Your Go-to Guide on the Best Resorts, Backcountry, Cultural Experiences, and More!

Skiing in Japan means entering an otherworldly domain of bottomless cold snow, sushi, onsens, and very little English. The ancient culture, smiling faces of locals, and juxtaposition of city and countryside will define your trip as much as the skiing. Japan offers the world’s most exotic and cultured destination for lift-access skiing; however, there’s information and planning to sift through before you head over. In this guide, I’ll compile all sorts of JaPOW skiing wisdom to make your trip that much more special.

Heading to Japan

Japan, an island nation, is far from a lot of places. Yet, Tokyo is the largest city on Earth (pop. 29 million), so it’s easy to fly to.

Flights

Flights to Japan are remarkably affordable. For example, a flight from New York City to Tokyo, a massive journey, goes for less than USD 1500 during peak ski season - with ski gear. It’s possible to fly from California for less than USD 900. Meanwhile, flights from Europe are around €800.

Two major airports access the ski areas: Tokyo on the ‘main island’ of Honshu and Sapporo on the northern island of Hokkaido. Once there, you can also connect to smaller airports like Akita, about halfway between Tokyo and Sapporo (several hundred kilometers driving from Tokyo).

Travel Expenses

Japan is one of the world’s most technologically advanced and developed countries, with the highest life expectancy worldwide. Thus, people are often surprised at how affordable the country is, especially when it comes to skiing. Check out this list of typical travel expenses for a ballpark of prices.

Moreover, the yen is weak against the U.S. Dollar and the Euro (Dec. 2023) because Japan hasn’t raised interest rates like other countries in the past few years. The current exchange rate of 150 yen per USD means that Japan is about 25% cheaper than a few years ago, although imported items have inflated to match the weaker exchange rate.

Some things are expensive. If you’re on a budget, you’ll want to pass on spending too much time in Tokyo, as the prices there are much higher (though not outrageous). In recent years, the lodging at Niseko and the most popular resorts has become much more expensive.

On the other hand, renting a car, transportation, lift passes, gear rentals, food, and drinks are all reasonably priced (again, stay away from Niseko). Lift tickets usually cost about USD 40-50, while a good ryokan (traditional guesthouse) would be in the ballpark of USD 100; not bad, considering it includes breakfast, dinner, and, frequently, an onsen.

Translation

Translation used to be a far bigger issue than it is now. The rise of smartphones has made it possible to communicate with just about everyone. For those unfamiliar, you can download an application like Google Translate and have any text translated onto your phone. You can also have the app vocalize Japanese translations for any text input.

Hardly anyone speaks English or any other Western languages, so you’ll be using translators frequently - make sure your phone is charged!

Try to learn a little Japanese before your trip. The locals will adore you for it. It’s not that hard, surprisingly. Don’t worry about the writing (this is very difficult); just practice speaking some basic phrases.

Japan was an insular country for centuries - no foreigners entered the country for two hundred or so years during the 18th and 19th centuries. There are still insular elements within their society, i.e., it’s difficult for foreigners to move there. To put in just a few hours of your time to learn their language is the least we can do for this hardworking and hospitable society that has recently opened its doors to the world.

Transportation Around the Islands

Japan has an incredible rail network. The high-speed bullet trains efficiently traverse the country in all directions and feature little sleeping cabins for overnight journeys.

As skiers, readers will likely be more aware of their carbon footprint, and one thing you’ll notice about Japan is how economical everything is. Public transportation is excellent. Lodging is small, especially in Tokyo. Cars are smaller, similar to Europe. Portions are moderate.

As much as I’d love to recommend using public transportation, a car is integral for many skiers looking to get out and about and experience some of the less well-trodden areas of Japan.

Renting a Car vs. Trains

Trains in Japan are incredible. You could use just public transportation for a trip to Shiga Kogen or Niseko, as well as several other resorts. It would be convenient and cheaper than renting a car.

However, most Westerners visiting Japan don’t book a ski holiday in typical fashion, like in the U.S. and Europe. Usually, the idea is to ski as much powder as possible, often driving around depending on where storms are hitting. Moreover, while there are over 500 ski resorts in Japan, most are quite small. It’s more enjoyable to experience several different areas rather than spend all your time in one place.

Public transportation does access many resorts, even the smaller ones, but there are so many little advantages to having a vehicle:

- Chasing storms can involve traveling on little notice.

- Public transport is in Japanese, adding another layer of difficulty.

