Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Haryana (pronounced har-ry-ana) is a landlocked state in northern India, forming the entryway into India’s semi-arid, northwestern breadbasket. Although primarily an agricultural plain, Haryana does rise to 1467 meters (4813 ft) at Karoh Peak in the Shivalik foothills, with awe-inspiring views of hazy southern horizons and snow-capped peaks to the north. Carved out of Punjab in 1966, Haryana lies in the west of the fertile pre-Himalayan floodplain, home to India’s most densely populated areas. Although it’s more an emblem of India’s Green Revolution than a hiking destination, Haryana offers Indian weekend travelers a convenient getaway to escape the urban jungle of the NCR (National Capital Region). Its strategic location between Delhi, the Himalayan foothills, and the rich desert treasures of Rajasthan makes Haryana worth a visit.

Haryana’s 44,212 km² territory spans 27-30°N latitude, with significant portions of the state elevated above 400 meters. However, the only true “mountains” exist in the northeastern Morni Hills and the Kalesar area bordering Himachal Pradesh, reaching upwards of 1000 meters and intersected by rugged, monsoonal streams.

The southern border shared with Rajasthan is home to some isolated Aravalli hills. Still, millions of years of erosion have crumbled this ancient mountain range to dust and pebbles, at least in Haryana’s portion.

Haryana’s western districts become drier and sandier as they approach the Thar Desert in neighboring Rajasthan. It is here where the seasonal Ghaggar river flows, said to be a remnant of the mysterious Sarasvati river that disappeared, decimating early agricultural civilizations.

To the east, the Yamuna River, a vital agricultural artery, divides Haryana from Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, reaching the state's southeastern corner. Here, Haryana forms a horseshoe-shaped boundary around the national capital.

The largest portion of the state, however, consists of endless alluvial plains (central and eastern Haryana) crisscrossed by rivers like Yamuna, Ghaggar, and Markanda. Given the rich loamy soil, roughly 80% of Haryana’s land is devoted to agriculture, particularly wheat, rice, sugarcane, cotton, and mustard. The remaining tree cover, outside small patches of green canopy in Kalesar and Morni Hills, tends to be dry, thorny shrubbery that thrives in the semi-arid southwest.

Haryana’s geographic location in northwest India is a gateway between the national capital and the northern Himalayan states. The dense network of roads and railways—forming part of the regional “Golden Quadrilateral”—makes travel and commerce incredibly efficient.

Haryana can be broadly divided into three geological regions. The first are the Precambrian Aravalli Hills in the south, which boast ancient metamorphic and igneous rocks like quartzite, schist, granite, and gneiss, and were formerly recognized as part of the so-called “Delhi Supergroup.” The Aravallis are home to extinct volcanoes like Dhosi Hill. In ancient times, societies mined iron and copper in the Aravalli Hills, but today the ores are not of commercial value.

North of the Aravalli, the Quaternary “Indo-Gangetic Alluvial Plains” (northern and central Haryana) are rich in unconsolidated sands, silt, and loose rocks deposited by rivers. This makes for productive soils coupled with groundwater-rich aquifers.

Traveling even further north, these plains end in the Shivalik foothills, an active seismic zone home to Tertiary conglomerates, sandstones, and clay formations. This zone is even home to some vertebrate fossils.

Despite significant steps toward nature and wildlife conservation, Haryana faces serious pollution challenges due to its largely agrarian and industrial land use. Only 3.6% forest cover remains, concentrated in the northeastern hills’ Sal tracts.

Particularly, the southeast around New Delhi sees immense population pressure and industry runoff threatening local wildlife areas. Eco-sensitive zones have been erected to limit construction surrounding the already fragmented habitats, but recent developments, like the alleged Yamuna river mining, question the strength of such government mandates.

Like neighboring Punjab, Haryana’s dry plains are at risk of drying out, as the selection for water-intensive hybrid seeds has reduced water tables to critical levels. Various afforestation efforts and a call for more produce farming seek to counter this trend.

The most acute issue, however, remains air quality, as stubble burning—an age-old practice to re-flatten grain fields—creates India’s and some of the world’s worst air quality in the post-harvest months. Despite all this, those who know where to go will find some preserved natural wonders.

In its westernmost extremes, Haryana’s climate approaches that typical of a subtropical desert. Numerous factors, such as the drying of the ancient Sarasvati river and the rain shadow of easterly monsoonal winds, explain this pronounced aridity.

In May and June, the scorching Loo winds bring dry blue skies with daily highs reaching 47°C (117℉). From July to September, a brief monsoonal period lets some hilltops regrow their brown grass. Temperatures hover around 25-35°C, with frequent intense rain showers, especially in the northeast.

