Get PeakVisor App

Sign In

Search by GPS coordinates

- Latitude

- ° ' ''

- Longitude

- ° ' ''

- Units of Length

Yes

Cancel

❤ Wishlist ×

Choose

Delete

Liberia is a nation straddling Africa’s west coast. Given its equatorial location, the country is characterized mainly by tropical vegetation and rainforest and is rich in natural resources and recreation. Liberia’s history is one of both pride and tumult. Having largely avoided colonization during the 19th century, the country was roiled by civil war from the late '80s until 2003. Since the peace accord, it has become one of the world’s last true adventure destinations; travel in Liberia is not necessarily straightforward, but it’s a nation unlike any other. There are 200 named mountains in Liberia. The highest and the most prominent mountain is Mount Wuteve (1,448 m / 4,750 ft). The slopes of Mount Nimba (1,752 m / 5,748 ft) are higher, but the actual summit is located on the borders of neighboring Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea.

Liberia is a relatively small country, covering an area of 111,369 ㎢ (43,000 square miles). It’s bordered by Sierra Leone to the northwest, Guinea to the north, Côte d'Ivoire to the east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the south and southwest. Liberia consists of three distinct regions: the coastal plain, the central plateau, and the mountainous highlands of the interior.

The coastal plain is a humid, low-lying region dotted with lagoons, mangrove swamps, and beaches, as well as some development, mainly in the form of small fishing villages. Liberia's capital, Monrovia, is one of the few West African capitals directly on the coast. The plain stretches for about 20-40 km inland.

The central plateau rises beyond, featuring equatorial forests and the nation’s most fertile agricultural land. The highlands of northwest Liberia include Mount Wuteve, Liberia’s tallest peak.

Liberia has six major rivers: St. Paul, St. John, Mano, Lofa, Cavalla, and Cestos. The heavy tropical wet season (May-October) often precipitates flooding along the riverine lowlands. Traveling around rural Liberia can be difficult during this time due to flooding and mud-covered, unpaved roads. At the same time, the dry season, featuring harmattan winds from the Sahara desert, has also become increasingly prolonged.

Demographically, Liberia has a population of about 5.5 million; nearly half the country is under the age of 15, and only 2.8% are over 65. Liberia remains one of the world’s poorest countries, with a GDP of about 4.3 billion USD.