- It takes a lot of work to lug gear around on trains.

- You can stay outside the immediate ski area and commute in with a car, saving money on accommodation.

- Many smaller resorts (often the most authentic ones) won’t be accessible, or easily accessible, with public transport.

Tips for Car Rentals

Car rentals are affordable and straightforward in Japan. You MUST get four-wheel drive (or all-wheel drive). The mountain roads are perpetually snow-covered, with loads of hairpin turns.

On the subject of sketchy roads, you’ll be driving slowly much of the time. Don’t try to race to the resort, or you’ll end up off the road or worse.

You can bring your own ski rack to save money on a rental. People often pack a foam rack in their luggage and attach it to whatever car they rent in Japan. Rental companies usually don’t offer racks or, if they do, charge extra for them.

A few other things to keep in mind:

- You need an International Driver’s Permit to drive in Japan. These are generally inexpensive and readily available in Western countries.

- There is a ZERO tolerance for drinking and driving in Japan. If you’ve had any alcohol, you cannot drive.

- Like the United Kingdom, Japan drives on the left side of the road with the steering wheel on the right side of the vehicle.

Japan Climate and Weather

Japan’s climate is fascinating for many reasons. These Pacific islands feature four spectacular seasons, each famous in its own right. For example, the spring bloom of cherry blossoms has long attracted locals and visitors and even has its own name: Hanami. But we’re here to talk about winter, of course.

Winters in Japan are among the snowiest on earth: the totals in Hokkaido resorts often surpass 15 m (600 in) per year; however, the vast majority of this snow falls between mid-December and the beginning of March. The snowfall is relentless for about ten weeks per year, making Japan Earth’s most reliable powder skiing destination.

Japan is so reliable for powder because the mechanism for snow creation is much different from any other mountain region in the world (that I know of). It works like this:

- Cold, dry air amasses over the Siberian tundra.

- The west → east flow of weather eventually brings this cold air east.

- The cold air passes over an unfrozen and relatively warm Sea of Japan. The air gathers moisture from the sea.

- The cold air now has plenty of moisture. When it hits the mountains of Japan, the air is forced to rise, cooling further with moisture condensing into snowflakes.

- This process continues all winter - or as long as cold winds flow from Siberia - because the Sea of Japan never freezes.

- Oh, and the Siberian air mass contributes to the dry snow quality.

Arctic air arrives with relentless wind. Above the treeline, it’s often too stormy to do much skiing. Nearly all the resorts are below treeline, though some offer cat skiing operations that top out a bit higher now.

Japan’s Snow Season

Japan's snow season is also different than other ski areas you may be familiar with. January (Japan-uary, for those new here) and February are THE months to go. It’s not worth flying across the world to ski here in December or March.

The skiing is good to go as soon as the Siberian winds have kicked in for a couple of weeks. The snow usually flies non-stop until the end of February, but after that, it’s like turning off a firehose. The arctic winds die out, and spring skiing commences immediately.

Japan is actually quite far South; Shiga Kogen and the resorts around Tokyo are at the same latitude as Las Vegas (36°N). The resorts here reach a maximum of about 2,500 m (8,200 ft), but the base areas are lower, and most resorts don’t have lifts going that high.

Meanwhile, the Hokkaido resorts are perched at a modest 42°N - on par with Jackson Hole or the Pyrenees - but have little to no elevation. Most of these resorts start near sea level, and the highest, Asahidake, reaches only 1,600 m (5,200 ft).

The southern latitude, moderating influence of the Pacific, and lack of elevation shut down the powder skiing pretty quickly around here once the arctic winds run out of steam.

Japan Ski Terrain

With over 500 ski resorts, Japan has a lot of different types of terrain on tap. You can find almost anything here, especially hiking in the backcountry. Nevertheless, most resorts share some key characteristics.

Trees

Trees, trees, trees. They’re everywhere in Japan. If you don’t like skiing trees, don’t come to Japan, it’s that simple.

The forests here are enchanted, literally and figuratively. Literally, because they are home to spirits, which the Japanese prefer not to disturb. That’s one of the reasons you’ll rarely see Japanese locals skiing off-piste, with many resorts roping off tree runs and calling them out of bounds (I feel like this is getting less common, though). The forests are home to creatures like the Kamoshika and, in Nazowa, the Japanese macaque, or ‘snow monkey.’

These exotic birch forests - a complete departure from the pine forests of many ski areas in the rest of the world - are figuratively enchanted as well. The birches grow open and well-spaced as if inviting a skier into their mystical lair.