Annual rainfall varies dramatically, with Haryana’s western regions receiving 4 times less rainfall (only 300 mm) than the northernmost stretches of the Shivalik foothills. While temperatures decrease after June, the incredibly high humidity makes for sticky conditions. Bringing a change of clothes in the summer is highly advised!

Post-Monsoon, (October to November) is probably the best time for hiking and is also a peak agricultural season, with 20-30°C days and limited rainfall. Haryana’s relatively high latitude and aridity make for chilly, continental-influenced winters. December to February brings 4°C nights and 20°C days, with some rural plains experiencing frost. The Shivaliks in the north likewise experience colder temperatures.

Being a hazy plain, most mornings are draped in thick fog in the depths of winter. Despite government crackdowns, the local practice of burning harvested rice and wheat fields can make air quality a serious issue throughout the state starting in November. Asthmatics, be advised!

Though a relatively small agricultural state, Haryana hosts diverse flora and fauna due to its varied landscapes, ranging from the Shivalik Hills in the north to the Aravalli range in the south and plains in between.

For example, the southwest contains shrub and thorn forest, while the north boasts subtropical, dry deciduous tree species. However, the planting of non-native pines and other fast-growing species has strongly altered their natural habitats. The only dense, native Sal forest remains near Kalesar National Park.

Other than that, scattered trees line quadratic patchworks of rice fields, including north Indian rosewood, neem, acacias, and other species typical of the north Indian plains. Near religious sites, the branching Bodhi tree is held in high regard.

In Haryana's western and southern stretches, low precipitation, sandstorms from the Thar Desert, and generally arid conditions limit vegetation to scattered shrubbery. This includes species like Carissa, Capparis, and Calotropis. Wild Saccharum and sand spurs cover the uncultivated flatland.

Haryana is not the best state for those eager to spot large mammals. Some elephants exist in Kalesar National Park, but Haryana’s wildlife diversity is limited overall. The most widespread large mammal is the Nilgai (Blue Bull), while in less populated areas, Indian Hare, Wild Boar, Jackal, and Indian foxes abide. Near Gurugram and Faridad, the occasional leopard spotting occurs, but for the most part, they roam the Aravalli hills on the more untouched Rajasthan side. Even outside designated nature areas, chance encounters with cobras, vipers, and bullfrogs are not out of the question.

Seasonally, Haryana also becomes the stopping point for many migratory birds, in addition to the resident species. In some wetlands, greater flamingos and common teals can be spotted in winter.

Haryana’s documented history began with the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1300 BCE), with sites like Rakhigarhi (Hisar district) home to Harappan archeological remains. During the Vedic Period (c. 1500–500 BCE), the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms ruled. Notably, near Kurukshetra, the legendary Battle of Kurukshetra saw Arjuna talking to Lord Krishna, as recited in the holy Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita.