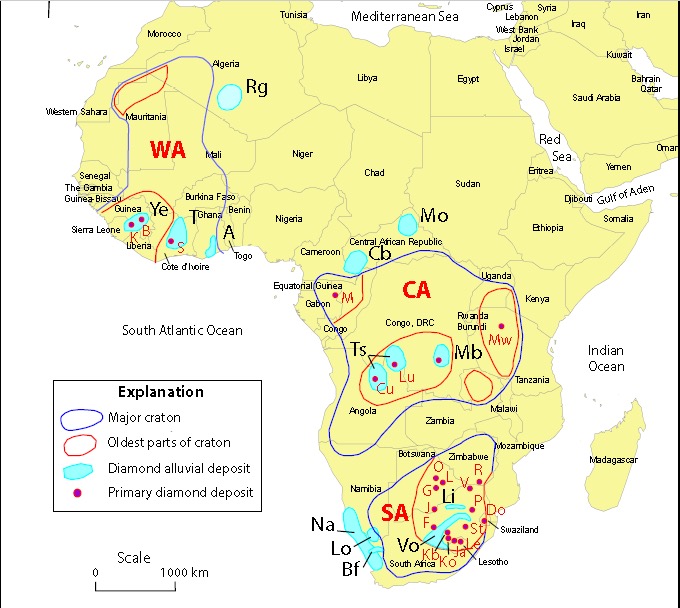

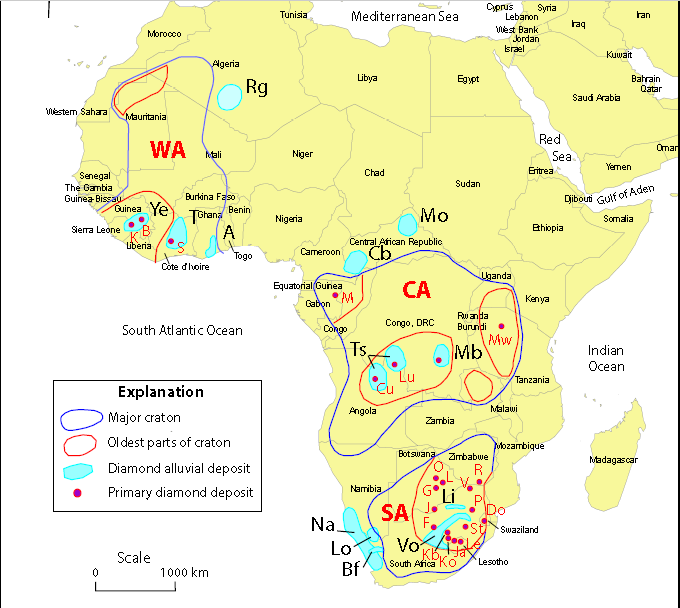

Geologically, Liberia is situated on the West African Craton. The country’s bedrock is primarily Precambrian, formed over 2 billion years ago.

The mountainous areas of interior Liberia are part of the Guinea Highlands, uplifted 30-50 million years ago. These mountains stretch from Côte d’Ivoire and through Liberia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and southwestern Mali.

