Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Nagaland (pronounced simply Naga-land) is a mountainous, landlocked state in the northeastern branch of India. Towering over the capital Kohima, Saramati Peak (3,840 m / 12,600 ft) marks the Naga Hills’ highest point. With its breadth of mountaineering options, incredible views of nearby Myanmar and Assam, and significant tracts of untouched forest, the state is an excellent option for those wanting to escape the crowds and thin air on more high-altitude Himalayan itineraries. No one really knows when and how the 20+ Naga local tribes came to inhabit this wild stretch of winding river valleys, rhododendron meadows, and montane rainforest, so you may just have to ask them in person. Known in India as the “land of festivals” for the world-famous Hornbill and Moatsu celebrations, Nagaland is emerging from its notorious headhunting past to be an ambassador of tribal-led ecotourism across the region.

Formerly a part of its western neighbor Assam, Nagaland also borders Arunachal Pradesh to the north, the Burmese Naga Self-Administered Zone to the east, and Manipur to the south. With just over 2 million people living on 16,500 km², Nagaland is one of the least and most sparsely populated states, at about 1/4th the Indian average population density.

For the most part, Nagaland’s territory comprises a gradually inclining hill country intersected by major rivers Doyang and Dikhu, as well as tributaries of the transnational Barak and Chindwin river systems.

In the northwest, the low-lying Brahmaputra river basin on the border with Assam lies close to sea level, whereas the southern and eastern portions of the state rise to 3000 m+ peaks in the Naga Hills (part of the Arakan parent range).

From the alpine bamboo meadows of the southern Dzukou Valley to the steamy, dense forests bordering Assam and snow-clad rock faces overlooking Myanmar, Nagaland’s geographic diversity rivals its tribal treasures.

Like its surrounding neighbors, Nagaland is a predominantly rural and underdeveloped region of India. Despite this, its medical infrastructure, paved road network, and relatively well-connected Dimapur airport make travel more convenient. Outside Dimapur and Kohima, however, Nagaland remains wild and rugged.

Alongside its 20% forest cover, soaring mountains, and navy blue river valleys, Nagaland boasts beautiful rice terraces. Nagaland’s rich soils and varied topography hold potential for thriving cash crops and hydropower generation, but for the most part, these resources remain underutilized. Slash and burn agriculture and wood-based heating remain firmly in place. As a result, the state remains a net food and power importer.

Nagaland’s geology tells the story of age-old plate collisions and metamorphic folding. Located near the epicenter of the Eurasian and Indian plate fault line separating India and Myanmar, Nagaland’s Arakan Range forms a subpart of the greater Naga-Patkai fold belt that spans from the Nicobar Islands in the Andaman Sea to the upper stretches of Arunachal Pradesh. As a result, its rocks are relatively young.

When the Indian and Burmese plates collided, they pushed up large amounts of oceanic crust, forming an intriguing mix of green ophiolitic rocks with basaltic influence. Like herniated disks, Nagaland’s mountains were squeezed out from the youngest metamorphic folding site in the world. Another prominent rock layer in Nagaland, called “Phokphur”, next to the ophiolitic/basalt formations, is easily distinguished by its oxidized, red-iron taint. Across the Naga Hills, these two formations come in regular contact, while in the more western and northern parts of Nagaland, alluvium, “disang”, and “barail” formations dominate.

Given its complex and evolving geology, Nagaland is rich in minerals, notably coal, limestone, and iron. Heavy metals like chromium, cobalt, and nickel likewise abound in the state’s mountainous districts.

Nagaland is part of an important ecozone, the Naga-Manipuri-Chin Hills Moist Forests. It is part of the greater northeast Indian region with its mountainous topography and lower population pressures. Its wealth of rivers and montane forest canopies makes for a species-rich ecology.

