The Écrins Most Exalted Refuge and Ski Descent

By Sergei Poljak

Introduction

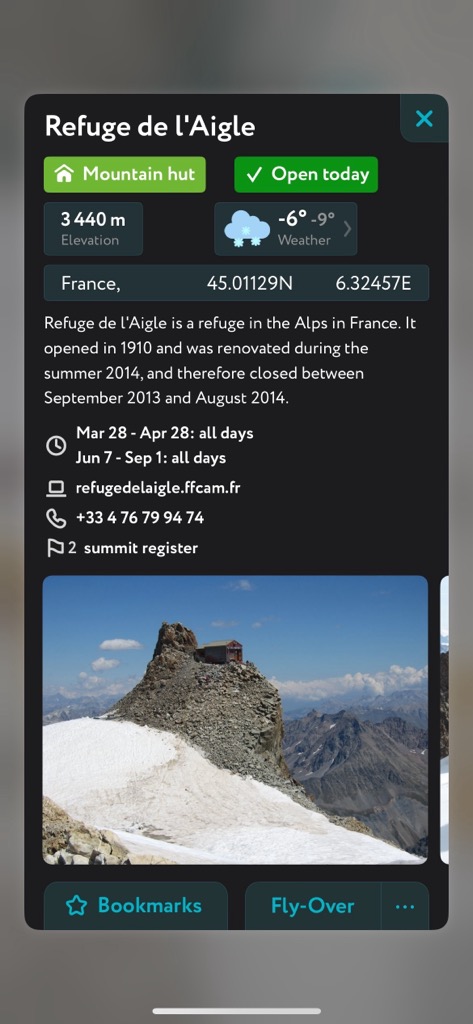

Since she was a wide-eyed, 18-year-old first-timer in La Grave, France, my girlfriend had harbored a dream to stay at the Refuge d’Aigle. Known as one of the most—if not the most—beautiful refuges in the Alps, the Aigle also has a reputation for always remaining just out of reach, especially in the winter. I hadn’t thought too much about the Aigle myself; my first two seasons in La Grave were historically dry, and I don’t even think it opened in my first year.

But as wet snow began to plaster the glaciers in October and November, it was clear that this year would be different. Thus, we hashed a loose promise to spend the night here sometime during winter. The saga of the Aigle had begun.

The Eagle Refuge, to indulge you with its English translation, sits at an altitude of 3,450 m (11,319 ft) on a ridge separating the L’Homme and Tabuchet Glaciers. The hut is surrounded by a who’s who round table of the Écrins’ giants; the Pic Gaspard, Meije Orientale, Doigt de Dieu, and Grand Pic de La Meije stand menacing and frozen in the heavens.

The Aigle is mainly a summer residence for climbers on various missions, like the legendary La Meije and Meije Orientale (climbers leave from the Refuge du Promontoire to summit La Meije but usually come to the Aigle on the way down). However, it opens up for a few short weeks in April (this year was just 18 days) as a haven for skiers looking to undertake some of the Alps’ most epic descents. In addition to the physical challenge of reaching the hut, which is a 1900 m / 6,234 ft ascent from the hamlet of Villar d’Arêne, you have the added challenge of finding the right conditions.

We hoped to ascend the Tabuchet Glacier, which hangs in stupendous fashion above the legendary ski town of La Grave. That’s because we didn’t want to do the Serret du Savon, the more common and less physically demanding route to the Aigle. The last two winters have been warm and dry, only to be followed by even warmer and drier summers. As the Glacier de la Meije made its inscrutable but intractable advance down the mountain, no new snow fell to replace the ice, exposing slick rock at the base of the couloir. Whereas the Serret had become a piece of mixed climbing with a history of rockfall, the Tabuchet remained as a long but relatively non-technical option…and hopefully one with our names on it.

The Winter Unfolds

The Écrins' winter during 2023-24 encapsulated the new era of climate change. On the one hand, the massif bore the brunt of a series of early-season storms that delivered eye-popping snow totals to the higher elevations. The central Écrins weather station at the base of the Glacier de Bonnepierre at 2900 m had already accumulated a base depth of 3 m (10 ft) by mid-December, breaking a record. As ski season approached, you could feel the relief and anticipation settle over La Grave.

Meanwhile, Europe continued to be plagued by warm temperatures. While the snowpack up high was extraordinary, the lower slopes struggled to retain snow for much of the winter. The mid-December storm cycle that brought a record early snow depth to the Écrins was followed by a warm spell, promptly souring conditions for La Grave’s opening day. Similarly, the first half of January featured deep, blower powder days followed by sudden, unseasonable warming, which turned snow conditions to ice.