The birch forests make skiing possible on 80% of days when the snow and wind are relentless. The storm’s fury tempers to a whisper as flakes flutter between the branches, sticking to everything along the way. The trees become white skeletons amidst a frozen world.

In 2012, Chad Sayers and Jordan Manley traveled to Japan for an episode of “A Skier’s Journey,” a series about skiing across far-flung corners of the Earth. Even though it’s old at this point, the episode (and the series) remains one of my favorite pieces about JaPOW.

Gullies and Runouts

Watch out for gullies and runouts. These terrain features are abundant in Japan and can ruin your powder day. Sometimes, it can take what seems like hours of strenuous exercise to work your way out. If it’s hard getting out, it usually means it’s a good day out there.

The resorts in Japan aren’t huge, but if you’re heading there for the first time and traveling around, you’re bound to get stuck here and there.

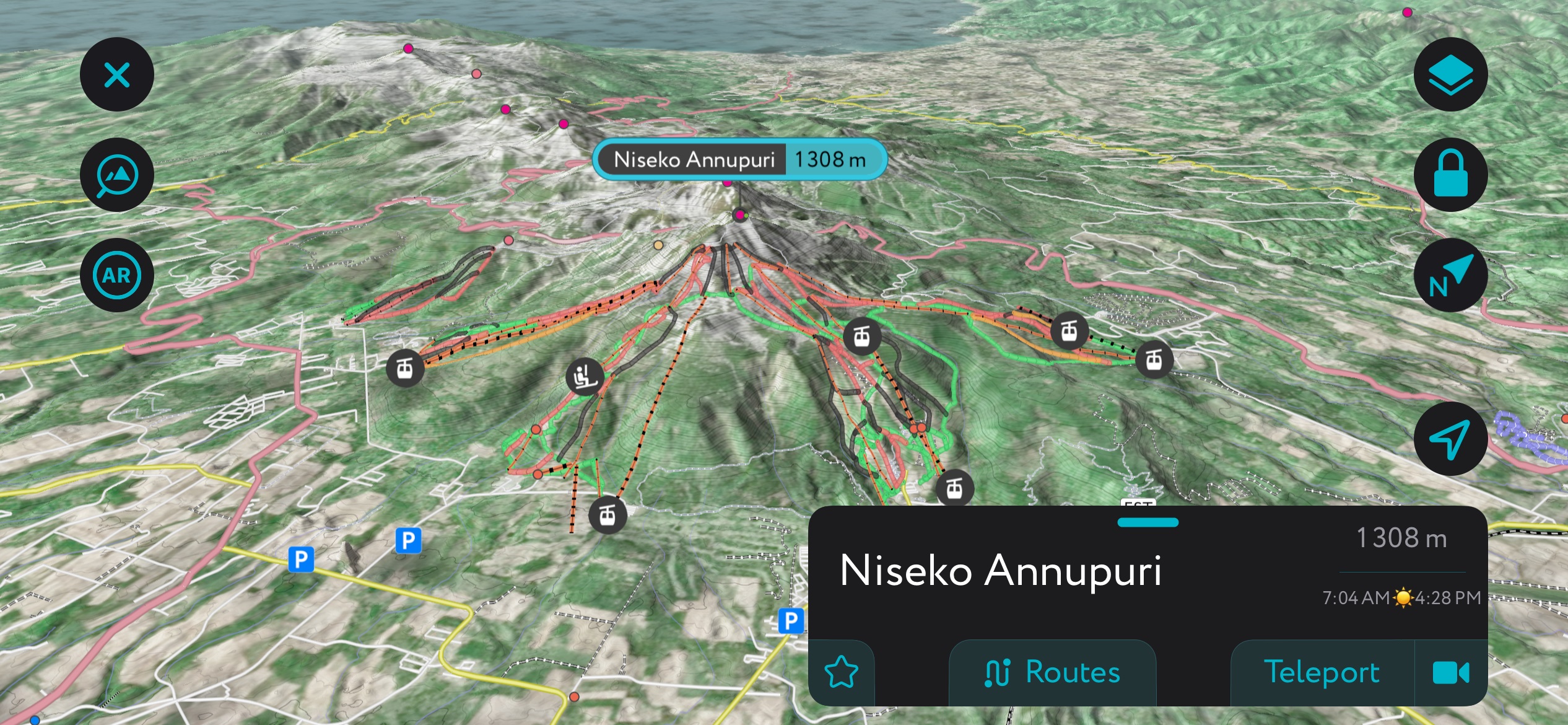

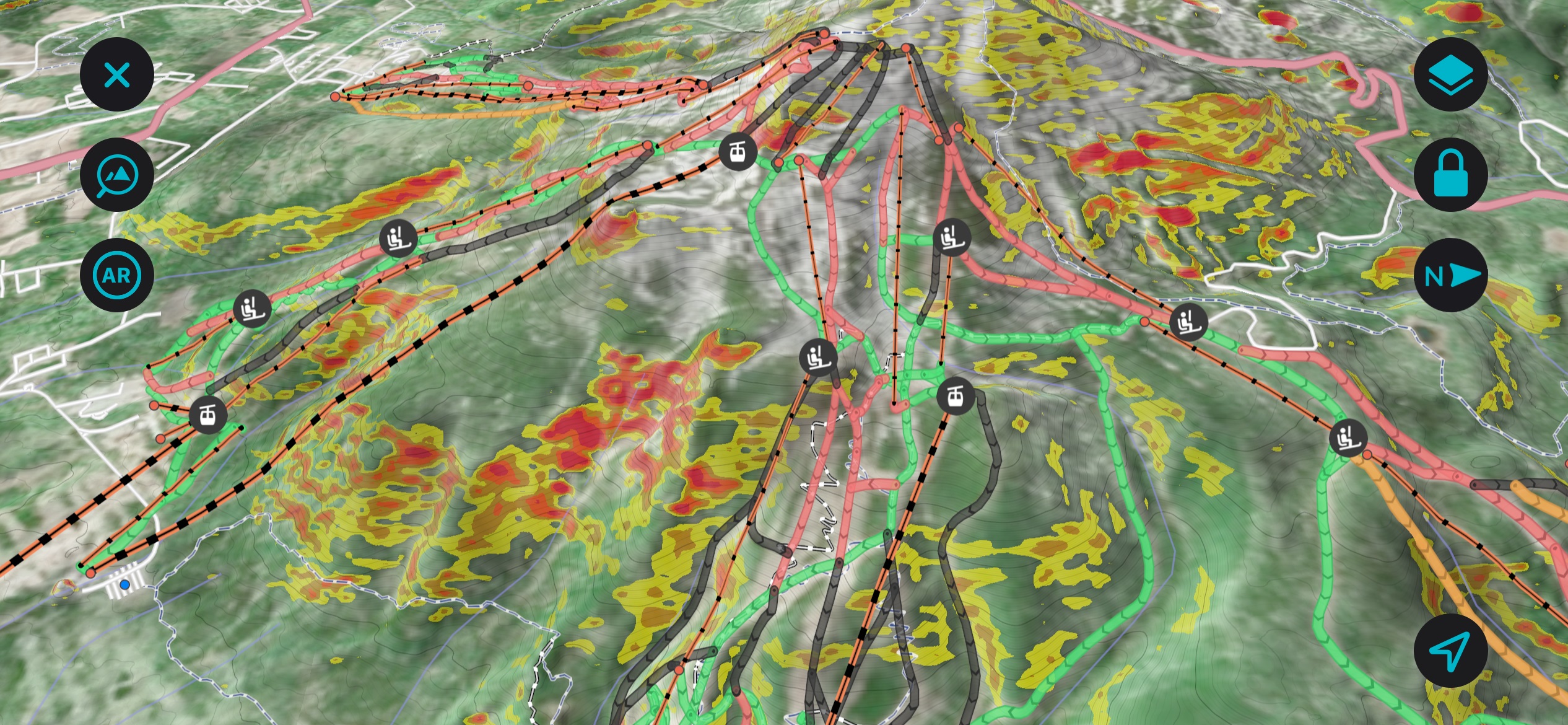

You can also use the PeakVisor app to scope out the terrain.

Mellow Slope Angles

Most Japanese ski resorts are not particularly steep. You’ll find steep shots here and there, but the slope angles are usually quite mellow, in the 15-25° range. In the U.S., I would compare them to Steamboat or Deer Valley.

Extreme skiers might get bored, but these mellow slopes are perfect for ripping a tree run with no brakes. It’s just that feeling of floating through powder, going exactly the speed you need to be going.

You can use the PeakVisor app to check out slope angles on your smartphone (although many of the slopes will be in the <30° category, which isn’t color-coded). You can either turn on the slope angle layer to see the angles of an entire region or select one specific coordinate.