However, this ecology has been fundamentally altered and challenged by the ancient practice of jhum (slash and burn agriculture), plastic and sewage pollution of urbanized streams, and recent developments in petroleum and palm oil. Particularly on the Assam border, palm oil monocultures threaten to engulf the last remnants of primary jungle.

A large portion of what used to be primary forest now holds shrubs, bamboo, and other low-canopy regrowth over previously burned land, radically changing the water capacity and erosion containment. Modern plastics and rising populations have created a dangerous mix for local ecosystems.

Nagaland’s mixed deciduous forests, particularly those altered by agriculture, stand vulnerable to drought during the dry season. More extreme monsoon onset likewise endangers mountain valleys from mudslides and flood events.

Nagaland’s climate is strongly monsoonal, with very warm, rainy summers and dry, cool winters. Summer (May through September) temperatures can reach 40℃, but usually hover around a tropical, humid 30℃.

Frequent showers cool off the sun-drenched valleys, particularly in the northwestern districts bordering Assam’s extremely moist Brahmaputra river basin. The southeastern districts are the driest, with some pine forests and cleared mountaintops turning very arid near the end of winter.

In general, winters bring cool temperatures of around 4-10℃, but Nagaland’s 3000 m+ peaks are no strangers to snow showers. Higher valleys can experience frost as well.

From mountain juniper, to dryland oak, to luxurious mahogany trees and some of the world’s highest rhododendrons, Nagaland’s forest diversity owes to its hot monsoon climate intersected with varied elevation.

In its lowest reaches, intact jungle still exists. This includes genuine evergreen forests, once the crown jewel of the Namsa-Tizit area, but now severely reduced to small tracts in the Zankam area in Mon District. If lucky, you will see old-growth, thick-trunked species like Hollong (Dipterocarpus macrocarpus) or Makai (Shorea assamica).

In Mokokchung, Wokha, and Kohima Districts, however, deciduous species like Bhelu (Tetrameles nudiflora) or Paroli (Stereospermum chelonoides) intermingle with the evergreens, forming a semi-evergreen jungle.

Moving further uphill between 500m and 1800m, all districts boast subtropical forests, primarily wet, broadleaf, and semi-deciduous, providing important timber species like Koroi (Abelmoschus), Pomas (Chukrasia), and Sopas (Magnolia).

Some microclimates in Phek and Tuensang districts host drier pine forests, mixed with species like oak. Above 2500m–such as in the Saramati and Dzṻkou areas, Nagaland’s forests are moist and temperate, with rhododendron, oak, birch, and juniper.

In areas covered by snow and frost, alpine dwarf forests, dominated by bamboo and rhododendron, thrive. Near the treeline, juniper krumholz fights for survival on Nagaland’s windswept peaks.

While Nagaland’s abundant forests house some of the common mammals present in neighboring Assam, such as tigers, elephants, sloth bears, and Indian bison, it is mostly known for its distinct bird species, such as the Blyth’s Tragopan (the state bird) and its many hornbills. Likewise, areas like the Doyang Reservoir cater to a wide range of migratory birds, most famously the falcon migration. As the traditional Nagamese diet suggests, the state also contains a diversity of fish that roam its montane rivers.

For the most part, Nagaland’s history remains a mystery, as the local tribes left no written records, and its mountainous geography inhibited major outside influence. Given the Nagas’ Sino-Tibetan languages, some historians argue that they migrated from Yunnan Province when the Great Wall of China was built.