And so the trend continued throughout the season. We would have epic snowfalls and powder days followed by warmth and rotten snow. The lack of consistency also made finding conditions for big ski tours difficult. Catching the hours-long weather window after a storm was like bow-hunting gazelle at 1,000 meters. Unfortunately for us, the pattern continued right up into April.

On the other hand, a new opportunity had begun to arise. For the first time since 2017-2018, the Glacier de l’Homme was in good condition for skiing. Whereas the past two years of drought and melting had reduced the proud L’Homme to a crumbling, tumbling pile of seracs during the summers, the glacier was reborn in 2024. Each storm cycle further filled in the crevasses, and by March, the L’Homme was looking less like the Khumbu Ice Fall and more like a typical, healthy glacier. Like, you know, when the glaciers in the Alps used to have snow on them?

It was also becoming clear that the Glacier de L’Homme was part of a mythical tier of ski lines. Pelle Lang, the infamous La Grave originator, told us simply that it was “in his top ten descents.” Personally, that’s all I needed to hear. When something is in Pelle’s top ten, it should probably be in yours, too.

Choosing a Date

Due to a maintenance issue, the Aigle didn’t open on March 28 as intended and instead had to postpone until April 10th, further shortening our small window for entry. It was for the best anyway, as the Télépherique in La Grave was closed for a brutal eight consecutive days during the final days of March and the beginning of April. I doubt even a single person would have made it to the Aigle.

Nevertheless, we knew the conditions were in after having done a number of other ski tours in the Écrins and spoken to local guides. Apparently, crevasses on the main route were of relatively little concern, having been covered by four or five meters of consolidated snow.

We initially chose Thursday, April 11th, as our date. Consistent with the season's trend, it was another extraordinarily brief window. After yet another fall of fresh snow, conditions were good, but rapid warming was fast approaching. Temperatures were forecast to hit 7℃ at altitude on Friday, the day of our descent. With the added pressures of an unstable snowpack and a persistent wind at altitude, we opted out.

I was glad we did, though we later discovered that at least a dozen parties did the L’Homme that weekend, despite temperatures hitting 11℃ at 3100 meters on Saturday and Sunday; I believe all of them approached from the Savon and not the Tabuchet.

Instead, we swam and biked in summer temperatures down in the Savoie. Records across Europe were shattered; Innsbruck, Austria, broke its monthly temperature record on just the 13th of April, far earlier in the month than the previous records.

Upon our return, the weather pattern shifted, and temperatures dropped significantly. We set our date for Friday, April 19th. There was weather coming in, but with a morning window, and Saturday looked suitable for the descent.

The Ascent

Friday was cold, and I led a campaign to use the frigid temperatures as an excuse to start a little less early. Bushwacking through forests and managing scree fields in the dark, all under the watchful eyes of the wolves, was too much for my psyche to handle. So we aimed to start at 6 a.m.; not quite a proper alpine start, more what is colloquially known as “the ass crack of dawn.” Still, with the mountains and the impending alarm haunting our dreams, neither of us slept particularly well.

In the morning, we arose, ate heartily, and clacked out the door in our ski boots at around 6:15 a.m. Not too bad for a couple of night owls.

As is the story with the last few years, it was a hike for the first three hundred meters or so. We followed the GR-50 from Villar d’Arêne up to its crest between La Grave and Villar, then turned left into the larch trees. When we finally emerged from the forest, crossed the scree, and gained the first tongue of snow, it was obvious that this would remain a hike. The snow, having been reduced to mashed potatoes by the heat of the preceding weekend, had now frozen to the consistency of a glacier.

And so it went—no less than 1300 meters (4,265 ft) of booting up with crampons. It was too steep to walk but not steep enough for toe points, so we sidestepped most of this; now I understand why they call it the French Technique.

The route crosses a slight ridge and continues straight up to the Tabuchet. Once you cross the ridge, you stick close to the rocks on your left and ascend the gully feature on the glacier’s flank. It’s remarkably straightforward and direct, considering how much elevation you gain. It would be an enjoyable skin, too; precisely the right pitch for steep, rhythmic kick turns. Unfortunately for us, that was not to be the case. It was simultaneously annoying and tense, booting up steep, icy terrain for so long.