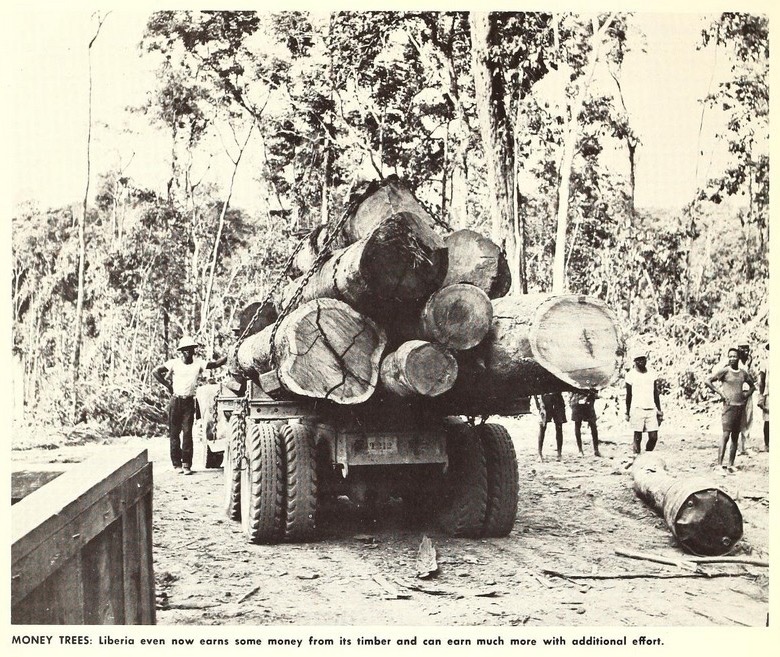

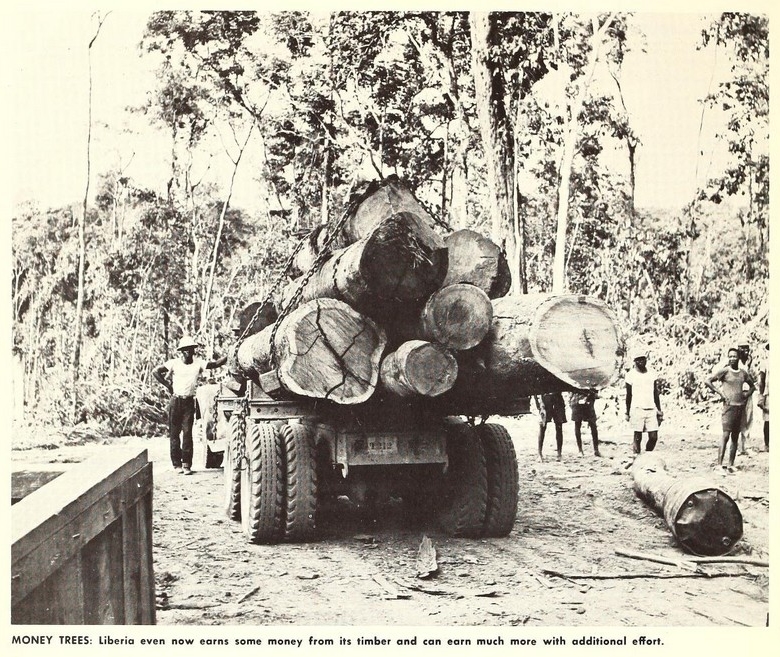

The iron ore deposits in Liberia are among the richest in the world. The country also possesses gold and bauxite deposits and renewable natural resources like timber. While Sierra Leone’s “blood diamonds” became a source of international outcry, rebel groups in Liberia illegally exported timber as a way to fund their operations. Conservation took a major hit during the decades of war; for example, at Sapo National Park, at least three staff were killed while many more became refugees. Most of the park’s infrastructure was destroyed, and protection for its wildlife was virtually nonexistent. Meanwhile, rebel groups harvested old-growth Guinean rainforest, further diminishing habitat.

Liberia also has diamond deposits, though not to the same extent as its neighbors. Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire all have kimberlite pipes—geological channels that funnel diamonds from deep within the Earth’s mantle—within their territories, as well as extensive alluvial (river sediment) circulation of the resulting diamonds.

Liberia’s ecology is defined by its proximity to the equator. About 40% of the land area is covered in rainforest, part of the Upper Guinean Forest, a global biodiversity hotspot. Liberia comprises 42% of the remaining Upper Guinean, the most of any country (Côte d’Ivoire is second at 28%). The towering trees (reaching 70 m (230 ft) in height) and thick undergrowth provide habitats for numerous animals and endangered species like the Western chimpanzee and the pygmy hippopotamus. As with all tropical forests, these tropics also act as significant carbon sinks and regulate the regional climate.

Liberia’s coastline stretches over 560 kilometers (350 miles). In addition to dense tropical jungles, Liberia’s coastal ecosystems feature beaches, mangrove forests, lagoons, and estuaries. Mangroves serve as fish nurseries and as a buffer for coastal erosion. Lagoons and estuaries are highly biologically productive ecosystems and especially critical for migratory birds. Much of the coastal population still derives its livelihood in the traditional fishing industry, where they use artisanal canoes up to depths of 20-40 meters (66-132 ft).

Liberia’s ecology faces significant threats from deforestation, mining, and agricultural expansion. Illegal logging and shifting cultivation have led to habitat loss. Iron ore, gold, and diamond extraction have caused soil degradation and pollution. Poaching and unsustainable hunting further threaten the country’s wildlife. In particular, the Liberian Civil Wars had a catastrophic impact on forests and wildlife conservation. Rebel factions logged rare old-growth tropical rainforests, exporting the timber for revenue to fuel the conflicts. Meanwhile, protection against poaching was essentially whittled down to nothing, with much of the infrastructure at the national parks destroyed and the staff killed for displaced.

Climate change will likely significantly impact Liberia, whose population is currently grossly underprepared for its impacts. In the coming decades, the country can expect heavier tropical deluges and more intense droughts during the Harmattan dry season, where dry winds blow from the Sahara desert. Much of Liberia’s population lives along the coastal plain, where sea level rise is poised to uproot the most low-lying and vulnerable of these communities.

Nowadays, although it’s still an uphill battle, an end to the Civil Wars has given conservation a boost in Liberia. The country now has four national parks, over a dozen national forests, and many smaller parks and protected entities. Sustainable land management practices and increased focus on ecotourism are slowly gaining momentum, offering hope for the preservation of Liberia’s ecology. This is immense progress, considering Liberia didn’t have a national park until 1983. Nevertheless, climate change and population growth—Liberia is one of the world’s fastest-growing populations—will put increasing pressure on ecological systems in the next few decades.