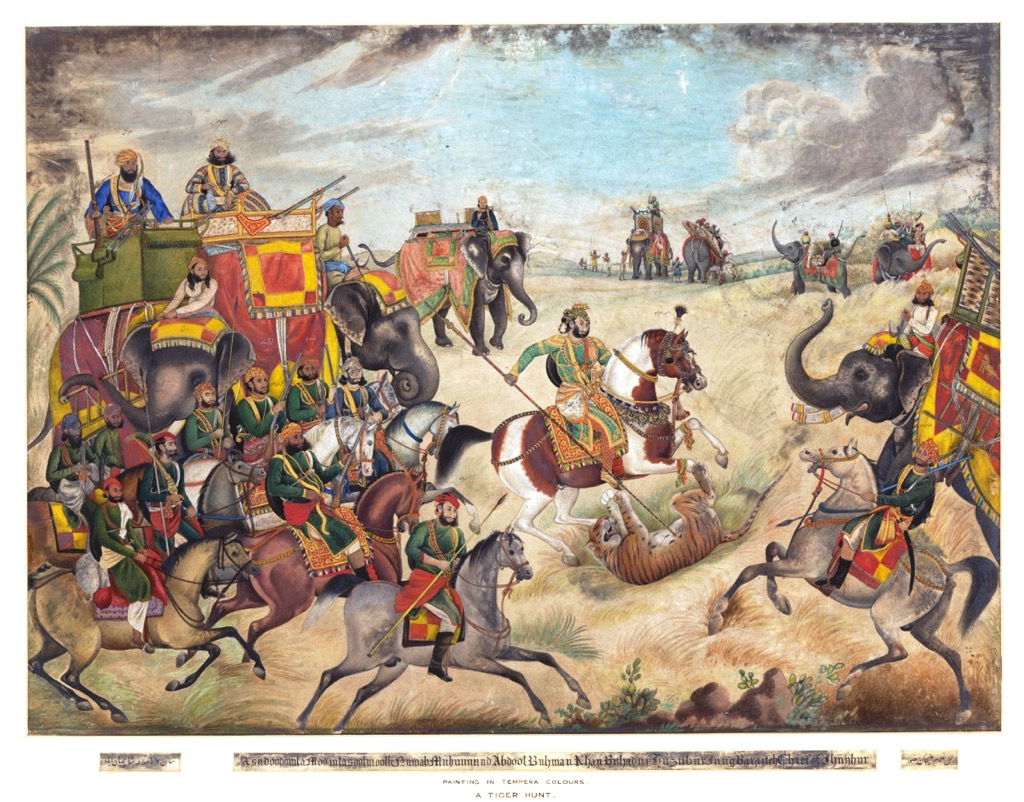

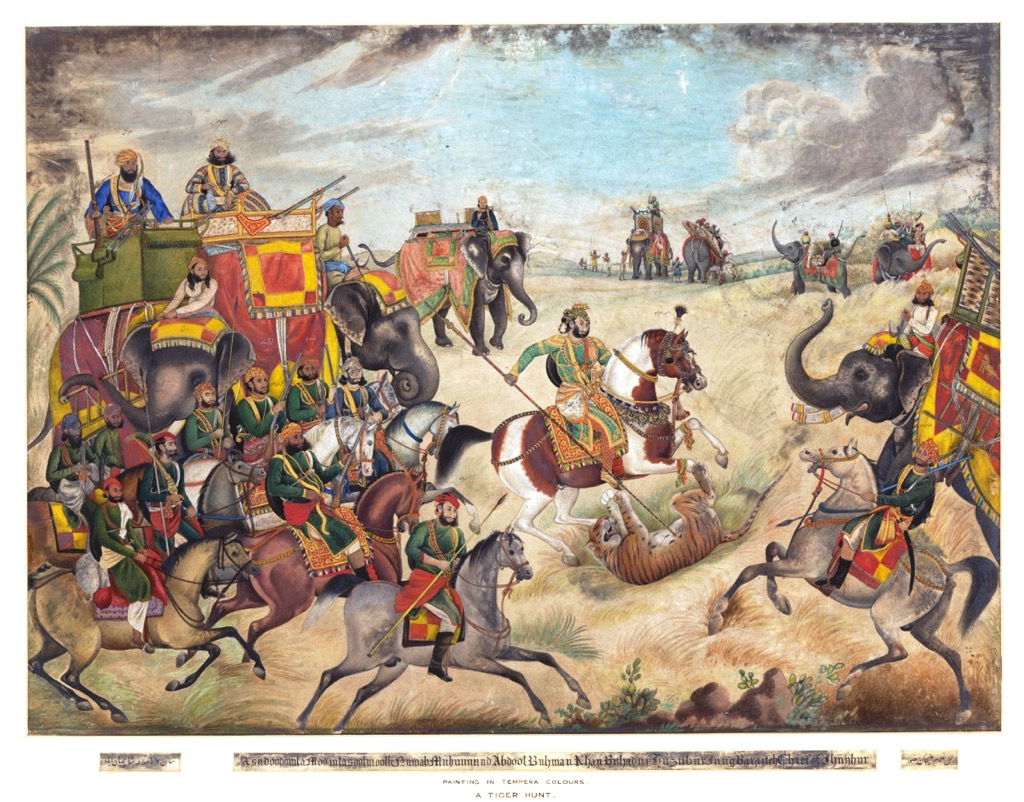

The Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE) and the later Guptas extended their power into Haryana, as did the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals after 1200 CE. Being a vast open plain directly connecting Delhi to northern India, Haryana was no stranger to some of the bloodiest military confrontations in India’s history, such as the Third Battle of Panipat (1761) between the local Marathas and Muslim invader Ahmad Shah Abdali.

In 1857, the British incorporated Haryana and Punjab Province, but linguistic differences and frequent revolts later led independent India to claim Haryana as a separate state in 1966.

Depending on the setting, the Haryanvi people speak Hindi or English, despite regional dialects like Haryanvi or minority languages like Punjabi. Despite its linguistic homogeneity, its population still identifies strongly with historical castes, often heavily intertwined with occupation and ethnicity. For example, its large agrarian communities identify as Jats, while Brahmins tend to occupy religious occupations, administration, and education.