Who Should Ski in Japan?

I’ll admit skiing in Japan is not for everybody. The weather is nearly always characterized by snow, wind, and whiteout conditions on the slopes. It can be viciously cold, the result of those Siberian winds that draw moisture from the Sea of Japan and deposit it in the mountains in the form of cold smoke powder snow. Moreover, there isn’t much steep terrain, so extreme or big-mountain skiers accustomed to the massive faces of Europe or western North America may be underwhelmed.

You should consider skiing in Japan if:

- You’re interested in skiing deep snow, even in bad weather.

- You like skiing trees.

- You like food.

- Honestly, this is probably the most crucial element: you’re interested in a ski trip that is as much a cultural exploration as a ski journey.

You should probably pass on Japan if:

- You want to ski extreme terrain. Believe it or not, I’ve met skiers who have poo-pooed their trip to Japan, complaining that it was flat and not exciting skiing.

- You’re looking for Western standards of luxury (although I suppose they can be found, especially in Niseko / Shiga Kogen).

- You want to ski in good weather.

Best Japan Ski Resorts

JaPOW is home to over 500 lift-access ski resorts and countless more volcanoes and mountain passes that serve as stomping grounds for backcountry enthusiasts. Many of these are minuscule operations that neither of us will ever hear of, while others have become international household names (amongst skiers, that is).

With such an array of choices, choosing the ‘best’ is always a fool's errand. It will always depend on snow conditions, terrain preference, or whether or not you like onsens. Maybe there’s a ryokan (guesthouse) out there that gives you an unparalleled feeling of content at the end of the day. Or an izakaya (intimate food and drink establishment) with a cozy atmosphere and the best chicken skewers you’ve ever had.

Westerners continue to make the pilgrimage to Japan each winter in greater numbers, so many places that were once completely unknown have now been ‘discovered.’ Still, here are a few ideas of places to check out; some are famous, while others are off the beaten path for a more authentic experience.

Hokkaido Resorts

Hokkaido is the powder Mecca of Japan. It’s Japan’s north island and receives higher quantities of snow than Honshu. The snow is also, on average, much drier than in Honshu, although both regions get relatively light snow. There are fewer ski resorts in Hokkaido overall, but there are still enough areas to spend an entire season exploring, especially when you factor in the backcountry.

Rusutsu

Like many places, Rusutsu used to be more of a secret. Now, it’s on Vail Resort’s Epic Pass. It’s great for Epic Passholders; if you use all five of your free days, you’ll save a couple hundred bucks at the ticket office. The flip side is that it’s more crowded here now than it used to be, namely with Westerners (Epic Passholders) looking to ski powder.

Still, there are several reasons people come here besides free passes. First and foremost, you’ve got the 14 meters of dry Hokkaido powder that falls between late December and early March. The tree skiing is easy to access from the lifts and is decidedly incredible. Moreover, you’ve got a mix of Western and traditional Japanese amenities at a range of prices.

It’s also a large resort by Japanese standards, so you could feasibly spend five days here during a big storm cycle, skiing fresh powder every day. Without the nightly refresh cycle, it would probably get boring for many folks.

Asahidake Ropeway

Asahidake is like the Silverton or La Grave of Japan. It’s not for everyone, but if you’re looking for no-frills skiing in Hokkaido, Asahidaki is the spot.

Despite the name “ropeway,” it’s a cable car that accesses the ski terrain. The skiing is proximate to an active volcano, and you can sometimes smell the gases escaping from the earth.

As you might have gathered, this area is best for those prepared for a ‘lift-access backcountry’ experience. It may seem like the powder in the immediate vicinity of the cable car is pretty chewed up, but the rewards lie for those willing to venture further afield.

Of all the places in Japan, Asahidake is where you would most want a guide - even if you’re an expert skier. It’s not that the skiing is particularly challenging, but that the route-finding and flat runouts can be vexing. Snowboarders are less likely to enjoy the terrain here on account of the long traverses getting back to the lift. The gullies and runouts can be genuinely treacherous; imagine trying to traverse out of snow up to your chest for a kilometer.

Last but not least, with all the volcanic activity, the place wouldn’t be complete without a few legendary onsens, would it?

Niseko

Niseko. I couldn’t write up a guide to Japan without including this gem. Although Westerners have overrun the place over the past decade or so, Niseko is still likely the best Japanese ski resort, especially by Western standards.