Sapo National Park in southeastern Liberia is the country’s largest protected area at 180,400 hectares (445,188 acres). The park is a critical part of the Upper Guinean Forest and is the second-largest single tract of forest after Taï National Park in neighboring Cote d’Ivoire. It was Liberia’s first park, formed in 1983, although the brutal series of Civil Wars thwarted conservation.

Most notably, the park is home to populations of the elusive pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis) and several species of duikers, which are small forest antelopes native to the Upper Guinean. Only 11% of the park’s land area is secondary forest; the vast majority is undisturbed, and some pockets have likely never been impacted by humans, one of the last forests remaining in this category globally.

Traveling around Liberia is never entirely straightforward, but Sapo is one of the country’s most visited attractions, so you’ll easily find transportation, accommodation, and other necessities.

The Gola Rainforest spans the border between Liberia and Sierra Leone; it’s part of the Lofa-Mano National Park on the Liberian Side since 2016 and Gola National Park on the Sierra Leone side since 2010 (both comprise the Gola Forest Transboundary Peace Park).

In Liberia, the Gola Forest covers an area of approximately 90,000 hectares (222,395 acres). Like Sapo National Park, it’s one of the largest remaining tracts of Upper Guinean Forest. Notably, the Sierra Leone side is much larger, encompassing 350,000 hectares. Some of the most charismatic residents include forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis, and the rare Gola malimbe (Malimbus ballmanni), an endemic bird species. The forest is home to 49 species of large mammals and an impressive 600 species of butterfly (nearly rivaling the 899 plant species).

The park is currently being considered for UNESCO World Heritage status.

Liberia’s human history began relatively recently by African standards. Africa is the cradle of civilization, where humanity evolved about 300,000 years ago. The great “out-of-Africa” migration dispersed people throughout the world. However, it’s likely that humans had already crossed the Bering Strait and scattered throughout the Americas before Liberia saw human settlement.

The intensity of Liberia’s dense tropical forest was nowhere near as conducive for modern humans as the open savannah of other parts of Africa. We don’t see traces of humans here until near the end of the Paleolithic period (~12,000 years ago). The rise of agriculture eventually promoted the settlement of more people in West Africa. The domestication of African rice in the Niger River Basin 3,000 years ago was particularly important (varieties of Asian rice eventually proved even more suited to the climate and are the primary type cultivated today). About 17 significant ethnic groups have come to inhabit Liberia, with the Kpelle being the most common (about 20% of Liberians).

In 1822, the American Colonization Society (ACS), an organization that sought to resettle free African Americans in Africa, founded modern Liberia. The freed settlers, known as Americo-Liberians, arrived intending to build a new society, drawing on their American experiences and institutions; Monrovia, named after U.S. President James Monroe, was their first settlement. Mortality from tropical disease was high, and the majority of these initial settlers eventually died.

Americo-Liberians declared Liberia an independent nation in 1847, making it the first African republic to achieve independence, and established a government modeled after the United States. The country is one of two in Africa to have never technically been colonized, the other being Ethiopia. However, the Americo-Liberians formed a separate ethnic identity from the native Liberians and coalesced into a ruling upper class. The U.S. government also propped up their regime for decades before achieving independence. While the level of Western colonization and exploitation was nowhere near as severe as in other African nations, exploitation by Americo-Liberians ultimately formed the same class structure that has precipitated post-colonial wars throughout Africa.

The foundation of Liberia was not without conflict. As mentioned, the Americo-Liberians controlled the government and the economy and often marginalized the indigenous African communities. Although Liberia was promoted as a place of freedom for the settlers, the emerging social hierarchy created deep divisions.

Liberia’s status as an independent republic allowed it to maintain ties with the United States. The American Firestone Rubber Company established vast plantations in the 1920s, for example. Liberia’s small Americo-Liberian elite benefitted from these economic ties, but much of the wealth remained concentrated at the top. Political power was centralized in Monrovia, with little investment in rural areas where the majority of the indigenous population lived.