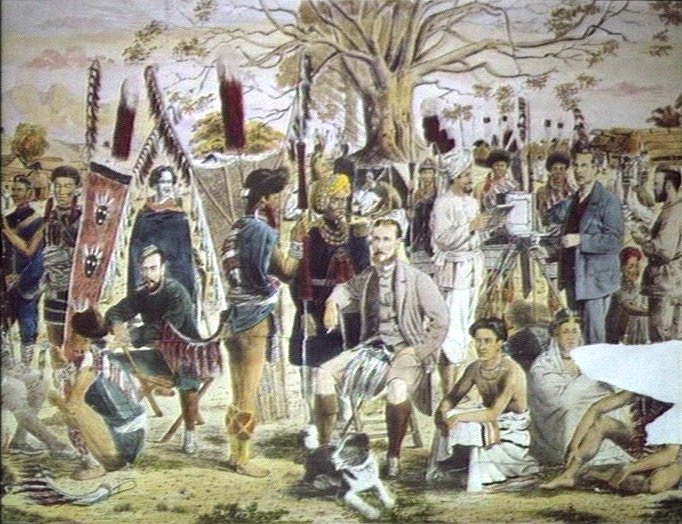

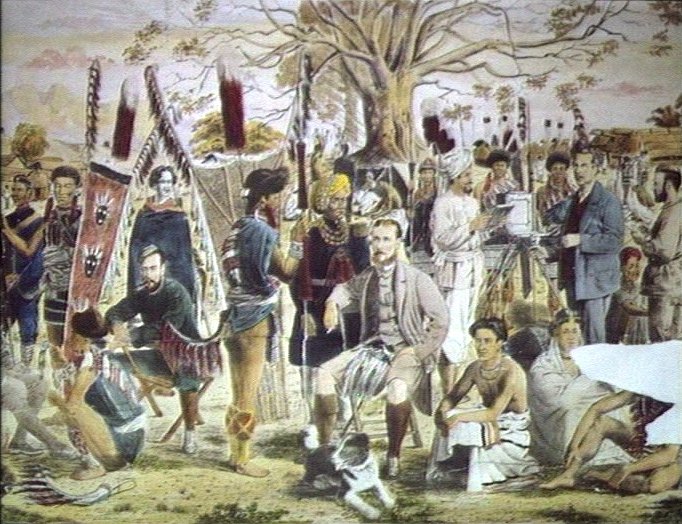

One of the first detailed accounts of the region stems from Austrian ethnologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf. Despite contemporary criticism for his unclear association with the Third Reich, he was among the first to document and preserve the Nagas’ sociolinguistic legacy in film and photographs in the 1930s.

Upwards of 20 tribes, from the autocratic, headhunting Konyaks in the north, to more democratic, benevolent groups in the south, farmed Nagaland’s verdant hills with jhum (slash and burn) agriculture. Traditional Naga customs emphasized merit, whereby young male warriors hunted enemy skulls and adorned their morungs (wooden dormitories involved in rites of passage) with them.

Other signs of merit included hosting large feasts, as well as gathering sexual experience. The western guise may focus on the widespread slaughter and patriarchy, but some anthropologists regard the Naga as comparatively egalitarian, in large part due to the gender-equalizing dependence on nature. Reliance on animist beliefs instead of Hinduism likewise prevented the establishment of historical caste systems.

In spite of their tribal autonomy, the Nagas faced increasing bloodshed fighting off the Assamese Ahom Kingdom in the 15th-16th centuries. In the early 19th century, the Burmese briefly controlled the modern-day state.

However, it wasn’t until 1944, when the heavily armed Japanese invaded Burma, that the Nagas faced a dire threat. In the famous battle of Kohima, sometimes referred to as “Britain’s Greatest Battle,” Indian, local, and British forces defeated Emperor Hirohito’s armies that were bushwhacking their way through Southeast Asia towards India.

Nevertheless, the relationship between the British and the Nagas was anything but friendly. For years, Assamese tea plantation “lords” fought against the tribes, until the central Indian government sent troops to intervene. Meanwhile, Baptist missionaries sought to convert them and eliminate their headhunting practices.

Nagaland was officially recognized in 1963, but guerrilla warfare and violent independence movements tainted the state’s reputation into the 21st century. However, relative peace has been achieved, despite some scattered tensions. The Naga stand proud of their traditions, although morungs now display artwork instead of skulls. Headhunting, in fact, is now locally seen as a dark chapter deserving collective shame, rather than pride.