Finally, there began to be a thin layer of powdery snow on the crust. Somewhere around the start of the glacier (~2,800 m), we tried to transition over to skins, but the new snow was simply too powdery and the crust too icy. This precipitated several back-and-forth transitions, trying to skin but being unable, even with ski crampons. Anna also had a massive skin failure where one of her skins completely imploded with the other close behind. Not even ski straps would hold; it took a mountain of climbing tape to nurse them to the top.

When we finally reached a skin-able snow surface well above the start of the glacier, it became clear that our weather window was closing even sooner than predicted. The dark clouds that had been forming all morning began to descend. Winds picked up and swirled little tornados of spindrift around. It became hard to hear anything besides the roar of moving air.

By the time we reached about 3,200 meters, it had begun to snow, and visibility had long since vanished. Now, we were in a world of phantoms. Large crevasse systems appeared on the Tabuchet to our right; as I said, always stay against the rocks. Ultimately, there was little chance of getting lost with the PeakVisor App. You’ve gotta love GPS technology in this day and age.

After 7.5 hours and 1900 meters of booting, skin failures, lost time, incessant wind, and accumulating rime ice, frustrations were running high when we reached the refuge. Well, by the time PeakVisor told us we’d reached the refuge because you couldn’t see it until standing right next to it.

The Refuge d’Aigle

The Aigle stands perched atop a rock spire between the L’Homme and Tabuchet Glaciers. When we finally caught sight of it the next day, as the clouds cleared, I thought, “It really does look like an eagle in its nest, surveying its kingdom.”

The Aigle had been booked out when we checked the night before, but when we walked inside, it was deserted. The guardians greeted us and mentioned that we would be solo. Everybody else had bailed.

The heating wasn’t working; the solar panel had apparently not received enough sunlight to operate the thermostat. The temperature outside hovered between -10 and -15℃. As for the inside, it sustained a balmy 2 or 3℃; our water bottles didn’t freeze, but everything else did. Your breath was especially visible in the confines of the refuge, and a semi-permanent steam cloud hung in front of our faces for the next 20 hours.

For Anna and I, it was straight to bed with as many comforters as we could pile on top of us. Even then, it took hours to eradicate the chill that had settled into our bones. Missions to the bathroom were particularly heinous, having to go outdoors, brave the wind and snow, and drop trou in the cold stall. In some ways, we had finally escaped the wind. But we never escaped the sound. In the refuge, it sounded like the weather gods shaking a giant blanket directly above our heads. The vent violent continued unceasingly until we left, and even when we finally returned to La Grave, we could see the snow still swirling around on the Tabuchet.

Dinner was served around six p.m. We were ravenous, and the meal was delicious. There’s nothing like a pasta bake at 3,450 meters. The guardians offered pleasant conversation and beta for the next day’s descent. We spoke of the future of the Aigle. Someday, maybe, the glaciers and permafrost would melt away enough for the refuge to collapse. “But don’t worry,” the male guardian said, “the water in our bottles is still level.”

In the end, Anna and I had to call it an evening. Our feet were simply too cold to continue sitting at the table. After constructing a fortress of blankets around our persons and one final bathroom trip to avoid getting up at night, we allowed the wind’s tireless din to lull us into sleep.

Sleep for Anna was fitful. It turns out, trying to sleep at 3,450 m can be pretty difficult. She woke in the middle of the night, literally gasping for air. I recall the same thing happening to me in the first days after moving to Colorado many years ago. As for myself, I believe there were two bathroom trips through the raging snow and wind. Just between you and me, I may not have made it through the thigh-deep snow drift to the loo and instead contributed a bit of ice to the L’Homme. But otherwise, I slept surprisingly well. Nothing beats a solo refuge without the snores of fellow cordistes.

The Glacier de L’Homme

Morning arrived with a call to the breakfast table at 7 a.m. and the realization that about 50 cm of snow blocked the walkway to the bathroom. We ate bread, butter, and jam, tried to warm ourselves with coffee, and shoveled (well, to give credit where it’s due, Anna shoveled).

Around 8:30 a.m., the skies had cleared, offering views of a majestic amphitheater of skyscraping peaks. It was the first time I’d been able to see the mountains, or anything for that matter, since we’d arrived. The Glacier de L’Homme descended like an elevator shaft, peppered with sapphire blue seracs. I’ve gazed up at La Meije many thousands of times, but this felt like the very first time. I felt like a little La Meije virgin.

We spent some time gazing around, but then it started to dawn on us that we would have to find a route down from this beast of a mountain. The wind was absolutely howling, and the glacier would periodically disappear from view amidst the spindrift. I realized that the Eagle hut didn’t just survey its kingdom but actively sought to devour prey.