In 1980, long-standing tensions erupted in a violent coup. Samuel Doe, an indigenous Liberian, overthrew the Americo-Liberian-led government, marking the first time indigenous Liberians took control of the state. Unfortunately, Doe’s rule was authoritarian and rife with human rights abuse and only furthered divisions. In 1989, Liberia descended into civil war as rebel groups rose against Doe’s government. The ensuing conflict led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people and the collapse of Liberia’s already-modest economy and infrastructure. In fact, over 70% of physical infrastructure was destroyed in the 14 years of war.

The civil war lasted until 2003 when the U.N. helped to broker peace. In 2005, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was elected president, becoming Africa’s first female head of state. The country made some progress in stabilizing the political landscape and rebuilding infrastructure, with improvements in education and healthcare. Liberia’s life expectancy is about 61 years, up from 43 years in the ‘90s.

Nevertheless, Liberia continues to face headwinds. Liberia is one of the world’s poorest countries, with much of the population subsisting on less than 2 dollars a day. Endemic corruption exists at every level of the government. Most people don’t use contraceptives, and birth rates are high, above four children per woman. HIV infection hovers around 2 % of the population. The Ebola outbreak in 2014 further strained the nation.

Despite Liberia’s challenges, you won’t meet more welcoming and upbeat people. Liberians are known for their warmth and hospitality; family and community play central roles in daily life, and both urban and rural Liberians have close-knit social networks.

Traveling anywhere presents challenges, but Liberia is on another level. It’s hard to arrive with an itinerary and complete everything on schedule. This is Africa, and things don’t always go as planned.

Getting around the country is one of the biggest challenges. You’re unlikely to find anything resembling smooth or paved outside the main roads. Flooding and mud are consistent during the wet season, and it’s hard to deal with daily torrential rains. Therefore, you should probably visit during the dry season, which coincides with the North American winter. However, no matter when you visit, prepare for rain. These are the tropics, after all.

Only 4x4 rentals will cut it in Liberia due to the conditions of the roads. Still, breakdowns and mechanical casualties are to be expected. Bush taxis are the best way to get to and fro the smaller villages if you don’t have a car. Motorcycle taxis service places that are too rural for even bush taxis (bring your own helmet).

One advantage in Liberia is that English is the official language. Not everyone speaks English, but you’ll get by. For maximum tourist cred, learn a few phrases in the local language as a sign of respect.

Liberia is off the beaten path, both figuratively and, when hiking, literally. There isn’t much established hiking in the country because the jungle simply devours any sort of trail, even on a day-to-day basis. If you’re the first one down a stretch of trail, you’ll have all kinds of spiderwebs and residue from the night before piling up on your body. Established trails can disappear in the course of a single wet season. Even the roads between villages are like glorified double tracks, as the jungle constantly bears down.

One idea is to walk or ride your bike along the network of dirt roads, which will offer an experience not dissimilar from a wilderness trail, depending on the locale. Any village will have local farm trails heading to and fro through the forest, but you’ll have to figure it out in person rather than on the Internet.

National Parks, like Sapo, have some trail networks as well.

Mountain Nimba is one of Liberia’s most popular hikes. It’s a gorgeous hike within a UNESCO World Heritage nature preserve located across Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Guinea. But it’s also one of the few places in the country conducive to hiking.

Here, grasslands rise from the surrounding jungle. It’s the only region in Liberia that harbors a tropical savannah climate classification. As a result, it’s a peaceful hike through alpine meadows with panoramic views rather than an arduous bushwack through thick jungle.

The park is about 30 km east of Gbarnga and is one of the most visited spots for international visitors.

The Kpatawee Waterfall is also located near Gbarnga, though it’s embedded deep in the lowland rainforest. It’s worth spending a day trekking out to the falls and going for a swim. You can also camp here, or stay at the ecolodge at the base.

Liberia is emerging as a top surf destination in Africa. The best waves are found around the Robertsport Peninsula, about four hours north along the coast from Monrovia. The best way to get here is to fly to Monrovia and take a bush taxi to Robertsport.

Since the end of the civil war, a steady trickle of foreign visitors and enthusiastic locals have cultivated a mini surf scene. Robertsport is now home to highly accomplished local surfers and even a surf school. You can rent a board at a couple of local shops; it may be too tricky to schlep one of your own out here. Fortunately, Liberia is so far off the beaten path that you won’t have much competition for waves.