Given its tribal culture, Nagaland naturally emphasizes preserving the fragile synergy between its peoples and their lush forests. According to the national forest department, there are 407 community conserved areas (CCAs), with almost 85% self-initiated by tribes.

In addition to these informal conservation schemes, as well as local agroforestry, the state has gone further to officially protect key wildlife zones with one national park and several sanctuaries. Intanki National Park, located on Nagaland’s western edge of the Barail Range, is known primarily for its dense, moist forests that house Hoolock gibbons and golden langurs. The renowned Hornbill also roams these parts. Rangapaha and Puliebadze Wildlife Sanctuaries lie north and east of Intanki, respectively. Further east, on the border with Myanmar, Fakim Wildlife Sanctuary is yet another wildlife hotspot.

In the Angami’s Viswema dialect, dzükou roughly translates to “soulless and dull,” but this description has a primarily agricultural origin. In fact, some point to the Angami/Mao word that translates to “cold water”, referring to the valley’s freezing mountain streams.

Just southwest of central Kohima, Dzükou is a 2-4 million-year-old geosynclinal valley formed by unique weathering patterns.

The 2452-meter (8045-ft) area looks like a green crater-scape linking 27 km² of verdant, contoured folds and steep ravines. During its amazing sunsets, scorched black tree trunks, Christian crosses, and endless expanses of dwarf bamboo colonies light up with deep orange tones.

In the spring and summer, locals call it “the valley of flowers,” as species like the Dzükou lily (Lilium chitrangadae) blanket entire mountainsides. In the molds of its steep gullies, remaining forests concentrate around seasonal streams, with opportunities to view Blyth’s Tragopan while brushing through ferns and mossy corridors. You may even spot the odd cherry tree! Just make sure to wear long socks to avoid the infamous blood leeches.

Accessed via a 2-day trek from Viswema Village, or via the Zakhama Trail, Dzükou Valley also offers access to Nagaland’s and neighboring Manipur’s prime hiking terrain, including Mt. Japfu (3048 m / 10000 ft) and Mt. Iso (aka Mt. Tenipu) at 2994 m (9832 ft). Near the western portion of the valley, Sanctuary Fall, a wintertime waterfall that freezes, is likewise worth a visit.

While the valley's upper reaches are indeed agriculturally “barren”, the surrounding lower-altitude settlements host some of Nagaland’s most ecological agroforestry, including the Angami practice of pollarding alders.

Nagaland’s Mt. Saramati and surrounding high terrain are not for the faint of heart. Distances in the small state are generally manageable, but just getting to Thanamir Village—famous for its juicy apples and home to the mountain’s mandatory guides and porters—is an adventure in itself. Hire a “sumo” SUV vehicle to get from Dimapur to Pungro, and from there, brave the roads to Thanamir.

Once there, a weathered Christian settlement, with some 150 households, hugs the base of Saramati’s approach. Local children are known to stare, and communication may require a good dose of gesticulation.

You will be offered black tea to warm up, accompanied by spartan rice and dal dishes. Once you procure a guide and porters, navigate moist forest trails and rock faces to the forest basecamp, where the summit lies within reach. Located at the eastern portion of the Kiphire District, the summit provides incredible views of nearby Myanmar.

For the adventurous, Nagaland is home to many unexplored peaks. The range near Saramati contains several high summits, such as Mt. Khuelio King (3462m / 11358 ft). Some local missions have sought to approach and ascend, but have turned back. Accessible via Choklangan or Wui Village, the road conditions to reach its base are filled with potholes that can turn into streams during monsoon. Unlike at Saramati, there is little supporting infrastructure to accommodate mountaineers. Those that do venture, however, will be rewarded with supposedly some of the most beautiful mountain ebony, mulberry bushes, and untouched forest below.