We tossed on the skins (or taped them, in Anna’s case) and bid farewell to our frigid sanctuary. Our new sanctuary - the great outdoors - was even more frigid. The wind was nearly blowing us over. We skinned a bit further up the ridge to where the Tabuchet and L’Homme meet. We had peered at PeakVisor, spoke with the guardians, and scouted this very line right from the hut a few minutes ago. However, the wind was blowing so hard and the convex slope dropped into the abyss. I couldn’t see much of anything through the spindrift, yet it was like skiing on ice; it felt like all the snow was in the air. The only shapes coming through were jagged seracs. Ok, I'm pretty sure we have to ski between this one and that one, and then we’re on the glacier…

Alas, it seemed too risky. Plus, our faces and feet were bordering on frostbite. It had been half an hour since we’d left the hut, and the wind was relentless. We turned back to the refuge.

Back at our slightly less frigid sanctuary, we attempted to defrost our feet as we sat, wondering if we’d ever get off the mountain. The Tabuchet would be even windier with horrible snow conditions, so we didn’t want to retreat the way we came. The guardians suggested going into the entrance right below the hut. After an hour or so, feeling returned to our feet and faces, and to our surprise, it even seemed like the wind had died down a bit, although this may have been an illusion. We geared up and walked down.

We busted out our ice axes, and Anna kicked off a small cornice that had built up with the storm. Then we scooted in. It was steep but not nearly as steep as it looked from above. The snow was horrible, but the wind became less extreme as soon as we began to ski down into the L’Homme.

Amidst the diminished wind, we looked around to observe our newfound environment. Lots of seracs but plenty of passages. It was wild to be up here, a place that I’d looked at literally every time I’d ever driven home on the Col du Lautaret. It looks savage from the road, and it’s savage once you’re in it.

Everything was white, and there were no tracks to follow. We headed down the path of least resistance, which was…straight ahead and down. The fresh snow, non-existent and wind scoured on the glacier’s flanks, had collected here into a thick, dense windslab. A bit of an avalanche hazard, but it drastically improved the skiing. It seems this fresh windslab had covered up a crevasse, which Anna promptly opened as she skied over. Luckily, it’s harder to fall in when you’re skiing down…

I skied soft and light down to the next convexity, where we crossed over to the skiers’ right under some teetering seracs and then back to the skiers’ left. The guardians had assured us that the worst of these seracs had just tumbled down in the last couple of days. Indeed, they had, and the next 500 meters was a mess of ice blocks, some of which were visible and some hidden under the new snow. We won’t go into the gritty details, but this part of the route was not that obvious, and there were definitely some wrong turns and side-stepping around.

The next part of the route involved exiting the L’Homme into a series of very filled-in chutes, which led to the toe of the Lautaret Glacier and eventually out onto the remnant Glacier d’Armande. In good snow conditions (corn snow, at this time of year), this is the place to open it up and have some Type A fun on this route. Alas, our snow conditions left something to be desired; it was too cold and the snow had only slightly transformed.

We then skied ice, pebbles, and twigs down to the upper reaches of the Romanche River, which we crossed on a ladder bridge. Some chamois scattered up the hillside before us. After putting our skis on our backs, we took a last glance at the mountain and our line. Then, we headed back to Pied du Col, where I’d left our car.

Final Thoughts

There you have it, folks. That’s the saga of the Aigle. It was Type B fun for sure; we’ll look back at it with smiling eyes, but it was a bit stressful in the moment. The refuge and its two main ski descents, the L’Homme and the Tabuchet, are some of the best in the Alps. We didn’t catch it in powder or spring corn, but we at least saw it filled in, which is becoming increasingly rare. Maybe you’ll have better luck.

To leave you with a final bit of inspiration from the late, great philosopher John Dewey:

One evening, several months before his 90th birthday, John Dewey was discussing cultural trends with some dinner guests. Suddenly, a young doctor of medicine blurted out his low opinion of philosophy. “What’s the good of such clap-trap?” he asked. “Where does it get you?”

The great philosopher settled quietly back into his chair and smiled in appreciation of the young man’s frankness. “You want to know what’s the good of it all,” he said. “The good of it is that you climb mountains.”

“Climb mountains!” retorted the youth, unimpressed. “And what’s the use of doing that?”

“You see other mountains to climb,” was the reply. “You come down, climb the next mountain, and see still others to climb.” Then, putting his hand ever so gently on the young man’s knee, he said, “When you are no longer interested in climbing mountains to see other mountains to climb, life is over.”

— The Progressive (Madison, July 1952)