With a population of 30 million, Haryana has nearly doubled in size in the past decade and is India's third fastest growing province. Despite its proximity to the blossoming NCR, roughly 65% of its people still live in relatively poor rural settings, and even in urban areas, many still face poverty, including migrant laborers from Bengal, Bihar, and other poorer states. In fact, Nuh district–home to Haryana’s Muslim minority, just outside of Delhi, is not only the poorest in Haryana but also among the top ten poorest in the country.

In modern Indian history, apart from its industrial and IT prowess surrounding the southeastern NCR, Haryana is primarily known for being an active center of the so-called Green Revolution that led to hybridized seed varieties and increased grain production.

With ecotourism on the rise, the state hosts a number of protected areas, including two national parks, abundant wildlife sanctuaries, and eco-sensitive zones designed to protect remaining biodiversity.

For those seeking deep greenery, look no further than Kalesar National Park & Wildlife Sanctuary in Yamunanagar, where leopards, elephants, sambar, and wild boar roam the remaining Shivalik Sal forests. Formally, Kalesar forms a part of the cross-state Shivalik Elephant Reserve. Slightly to the northwest lies Bir Shikargah Wildlife Sanctuary in Panchkula, best accessible from Pinjore. A former hunting ground of the royal family, Bir Shikargah still features abundant deer, wild boar, and peafowl.

For those in search of wetlands and migratory bird watching, a quick drive out of the NCR will do. Despite rampant pollution and habitat fragmentation, there still exists an ecological corridor around the Sahibi River from the northeastern Aravalli Hills in Rajasthan to the Yamuna in Delhi. This is home to numerous protected wetlands and fragmented forests, including Khaparwas Wildlife Sanctuary, Bhindawas Wildlife Sanctuary (designated as an official Ramsar site), and Sultanpur National Park.

In winter, migratory birds like Siberian cranes, flamingos, and pelicans stop here to feed and rest on their way south. This region offers a perfect weekend picnic getaway with child-friendly facilities and watchtowers. If venturing further north on the way to the Shivalik Hills, Chhilchhila Wildlife Sanctuary in Kurukshetra is likewise a must-visit for those excited to spot birds like the sarus crane.

In the dry western portions of Haryana, the small (2 km²) Nahar Wildlife Sanctuary in Rewari exemplifies the semi-arid Aravalli ecosystem, boasting nilgai, jackal, and various bird species. In the northwesternmost corner of the state, on the border to Punjab, the lesser-known Abubshahar Wildlife Sanctuary, at a staggering 115 km², is another potential spot to check out, particularly for local monkeys. The sanctuary is largely community-managed and less advertised, despite its size.

When it comes to serious hiking, Haryana’s northeastern Panchkula and Yamunanagar districts are your best bet. Around a 4-5 hour drive from Delhi, these districts hug the Himalayan foreland. State-capital Chandigarh is a perfect base to explore nearby Morni Hills, or to take a legendary ride on the UNESCO world heritage Kalka Shimla Railway that runs through Himachal Pradesh’s southern hill country.

To get acclimated, take a morning trail run through Sukhna Wildlife Sanctuary, where the urban heat cools off in the presence of striking birds, boars, and deer, just north of Chandigarh.

For those ready to trek, the Morni Hills are just an hour’s drive away. At an elevation of 1200 meters (3600 feet), Morni’s waxy pines adorn the hazy hilltops, while loamy clay paths connect villages nestled within neem, oak, and pipal woods. In spring, entire hillsides transform color while quails, sand grouse, and doves rush from above.

For the ardent hiker, a trek up Karoh Peak, Haryana’s officially highest point on the border to Himachal Pradesh, is an absolute must. Ask locals how to get there, as the hike is not readily advertised. The best bet is to sleep at Skylark Forest Rest House, roughly a 20 km journey from the more famous Morni Fort. Bring plenty of water and good shoes. From there, a 2-hour hike up the 1467-meter summit rewards with views.

If in Morni Village, however, hikers will most likely be offered tours to Morni Fort and the Tikkar Tal lakes, featuring a 12th-century temple adorned with a Hindu trinity. Like Karoh Peak, a trek to the banks of the river Ghaggar offers adventurers a more off-the-beaten-track itinerary.

At first sight, Haryana may be a relatively arid and forestless state. Kalesar National Park will surprise with its well-preserved Sal forests, where leopards, elephants, and other mammals abide. Numerous safari services exist, as do local ex-colonial bungalows with excellent views of the Yamuna River and surrounding birdlife.