It has several modern base areas with plenty of Western-style accommodation and excellent food. But what really stands out is the extent of the ski terrain, which is on par with Western resorts like Steamboat or Big White. Most Japanese resorts are tiny, and while Niseko is not particularly large compared to Western resorts, it’s the biggest in Hokkaido.

Niseko offers endless tree runs, some of which are actually gladed (purposely thinned for skiing), and many pistes as well. The lift system is efficient, and you can clock lots of vertical in a day. The goods can get tracked out quickly on a bluebird powder day, but powder aficionados will covet those deep storm days that offer free refills all day in the birch forests (come to think of it, these days are much more common than bluebird days in Niseko). The snow totals are usually quoted at around 14 - 16m per annum (46 - 52 ft), most falling between Christmas and March.

The downsides of Niseko include the crowds, the lack of authentic Japanese culture, and, especially, the high cost. Niseko has collectively decided that, since it is the most Western Japanese resort, it will charge Western prices.

Honshu Resorts

Welcome to Honshu, Japan’s “main” island. Honshu is home to the vast majority of Japan’s ski resorts. The island generally receives less snowfall, and the snow quality can be denser (the exception being the Akita Prefecture resorts like Ani and Tazawako). However, the mountain ranges are more extensive, and there is a great diversity of terrain and cultural offerings.

Tenjindaira (Tenjin) Ski Resort

Like Asahidake Ropeway, the primary draw at Tenjin Ski Area is the lift-access backcountry skiing. In general, the terrain is much better than at Asahidake, but the weather is more fickle; big storm days can close the cable car for days at a time, whiteout conditions make most of the ski access impossible, and avalanches can roll through after snowfalls.

Nevertheless, if you hit it right, Tenjin offers the perfect combination of exciting terrain and deep JaPow. You won’t have to worry much about crowds, as the powder will always be there for those willing to hike.

Takaragawa Onsen, one of the largest in Japan, is nearby for those looking for a soak after skiing. You can also stay at the Ryokan here and commute to Tenjin.

Ani

Akita prefecture is not easily accessed, but those willing to put in the effort to get here will likely reap powder rewards. Ani is a classic Japanese experience; the small resort offers just a small area of skiing, with some lovely trees and pistes, but the true value is in the short ski tours from the top that open up worlds of off-piste tree skiing through the magical birch forests.

Don’t expect much in the way of good weather since Ani is the first obstacle for storms blowing off the Sea of Japan. Luckily, the forests offer plenty of contrast and protection from the wind. A guide could be helpful for those unfamiliar with the terrain or navigating Japanese forests and gullies generally.

Tazawako Ski Resort

Here’s the gem that opened my mind to the possibilities of Akita prefecture. Tazawako Ski Resort is a small, quiet resort in…well, the middle of nowhere. The lack of crowds and the frequent, heavy snowfalls make this a place worth exploring. While the terrain may not be legendary, the pitch is steep enough to enjoy some classic Japanese birch tree skiing with few other people.

Taza can get buffeted by winds during storms, and because the lifts are so slow, it can be a cold place to ski. Fortunately, there are onsens near the base area.

Nozawa Onsen

Whenever you see the word “onsen” in a resort’s name, you can be sure to have access to some healing hot waters after a day of cold Japanese powder skiing. That’s the case with Nozawa Onsen, likely Japan’s oldest ski town.

The town itself was founded in the 8th century when the onsens were discovered, and skiing was introduced by Europeans in 1912. The town, not purpose-built for skiing, still holds much of its charm; there are no high rises, and dozens of onsens are scattered throughout the village. You can find plenty of traditional ryokans and restaurants, as well as street food.

The skiing takes a bit of a backseat to the cultural presence of the town. The area, being in Nagano Prefecture (close to Tokyo), gets less snow than other resorts farther north. Nevertheless, it still gets quite a bit of snow (10m / 400in by many estimates). The terrain is not otherworldly compared to some of the other ski resorts on this list, which are featured on account of the skiing itself rather than the town.

Why You Should Explore Beyond Niseko

Niseko, located in Hokkaido, is the most famous Japanese ski resort internationally. It’s sizable by Japanese standards, has excellent terrain and tree skiing, and gets copious amounts of dry snow. Niseko was the place to go, say, fifteen years ago, before Westerners began flocking to Japan for powder skiing. Now, you can hardly tell Niseko apart from Australia.

