Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Diyarbakir is one of 81 provinces in Turkey, located in the larger region of Southeastern Anatolia, near the border with Syria. The province surrounds the city of Diyarbakir, its largest population center, which is flanked by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Diyarbakir is the northernmost extent of historical Mesopotamia. The province’s south is primarily covered in a low plain, which sweeps up into prominent peaks of the Eastern Taurus Mountains and the Armenian Highlands to the north. There are 242 named peaks in Diyarbakir, the highest of which is Andok Tepesi (Mount Andok) (2,813 m / 9,229 ft) on the border of Muş Province. The most prominent peak in Diyarbakir is Karacadağ (1,961 m / 6,434 ft).

Diyarbakir Province sits on the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent, south of the Armenian Highlands, and west of the Taurus Mountains. It is part of Turkish Kurdistan and the larger Turkish region of Southeastern Anatolia. The province surrounds the city of Diyarbakir, which includes about two-thirds of the total population.

The city sits between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in the northern extent of what was historically Mesopotamia (literally, “the land between rivers”). Mesopotamia is the birthplace of modern human civilization. The area surrounding Diyarbakir was one of the first on Earth to be converted to agricultural land.

The Tigris and Euphrates both flow out of the Armenian Highlands, north of Diyarbakir. They flow southeast from their headwaters, almost parallel, through Turkish Kurdistan, Syria, and Iraq to the Persian Gulf.

Mesopotamia once occupied a broader desert plain, the Fertile Crescent. At first, the area seems like an inhospitable desert, and it now has one of Earth’s hottest climates. Ten thousand years ago, a cooler, wetter climate dominated the region. Ultimately, the climate gradually became hotter and drier, and the arable land became more saline, contributing to the dissolution and evolution of civilization here. Nevertheless, once upon a time, the area’s ecology and climate (mainly the abundance of fresh water from the Armenian Highlands) produced the perfect conditions for humanity to develop early farming techniques and domesticate livestock.

Moving north, the Fertile Crescent sweeps up into mountain peaks. The Taurus Mountains and Armenian Highlands join near Diyarbakir, though there is no clear geological boundary between them. Generally, the Armenian Highlands are more conical and feature prominent volcanoes like Mount Ararat (5,165 m / 16,946 ft), whereas the Taurus are more of a typical chain of peaks connected by ridges. The largest mountains in the region are near the town of Kulp, closer to Muş Province. But the most prominent peak is Karacadağ, a giant shield volcano that rises abruptly from the plain west of Diyarbakir.

The Armenian Highlands are the largest plateau in West Asia, stretching from the Caspian Sea south of the Caucasus Mountains to the Black Sea and well into Anatolia.

The Highlands comprise a chain of volcanoes. The rock in the area is primarily igneous; exposed tuff, basalt, and rhyolite leftover from volcanic eruptions are all common.

Basalt deposits from fast-flowing lava on the surface often form lava tubes, cylindrical caves that run just under the surface. Tuff, made from volcanic ash, is commonly seen in rocky buttresses. Rhyolite, rich in silicates, results when lava flowing from vents cools quickly on the surface.

The Highlands are very geologically active, and volcanism has produced major shield volcanoes like the aforementioned Karacadaǧ and cones like Mt. Ararat and Mt. Nemrut (2,205 m / 7,234 ft). Tectonic movement has also created three large lakes around Diyarbakir: Sevan, Van, and Urmia. These water sources feed the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, which provide water to around 60 million people. The abundance of water in the area has caused extensive erosion, shaping the range into winding canyons, an uncommon sight in volcanic mountain ranges.

The Fertile Crescent is a desert steppe. Life in harsh desert climates favors r-selected plant species, like annual grasses. These species produce large amounts of seeds, which humans typically use for food; thus, r-selected species are more common as crops. The ample water from the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in combination with historically cooler, wetter climatic conditions, created the perfect conditions to give rise to agriculture.

The lowlands around Diyarbakir are also part of the corridor between Africa and West Asia, which favors migratory mammals (like cattle) and birds. This almost certainly aided in the beginning of livestock farming - humans first domesticated wild aurochs into conventional cattle near Mesopotamia around 10,500 years ago.

Humans began terraforming the Fertile Crescent 12,000 years ago, and since that time, the area hasn’t been in its natural ecological climax community. Because of the long history of agriculture in Diyarbakir, it makes more sense to refer to how the area’s ecology was than how it is.

Using similar ecosystems as models, pre-agricultural Mesopotamia was most likely a grassland populated by large grazing mammals like the pre-domestication aurochs, donkey (onager), and goat. Evidence suggests that the horse was not native to Mesopotamia before being domesticated. In fact, one of the first pack animals domesticated in Mesopotamia was the kunga, a donkey-onager hybrid. Long-distance soaring birds like eagles and vultures typically thrive in these ecosystems, as they can traverse huge distances in search of carrion and prey.