Unlike Morni Hills or other areas in Haryana, Kalesar has less marked trails, more dense green canopies, and an authentic “forest” feel. The park is only open in the winter months, and its elevation of 1000 meters brings cooler temperatures, so make sure to dress accordingly. Also, be sure to check out the thriving culture of medicinal plants at nearby Ch. Devi Lal Herbal Nature Park, as well as the local tradition of harvesting sindoor pods from the sindoor tree, used to make vermilion facial paint for married Hindu women.

While Haryana’s portion of the Aravalli Range, curving around the eastern border of the Thar Desert all the way to Delhi, may not entice the forest or mountain enthusiast, its iconographic treasures make up for it.

Haryana’s southwest can be described as a mystical, semi-arid entryway into the world-famous landscapes of Rajasthan. Abandoned ancient copper mines, sulfur springs, fragrant essential oil shrubs, and countless holy sites abound alongside prehistoric volcanoes, crumbling hills dotted with pilgrim stairways, and age-old ashrams. For those based in or around Delhi NCR, Aravalli Biodiversity Park, Gurugram, provides an excellent place for a morning hike along its easily accessible marked trails, native flora, and a variety of bird species.

For those seeking a more remote experience, Dhosi Hill, accessed from the Mahendragarh district, forms an ancient volcanic mound reaching 740 meters. Associated with sages and Ayurvedic cures, the trek to the hilltop includes sulfur-rich water tanks, restored temples dating back to Vedic epics, and a scenic view of the endless patchwork of rice fields and bordering trees below. During monsoon season, the rains overwhelm the reservoirs at the top, feeding several waterfalls that cascade down the volcanic rock walls.

Further up north, on the western border of Rajasthan, religious pilgrims and hikers alike may venture to the Tosham Hills, rich in copper ore, Harappan ruins, and 2500-year-old epigraphs etched into rock walls. Tosham Hill, known for its cascades and its ancient monastery, is not much of a hike (200 meters), but has much history to offer. Unlike Morni Hills or Kalesar, these hills lie amid relatively unassuming agricultural villages unbeknownst to tourism. Hiring a knowledgeable guide is recommended for those who lack a PhD in ancient Indian archeology!

Apart from its numerous outdoor activities and impressive cities, Haryana's culture is steeped in agrarian folk traditions and legacies, kept alive through music, dance, and artisanship.

While Haryana may not be known for a particularly pronounced cuisine, some local twists on khichri (rice and lentils), multicolored dal, dried pakora fritters, and roti (classic flatbread cooked in tandoori clay ovens) are must-try snacks after a big hike or near a popular picnic spot. Vendors are omnipresent. Like their Punjabi neighbors, Haryanvis love their lassi. On a hot summer day, particularly from April to May, where peak temperatures meet peak mango season, make sure to ask for a refreshing mango lassi, often spiced with cardamom, mint, or saffron.

Besides food, the spirit of Haryana is deeply rooted in its agrarian folk celebrations. For the international traveler, the abundance of festivals can be overwhelming. A good place to start is Surajkund International Craft Mela in Faridabad: Haryana’s most famous cultural event featuring artisans, dancers, and cuisines from across India and other countries. If near Morni Hills, make sure to attend the Pinjore Heritage Festival at the Pinjore Gardens.

If you thought that was all, it’s just the beginning! There’s also the Teej Festival, celebrated by henna-painted women with song and swing dances, not to mention Baisakhi & Holi marked by entire villages erupting in dance and music.

Learning to dance traditional dances like Dhamal, Phag, Loor, or Khoria could be worth a try. Or try to sing along as folk theatres feature Ragini, a popular local singing style. While many of these traditions are seasonal, often heavily intertwined with the harvest periods and springtime, no matter what time you visit Haryana, you will surely find a buzzing temple, roaring theatre, or exciting conundrum of dance and song.

Chandigarh, the shared capital with neighboring Punjab, offers visitors a clean and ecological feel. Its center was designed by architect Le Corbusier, as part of a government plan to establish an impeccable, well-organized state capital. Similarly, Yamunanagar—situated just outside the Shivalik hills and a stone’s throw away from Kalesar National Park—is an excellent base for nearby nature exploration. The city itself is primarily a wood processing hub.

Due to central planning and geographic factors, most of Haryana’s other cities specialize in specific economic activities. Examples include northwestern Sirsa, where daily life revolves around cotton and grain production, serving India’s many grain distribution and weaving districts. Karnal, known as the “rice bowl,” is the center for rice production and seed research. Near the NCR, Gurugram and Faridabad are some of India’s fastest-growing IT hubs and major manufacturing districts, respectively.

Explore Haryana with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.