While this mountain can be approached indirectly after a trek through Dzükou, Mt. Japfü is best explored via Kigwema Village from the Japfu Christian College road in the Kohima district of Nagaland.

Although less intense than Saramati, being around 800 meters lower, the ascent does require rock climbing skills to ascend two steep walls near the peak. Keep an eye out for—apparently—the world’s tallest rhododendron tree. Near its twin peaks, in the 2000-3000 meter elevation zone, unique moist montane canopies appear and disappear under the frequent cloud cover.

Other mountains to check out, with less committed hiking or camping required, include Mt. Tiji (1970 m / 6463 ft), Mt. Kapamüdzü (2620 m / 8596 ft), and Mt. Pauna (2841m / 9321 ft). These can be ideal for those who want to experience wildflowers and skip the cold.

While the Naga have many cultural treasures on offer, some of them can be hard to experience as a foreigner, given the many tribes spread across various mountain valleys and some language barriers.

Perhaps the easiest entryway into Nagamese culture is the Hornbill Festival. In 2000, the Government of Nagaland kickstarted this world-renowned celebration to encourage inter-ethnic interaction and to promote the state’s cultural heritage, named after the hornbill bird.

For ten days in early December, Kisama Heritage Village illuminates with colors, including traditional Naga morungs showing off their crafts, food delicacies, and herbal remedies. From beauty contests, archery, naga wrestling, and Naga King Chilli eating competitions to western-influenced WW-II Vintage Car rallies, this smorgasbord of cultural activities has about anything a brash young reveler could desire. The festival is so beloved that some elderly visitors are flown in via helicopter, as the roads to the remote village can be hard to traverse.

Dimapur is Nagaland’s largest city, home to the second-largest railway station in northeast India. Unlike Kohima and the surrounding areas, Dimapur offers a more modern feel, home to a 40% Hindu population from various parts of India. Although the 2004 Islamic terror bombings left a somber mark, the city is a safe and interesting place to visit.

When in town, make sure to visit the centrally-located ruins of Kachari Rajbari, home to ancient monoliths, pillars, and domes dating back to the 10th–12th century Dimasa Kachari Kingdom. The Dimapur Jain temple, intricately preserved with its impressive glasswork, is likewise a must-see.

If in town with kids, stop by the Nagaland Science Centre and end the day at New Market & Super Market. Dimapur’s markets are excellent places to experience Naga life, food, and textiles. Mouthwatering smoked pork with bamboo shoot, or akhuni (fermented soybeans), are just a few of the delicacies you will hear street vendors advertise through wafts of BBQ smoke.

If you have a car, take a short trip to Diezephe Craft Village, an incubator for artisan talent just outside the city, cranking out impressive handloom and woodwork. Equally close is Nagaland Zoological Park–a large, green reserve housing local and endangered wildlife species with a familial ambience. If you want to combine a light trek with a waterfall view, Triple Falls near Seithekema Village offers a hidden gem with three distinct cascades about 30-40 minutes from Dimapur.

Kohima is truly Naga. If visiting in early December, the Kisama Heritage Village will be the first stop for an immersion in all things Naga at the famous Hornbill Festival, accompanied by a pint or two of local rice beer.

Like Dimapur, Kohima has fantastic outdoor opportunities at its doorstep, from the famous “green” Khonoma Village, known for the local Angami’s emphasis on ecotourism. In peak season, it may be even better to visit Tseminyu & Rengma Villages, offering an unknown, off-the-beaten-track experience.

If directly in town, the Kohima War Cemetery and the Nagaland State Museum are great ways to soak in the history and culture of Nagaland’s capital. After lunch at one of the food stalls dishing out smoked pork and bamboo shoot curry, some refreshing orange juice, and a digestive coffee, finish off the day with a climb up Aradura Hill to visit the Catholic Cathedral (Mary Help of Christians Church), a beautiful cathedral overlooking central Kohima.

Explore Nagaland with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.