiate church of Notre Dame, the 14th-century Cordeliers church, old houses lining the steep, narrow streets, and the charming Place d'Armes square surrounded by pretty, colorful Provence-style facades, fountains, and sundials.

Briançon has since sprawled over a wide swath of the surrounding valleys. The base villages of the Serre Chevalier Ski Resort extend to the northwest, while Montgenèvre branches off to the northeast. The newer construction is not sightly compared to the Old Town, but Briançon still has charm. Even with access to excellent skiing, climbing, and history, Briançon has remained (relatively) affordable.

If you visit La Grave, you will likely pass through Grenoble. While not the most beautiful French city, Grenoble has a certain charm, and it’s worth spending a day here to experience the vibe. After all, it’s not called the Capital des Alpes for nothing. The city is surrounded by the Vercors, Chartreuse, and Belledonne Massifs and is proximate to the Écrins.

In addition to the obvious mountain sports culture, the city has an intellectual atmosphere due to its status as an academic research hub. There are also plenty of artists, musicians, and bohemians. Grenoble has a great music scene for a medium-sized city. Restaurants of every sort - not just French cuisine - are clustered throughout the downtown.

With every necessity readily available and plenty of affordable hotels, Grenoble is an excellent place to stage a visit to La Grave. The LER 55, bound for La Grave, leaves the Gare de Grenoble twice daily. BlaBlaCar, a ridesharing service, is also an excellent travel resource in France.