Beyond the low plains, the Armenian Highlands have a huge elevation gradient, contributing to more diverse ecosystems. Montane forests persist in the lower to middle mountainous elevations, particularly in canyons and places where snowmelt collects. The higher elevations of the Taurus and Armenian Highlands are mostly barren and covered in grasses, shrubs, rock, and, during winter, abundant snow (the highest elevations of Ararat are also extensively glaciated). Generally, the mountains support more grazing ungulates and mammal predators like the Anatolian leopard, lynx, gray wolf, jackal, and even striped hyenas.

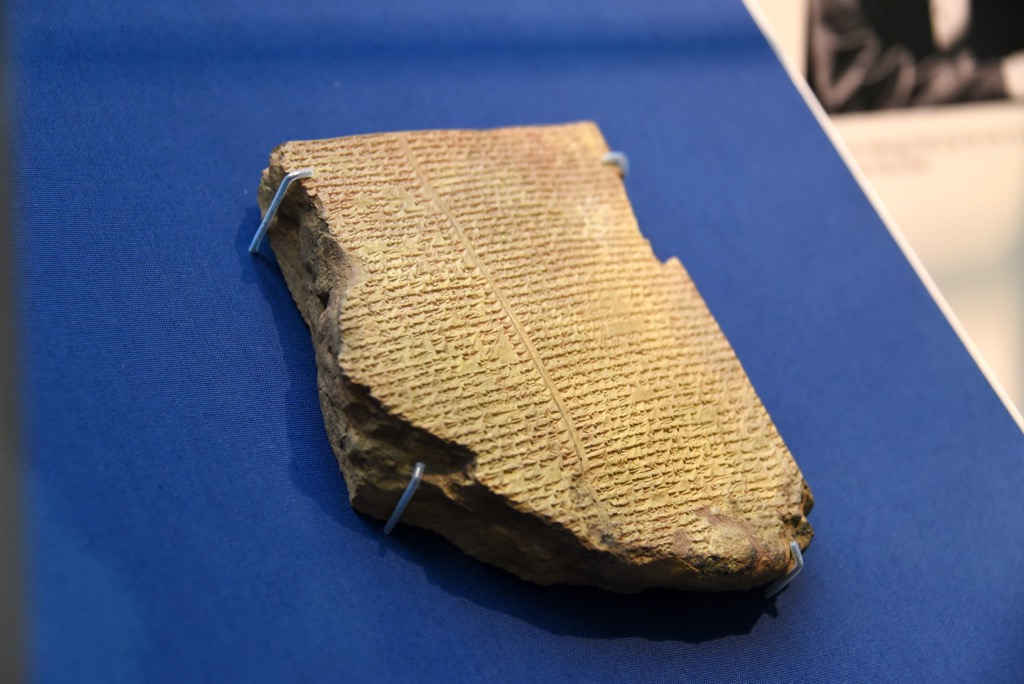

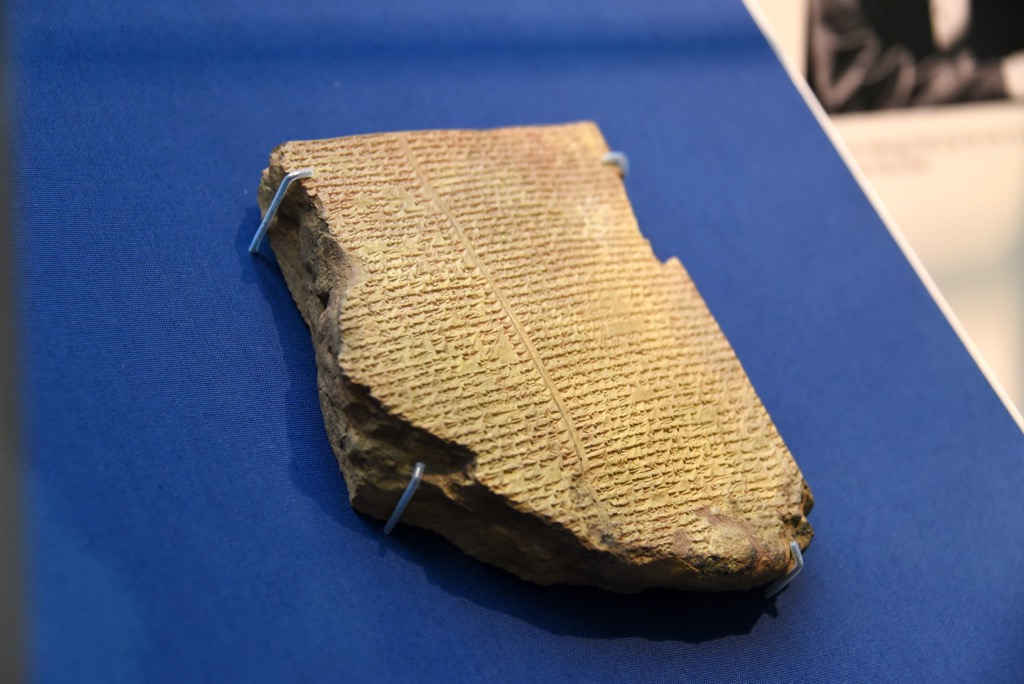

The main story of Diyarbakir is its place in human history as a part of Mesopotamia. This place was the site of the world’s first modern civilization, circa 10,000 BCE. It is where we see the first evidence of agriculture, the invention of the wheel, the creation of writing (Sumerian cuneiform), mathematics, astronomy, the first use of gold as currency (the Mesopotamian shekel), organized industry and religion (Zoroastrianism), the construction of political and religious edifices, and many other aspects of modern civilization.