I think half the joy of a Japan trip is in the cultural immersion: the food, onsens, ryokans, and new sounds of a foreign language. In Niseko, you get good lift access to well-spaced birch tree skiing, but you don’t get any cultural value unless you want to learn more about the culture of party-obsessed young Australians.

The best way to have this experience is to drive around to different tiny resorts out in the countryside and try your luck at a number of different places.

You’ll also save yourself a buck (or a few thousand of them) because Japan is actually quite affordable, although you wouldn’t know it if you only went to Niseko.

Lodging

More than other ski trips, where you stay is integral to the quality of a Japan ski trip. Is a traditional dinner served? Will you sleep on a tatami mat and futon? Is there an onsen onsight?

The gold standard of traditional Japanese lodging is the ryokan. During your trip, there is no reason to stay at any other lodging besides a ryokan or minshuku.

Ryokans are like Japanese refuges, often in onsen resorts or mountain towns, where traditional sleeping quarters are accompanied by dinner and breakfast. The food is usually of very high quality and is a selling point of the ryokan. Some Westerners may find themselves uncomfortable on a futon on a tatami mat (i.e., the ground) and opt for a Western-style hotel (more likely to find these in the more prominent ski resorts). Ryokans can be large or small, affordable or very expensive. In onsen towns, the ryokan will often have its own onsen.

Minshuku are like budget ryokan. They offer the same traditional Japanese lodging but are family-run and generally tiny. Like Ryokan, the food is the highlight; a stay typically comes with one or two meals.

Pensions are like minshuku but with Western-style sleeping arrangements. There are also Western-style dorm hostels for those on a budget.

Western hotels have inevitably cropped up as Japan becomes more of an international tourist destination. You can find capsule hotels in urban areas like Tokyo for the ultimate economy lodging, but they’re far less common in ski towns. Naturally, vacation rentals are also an option through the usual venues (Airbnb, VRBO).

Dining

Japan is celebrated for deep powder skiing, but it is even more renowned amongst the general population for its extraordinary culinary culture. The late, great Anthony Bourdain proclaimed Tokyo the world’s finest food hub, which is no small statement considering he’s been everywhere. And then there’s Jiro, the Sushi master dedicated solely to perfecting his craft; the man defines the spirit of Japanese perfection like no other.

You - or a reluctant, non-skiing spouse - could fulfill an entire trip to Japan just with culinary experiences, even in mountain towns.

Much of the action takes place in izakayas; these cozy, intimate establishments serve a variety of food and drink. Japanese drinking culture is also rich, with sake, beer, and domestic whisky being prominent specialties. Mountain town izakayas are often historic, having existed for decades or even centuries in the same spot. Food is generally served on shared plates; dishes typical of the mountains are the classic wagyu beef, hot soups like miso and ramen, soba noodles, and vegetables. Of course, there is also cooked and raw fish galore, although sushi (raw) is less popular than in the coastal cities as the Japanese cherish freshness.

Onsens

Many towns and ski resorts in Japan are built around natural volcanic hot springs called onsens. Resorts often include the word onsen in their name if they are present, i.e., Nozawa Onsen and Seki Onsen.

Onsens are one of the most magical aspects of Japanese skiing. Onsen culture goes very deep, and many onsen towns are thousands of years old. The hot water is often diverted around the town, with hot water pools at hotels, guesthouses, and public bathhouses throughout the central area (Nozawa Onsen is a perfect example). Onsen towns are especially associated with ryokan, or Japanese communal guesthouses.

Traditionally, onsens are enjoyed in the nude, with men and women separate. However, a higher volume of foreign tourists likely means that you can find more exceptions to these rules than before. Many onsens are available to both men and women now.

The Jigokudani Snow Monkey Park features snow monkeys that bathe in the onsens in the wintertime, although you won’t have any of these red-faced visitors in your local onsen.

Gear

Due to Japan’s extreme winter weather, skiers sometimes don’t realize what they will need from their gear. Here are the major boxes to tick before you head over.

Low-light Goggles

Goggles are the pieces of gear that most commonly fail to rise to the challenge in Japan. Most skiers ski with goggles that have a reasonably high degree of light protection, which is great for any amount of sun at high-altitude resorts in Europe and western North America. In Japan, however, Mr. Sun rarely makes an appearance between December and March. Especially in Hokkaido, you’re looking at weeks on end of snow and wind.