The best time for big barrels is April to October, which, unfortunately for surfers, also coincides with the wet season. You can expect consistent swells but also consistent tropical deluges of rain, usually in the afternoon. The monthly rainfall is nearly a meter (40 inches) during July, August, and September. The dry season (North American winter) offers much better weather but far less reliable swells, although it can still be decent. Traveling to and from Robertsport in the wet season can be a tepid affair, so patience is important. Many parts of the country are unreachable if the roads are too muddy or flooded; however, Robertsport is close enough to the main urban center to have better infrastructure.

The coast here is predominately southwest and is known for lefty point breaks. Some of the best surf spots are Bernard Beach, Cassava, Coopers Beach, Cotton Trees, Dorothy’s, Homco Beach, Mamba Beach, and Tropicana. But don’t worry, you can easily hire a local to show you around when you arrive.

Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, is set against the shimmering Atlantic coastline. The city was founded in 1822 by free African Americans and is named after U.S. President James Monroe, who supported their desire for resettlement in the motherland. With 1.7 million people, Monrovia is home to about ⅓ of the country’s population.

Liberia is the first African republic founded by repatriates (now known as Americo-Liberians), and Providence Island was where these settlers arrived. The National Museum of Liberia is worthy of a visit as it gives an overview of Liberia’s culture. You’ll see everything from traditional masks and crafts to historical photos.

The vast majority of Western travelers have never been to a place like Monrovia. The city is bustling with traffic, though mostly motorbikes and carts rather than cars. Many bikes are piled up with two or three people. The streets can be dangerous; vehicular accidents are one of the leading causes of premature deaths here. Yet Monrovia is bursting with life and energy. The roads and sidewalks hum with local markets, where vendors peddle fresh fish and handmade goods. The city’s food is a colorful mix of local Liberian flavors like spicy jollof rice, cassava leaves, and grilled fish, alongside international staples like pizza.

Silver Beach and CeCe Beach offer an escape from the urban jungle, with palm-lined shores and warm Atlantic waters. Expect the water to be around 28℃. It’s been over 20 years since the Second Civil War came to an end, and those decades have been spent rebuilding and revitalizing the spirits of Liberians, many of whom had suffered their entire lives through war and desperation.

Gbarnga (pop. 34,000) is located in central Liberia. You may pass through here if you head toward the Nimba Mountains. Gbarnga presents the more rural Liberia of the country’s heartland (although it’s still the nation’s 4th most populous city). It is home to Cuttington University, one of the country’s most respected institutions of higher learning. The town itself is surrounded by fertile farmland, where crops like cassava, rice, and palm oil are cultivated, making agriculture the backbone of the local economy. Gbarnga’s infrastructure is modest, with basic services and small businesses. Like other locales in West Africa, the streets are filled with motorbikes, small markets, and local vendors, though not to the same extent as Monrovia. Historically, Gbarnga was a base for various factions during Liberia’s civil wars, and the scars of that conflict are still visible.

Robertsport (pop. 4,000) is north of Monrovia on Liberia’s northwestern coast. Picturesque beaches stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, which abuts dense jungle. The town’s economy revolves around fishing, with local fishermen setting out daily; about 30-40% of villagers are employed in the industry. Robertsport has a colonial past with Antebellum South plantation-style architecture brought by early Americo-Liberian settlers (many of these early structures have been destroyed in the war or decayed into ruins). Nowadays, Robertsport is known for its surfing. There is even a small local African surf community and school after some visitors taught the villagers how to surf.

If you head into the Guinea Highlands of northeastern Liberia, you’ll likely pass through the town of Voinjama (pop. 26,000). Voinjama’s economy revolves around farming, with rice, cassava, and palm oil being the main crops grown in the surrounding area. Voinjama’s infrastructure is basic, with dirt roads and modest buildings. The surrounding countryside is full of dense jungle and hill country with exceptional biodiversity.

Explore Liberia Mountains with the PeakVisor 3D Map and identify its summits.