From 10,000 BCE to about 3,000 BCE, a dozen or so different cultures inhabited Mesopotamia, each of which existed from hundreds of years to well over a millennium. Sumer was the first and most important of these, but was restricted to Southern Mesopotamia in what is now Iraq.

The next significant change came around 3,000 BCE with the start of the Bronze Age. Metallurgy was one of the most important inventions in human history. It dramatically increased not only the capacity to build and farm, but also to make weapons and wage war. By the start of the Bronze Age, Sumer had shrunk, and the Assyrians and Akkadians controlled most of Mesopotamia.

The Bronze Age saw the establishment of new city-states like Babylon, many of which lasted for over 1,000 years. Around the 6th or 7th century, Zarathustra Spitama founded Zoroastrianism, one of, if not the oldest organized religion on Earth. This period of history is defined by the rise of greater and greater empires, each attempting to conquer all of civilization. First were the Persians, who caused the collapse of Babylon in 539 BCE. Then Alexander the Great, the Parthians, and the Romans. Finally, in the 7th century CE, the Muslims swept over the area, more or less ending the widespread influence of Zoroastrianism.

From that point on, Mesopotamia has been culturally and religiously Muslim. Turkey became the seat of the Ottoman Empire, which lasted 600 years and swept from Eastern Europe to the Persian Gulf and well into Africa. The Ottomans were ousted in the 1900s when they lost a series of revolts, including the Young Turk Revolution and the Arab Revolt. Since then, Diyarbakir has been part of the Republic of Turkey.

The Armenian Highlands are full of worthy hiking objectives, but finding information on routes and conditions can be sketchy. These are some of the best hikes in Diyarbakir, and here is some information to get you on the trail. Like in other remote places, the best information exists not on the internet, but through the eyes of the locals. Speaking to locals and seeking out informal trails will be your best bet. Many trails are visible on Google Earth, which is often a great resource for finding routes in remote places. Fortunately, the mountains here are ripe for exploration, as there are relatively few hazards compared to larger ranges.

Karacadaǧ (1961 m / 6434 ft) is the most prominent peak in Diyarbakir Province and has an easily accessible trailhead by road. The trail starts in the town of Karacadaǧ, southwest of Diyarbakir. From there, the trail heads west onto a north-south ridge, where it meets up with another trail that runs over the peak’s spine. The total trek is about 32 km (20 mi) round trip, which would be a good option for a long day or an overnight backpack. From the town of Karacadaǧ, the route climbs 926 m (3,038 ft) to the summit.

The town of Kulp sits at the foothills of the mountains and is a solid entry point into the highlands. Continuing up the Kulp-Muş Road, many trailheads lead up into the mountains. Four-wheel drive may be necessary off the main road to get to some of the trails.

One of the approaches to the Andok Tepesi summit follows this road up, then turns east up a canyon at Alaca. Past Alcala, the road is high clearance only and climbs from 1,117 m (3,666 ft) to 1,615 m (5,300 ft). The trail sidehills along the canyon before shooting up to the northwest ridge of Andok Tepesi. The ridge turns south, gaining elevation to 2,813 m (9,229 ft) at the summit. Andok Tepesi is one of the most technical peaks in Diyarbakir Province; the peak holds snow much of the year, and crampons, ice axes, or trekking poles may be necessary to make the summit.

You could also hike Kulp Daǧi (1,842 m / 6,043 ft) from the town of Yalak, west of the Kulp-Muş Road. A loop trail heads west up a canyon to a ridge which curves back south, and then east. From here, you can turn south to the Kulp Daǧi summit or continue east to another high point, which tops out at 1,961 m (6,043 ft).

Diyarbakir is the largest population center in Diyarbakir Province, which is otherwise very sparsely populated. The province’s total population is 1.8 million, of which 1.13 million live in Diyarbakir city. The city itself is full of ancient ruins like Diyarbakir Fortress, which is surprisingly intact. There are several historical stone bridges over the Tigris, as well as the city’s old stone wall, which you can walk over. The Great Mosque of Diyarbakir is the oldest in Anatolia, built in the 11th century by the Seljuk Turks. The city also has an old market, which has been converted into a cafe stroll. You can get to Diyarbakir by plane, train, or bus. The airport has regular flights from Istanbul and Ankara, and rail lines run regularly to Batman.

Explore Diyarbakır with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.