That’s why it’s essential to bring low-light lenses on your trip. It makes a world of difference on those stormy, low-visibility days. Clear lenses work great. Another word to the wise would be to bring multiple pairs of goggles, as a single pair can often get wet and fogged up throughout the day.

Gore-Tex

Skiers love to boast of their Gore-Tex - or other waterproof - gear, but few have genuinely put this gear to the test. Japan is the place to see just how waterproof your pants and jacket really are. Jackets with powder skirts and mittens that cinch around the wrist are a must to prevent sneaky snow.

Avalung

An Avalung, a device originally designed to allow people to survive longer if buried under an avalanche, can also be useful in Japan. Japan is the only place I would consider using one of these. While the chances of getting buried in an avalanche are relatively low in Japan (compared to Europe and N. America), the Avalung is helpful because it serves as a snorkel when the snow is so deep that it's tough to breathe while skiing. A regular old pool snorkel works as well. It can also be useful for getting stuck in tree wells (not many in Japan; they don’t have many evergreen trees) or just wallowing around in snow after a fall.

If you don’t have a snorkel, try breathing through your teeth or a buff to prevent choking on powder.

Fat Skis

Fat skis are essential in Japan. It’s really the only place where something 140 underfoot would be useful more than one day out of the season. If you don’t have anything that fat (don’t worry, neither do I), think about renting a pair to try it out. Skiing such deep powder with two snowboards under your feet is an incredible sensation.

Bringing Your Skis vs. Renting

Most expert skiers from North America or Europe would scoff at the idea of renting gear from a shop. Honestly, it could be the call in Japan for a few reasons:

- There are plenty of great ski shops, and the Japanese take pride in their service (the experience is painless now that we have translation apps). Unlike the endless array of piste skis you’re used to seeing at rental hubs, the right shops have high-end powder setups.

- Most people don’t have skis wide enough for deep days in Japan.

- Hauling skis will add about 200 USD roundtrip to the cost of your flight (unless you can fit all your other gear in your ski bag and are going to check a bag anyway).

Touring Kit

The best skiing in Japan often involves some kind of manual ascent on top of a lift ride. While you could boot it…you probably don’t want to be doing that in a meter of snow. Having touring bindings and skins is a monumental advantage in the quest for powder here (as it is anywhere these days). CAST is my go-to kit for lift-access backcountry tours that are less than an hour or two.

Hiring a Guide in Japan

Some skiers enjoy the experience of skiing with a guide wherever they travel, while others prefer to approach the adventure on their own. Both approaches are perfectly valid. In Europe, for example, much of the best off-piste skiing involves aspects of mountaineering, like glacier travel, that many people don’t have adequate training for. Hiring a guide not only helps with finding the best snow but adds a critical element of safety.

The reasons for hiring a guide in Japan differ from those of a big mountain destination like Europe or Alaska. There are no glaciers in Japan, nor is there much in the way of alpine skiing. The terrain is not technically challenging, and most foreign skiers specifically traveling to Japan to ski are experts. Yet, there are several reasons why you may want to consider a guided trip in Japan, especially if you're coming for a shorter period:

- There are over 500 ski resorts in Japan, many of them tiny. Hidden gems abound.

- Weather patterns bring powder to different resorts at different times.

- The terrain is often a confusing network of forests and gullies. Getting caught in the wrong gully could mean an hour of wading through deep snow. You must know where to keep speed, slow down, etc.

- Some resorts allow off-piste skiing; others don’t. Some places enforce these rules, while others don’t. You could end up losing your ski pass.

- Everything is in a foreign language. There are specific routines for everything from buying tickets to loading lifts to parking that take time to figure out.

- Most of these guided trips arrange everything, including transportation, meals, and lodging, which all require some effort to figure out (once again, everything is a bit different here).

For these reasons and more, I’ve known many expert skiers who hire guides for their trips to Japan. Heck, I’ve known guides who have hired guides. It’s just easier to have someone who knows the ropes for both the skiing and the itinerary details.

There are dozens of guide companies to choose from; Hokkaido Powder Guides has a good reputation and excellent personnel (IFMGA certified). Be sure to investigate your guides thoroughly for appropriate qualifications and experience before committing to a trip.

Conclusion

Japan is not merely a vessel to ski legendarily deep powder snow but an ancient and unique mountain culture worthy of several lifetimes of exploration. Use this guide as an introduction. Then get out there and have an adventure, which will surely consist of as much of new friends, steamy onsens, and delectable ramen as it does deep powder and enchanted birch forests.